Threatening the president of the United States is a federal felony under United States Code Title 18, Section 871. It consists of knowingly and willfully mailing or otherwise making "any threat to take the life of, to kidnap, or to inflict bodily harm upon the president of the United States". This also includes presidential candidates and former presidents. The United States Secret Service

investigates suspected violations of this law and monitors those who

have a history of threatening the president. Threatening the president

is considered a political offense. Immigrants who commit this crime can be deported.

Because the offense consists of pure speech, the courts have issued rulings attempting to balance the government's interest in protecting the president with free speech rights under the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. According to the book Stalking, Threatening, and Attacking Public Figures, "Hundreds of celebrity howlers threaten the president of the United States every year, sometimes because they disagree with his policies, but more often just because he is the president."

The prototype for Section 871 was the English Treason Act 1351, which made it a crime to "compass or imagine" the death of the King. Convictions under 18 U.S.C. § 871 have been sustained for declaring that "President Wilson ought to be killed. It is a wonder some one has not done it already. If I had an opportunity, I would do it myself"; and for declaring that "Wilson is a wooden-headed son of a bitch. I wish Wilson was in hell, and if I had the power I would put him there." In a later era, a conviction was sustained for displaying posters urging passersby to "hang [President] Roosevelt".

There has been some controversy among the federal appellate courts as to how the term "willfully" should be interpreted. Traditional legal interpretations of the term are reflected by Black's Law Dictionary's definition, which includes descriptions such as "malicious, done with evil intent, or with a bad motive or purpose," but most courts have adopted a more easily proven standard. For instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held that a threat was knowingly made if the maker comprehended the meaning of the words uttered by him. It was willingly made, if in addition to comprehending the meaning of his words, the maker voluntarily and intentionally uttered them as a declaration of apparent determination to carry them into execution. According to the U.S. Attorney's Manual, "Of the individuals who come to the Secret Service's attention as creating a possible danger to one of their protectees, approximately 75 percent are mentally ill."

Because the offense consists of pure speech, the courts have issued rulings attempting to balance the government's interest in protecting the president with free speech rights under the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. According to the book Stalking, Threatening, and Attacking Public Figures, "Hundreds of celebrity howlers threaten the president of the United States every year, sometimes because they disagree with his policies, but more often just because he is the president."

The prototype for Section 871 was the English Treason Act 1351, which made it a crime to "compass or imagine" the death of the King. Convictions under 18 U.S.C. § 871 have been sustained for declaring that "President Wilson ought to be killed. It is a wonder some one has not done it already. If I had an opportunity, I would do it myself"; and for declaring that "Wilson is a wooden-headed son of a bitch. I wish Wilson was in hell, and if I had the power I would put him there." In a later era, a conviction was sustained for displaying posters urging passersby to "hang [President] Roosevelt".

There has been some controversy among the federal appellate courts as to how the term "willfully" should be interpreted. Traditional legal interpretations of the term are reflected by Black's Law Dictionary's definition, which includes descriptions such as "malicious, done with evil intent, or with a bad motive or purpose," but most courts have adopted a more easily proven standard. For instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held that a threat was knowingly made if the maker comprehended the meaning of the words uttered by him. It was willingly made, if in addition to comprehending the meaning of his words, the maker voluntarily and intentionally uttered them as a declaration of apparent determination to carry them into execution. According to the U.S. Attorney's Manual, "Of the individuals who come to the Secret Service's attention as creating a possible danger to one of their protectees, approximately 75 percent are mentally ill."

Frequency

The first prosecutions under the statute, enacted in 1917, occurred during the highly charged, hyperpatriotic years of World War I,

and the decisions handed down by the courts in these early cases

reflected intolerance for any words demonstrating even a vague spirit of

disloyalty. There was a relative moratorium on prosecutions under this statute until the World War II era. The number increased during the turbulent Vietnam War era. They have tended to fall when the country has not been directly embroiled in a national crisis situation.

The number of reported threats rose from 2,400 in 1965 to 12,800 in 1969. According to Ronald Kessler, President George W. Bush received about 3,000 threats a year, while his successor Barack Obama received about four times that amount. This figure has been disputed by Secret Service Director Mark Sullivan, who says that Obama received about as many threats as the previous two presidents.

According to the U.S. Attorneys' Manual, "Media attention given

to certain kinds of criminal activity seems to generate further criminal

activity; this is especially true concerning presidential threats which

is well documented by data previously supplied by the United States

Secret Service. For example, in the six-month period following the March

30, 1981, attempt on the life of President Reagan,

the average number of threats against protectees of the Secret Service

increased by over 150 percent from a similar period during the prior

year." For this reason, the agency recommends considering the use of

sealed affidavits to keep news of threats from leaking to the press.

Incidents

Convictions

under 18 U.S.C. § 871 have been sustained for declaring that "President

Wilson ought to be killed. It is a wonder some one has not done it

already. If I had an opportunity, I would do it myself.";

and for declaring that "Wilson is a wooden-headed son of a bitch. I

wish Wilson was in hell, and if I had the power I would put him there." In a later era, a conviction was sustained for displaying posters urging passersby to "hang [President Franklin D.] Roosevelt".

In a 1971 interview, comedian Groucho Marx told Flash magazine, "I think the only hope this country has is Nixon’s assassination." U.S. Attorney James L. Browning, Jr.

opined, "It is one thing to say that 'I (or we) will kill Richard

Nixon' when you are the leader of an organization which advocates

killing people and overthrowing the Government; it is quite another to

utter the words which are attributed to Mr. Marx, an alleged comedian."

This cartoon by Michael Ramirez led to his questioning by the Secret Service.

In July 2003, the Los Angeles Times published a Sunday editorial cartoon by conservative Michael Ramirez that depicted a man pointing a gun at President Bush’s head; it was a takeoff on the 1969 Pulitzer Prize-winning photo by Eddie Adams that showed South Vietnamese National Police Chief Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner (Capt. Nguyễn Văn Lém) at point-blank range. The cartoon prompted a visit from the Secret Service, but no charges were filed.

In 2005, a teacher instructed her senior civics and economics

class to take photographs to illustrate the rights contained in the United States Bill of Rights.

One student "had taken a photo of George Bush out of a magazine and

tacked the picture to a wall with a red thumb tack through his head.

Then he made a thumb's-down sign with his own hand next to the president's picture, and he had a photo taken of that, and he pasted it on a poster." A Wal-Mart photo department employee reported it to police, and the Secret Service investigated. No charges were filed.

In 2007, Purdue University teaching assistant Vikram Buddhi was convicted of posting messages to Yahoo Finance criticizing the Iraq War and stating, "Call for the assassination of GW Bush" and "Rape and Kill Laura Bush." The defense had argued that the defendant never explicitly threatened anyone.

In September 2009 the Secret Service investigated Facebook polls that asked whether President Barack Obama should be assassinated. Some question has arisen as to how to handle Facebook groups such as "LETS KILL BUSH WITH SHOES" (a reference to the 2008 Muntadhar al-Zaidi shoe incident) which had 484 members as of September 2009; similar issues have arisen on MySpace. Tweets

have come under Secret Service investigation, including ones that said

"ASSASSINATION! America, we survived the Assassinations and Lincoln

& Kennedy. We'll surely get over a bullet to Barrack [sic]

Obama's head," and "The next American with a Clear Shot should drop

Obama like a bad habit. 4get Blacks or his claims to b[e] Black. Turn on

Barack Obama."

In 2010, Johnny Logan Spencer Jr. was sentenced in Louisville,

Kentucky, to 33 months in prison for posting a poem entitled "The

Sniper" about the president's assassination on a white supremacist

website. He apologized in court, saying that he was, as WHAS news put

it, "upset about his mother's death and had fallen in with a white

supremacist group that had helped him kick a drug habit."

In 2010, Brian Dean Miller was sentenced in Texas to 27 months in prison for posting to Craigslist:

"People, the time has come for revolution. It is time for Obama to die.

I am dedicating my life to the death of Obama and every employee of the

federal government. As I promised in a previous post, if the health care reform bill passed I would become a terrorist. Today I become a terrorist."

Later in 2010, a 77-year-old white

man named Michael Stephen Bowden, who said that President Obama was not

doing enough to help African Americans, was arrested after making murder-suicide threats against Obama.

On July 19, 2011, the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals reversed

the conviction of Walter Bagdasarian for making online threats against

Obama. The court found that his speech urging Obama's assassination

("Re: Obama fk the niggar [sic], he will have a 50 cal

in the head soon" and "shoot the nig country fkd for another 4 years+,

what nig has done ANYTHING right???? long term???? never in history,

except sambos") was protected by the First Amendment.

History

The prototype for Section 871 was the British Treason Act 1351, which made it a crime to "compass or imagine" the death of the King.

The statute prohibiting threats against the president was enacted by

Congress in 1917. The maximum fine it allowed was $1,000. The law was

amended in 1994 to increase the maximum fine to $250,000.

Among the justifications that have been given for the statute

include arguments that threats against the president have a tendency to

stimulate opposition to national policies, however wise, even in the

most critical times; to incite the hostile and evil-minded to take the

president's life; to add to the expense of the president's safeguarding;

to be an affront to all loyal and right-thinking persons; to inflame

their minds; to provoke resentment, disorder, and violence; and to disrupt presidential activity and movement. It has also been argued that such threats are akin to treason and can be rightly denounced as a crime against the people as the sovereign power. Congressman Edwin Y. Webb

noted, "That is one reason why we want this statute – in order to

decrease the possibility of actual assault by punishing threats to

commit an assault ... A bad man can make a public threat, and put

somebody else up to committing a crime against the Chief Executive, and

that is where the harm comes. The man who makes the threat is not

himself very dangerous, but he is liable to put devilment in the mind of

some poor fellow who does try to harm him."

Prisoners are sometimes charged for threatening the president

though they lack the ability to personally carry out such a threat. The

courts have upheld such convictions, reasoning that actual ability to carry out the threat is not an element of the offense;

prisoners are able to make true threats as they could carry out the

threat by directing people on the outside to harm the president. Sometimes prisoners make such threats to manipulate the system; e.g., a case arose in which an inmate claiming to be "institutionalized"

threatened the president in order to stay in prison; there was a case

in which a state prisoner threatened the president because he wanted to

go to a federal institution.

Penalties

Threatening the president of the United States is a felony under United States Code Title 18, Section 871. The offense is punishable by up to 5 years in prison, a $250,000 maximum fine, a $100 special assessment, and 3 years of supervised release. Internet restrictions such as a prohibition on access to email have been imposed on offenders who made their threats by computer. The U.S. Sentencing Guidelines

set a base offense level of 12 for sending threatening communication,

but when a threat to the president is involved, a 6-level "official

victim" enhancement applies. Moreover, "an upward departure may be

warranted due to the potential disruption of the governmental function."

Further enhancements can apply if the offender evidenced an intent to

carry out the threat (6-level enhancement); made more than two threats

(2-level enhancement); caused substantial disruption of public,

governmental, or business functions or services (4-level enhancement);

or created a substantial risk of inciting others to harm federal

officials (2-level enhancement).

Since each 6-level increase approximately doubles the Guidelines

sentencing range, it is not particularly rare for an offender who

threatens the president to receive a sentence at or near the maximum,

especially if he/she has a criminal history and/or does not qualify for a

reduction for acceptance of responsibility.

There is a 4-level decrease available for a threat involving a "single

instance evidencing little or no deliberation", which would usually

apply to spur-of-the-moment verbal threats. The maximum penalty for threatening a United States judge or a Federal law enforcement officer is 10 years imprisonment — double the maximum penalty for threatening the president.

Interpretation

There

has been some controversy among the federal appellate courts as to how

the term "willfully" should be interpreted. Traditional legal

interpretations of the term are reflected by Black's Law Dictionary's definition, which includes descriptions such as "malicious, done with evil intent, or with a bad motive or purpose." In U.S. v. Patillo, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

held that a threat to the president could lead to a verdict of guilty

"only if made with the present intention to do injury to the president".

Specifically, the court opined that "The word [willfully] often denotes

an act which is intentional, or knowing, or voluntary, as distinguished

from accidental. But when used in a criminal statute it generally means

an act done with a bad purpose...We believe that a 'bad purpose'

assumes even more than its usual importance in a criminal prosecution

based upon the bare utterance of words."

Most of the other circuits have held that it is not necessary

that the threat be intended to be communicated to the president or that

it have tendency to influence his action. The legislative history,

which contains debate over a rejected amendment that would have

eliminated the words "knowingly and willfully" from the statute,

reflects that the word "willfully" was included in order to avoid

criminalizing behavior carried out with innocent intent (e.g. mailing to

a friend, for informational purposes, a newspaper article containing a

threat to the president). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

held that a threat was knowingly made if the maker comprehended the

meaning of the words uttered by him. It was willingly made, if in

addition to comprehending the meaning of his words, the maker

voluntarily and intentionally uttered them as a declaration of apparent

determination to carry them into execution.

Watts v. United States

In the case of Watts v. United States 394 U.S. 705 (1969), the United States Supreme Court ruled that mere political hyperbole must be distinguished from true threats. At a DuBois Club public rally on the Washington Monument

grounds, a member of the assembled group suggested that the young

people present should get more education before expressing their views.

The defendant, an 18-year-old, replied:

They always holler at us to get an education. And now I have already received my draft classification as 1-A and I have got to report for my physical this Monday coming. I am not going. If they ever make me carry a rifle the first man I want to get in my sights is L. B. J.

According to court testimony, the defendant in speaking made a

gesture of sighting down the barrel of a rifle. The audience responded

with laughter and applause, which the Court of Appeals would later view

as potentially ominous:

[I]t has not been unknown for laughter and applause to have sinister implications for the safety of others. History records that applause and laughter frequently greeted Hitler's predictions of the future of the German Jews. Even earlier, the Roman holidays celebrated in the Colosseum often were punctuated by cheers and laughter when the Emperor gestured thumbs down on a fallen gladiator.

The boy was arrested and found to be in possession of cannabis, but a Court of General Sessions Judge suppressed

the cannabis because he found that there had been no probable cause for

the Secret Service agents to believe the defendant's words constituted a

threat to the president. This did not prevent a federal court from convicting him for threatening the president. The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

affirmed his conviction, but the Supreme Court reversed, stating, "We

agree with petitioner that his only offense here was 'a kind of very

crude offensive method of stating a political opposition to the

president.' Taken in context, and regarding the expressly conditional

nature of the statement and the reaction of the listeners, we do not see

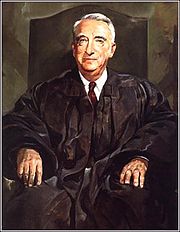

how it could be interpreted otherwise." In a concurring opinion, William O. Douglas noted, "The Alien and Sedition Laws

constituted one of our sorriest chapters; and I had thought we had done

with them forever ... Suppression of speech as an effective police

measure is an old, old device, outlawed by our Constitution."

Other cases

Courts

have held that a person is guilty of the offense if certain criteria

are met. Specifically, the person must intentionally make a threat in a

context, and under such circumstances, that a reasonable person would

foresee that the statement would be interpreted by persons hearing or

reading it as a serious expression of an intention to harm the

president. The statement must also not be the result of mistake, duress

or coercion. A true threat is a serious threat and not words uttered as a mere political argument, idle talk, or jest. The standard definition of a true threat does not require actual subjective intent to carry out the threat.

A defendant's statement that if they got the chance they would

harm the president is a threat; merely because a threat has been

conditional upon the ability of the defendant to carry it out does not

render it any less of a threat.

It has been ruled that taken together, envelopes containing ambiguous

messages, white powder, and cigarette butts that were mailed to the

president after the 9/11 anthrax outbreaks conveyed a threatening message. The sending of non-toxic white powder alone to the president has been deemed to be a threat.

A broad statement that the president must "see truth" and "uphold

Constitution" or else the letter writer will put a bullet in his head

count as not expressly conditional as it does not indicate what events

or circumstances will prevent the threat from being carried out.

However, the statement "if I got hold of President Wilson, I would

shoot him" was not an indictable offense because the conditional threat

was ambiguous as to whether it was an expression of present or past

intent.

The posting of a paper in a public place with a statement that it

would be an acceptable sacrifice to God to kill an unjust president was

ruled not to be in violation of the statute.

The statute does not penalize imagining, wishing, or hoping that the

act of killing the president will be committed by someone else.

Conversely, the mailing of letters containing the words "kill Reagan"

and depicting the president's bleeding head impaled on a stake was

considered a serious threat. An oral threat against the president unheard by anyone does not constitute a threat denounced by statute.

Since other statutes make it a crime to assault or to attempt to

kill the president, some question has arisen as to whether it is

necessary to have a statute banning threats. As the Georgetown Law Journal

notes, "It can be argued that the punishment of an attempt against the

life of the president is not sufficient; by the time all the elements of

an attempt have come into existence the risk to the president becomes

too great. On the other hand, the punishment of conduct short of an

attempt runs the risk of violating the established principle that intent

alone is not punishable ... While ordinarily mere preparation to commit

an offense is not punishable, an exception may perhaps be justified by

the seriousness of the consequences of an executed threat on the

president's life."

Psychiatric matters

According

to the U.S. Attorney's Manual, "Of the individuals who come to the

Secret Service's attention as creating a possible danger to one of their

protectees, approximately 75 percent are mentally ill."

The Secret Service notes, "These are probably Secret Service's most

serious cases because it must be determined whether the person making

the threat really wants to hurt [Secret Service protectees] or whether

they may have some medical problems of their own, for which they need

help." It is not uncommon for judges to order psychological evaluations of defendants charged under this statute in accordance with United States federal laws governing offenders with mental diseases or defects.

Psychiatrists divide people who threaten the president into three

classes: Class 1 includes persons who have expressed overt threatening

statements but have made no overt action, Class 2 comprises individuals

who have a history of assaultive behaviors toward authority figures, and

Class 3 includes person who are considered dangerous and typically have

been prosecuted under Section 871.

Dilemmas related to patient confidentiality sometimes arise when a

mentally ill subject makes a threat against the president. The

termination of nurse Linda Portnoy was upheld after she reported such a

statement to the Secret Service. The court noted that the patient was

restrained and unable to act on his threats, so he wasn't an immediate

safety risk. It also considered the patient's psychiatrist, not Portnoy,

the appropriate person to assess the gravity of his threats.

In a study found that in those who threaten the president, the primary

differentiating variable related to lethality was "opportunity and

happenstance". Conversely, a defendant's writings in his anger management

workbook threatening to kill the president upon the defendant's release

from the penitentiary were ruled to have fallen within the dangerous

patient exception to psychotherapist-patient privilege.

Federal law provides that the director of the facility in which a person is hospitalized due to being found incompetent to stand trial or not guilty only by reason of insanity

of a Section 871 violation shall prepare annual or semiannual reports

concerning the mental condition of the person and containing

recommendations about the need for his continued hospitalization; a copy

of the reports shall be submitted to the Director of the United States

Secret Service to assist it in carrying out its protective duties.

The Ninth Circuit ruled that it is constitutional to hold a

presidential threatener beyond Section 871's prescribed five-year

statutory maximum if he is found to be dangerous and mentally ill. It is

possible under federal law to hold some presidential threateners

indefinitely.