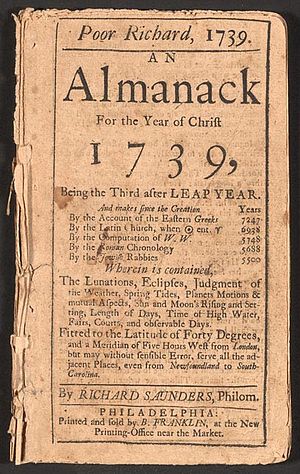

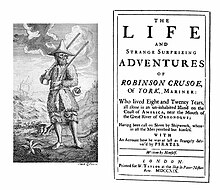

Title page from the first edition

| |

| Author | Daniel Defoe |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adventure, historical fiction |

| Publisher | William Taylor |

Publication date

| 25 April 1719 |

| Followed by | The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe |

Robinson Crusoe[a] (/ˈkruːsoʊ/) is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a travelogue of true incidents.

Epistolary, confessional, and didactic in form, the book is presented as an autobiography of the title character (whose birth name is Robinson Kreutznaer)—a castaway who spends 28 years on a remote tropical desert island near Trinidad, encountering cannibals, captives, and mutineers, before ultimately being rescued. The story has been thought to be based on the life of Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish castaway who lived for four years on a Pacific island called "Más a Tierra", now part of Chile, which was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966.

Despite its simple narrative style, Robinson Crusoe was well received in the literary world and is often credited as marking the beginning of realistic fiction as a literary genre. It is generally seen as a contender for the first English novel. Before the end of 1719, the book had already run through four editions, and it has gone on to become one of the most widely published books in history, spawning so many imitations, not only in literature but also in film, television and radio, that its name is used to define a genre, the Robinsonade.

Plot summary

Pictorial map of Crusoe's island, the "Island of Despair", showing incidents from the book

Crusoe (the family name corrupted from the German name "Kreutznaer") set sail from Kingston upon Hull

on a sea voyage in August 1651, against the wishes of his parents, who

wanted him to pursue a career in law. After a tumultuous journey where

his ship is wrecked in a storm, his lust for the sea remains so strong

that he sets out to sea again. This journey, too, ends in disaster, as

the ship is taken over by Salé pirates (the Salé Rovers) and Crusoe is enslaved by a Moor. Two years later, he escapes in a boat with a boy named Xury; a captain of a Portuguese ship off the west coast of Africa rescues him. The ship is en route to Brazil. Crusoe sells Xury to the captain. With the captain's help, Crusoe procures a plantation.

Years later, Crusoe joins an expedition to bring slaves from Africa,

but he is shipwrecked in a storm about forty miles out to sea on an

island (which he calls the Island of Despair) near the mouth of the Orinoco river on 30 September 1659. He observes the latitude as 9 degrees and 22 minutes north. He sees penguins and seals

on his island. As for his arrival there, only he and three animals,

the captain's dog and two cats, survive the shipwreck. Overcoming his

despair, he fetches arms, tools and other supplies from the ship before

it breaks apart and sinks. He builds a fenced-in habitat near a cave

which he excavates. By making marks in a wooden cross, he creates a

calendar. By using tools salvaged from the ship, and some which he

makes himself, he hunts, grows barley and rice, dries grapes to make

raisins, learns to make pottery and raises goats. He also adopts a

small parrot. He reads the Bible and becomes religious, thanking God

for his fate in which nothing is missing but human society.

More years pass and Crusoe discovers native cannibals,

who occasionally visit the island to kill and eat prisoners. At first

he plans to kill them for committing an abomination but later realizes

he has no right to do so, as the cannibals do not knowingly commit a

crime. He dreams of obtaining one or two servants by freeing some

prisoners; when a prisoner escapes, Crusoe helps him, naming his new

companion "Friday" after the day of the week he appeared. Crusoe then teaches him English and converts him to Christianity.

After more natives arrive to partake in a cannibal feast, Crusoe

and Friday kill most of the natives and save two prisoners. One is

Friday's father and the other is a Spaniard, who informs Crusoe about

other Spaniards shipwrecked on the mainland. A plan is devised wherein

the Spaniard would return to the mainland with Friday's father and bring

back the others, build a ship, and sail to a Spanish port.

Before the Spaniards return, an English ship appears; mutineers

have commandeered the vessel and intend to maroon their captain on the

island. Crusoe and the ship's captain strike a deal in which Crusoe

helps the captain and the loyal sailors retake the ship and leave the

worst mutineers on the island. Before embarking for England, Crusoe

shows the mutineers how he survived on the island and states that there

will be more men coming. Crusoe leaves the island 19 December 1686 and

arrives in England on 11 June 1687. He learns that his family believed

him dead; as a result, he was left nothing in his father's will. Crusoe

departs for Lisbon to reclaim the profits of his estate in Brazil,

which has granted him much wealth. In conclusion, he transports his

wealth overland to England from Portugal to avoid traveling by sea.

Friday accompanies him and, en route, they endure one last adventure together as they fight off famished wolves while crossing the Pyrenees.

Characters

Robinson Crusoe: The narrator of the novel who gets shipwrecked.

Friday: Servant to Robinson Crusoe.

Xury: Former servant to Crusoe, helps him escape Sallee; is later sold to the Portuguese Captain.

The Widow: Friend to Robinson Crusoe. She looks over his assets while he is away.

Portugese Sea Captain: Helps save Robinson Crusoe from slavery. Is very generous and close with Crusoe; helps him with his money and plantation.

Ismael: Secures Robinson Crusoe a boat for escaping Sallee.

The Spaniard: Rescued by Robinson Crusoe and helps him escape his island.

Religion

Robinson Crusoe was published in 1719 during the Enlightenment period of the 18th century. In the novel Crusoe sheds light on different aspects of Christianity and his beliefs. The book can be considered a spiritual autobiography

as Crusoe's views on religion drastically change from the start of his

story and then the end. In the beginning of the book Crusoe is concerned

with sailing away from home, whereupon he meets violent storms at sea.

He promises to God that if he survived that storm he would be a dutiful Christian

man and head home according to his parent's wishes. However, when

Crusoe survives the storm he decides to keep sailing and notes that he

could not fulfil the promises he had made during his turmoil.

After Robinson is shipwrecked on his island he begins to suffer

from extreme isolation. He turns to his animals to talk to, such as his

parrot, but misses human contact. He turns to God during his time of

turmoil in search of solace and guidance. He retrieves a bible from a

ship that was washed along the shore and begins to memorize verses.

In times of trouble he would open the bible to a random page where he

would read a verse that he believed God had made him open and read, and

that would ease his mind. Therefore, during the time in which Crusoe was

shipwrecked he became very religious and often would turn to God for

help.

When Crusoe meets his servant Xury he begins to teach him scripture

and about Christianity. He tried to teach Xury to the best of his

ability about God and what Heaven and Hell was. His purpose was to

convert Xury into being a Christain and wanted to his with him his

values and beliefs. “During the long time that Friday has now been with

me, and that he began to speak to me, and understand me, I was not

wanting to lay a foundation of religious knowledge in his mind;

particularly I ask'd him one time who made him?”

Sources and real-life castaways

Statue of Robinson Crusoe at Alexander Selkirk's birthplace of Lower Largo by Thomas Stuart Burnett

Book on Alexander Selkirk

There were many stories of real-life castaways in Defoe's time. Most famously, Defoe's suspected inspiration for Robinson Crusoe is thought to be Scottish sailor, Alexander Selkirk, who spent four years on the uninhabited island of Más a Tierra (renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966) in the Juan Fernández Islands off the Chilean coast. Selkirk was rescued in 1709 by Woodes Rogers during an English expedition that led to the publication of Selkirk's adventures in both A Voyage to the South Sea, and Round the World and A Cruising Voyage Around the World in 1712. According to Tim Severin,

"Daniel Defoe, a secretive man, neither confirmed or denied that

Selkirk was the model for the hero of his book. Apparently written in

six months or less, Robinson Crusoe was a publishing phenomenon.

The author of Crusoe's Island, Andrew Lambert

states, "the ideas that a single, real Crusoe is a 'false premise'

because Crusoe's story is a complex compound of all the other buccaneer

survival stories." However, Robinson Crusoe

is far from a copy of Rogers' account: Becky Little argues three events

that distinguish the two stories. Robinson Crusoe was shipwrecked while

Selkirk decided to leave his ship thus marooning himself; the island

Crusoe was shipwrecked on had already been inhabited, unlike the

solitary nature of Selkirk's adventures. The last and most crucial

difference between the two stories is Selkirk is a pirate, looting and

raiding coastal cities. "The economic and dynamic thrust of the book is

completely alien to what the buccaneers are doing," Lambert says. "The

buccaneers just want to capture some loot and come home and drink it

all, and Crusoe isn’t doing that at all. He's an economic imperialist.

He's creating a world of trade and profit."

Other possible sources for the narrative include Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, and Spanish sixteenth-century sailor Pedro Serrano. Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan is a twelfth-century philosophical novel also set on a desert island and translated into Latin and English a number of times in the half-century preceding Defoe's novel.

Pedro Luis Serrano was a Spanish sailor who was marooned for

seven or eight years in the sixteenth century on a small desert island

after shipwrecking on a small island in the Caribbean off the coast of

Nicaragua in 1520s. He had no access to fresh water and lived off the

blood and flesh of sea turtles and birds. He was quite a celebrity when

he returned to Europe and before passing away, he recorded the hardships

suffered in documents that show the endless anguish and suffering, the

product of absolute abandonment to his fate, now held in the General Archive of the Indies, in Seville.

It is very likely that Defoe heard his story, 200 years old by then but

still very popular, in one of his visits to Spain before becoming a

writer.

Yet another source for Defoe's novel may have been the Robert Knox account of his abduction by the King of Ceylon Rajasinha II of Kandy in 1659 in An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon.

Tim Severin's book Seeking Robinson Crusoe

(2002) unravels a much wider and more plausible range of potential

sources of inspiration, and concludes by identifying castaway surgeon

Henry Pitman as the most likely. An employee of the Duke of Monmouth, Pitman played a part in the Monmouth Rebellion.

His short book about his desperate escape from a Caribbean penal

colony, followed by his shipwrecking and subsequent desert island

misadventures, was published by John Taylor of Paternoster Row, London, whose son William Taylor

later published Defoe's novel. Severin argues that since Pitman appears

to have lived in the lodgings above the father's publishing house and

that Defoe himself was a mercer in the area at the time, Defoe may have

met Pitman in person and learned of his experiences first-hand, or

possibly through submission of a draft. Severin also discusses another publicised case of a marooned man named only as Will, of the Miskito people of Central America, who may have led to the depiction of Friday.

Arthur Wellesley Secord in his Studies in the Narrative Method of Defoe (1963: 21–111) analyses the composition of Robinson Crusoe

and gives a list of possible sources of the story, rejecting the common

theory that the story of Selkirk is Defoe's only source.

Reception and sequels

Plaque in Queen's Gardens, Hull, showing him on his island

The book was published on 25 April 1719. Before the end of the year, this first volume had run through four editions.

By the end of the nineteenth century, no book in the history of Western literature had more editions, spin-offs and translations (even into languages such as Inuktitut, Coptic and Maltese) than Robinson Crusoe, with more than 700 such alternative versions, including children's versions with pictures and no text.

The term "Robinsonade" was coined to describe the genre of stories similar to Robinson Crusoe.

Defoe went on to write a lesser-known sequel, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

(1719). It was intended to be the last part of his stories, according

to the original title page of the sequel's first edition, but a third

book, Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: With his Vision of the Angelick World (1720), was written.

Interpretations

Crusoe standing over Friday after he frees him from the cannibals

Novelist James Joyce noted that the true symbol of the British Empire

is Robinson Crusoe, to whom he ascribed stereotypical and somewhat

hostile English racial characteristics: "He is the true prototype of the

British colonist. ... The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit in Crusoe: the manly

independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet

efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity."

In a sense Crusoe attempts to replicate his society on the island.

This is achieved through the use of European technology, agriculture and

even a rudimentary political hierarchy. Several times in the novel

Crusoe refers to himself as the "king" of the island, whilst the captain

describes him as the "governor" to the mutineers. At the very end of

the novel the island is explicitly referred to as a "colony". The

idealised master-servant relationship Defoe depicts between Crusoe and

Friday can also be seen in terms of cultural imperialism.

Crusoe represents the "enlightened" European whilst Friday is the

"savage" who can only be redeemed from his barbarous way of life through

assimilation into Crusoe's culture. Nonetheless Defoe also takes the

opportunity to criticise the historic Spanish conquest of South America.

According to J. P. Hunter, Robinson is not a hero but an everyman. He begins as a wanderer, aimless on a sea he does not understand, and ends as a pilgrim, crossing a final mountain to enter the promised land. The book tells the story of how Robinson becomes closer to God, not through listening to sermons in a church but through spending time alone amongst nature with only a Bible to read.

Conversely, cultural critic and literary scholar Michael Gurnow views the novel from a Rousseauian

perspective. In "'The Folly of Beginning a Work Before We Count the

Cost': Anarcho-Primitivism in Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe", the

central character's movement from a primitive state to a more civilized

one is interpreted as Crusoe's denial of humanity's state of nature.

Robinson Crusoe is filled with religious aspects. Defoe was a Puritan moralist and normally worked in the guide tradition, writing books on how to be a good Puritan Christian, such as The New Family Instructor (1727) and Religious Courtship (1722). While Robinson Crusoe

is far more than a guide, it shares many of the themes and theological

and moral points of view. "Crusoe" may have been taken from Timothy

Cruso, a classmate of Defoe's who had written guide books, including God the Guide of Youth (1695), before dying at an early age—just eight years before Defoe wrote Robinson Crusoe.

Cruso would have been remembered by contemporaries and the association

with guide books is clear. It has even been speculated that God the Guide of Youth inspired Robinson Crusoe because of a number of passages in that work that are closely tied to the novel. A leitmotif of the novel is the Christian notion of Providence, penitence and redemption.

Crusoe comes to repent of the follies of his youth. Defoe also

foregrounds this theme by arranging highly significant events in the

novel to occur on Crusoe's birthday. The denouement culminates not only

in Crusoe's deliverance from the island, but his spiritual deliverance,

his acceptance of Christian doctrine, and in his intuition of his own

salvation.

When confronted with the cannibals, Crusoe wrestles with the problem of cultural relativism.

Despite his disgust, he feels unjustified in holding the natives

morally responsible for a practice so deeply ingrained in their culture.

Nevertheless, he retains his belief in an absolute standard of

morality; he regards cannibalism as a "national crime" and forbids

Friday from practising it.

In classical, neoclassical and Austrian economics, Crusoe is regularly used to illustrate the theory of production and choice in the absence of trade, money and prices.

Crusoe must allocate effort between production and leisure and must

choose between alternative production possibilities to meet his needs.

The arrival of Friday is then used to illustrate the possibility of

trade and the gains that result.

Tim Severin's book Seeking Robinson Crusoe

(2002) unravels a much wider range of potential sources of inspiration.

Severin concludes his investigations by stating that the real Robinson

Crusoe figure was Henry Pitman, a castaway who had been surgeon to the Duke of Monmouth. Pitman's short book about his desperate escape from a Caribbean penal colony for his part in the Monmouth Rebellion, his shipwrecking and subsequent desert island misadventures was published by J. Taylor of Paternoster Street, London, whose son William Taylor

later published Defoe's novel. Severin argues that since Pitman

appears to have lived in the lodgings above the father's publishing

house and since Defoe was a mercer

in the area at the time, Defoe may have met Pitman and learned of his

experiences as a castaway. If he did not meet Pitman, Severin points

out that Defoe, upon submitting even a draft of a novel about a castaway

to his publisher, would undoubtedly have learned about Pitman's book

published by his father, especially since the interesting castaway had

previously lodged with them at their former premises.

Severin also provides evidence in his book that another publicised case[24] of a real-life marooned Miskito Central American man named only as Will may have caught Defoe's attention, inspiring the depiction of Man Friday in his novel.

One day, about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man's naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen on the sand.— Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, 1719

The work has been variously read as an allegory for the development

of civilisation; as a manifesto of economic individualism; and as an

expression of European colonial desires. Significantly, it also shows

the importance of repentance and illustrates the strength of Defoe's

religious convictions. Critics such as Maximillian E. Novak support the

connection between the religious and economic themes within Robinson Crusoe,

citing Defoe's religious ideology as the influence for his portrayal of

Crusoe's economic ideals and his support of the individual. Within his

article "Robinson Crusoe's 'Original Sin'", Novak cites Ian Watt's extensive research in Watt's book, Myths of Modern Individualism: Faust, Don Quixote, Don Juan, Robinson Crusoe,

in which Watt explores the impact that several Romantic Era novels had

against economic individualism, and the reversal of those ideals that

takes place within Robinson Crusoe.

In Tess Lewis's review, "The Heroes We Deserve", of Ian Watt's article,

she furthers Watt's argument with a development on Defoe's intention as

an author, "to use individualism to signify nonconformity in religion

and the admirable qualities of self-reliance" (Lewis 678). This further

supports the belief that Defoe used aspects of spiritual autobiography

in order to introduce the benefits of individualism to a not entirely

convinced religious community. J. Paul Hunter has written extensively on the subject of Robinson Crusoe

as apparent spiritual autobiography, tracing the influence of Defoe's

Puritan ideology through Crusoe's narrative, and his acknowledgement of

human imperfection in pursuit of meaningful spiritual engagements—the

cycle of "repentance [and] deliverance." This spiritual pattern and its episodic nature, as well as the re-discovery of earlier female novelists, have kept Robinson Crusoe from being classified as a novel, let alone the first novel written in English—despite the blurbs on some book covers. Early critics, such as Robert Louis Stevenson, admired it, saying that the footprint scene in Crusoe

was one of the four greatest in English literature and most

unforgettable; more prosaically, Dr. Wesley Vernon has seen the origins

of forensic podiatry in this episode. It has inspired a new genre, the Robinsonade, as works such as Johann David Wyss' The Swiss Family Robinson (1812) adapt its premise and has provoked modern postcolonial responses, including J. M. Coetzee's Foe (1986) and Michel Tournier's Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique (in English, Friday, or, The Other Island) (1967). Two sequels followed, Defoe's The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719) and his Serious reflections during the life and surprising adventures of Robinson Crusoe: with his Vision of the angelick world (1720). Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) in part parodies Defoe's adventure novel.

Legacy

The book proved so popular that the names of the two main protagonists have entered the language. During World War II, people who decided to stay and hide in the ruins of the German-occupied city of Warsaw for a period of three winter months, from October to January 1945, when they were rescued by the Red Army, were later called Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw (Robinsonowie warszawscy). Robinson Crusoe usually referred to his servant as "my man Friday", from which the term "Man Friday" (or "Girl Friday") originated.

Robinson Crusoe marked the beginning of realistic fiction as a literary genre. Its success led to many imitators, and castaway novels, written by Ambrose Evans, Penelope Aubin, and others, became quite popular in Europe in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Most of these have fallen into obscurity, but some became established, including The Swiss Family Robinson, which borrowed Crusoe's first name for its title.

Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, published seven years after Robinson Crusoe, may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe's optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man, Warren Montag

argues that Swift was concerned about refuting the notion that the

individual precedes society, as Defoe's novel seems to suggest. In Treasure Island, author Robert Louis Stevenson parodies Crusoe with the character of Ben Gunn,

a friendly castaway who was marooned for many years, has a wild

appearance, dresses entirely in goat skin and constantly talks about

providence.

In Jean-Jacques Rousseau's treatise on education, Emile, or on Education, the one book the protagonist is allowed to read before the age of twelve is Robinson Crusoe.

Rousseau wants Emile to identify himself as Crusoe so he can rely upon

himself for all of his needs. In Rousseau's view, Emile needs to imitate

Crusoe's experience, allowing necessity to determine what is to be

learned and accomplished. This is one of the main themes of Rousseau's

educational model.

Robinson Crusoe bookstore on İstiklal Avenue, Istanbul.

In The Tale of Little Pig Robinson, Beatrix Potter directs the reader to Robinson Crusoe for a detailed description of the island (the land of the Bong tree) to which her eponymous hero moves. In Wilkie Collins' most popular novel, The Moonstone,

one of the chief characters and narrators, Gabriel Betteredge, has

faith in all that Robinson Crusoe says and uses the book for a sort of divination. He considers The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

the finest book ever written, reads it over and over again, and

considers a man but poorly read if he had happened not to read the book.

French novelist Michel Tournier published Friday, or, The Other Island (French Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique)

in 1967. His novel explores themes including civilization versus

nature, the psychology of solitude, as well as death and sexuality in a

retelling of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe story. Tournier's Robinson

chooses to remain on the island, rejecting civilization when offered the

chance to escape 28 years after being shipwrecked. Likewise, in 1963, J. M. G. Le Clézio, winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature, published the novel Le Proces-Verbal. The book's epigraph is a quote from Robinson Crusoe, and like Crusoe, Adam Pollo suffers long periods of loneliness.

"Crusoe in England", a 183-line poem by Elizabeth Bishop, imagines Crusoe near the end of his life, recalling his time of exile with a mixture of bemusement and regret.

J. M. Coetzee's 1986 novel Foe recounts the tale of Robinson Crusoe from the perspective of a woman named Susan Barton.

The story was also illustrated and published in comic book form by Classics Illustrated

in 1943 and 1957. The much improved 1957 version was inked/penciled by

Sam Citron, who is most well known for his contributions to the earlier

issues of Superman.

A pantomime version of Robinson Crusoe was staged at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1796, with Joseph Grimaldi as Pierrot in the harlequinade. The piece was produced again in 1798, this time starring Grimaldi as Clown. In 1815, Grimaldi played Friday in another version of Robinson Crusoe.

Jacques Offenbach wrote an opéra comique called Robinson Crusoé, which was first performed at the Opéra-Comique

in Paris on 23 November 1867. This was based on the British pantomime

version rather than the novel itself. The libretto was by Eugène Cormon and Hector-Jonathan Crémieux.

There have been a number of other stage adaptations, including those by Isaac Pocock, Jim Helsinger and Steve Shaw and a Musical by Victor Prince.

There is a 1927 silent film titled Robinson Crusoe. The Soviet 3D film Robinson Crusoe was produced in 1947. Luis Buñuel directed Adventures of Robinson Crusoe starring Dan O'Herlihy, released in 1954. Walt Disney later comedicized the novel with Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N., featuring Dick Van Dyke. In this version, Friday became a beautiful woman, but named 'Wednesday' instead. Peter O'Toole and Richard Roundtree co-starred in a 1975 film Man Friday

which sardonically portrayed Crusoe as incapable of seeing his

dark-skinned companion as anything but an inferior creature, while

Friday is more enlightened and sympathetic. In 1988, Aidan Quinn portrayed Robinson Crusoe in the film Crusoe. A 1997 movie entitled Robinson Crusoe starred Pierce Brosnan and received limited commercial success. Variations on the theme include the 1954 Miss Robin Crusoe, with a female castaway, played by Amanda Blake, and a female Friday, and the 1964 film Robinson Crusoe on Mars, starring Paul Mantee, with an alien Friday portrayed by Victor Lundin and an added character played by Adam West. The 2000 film Cast Away, with Tom Hanks as a FedEx employee stranded on an Island for many years, also borrows much from the Robinson Crusoe story.

In 1964 a French film production crew made a 13-part serial of The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. It starred Robert Hoffmann.

The black and white series was dubbed into English and German. In the

UK, the BBC broadcast it on numerous occasions between 1965 and 1977. In

1981 Czechoslovakian director and animator Stanislav Látal made a version of the story under the name Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, a Sailor from York

combining traditional and stop-motion animation. The movie was

coproduced by regional West Germany broadcaster Südwestfunk Baden-Baden.

Musician Dean

briefly mentions Crusoe in one of his music videos. In the official

music video for Instagram, there is a part when viewers hear Dean's

distorted voice; "Sometimes, I feel alone . . . I feel like I'm Robinson

Crusoe . . ."

Editions

- The life and strange surprizing adventures of Robinson Crusoe: of York, mariner: who lived eight and twenty years, all alone in an un-inhabited island on the coast of America, near the mouth of the great river of Oroonoque; ... Written by himself., Early English Books Online, 1719. Oxford Text Archive

- Robinson Crusoe, Oneworld Classics 2008. ISBN 978-1-84749-012-4

- Robinson Crusoe, Penguin Classics 2003. ISBN 978-0-14-143982-2

- Robinson Crusoe, Oxford World's Classics 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-283342-6

- Robinson Crusoe, Bantam Classics

- Defoe, Daniel Robinson Crusoe, edited by Michael Shinagel (New York: Norton, 1994), ISBN 978-0393964523. Includes a selection of critical essays.

- Defoe, Daniel. Robinson Crusoe. Dover Publications, 1998.

- Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Rand McNally & Company The Windermere Series 1916. No ISBN. Includes 7 Illustrations by Milo Winter