Creative Commons logo

A Creative Commons (CC) license is one of several public copyright licenses that enable the free distribution of an otherwise copyrighted "work".

A CC license is used when an author wants to give other people the

right to share, use, and build upon a work that they (the author) have

created. CC provides an author flexibility (for example, they might

choose to allow only non-commercial uses of a given work) and protects

the people who use or redistribute an author's work from concerns of

copyright infringement as long as they abide by the conditions that are

specified in the license by which the author distributes the work.

There are several types of Creative Commons licenses. The

licenses differ by several combinations that condition the terms of

distribution. They were initially released on December 16, 2002 by Creative Commons, a U.S. non-profit corporation founded in 2001. There have also been five versions of the suite of licenses, numbered 1.0 through 4.0. As of December 2018, the 4.0 license suite is the most current.

In October 2014, the Open Knowledge Foundation approved the Creative Commons CC BY, CC BY-SA and CC0 licenses as conformant with the "Open Definition" for content and data.

Applicable works

The second version of the Mayer and Bettle promotional animation explains what Creative Commons is

Work licensed under a Creative Commons license is governed by applicable copyright law.

This allows Creative Commons licenses to be applied to all work falling

under copyright, including: books, plays, movies, music, articles,

photographs, blogs, and websites.

While Software is also governed by copyright law and CC licenses are applicable, the Creative Commons recommends Free and open-source software software licenses instead of Creative Commons licenses. Outside the FOSS licensing use case for software there are several usage examples to utilize CC licenses to specify a "Freeware" license model; examples are The White Chamber, Mari0 or Assault Cube. Also the Free Software Foundation recommends the CC0 as the preferred method of releasing software into the public domain.

There are over 35,000 works that are available in hardcopy and

have a registered ISBN number. Creative Commons splits these works into

two categories, one of which encompasses self-published books.

However, application of a Creative Commons license may not modify the rights allowed by fair use or fair dealing or exert restrictions which violate copyright exceptions. Furthermore, Creative Commons licenses are non-exclusive and non-revocable. Any work or copies of the work obtained under a Creative Commons license may continue to be used under that license.

In the case of works protected by multiple Creative Commons licenses, the user may choose either.

Types of licenses

Creative commons license spectrum between public domain (top) and all rights reserved (bottom). Left side indicates the use-cases allowed, right side the license components. The dark green area indicates Free Cultural Works compatible licenses, the two green areas compatibility with the Remix culture.

CC license usage in 2014 (top and middle), "Free cultural works" compatible license usage 2010 to 2014 (bottom)

The CC licenses all grant the "baseline rights", such as the right to

distribute the copyrighted work worldwide, for non-commercial purposes

and without modification. The details of each of these licenses depend on the version, and comprises a selection out of four conditions:

Icon Right Description

Attribution (BY) Licensees may copy, distribute, display and perform the work and make derivative works and remixes based on it only if they give the author or licensor the credits (attribution) in the manner specified by these.

Share-alike (SA) Licensees may distribute derivative works only under a license identical ("not more restrictive") to the license that governs the original work. (See also copyleft.) Without share-alike, derivative works might be sublicensed with compatible but more restrictive license clauses, e.g. CC BY to CC BY-NC.)

Non-commercial (NC) Licensees may copy, distribute, display, and perform the work and make derivative works and remixes based on it only for non-commercial purposes.

No Derivative Works (ND) Licensees may copy, distribute, display and perform only verbatim copies of the work, not derivative works and remixes based on it.

The last two clauses are not free content licenses, according to definitions such as DFSG or the Free Software Foundation's standards, and cannot be used in contexts that require these freedoms, such as Wikipedia. For software, Creative Commons includes three free licenses created by other institutions: the BSD License, the GNU LGPL, and the GNU GPL.

Mixing and matching these conditions produces sixteen possible

combinations, of which eleven are valid Creative Commons licenses and

five are not. Of the five invalid combinations, four include both the

"nd" and "sa" clauses, which are mutually exclusive; and one includes

none of the clauses. Of the eleven valid combinations, the five that

lack the "by" clause have been retired because 98% of licensors

requested attribution, though they do remain available for reference on

the website. This leaves six regularly used licenses + the CC0 public domain waiver.

Version 4.0 and international use

The original non-localized Creative Commons licenses were written

with the U.S. legal system in mind; therefore, the wording may be

incompatible with local legislation in other jurisdictions,

rendering the licenses unenforceable there. To address this issue,

Creative Commons asked its affiliates to translate the various licenses

to reflect local laws in a process called "porting." As of July 2011, Creative Commons licenses have been ported to over 50 jurisdictions worldwide.

The latest version 4.0 of the Creative Commons licenses, released

on November 25, 2013, are generic licenses that are applicable to most

jurisdictions and do not usually require ports. No new ports have been implemented in version 4.0 of the license. Version 4.0 discourages using ported versions and instead acts as a single global license.

Rights

Attribution

Since

2004, all current licenses other than the CC0 variant require

attribution of the original author, as signified by the BY component (as

in the preposition "by"). The attribution must be given to "the best of [one's] ability using the information available". Generally this implies the following:

- Include any copyright notices (if applicable). If the work itself contains any copyright notices placed there by the copyright holder, those notices must be left intact, or reproduced in a way that is reasonable to the medium in which the work is being re-published.

- Cite the author's name, screen name, or user ID, etc. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice to link that name to the person's profile page, if such a page exists.

- Cite the work's title or name (if applicable), if such a thing exists. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice to link the name or title directly to the original work.

- Cite the specific CC license the work is under. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice if the license citation links to the license on the CC website.

- Mention if the work is a derivative work or adaptation. In addition to the above, one needs to identify that their work is a derivative work, e.g., "This is a Finnish translation of [original work] by [author]." or "Screenplay based on [original work] by [author]."

Non-commercial licenses

The "non-commercial" option included in some Creative Commons licenses is controversial in definition,

as it is sometimes unclear what can be considered a non-commercial

setting, and application, since its restrictions differ from the

principles of open content promoted by other permissive licenses. In 2014 Wikimedia Deutschland published a guide to using Creative Commons licenses as wiki pages for translations and as PDF.

Zero / public domain

CC zero waiver/license logo.

Creative Commons Public Domain Mark. Indicates works which have already fallen into (or were given to) the public domain.

Besides licenses, Creative Commons also offers through CC0 a way to release material worldwide into the public domain. CC0 is a legal tool for waiving as many rights as legally possible. Or, when not legally possible, CC0 acts as fallback as public domain equivalent license. Development of CC0 began in 2007 and was released in 2009. A major target of the license was the scientific data community.

In 2010, Creative Commons announced its Public Domain Mark,

a tool for labeling works already in the public domain. Together, CC0

and the Public Domain Mark replace the Public Domain Dedication and

Certification, which took a U.S.-centric approach and co-mingled distinct operations.

In 2011, the Free Software Foundation added CC0 to its free software licenses, and currently recommends CC0 as the preferred method of releasing software into the public domain.

In February 2012 CC0 was submitted to Open Source Initiative (OSI) for their approval.

However, controversy arose over its clause which excluded from the

scope of the license any relevant patents held by the copyright holder.

This clause was added with scientific data in mind rather than software,

but some members of the OSI believed it could weaken users' defenses

against software patents. As a result, Creative Commons withdrew their submission, and the license is not currently approved by the OSI.

In 2013, Unsplash began using the CC0 license to distribute free stock photography. It now distributes several million photos a month and has inspired a host of similar sites, including CC0 photography companies and CC0 blogging companies. Lawrence Lessig, the founder of Creative Commons, has contributed to the site.

Unsplash moved from using the CC0 licence to their own similar licence

in June 2017, but with a restriction added on using the photos to make a

competing service which makes it incompatible with the CC0 licence.

In October 2014 the Open Knowledge Foundation

approved the Creative Commons CC0 as conformant with the "Open

Definition" and recommend the license to dedicate content to the public

domain.

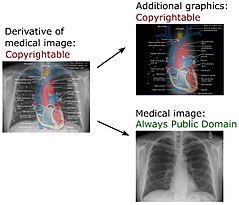

Adaptation

An example of a permitted combination of two works, one being CC BY-SA and the other being Public Domain.

Rights in an adaptation can be expressed by a CC license that is

compatible with the status or licensing of the original work or works on

which the adaptation is based.

Legal aspects

The

legal implications of large numbers of works having Creative Commons

licensing are difficult to predict, and there is speculation that media

creators often lack insight to be able to choose the license which best

meets their intent in applying it.

Some works licensed using Creative Commons licenses have been involved in several court cases.

Creative Commons itself was not a party to any of these cases; they

only involved licensors or licensees of Creative Commons licenses. When

the cases went as far as decisions by judges (that is, they were not

dismissed for lack of jurisdiction or were not settled privately out of

court), they have all validated the legal robustness of Creative Commons

public licenses. Here are some notable cases:

Dutch tabloid

In early 2006, podcaster Adam Curry

sued a Dutch tabloid who published photos from Curry's Flickr page

without Curry's permission. The photos were licensed under the Creative

Commons Non-Commercial license. While the verdict was in favor of Curry,

the tabloid avoided having to pay restitution to him as long as they

did not repeat the offense. Professor Bernt Hugenholtz, main creator of

the Dutch CC license and director of the Institute for Information Law

of the University of Amsterdam, commented, "The Dutch Court's decision

is especially noteworthy because it confirms that the conditions of a

Creative Commons license automatically apply to the content licensed

under it, and binds users of such content even without expressly

agreeing to, or having knowledge of, the conditions of the license."

Virgin Mobile

In 2007, Virgin Mobile Australia

launched an advertising campaign promoting their cellphone text

messaging service using the work of amateur photographers who uploaded

their work to Flickr

using a Creative Commons-BY (Attribution) license. Users licensing

their images this way freed their work for use by any other entity, as

long as the original creator was attributed credit, without any other

compensation required. Virgin upheld this single restriction by printing

a URL leading to the photographer's Flickr page on each of their ads.

However, one picture, depicting 15-year-old Alison Chang at a

fund-raising carwash for her church,

caused some controversy when she sued Virgin Mobile. The photo was

taken by Alison's church youth counselor, Justin Ho-Wee Wong, who

uploaded the image to Flickr under the Creative Commons license. In 2008, the case (concerning personality rights rather than copyright as such) was thrown out of a Texas court for lack of jurisdiction.

SGAE vs Fernández

In the fall of 2006, the collecting society Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE) in Spain sued Ricardo Andrés Utrera Fernández, owner of a disco bar located in Badajoz

who played CC-licensed music. SGAE argued that Fernández should pay

royalties for public performance of the music between November 2002 and

August 2005. The Lower Court rejected the collecting society's claims

because the owner of the bar proved that the music he was using was not

managed by the society.

In February 2006, the Cultural Association Ladinamo (based in Madrid, and represented by Javier de la Cueva)

was granted the use of copyleft music in their public activities. The

sentence said: "Admitting the existence of music equipment, a joint

evaluation of the evidence practiced, this court is convinced that the

defendant prevents communication of works whose management is entrusted

to the plaintiff [SGAE], using a repertoire of authors who have not

assigned the exploitation of their rights to the SGAE, having at its

disposal a database for that purpose and so it is manifested both by the

legal representative of the Association and by Manuela Villa Acosta, in

charge of the cultural programming of the association, which is

compatible with the alternative character of the Association and its

integration in the movement called 'copy left'".

GateHouse Media, Inc. v. That's Great News, LLC

On June 30, 2010 GateHouse Media filed a lawsuit against That's Great News. GateHouse Media owns a number of local newspapers, including Rockford Register Star,

which is based in Rockford, Illinois. That's Great News makes plaques

out of newspaper articles and sells them to the people featured in the

articles.

GateHouse sued That's Great News for copyright infringement and breach

of contract. GateHouse claimed that TGN violated the non-commercial and

no-derivative works restrictions on GateHouse Creative Commons licensed

work when TGN published the material on its website. The case was

settled on August 17, 2010, though the settlement was not made public.

Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group, LLC

The

plaintiff was photographer Art Drauglis, who uploaded several pictures

to the photo-sharing website Flickr using Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License (CC BY-SA), including one

entitled "Swain's Lock, Montgomery Co., MD.". The defendant was Kappa

Map Group, a map-making company, which downloaded the image and used it

in a compilation entitled "Montgomery Co. Maryland Street Atlas". Though

there was nothing on the cover that indicated the origin of the

picture, the text "Photo: Swain's Lock, Montgomery Co., MD Photographer: Carly Lesser & Art Drauglis, Creative Commoms [sic], CC-BY-SA-2.0" appeared at the bottom of the back cover.

The validity of the CC BY-SA 2.0 as a license was not in dispute.

The CC BY-SA 2.0 requires that the licensee to use nothing less

restrictive than the CC BY-SA 2.0 terms. The atlas was sold commercially

and not for free reuse by others. The dispute was whether Drauglis'

license terms that would apply to "derivative works" applied to the

entire atlas. Drauglis sued the defendants in June 2014 for copyright

infringement and license breach, seeking declaratory and injunctive

relief, damages, fees, and costs. Drauglis asserted, among other things,

that Kappa Map Group "exceeded the scope of the License because

defendant did not publish the Atlas under a license with the same or

similar terms as those under which the Photograph was originally

licensed." The judge dismissed the case on that count, ruling that the atlas was not a derivative work of the photograph in the sense of the license, but rather a collective work.

Since the atlas was not a derivative work of the photograph, Kappa Map

Group did not need to license the entire atlas under the CC BY-SA 2.0

license. The judge also determined that the work had been properly

attributed.

In particular, the judge determined that it was sufficient to

credit the author of the photo as prominently as authors of similar

authorship (such as the authors of individual maps contained in the

book) and that the name "CC-BY-SA-2.0" is sufficiently precise to locate

the correct license on the internet and can be considered a valid URI

of the license.

Verband zum Schutz geistigen Eigentums im Internet (VGSE)

This

incident has not been tested in court, but it highlights a potentially

disturbing practice. In July 2016, German computer magazine LinuxUser reports that a German blogger Christoph Langner used two CC-BY licensed photographs from Berlin photographer Dennis Skley on his private blog Linuxundich.de. Langner duly mentioned the author and the license and added a link to the original. Langner was later contacted by the Verband zum Schutz geistigen Eigentums im Internet

(VGSE) (Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property in the

Internet) with a demand for €2300 for failing to provide the full name

of the work, the full name of the author, the license text, and a source

link, as is apparently required by the fine print in the license. Of

this sum, €40 goes to the photographer, and the remainder is retained by

VGSE.

Works with a Creative Commons license

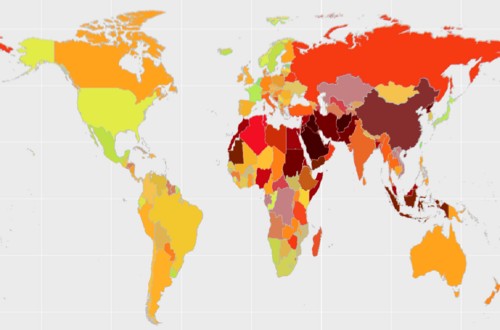

Number of Creative Commons licensed works as of 2017, per State of the Commons report

Creative Commons maintains a content directory wiki of organizations and projects using Creative Commons licenses. On its website CC also provides case studies of projects using CC licenses across the world. CC licensed content can also be accessed through a number of content directories and search engines.

Retired licenses

Due to either disuse or criticism, a number of previously offered Creative Commons licenses have since been retired,

and are no longer recommended for new works. The retired licenses

include all licenses lacking the Attribution element other than CC0, as

well as the following four licenses:

- Developing Nations License: a license which only applies to developing countries deemed to be "non-high-income economies" by the World Bank. Full copyright restrictions apply to people in other countries.

- Sampling: parts of the work can be used for any purpose other than advertising, but the whole work cannot be copied or modified

- Sampling Plus: parts of the work can be copied and modified for any purpose other than advertising, and the entire work can be copied for noncommercial purposes

- NonCommercial Sampling Plus: the whole work or parts of the work can be copied and modified for non-commercial purposes