https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrimination_against_people_with_HIV/AIDS

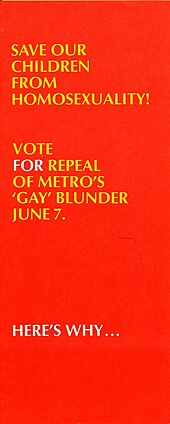

Discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS or serophobia is the prejudice, fear, rejection and discrimination against people afflicted with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV; people living with HIV/AIDS). Discrimination is one manifestation of stigma, and stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors may fall under the rubric of discrimination depending on the legislation of a particular country. HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. If left untreated, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). HIV/AIDS is a sexually transmitted disease and cannot be cured, but with proper treatment, the individual can live just as long as without the disease.

HIV/AIDS discrimination exists around the world, including ostracism, rejection, discrimination, and avoidance. Consequences of stigma and discrimination against PLHIV may result in low turn-out for HIV counselling and testing, identity crises, isolation, loneliness, low self-esteem and lack of interest in containing the disease.

Much HIV/AIDS stigma or discrimination involves homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, sex workers, and intravenous drug use.

In many developed countries, a strong correlation exists between HIV/AIDS and male homosexuality or bisexuality (the CDC states, "Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) represent approximately 2% of the United States population, yet are the population most severely affected by HIV"), and association is correlated with higher levels of sexual prejudice such as homophobic attitudes. An early name for AIDS was gay-related immune deficiency or GRID. During the early 1980s, HIV/AIDS was "a disorder that appears to affect primarily male homosexuals".

Some forms of serious discrimination can include: being excluded from consideration for a job, being prohibited from buying a house, needing to pay extra money when renting housing, compulsory HIV testing without prior consent or protection of confidentiality; the quarantine of HIV infected individuals and, in some cases, the loss of property rights when a spouse dies. HIV testing without permission or security may also be considered as wrongdoings against those with HIV. The United States' disability laws prohibit HIV/AIDS discrimination in housing, employment, education, and access to health and social services. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity enforces laws prohibiting housing discrimination based on actual or perceived HIV/AIDS status.

Discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS or serophobia is the prejudice, fear, rejection and discrimination against people afflicted with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV; people living with HIV/AIDS). Discrimination is one manifestation of stigma, and stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors may fall under the rubric of discrimination depending on the legislation of a particular country. HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. If left untreated, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). HIV/AIDS is a sexually transmitted disease and cannot be cured, but with proper treatment, the individual can live just as long as without the disease.

HIV/AIDS discrimination exists around the world, including ostracism, rejection, discrimination, and avoidance. Consequences of stigma and discrimination against PLHIV may result in low turn-out for HIV counselling and testing, identity crises, isolation, loneliness, low self-esteem and lack of interest in containing the disease.

Much HIV/AIDS stigma or discrimination involves homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, sex workers, and intravenous drug use.

In many developed countries, a strong correlation exists between HIV/AIDS and male homosexuality or bisexuality (the CDC states, "Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) represent approximately 2% of the United States population, yet are the population most severely affected by HIV"), and association is correlated with higher levels of sexual prejudice such as homophobic attitudes. An early name for AIDS was gay-related immune deficiency or GRID. During the early 1980s, HIV/AIDS was "a disorder that appears to affect primarily male homosexuals".

Some forms of serious discrimination can include: being excluded from consideration for a job, being prohibited from buying a house, needing to pay extra money when renting housing, compulsory HIV testing without prior consent or protection of confidentiality; the quarantine of HIV infected individuals and, in some cases, the loss of property rights when a spouse dies. HIV testing without permission or security may also be considered as wrongdoings against those with HIV. The United States' disability laws prohibit HIV/AIDS discrimination in housing, employment, education, and access to health and social services. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity enforces laws prohibiting housing discrimination based on actual or perceived HIV/AIDS status.

Structural violence

Structural violence is an important factor in the treatment of people

afflicted with AIDS. Paul Farmer argues that social determinants

affecting the lives of certain cultural groups alter their risk of

infections and their ability to access treatment.

For example, access to prophylaxis, access to antiretroviral therapy,

and susceptibility to illness and malnutrition are all factors which

change people's overall risk of illness due to HIV/AIDS. This causes

large difference in the rate of illness due to HIV/AIDS in various

social/cultural groups.

Farmer also argues that social intervention may be key in altering the

gap in treatment between these groups of people. Educating doctors on

the interactions between social life and healthcare would help level out

the injustices in healthcare.

Research

Current

research has found that discrimination against people afflicted with

HIV is a contributing factor for delayed initiation of HIV treatment. As many as 20–40% of Americans who are HIV positive do not begin a care regimen within the first six months after diagnosis.

When individuals begin treatment late in the progression of HIV (when

CD4+ T cell counts are below 500 cells/µL), they have 1.94 times the

risk of mortality compared to those whose treatment is initiated when

CD4+ T cells are still about 500 cells/µL.

In a 2011 study published in AIDS Patient Care and STDs (sample size 215), most of the barriers to care described involve stigma and shame.

The most common reasons of not seeking treatment are "I didn't want to

tell anyone I was HIV-positive", "I didn't want to think about being

HIV-positive", and "I was too embarrassed/ashamed to go".

The presence and perpetuation of HIV stigma prevents many who are able

to obtain treatment from feeling comfortable about addressing their

health statue.

Additional research has found that education decreases HIV/AIDS

discrimination and stigma in communities. A 2015 research study by the

University of Malaya found that in Nigerian populations, "Educating the

population with factual information on HIV/AIDS is needed to reduce

stigma and discrimination towards PLHIV in the community."

Surveys from 56,307 men and women from various educational and

socio-economic levels and ages ranging from 15 to 49 years old, found

that wealthier individuals with secondary and post-secondary were

nonpartisan towards PLHIV. On the contrary, young adults, the poor, and

men were more likely to be biased towards PLHIV. Many people also

believe that AIDS is related to homosexuality.

Even so, research has found that societal structure and beliefs

influence the prevalence stigma and discrimination. "The two concepts of

right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation have

proven to be strong and reliable predictors of different types of

prejudice."

Similar to sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination, the

raised and taught belief to view PLHIV as deviants and outcasts as

children who become adults with warped view of PLHIV. "In order to cope

with threat, people may adhere to a submissive authoritarian ideology,

which will lead them to reject other groups that are perceived as

deviant and may threaten their worldview and their system of values."

There are challenges for medical volunteers and nurses involved

in caring for people with HIV/AIDS. In third-world countries and some

communities in the Americas, low resource funding can make it

detrimental to the success of providing proper care to PLHIV that cannot

otherwise afford healthcare or don't possess medical insurance or other

forms of payments. The nurses or medical volunteers may lack the proper

knowledge of how to treat the individuals too, if they lack resources

and funding. In Province, South Africa, 223 nurses were surveyed on

their qualification and knowledge of AIDS. The nurses scored on Maslach

Burnout Inventory; AIDS Impact Scale and Beck's Depression

Inventory. The total knowledge score obtained by all the participants

ranged from 2 to 16, with an average of 12.93 (SD = 1.92) on HIV/AIDS knowledge.

The rise of PLWH impacts on the already burdened health-care workforce

and predisposes nurses to workplace stress as they carry out their

duties of caring for PLWH.

The discriminatory behaviors of healthcare workers who are expected to

be more knowledgeable about epidemiology and control of HIV including

its social aspects are not helping matters. They often take extreme

precaution against HIV positive clients for fear of transmission, and at

times may refuse HIV positive clients some aspects of care. This is

supported by another study in which health staff was said to be worried

about occupational exposure, with high levels of anxiety and fear when

dealing with HIV-positive persons.

In some countries, to prevent the knowledge of PLHIV, medical reports do not reveal HIV/AIDS study. In Africa, a person's cause of death may be concealed in order for policies to pay out.

This distortion of information does not help in the fight against the

spread of HIV and AIDS. Medical volunteers, nurses, and doctors,

especially in low-income areas, will disclose their status without fear

of rejection, isolation and discriminated against.

The psychological support for PLHIV in certain countries around

the world scarce. In some places like China and Africa, PLHIV have been

noted to have high level of stress due to discrimination and family

members contributes to stress level among PLHIV. Research is still being

done to see if therapy and other psychological services will be a

buffer between the discrimination and stress. The study highlights the

importance to reduce discrimination toward PLHIV and the difficulty to

alleviate its negative consequences. In China, It is warranted to

improve mental health among PLHIV in China and it is still important to

provide in PLHIV as it has direct effects on perceived stress.

PLHIV choose to not tell their HIV status to others, they tend to seek

help from the health care professionals and programs and have

considerable trust towards outside support. Health service providers are

hence promising sources of social support for PLHIV.

Violence

Discrimination

that is violent or threatening violence stops a lot of individuals for

getting tested for HIV, which does not aid in curing the virus.

Violence is an important factor against the treatment of people

afflicted with AIDS. A study done on PLHIV in South Africa shows that

out of a study population of 500, 16.1% of participants reported being

physically assaulted, with 57.7% of those resulting from one's intimate

partners; such as husbands and wives. The available data show high rates

of participants socially isolating themselves from both friends and

family, in addition to avoiding the seeking of treatment at hospitals or

clinics, due to increasing internalized fears.

Any violence against HIV infected individuals or people who are

perceived to be infected with HIV can severely shut down the advancement

of treatment in response to the progression of the disease.

Paul Farmer

argues that social determinants affecting the lives of certain cultural

groups alter their risk of infections and their ability to access

treatment.

For example, access to prophylaxis, access to antiretroviral therapy,

and susceptibility to illness and malnutrition are all factors which

change people's overall risk of illness due to HIV/AIDS. This causes

large difference in the rate of illness due to HIV/AIDS in various

social/cultural groups. Farmer also argues that social intervention may

be key in altering the gap in treatment between these groups of people.

Educating doctors on the interactions between social life and healthcare

would help level out the injustices in healthcare.

Influence on society

Stigma

HIV/AIDS stigma has been further divided into the following three categories:

- Instrumental AIDS stigma—a reflection of the fear and apprehension that are likely to be associated with any deadly and transmissible illness.

- Symbolic AIDS stigma—the use of HIV/AIDS to express attitudes toward the social groups or lifestyles perceived to be associated with the disease.

- Courtesy AIDS stigma—stigmatization of people connected to the issue of HIV/AIDS or HIV- positive people.

HIV-related stigma is very common worldwide.

People who are infected with HIV may be either deliberately or

inadvertently engaged in selective avoidance, ostracism or denigration

of their behaviour.

Research done in South Africa, about the stigma and discrimination in

communities, has found that PLHIV not only experience high levels of

stigma that negatively impact all spheres of their lives, also

interferes psychologically. Internalized stigma and discrimination ran

rampant in the study, but also throughout the PLHIV community. Many

PLHIV in South Africa blamed themselves for their current situation. Globally, nearly half of all people infected with HIV are women.

Stigma, according to Merriam-Webster dictionary, is "a set of

negative and often unfair beliefs that a society or group of people have

about something".

Stigma is often enforced by discrimination, callous actions, and

bigotry. In response, PLHIV have developed self-depreciating mindsets

and coping skills to deal with the social repercussions versus accepting

of their current status and seeking help.

People who are HIV positive often deal with stigma, even though

with the proper medication this can be manageable lifelong disease.And

the existence of AIDS stigma will make AIDS patients under psychological

pressure, which is detrimental to their AIDS treatment. According to

the survey, women with AIDS undertook higher levels of depression,

anxiety and stress than women without AIDS.

It is now possible for a person who HIV+ to have intimate relationship

with someone who is HIV- and not pass the disease to them. It is also

possible for a mother who is HIV+ to not pass it to her child.

In developing countries, people who are HIV+ are discriminated against

at work, school, their community, and even in healthcare facilities.

Discrimination may also increase the spread of HIV because fewer people

will want to get tested. In addition, because of the stigma of AIDS,

people living with AIDS tend to keep their HIV status confidential. They are reluctant to disclose their HIV status to others, including their family, friends and general practitioners. Because AIDS patients choose not to disclose AIDS, which is also likely to increase the spread of AIDS.

Societal relationships

Accordingly,

in countries such as Nigeria, PLHIV are less likely to disclose their

HIV status, due to the repercussion of exclusion of their community. "In

most situations, in order to prevent social rejection, PLHIV will not

disclose their HIV status to avoid being isolated from participating in

the socio-cultural events." This leads to very high-risk behaviors of

passing the illness along to others or delaying the proper treatment.

PLHIV, when shut off from their community. can feel isolated, lonely,

afraid, a lack of motivation, and identity problems. Stigma enhances the

spread and denies the medical research of HIV/AIDS because the social

and medical support are gone. Those individuals can no longer feel like

part of society, which, as humans, we need communities to feel

understood and wanted.

Family and other intimate relationships play a role in the death

rate of PLHIV. Due to the fear of isolation, ignorance, denial, and

discrimination, people will allow HIV to develop into AIDS, further

decreasing life expectancy, since the body's immune system

function will have been significantly lowered. Research done in at

Mvelaphanda Primary School children, in Tembisa, Ekurhuleni Metropolitan

Municipality in Gauteng, South Africa. Many of the children were

orphans due to the death of parents, had sibling deaths, and even some

themselves, who were born with HIV. It was found through survey that if

there is no behavioral change towards HIV/AIDS than no change to fight

the epidemic will occur. At Mvelaphanda Primary school, their mortality

rate is increasing in their children, especially young women. These

women are more at risk than their male counterparts due to many being

involved with older men who have various partners and do not participate

in safe sex practices. Some of these students are themselves parents of

students at the school. The problem is that even when family members

are informed of the cause of death, which is likely to be AIDS, they

choose to inform people that the cause of death was "witchcraft".

Children and other family members tend to deny the truth and are raised

with the belief that HIV and/or AIDS does not exist and they fear to be

bewitched than being infected by the virus.

Along with family bonds and intimate relationships, a spiritual

relationship is strained for PLHIV. In a research study done in the

western region of Saudi Arabia. The stigma is profound in Saudi Arabia

as Islam prohibits behaviours associated with risk factors related to

transmission of HIV, such as non-marital sex, homosexuality and

intravenous drug use. Fear and vulnerability included fear of punishment

from God, fear of being discovered as HIV/ AIDS-positive and fear of

the future and death. PLHIV experienced isolation and lack of

psycho-social and emotional support. In response to their experiences

many participants accepted their diagnoses as destiny and became more

religious, using spirituality as their main coping strategy.