With the 42nd Amendment of the Constitution of India enacted in 1976, the Preamble to the Constitution asserted that India is a secular nation. institutions to recognise and accept all religions, enforce parliamentary laws instead of religious laws, and respect pluralism. India does not have an official state religion. In matters of law in modern India, however, the applicable code of law is unequal, and India's personal laws - on matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, alimony - varies with an individual's religion. Muslim Indians have Sharia-based Muslim Personal Law, while Hindu, Christian and Sikh Indians live under common law. It is further complicated by the fact that many Hindu temples of great religious significance are administered and managed by the Indian government. The attempt to respect unequal, religious law has created a number of issues in India such as acceptability of child marriage, polygamy, unequal inheritance rights, extra judicial unilateral divorce rights favorable to some males, and conflicting interpretations of religious books.

Secularism as practiced in India, with its marked differences with Western practice of secularism, is a controversial topic in India. See also pseudo-secularism Supporters of the Indian concept of secularism claim it respects. Supporters of this form of secularism claim that any attempt to introduce a uniform civil code, that is equal laws for every citizen irrespective of his or her religion, would impose majoritarian Hindu sensibilities and ideals. Opponents argue that India's acceptance of Sharia and religious laws violates the principle of Equality before the law.

Secularism is a politically charged topic in India and often divides political factions. While there are many secular political parties which enjoy widespread support especially in Kerala, there are also parties that advocate the idea of India as a country for only one religious community. Complaints have been raised from different factions that secularism has been selectively applied in policy to suppress opposing religious views.

History

Indian religions are known to have co-existed and evolved together for many centuries before the arrival of Islam in the 12th century, followed by Mughal and colonial

era. To understand how, it is necessary to have an insight into how the

concept of secularism grew in India. The religion, practices and

beliefs of the Indus Valley Civilization

has received considerable attention from the view of identifying the

precursor of later Indian dharmic religions. There existed worship of

the great male god and a mother goddess; deification and veneration of

animals and plants; and the worship of many symbolic representations of

the world around. Consequently, religion was very accomodative and

without a rigid structure; it was polytheistic as well as agnostic,

henotheistic as well as panentheistic at the same time. This tolerance

towards and acceptance of other religious beliefs persisted in the dharmic religions

that followed. Hence the dharmic religions lack a proselytism

tradition. There is no belief in the superiority of their god. Quite

conversely, there are instances in religious texts like the Ramayana and

the Mahabharatha, wherein even the antagonist on the side of adharma

are shown to have a admirable traits, while Gods on the side of dharma

are shown as having fallacies. This encouraged a unique outlook of

questioning, open-mindness and acceptance in Indian religions.

Ellora caves,

a world heritage site, are in the Indian state of Maharashtra. The 35

caves were carved into the vertical face of the Charanandri hills

between the 5th and 10th centuries. The 12 Buddhist caves, 17 Hindu

caves and 5 Jain caves, built in proximity, suggest religious

co-existence and secular sentiments for diversity prevalent during

pre-Islamic period of Indian history.

Ashoka about 2200 years ago, Harsha about 1400 years ago accepted and patronised different religions.

The people in ancient India had freedom of religion, and the state

granted citizenship to each individual regardless of whether someone's

religion was Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism or any other. Ellora cave

temples built next to each other between 5th and 10th centuries, for

example, shows a coexistence of religions and a spirit of acceptance of

different faiths.

There should not be honour of one’s own (religious) sect and condemnation of others without any grounds.

— Ashoka, Rock Edicts XII, about 250 BC

This approach to interfaith relations changed with the arrival of

Islam and establishment of Delhi Sultanate in North India by the 12th

century, followed by Deccan Sultanate in Central India.

The political doctrines of Islam, as well as its religious views were

at odds with doctrines of Hinduism, Buddhism and other Indian religions.

New temples and monasteries were not allowed. As with Levant, Southeast

Europe and Spain, Islamic rulers in India treated Hindus as dhimmis in exchange of annual payment of jizya

taxes, in a sharia-based state jurisprudence. With the arrival of

Mughal era, Sharia was imposed with continued zeal, with Akbar - the

Mughal Emperor - as the first significant exception.

Akbar sought to fuse ideas, professed equality between Islam and other

religions of India, forbade forced conversions to Islam, abolished

religion-based discriminatory jizya taxes, and welcomed building of

Hindu temples. However, the descendants of Akbar, particularly Aurangzeb,

reverted to treating Islam as the primary state religion, destruction

of temples, and reimposed religion-based discriminatory jizya taxes.

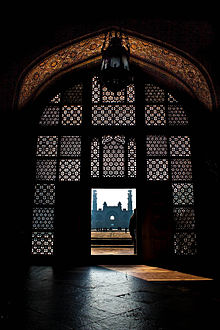

Akbar's tomb

at Sikandra, near Agra India. Akbar's instruction for his mausoleum was

that it incorporate elements from different religions including Islam

and Hinduism.

After Aurangzeb, India came into control of East India Company and the British Raj.

The colonial administrators did not separate religion from state, but

marked the end of unequal hierarchy between Islam and Hinduism, and

reintroduced the notion of equality before the law for Hindus,

Christians and Muslims. The British Empire sought commerce and trade, with a policy of neutrality to all of India's diverse religions.

Before 1858, the Britishers followed the policy of patronizing and

supporting the native religions as the earlier rulers had done.

By the mid-19th century, the British Raj administered India, in

matters related to marriage, inheritance of property and divorces,

according to personal laws based on each Indian subject's religion,

according to interpretations of respective religious documents by

Islamic jurists, Hindu pundits and other religious scholars. In 1864,

the Raj eliminated all religious jurists, pandits and scholars because

the interpretations of the same verse or religious document varied, the

scholars and jurists disagreed with each other, and the process of

justice had become inconsistent and suspiciously corrupt.

The late 19th century marked the arrival of Anglo-Hindu and

Anglo-Muslim personal laws, where the governance did not separate the

state and religion, but continued to differentiate and administer people

based on their personal religion.

The British Raj provided the Indian Christians, Indian Zoroastrians and

others with their own personal laws, such as the Indian Succession Act

of 1850, Special Marriage Act of 1872 and other laws that were similar

to Common Laws in Europe.

| “ | For several years past it has been the cherished desire of the Muslims of British India that Customary Law should in no case take the place of Muslim Personal Law. The matter has been repeatedly agitated in the press as well as on the platform. The Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind, the greatest Moslem religious body has supported the demand and invited the attention of all concerned to the urgent necessity of introducing a measure to this effect. | ” |

| — Preamble to Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, | ||

Although the British administration provided India with a common law,

it's divide and rule policy contributed to promoting discord between

communities. The Morley-Minto reforms provided separate electorate to Muslims, justifying the demands of the Muslim league.

In the first half of 20th century, the British Raj faced

increasing amounts of social activism for self-rule by a disparate

groups such as those led by Hindu Gandhi and Muslim Jinnah; the colonial

administration, under pressure, enacted a number of laws before India's

independence in 1947, that continue to be the laws of India in 2013.

One such law enacted during the colonial era was the 1937 Indian Muslim

Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, which instead of separating state and religion for Western secularism, did the reverse.

It, along with additional laws such as Dissolution of Muslim

Marriages Act of 1939 that followed, established the principle that

religious laws of Indian Muslims can be their personal laws. It also set

the precedent that religious law, such as sharia, can overlap and

supersede common and civil laws,

that elected legislators may not revise or enact laws that supersede

religious laws, that people of one nation need not live under the same

laws, and that law enforcement process for different individuals shall

depend on their religion. The Indian Muslim Personal Law (Shariat)

Application Act of 1937 continues to be the law of land of modern India

for Indian Muslims, while parliament-based, non-religious uniform civil

code passed in mid-1950s applies to Indians who are Hindus (which

includes Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs, Parsees), as well as to Indian

Christians and Jews.

Current status

The

7th schedule of Indian constitution places religious institutions,

charities and trusts into so-called Concurrent List, which means that

both the central government of India, and various state governments in

India can make their own laws about religious institutions, charities

and trusts. If there is a conflict between central government enacted

law and state government law, then the central government law prevails.

This principle of overlap, rather than separation of religion and state

in India was further recognised in a series of constitutional amendments

starting with Article 290 in 1956, to the addition of word ‘secular’ to

the Preamble of Indian Constitution in 1975.

Buddhist monks at the Sera Monastery during a festival. The monastery was granted asylum by India and relocated to Mysore after the Chinese invasion of Tibet.

The overlap of religion and state, through Concurrent List structure,

has given various religions in India, state support to religious

schools and personal laws. This state intervention while resonant with

the dictates of each religion, are unequal and conflicting. For example,

a 1951 Religious and Charitable Endowment Indian law allows state

governments to forcibly take over, own and operate Hindu temples,

and collect revenue from offerings and redistribute that revenue to any

non-temple purposes including maintenance of religious institutions

opposed to the temple;

Indian law also allows Islamic religious schools to receive partial

financial support from state and central government of India, to offer

religious indoctrination, if the school agrees that the student has an

option to opt out from religious indoctrination if he or she so asks,

and that the school will not discriminate any student based on religion,

race or other grounds. Educational institutions wholly owned and

operated by government may not impart religious indoctrination, but

religious sects and endowments may open their own school, impart

religious indoctrination and have a right to partial state financial

assistance.

In matters of personal law, such as acceptable age of marriage

for girls, female circumcision, polygamy, divorce and inheritance,

Indian law permits each religious group to implement their religious law

if the religion so dictates, otherwise the state laws apply. In terms

of religions of India with significant populations, only Islam has

religious laws in form of sharia which India allows as Muslim Personal

Law.

Secularism in India, thus, does not mean separation of religion

from state. Instead, secularism in India means a state that is neutral

to all religious groups. Religious laws in personal domain, particularly

for Muslim Indians, supersede parliamentary laws in India; and

currently, in some situations such as religious indoctrination schools

the state partially finances certain religious schools. These

differences have led a number of scholars to declare that India is not a secular state, as the word secularism

is widely understood in the West and elsewhere; rather it is a strategy

for political goals in a nation with a complex history, and one that

achieves the opposite of its stated intentions.

Comparison with Western secularism

In

the West, the word secular implies three things: freedom of religion,

equal citizenship to each citizen regardless of his or her religion, and

the separation of religion and state.

One of the core principles in the constitution of Western democracies

has been this separation, with the state asserting its political

authority in matters of law, while accepting every individual's right to

pursue his or her own religion and the right of religion to shape its

own concepts of spirituality. Everyone is equal under law, and subject

to the same laws irrespective of his or her religion, in the West.

In contrast, in India, the word secular does not imply separation

of religion and state. It means equal treatment of all religions.

Religion in India continues to assert its political authority in

matters of personal law. The applicable personal law differ if an

individual's religion is Christianity, or Hindu.

The term secularism in India also differs from the French concept for

secularity, namely laïcité.

While the French concept demands absence of governmental institutions

in religion, as well as absence of religion in governmental institutions

and schools; the Indian concept, in contrast, provides financial

support to religious schools and accepts religious law over governmental

institutions. The Indian structure has created incentives for various

religious denominations to start and maintain schools, impart religious

education, and receive partial but significant financial support from

the Indian government. Similarly, Indian government financially

supports, regulates and administers the historic Hindu temples, Buddhist

monasteries, and certain Christian religious institutions; this direct

Indian government involvement in various religions is markedly different

from Western secularism.

Issues

Indian

concept of secularism, where religious laws supersede state laws and the

state is expected to even-handedly involve itself in religion, is a

controversial subject.

Any attempts and demand by the Indian populace to a uniform civil code

is considered a threat to right to religious personal laws by Indian

Muslims.

Shah Bano case

In 1978, the Shah Bano case brought the secularism debate along with a demand for uniform civil code in India to the forefront.

Shah Bano was a 62-year-old Muslim Indian who was divorced by her

husband of 44 years in 1978. Indian Muslim Personal Law required her

husband to pay no alimony. Shah Bano sued for regular maintenance

payments under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1978.

Shah Bano won her case, as well appeals to the highest court. Along

with alimony, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India wrote in

his opinion just how unfairly Islamic personal laws treated women and

thus how necessary it was for the nation to adopt a Uniform Civil Code.

The Chief Justice further ruled that no authoritative text of Islam

forbade the payment of regular maintenance to ex-wives.

The Shah Bano ruling immediately triggered a controversy and mass

demonstrations by Muslim men. The Islamic Clergy and the Muslim

Personal Law Board of India, argued against the ruling. Shortly after the Supreme Court's ruling, the Indian government with Rajiv Gandhi as Prime Minister,

enacted a new law which deprived all Muslim women, and only Muslim

women, of the right of maintenance guaranteed to women of Hindu,

Christian, Parsees, Jews and other religions. Indian Muslims consider

the new 1986 law, which selectively exempts them from maintenance

payment to ex-wife because of their religion, as secular because it

respects Muslim men's religious rights and recognises that they are

culturally different from Indian men and women of other religions.

Muslim opponents argue that any attempt to introduce Uniform Civil Code,

that is equal laws for every human being independent of his or her

religion, would reflect majoritarian Hindu sensibilities and ideals.

Islamic feminists

The controversy is not limited to Hindu versus Muslim populations in India. The Islamic feminists movement in India, for example, claim

that the issue with Muslim Personal Law in India is a historic and

ongoing misinterpretation of the Quran. The feminists claim that the

Quran grants Muslim women rights that in practice are routinely denied

to them by male Muslim ulema

in India. They claim that the ‘patriarchal’ interpretations of the

Quran on the illiterate Muslim Indian masses is abusive, and they demand

that they have a right to read the Quran for themselves and interpret

it in a woman-friendly way. India has no legal mechanism to accept or enforce the demands of these Islamic feminists over religious law.

Women’s rights in India

Some

religious rights granted by Indian concept of secularism, which are

claimed as abusive against Indian women, include child marriage,

polygamy, unequal inheritance rights of women and men, extrajudicial

unilateral divorce rights of Muslim man that are not allowed to a Muslim

woman, and subjective nature of shariat courts, ‘‘jamaats’’, ‘‘dar-ul

quzat’’ and religious qazis who preside over Islamic family law matters.

Goa

Goa is the only state in India which has Uniform Civil Code.The Goa Civil Code,

also called the Goa Family Law, is the set of civil laws that governs

the residents of the Indian state of Goa. In India, as a whole, there

are religion-specific civil codes that separately govern adherents of

different religions. Goa is an exception to that rule, in that a single

secular code/law governs all Goans, irrespective of religion, ethnicity

or linguistic affiliation.

Article 25(2)(b)

Article

25(2)(b) of the Indian constitution clubs Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains

along with Hindus, a position contested by some of these community

leaders.

Views

A

Hindu temple in Jaipur, India merging the traditional tiered tower of

Hinduism, the pyramid stupa of Buddhism and the dome of Islam. The

marble sides are carved with figures of Hindu deities, as well as

Christian Saints and Jesus Christ.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Sadanand Dhume

criticises Indian "Secularism" as a fraud and a failure, since it isn't

really "secularism" as it is understood in the western world (as separation of religion and state) but more along the lines of religious appeasement. He writes that the flawed understanding of secularism among India's left wing intelligentsia has led Indian politicians to pander to religious leaders and preachers including Zakir Naik, and has led India to take a soft stand against Islamic terrorism, religious militancy and communal disharmony in general.

Historian Ronald Inden writes:

| “ | Nehru's India was supposed to be committed to 'secularism'. The idea here in its weaker publicly reiterated form was that the government would not interfere in 'personal' religious matters and would create circumstances in which people of all religions could live in harmony. The idea in its stronger, unofficially stated form was that in order to modernise, India would have to set aside centuries of traditional religious ignorance and superstition and eventually eliminate Hinduism and Islam from people's lives altogether. After Independence, governments implemented secularism mostly by refusing to recognise the religious pasts of Indian nationalism, whether Hindu or Muslim, and at the same time (inconsistently) by retaining Muslim 'personal law' . | ” |

Amartya Sen, the Indian Nobel Laureate, suggests

that secularism in the political – as opposed to ecclesiastical – sense

requires the separation of the state from any particular religious

order. This, claims Sen, can be interpreted in at least two different

ways: The first view argues the state be equidistant from all religions –

refusing to take sides and having a neutral attitude towards them. The

second view insists that the state must not have any relation at all

with any religion. In both interpretations, secularism goes against

giving any religion a privileged position in the activities of the

state. Sen argues that the first form is more suited to India, where

there is no demand that the state stay clear of any association with any

religious matter whatsoever. Rather what is needed is to make sure that

in so far as the state has to deal with different religions and members

of different religious communities, there must be a basic symmetry of

treatment. Sen does not claim that modern India is symmetric in its

treatment or offer any views of whether acceptance of sharia

in matters such as child marriage is equivalent to having a neutral

attitude towards a religion. Critics of Sen claim that secularism as

practised in India is not the secularism of first or second variety Sen

enumerates.

Author Taslima Nasreen

sees Indian secularists as pseudo secularist, accusing them of being

biased towards Muslims saying, "Most secular people are pro-Muslims and

anti-Hindu. They protest against the acts of Hindu fundamentalists and

defend the heinous acts of Muslim fundamentalists". She also said that

most Indian politicians appease Muslims which leads to anger among

Hindus.

Pakistani columnist Farman Nawaz in his article "Why Indian Muslim Ullema are not popular in Pakistan?" states "Maulana Arshad Madani stated that seventy years ago the cause of division of India was sectarianism

and if today again the same temptation will raise its head then results

will be the same. Maulana Arshad Madani considers secularism inevitable

for the unity of India". Maulana Arshad Madani is a stanch critic of

sectarianism in India. He is of the opinion that India was divided in

1947 because of sectarianism. He suggests secularism inevitable for the solidarity and integrity of India.