Martin Heidegger (/ˈhaɪdɛɡər, ˈhaɪdɪɡər/; German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈhaɪdɛɡɐ]; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher and a seminal thinker in the Continental tradition of philosophy. He is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism.

In Being and Time (1927), Heidegger addresses the meaning of "being" by considering the question, "what is common to all entities that makes them entities?" Heidegger approaches this question through an analysis of Dasein, his term for the specific type of being that humans possess, and which he associates closely with his concept of "being-in-the-world" (In-der-Welt-sein). This conception of the human is in contrast with that of Rationalist thinkers like René Descartes, who had understood human existence most basically as thinking, as in Cogito ergo sum ("I think therefore I am").

Heidegger's later work includes criticism of the view, common in the Western tradition, that all of nature is a "standing reserve" on call for human purposes.

Heidegger was a member and supporter of the Nazi Party. There is controversy as to the relationship between his philosophy and his Nazism.

Biography

Early years

The Mesnerhaus in Meßkirch, where Heidegger grew up

Heidegger was born in rural Meßkirch, Baden-Württemberg, the son of Johanna (Kempf) and Friedrich Heidegger. Raised a Roman Catholic, he was the son of the sexton of the village church that adhered to the First Vatican Council

of 1870, which was observed mainly by the poorer class of Meßkirch. His

family could not afford to send him to university, so he entered a Jesuit seminary,

though he was turned away within weeks because of the health

requirement and what the director and doctor of the seminary described

as a psychosomatic

heart condition. Heidegger was short and sinewy, with dark piercing

eyes. He enjoyed outdoor pursuits, being especially proficient at

skiing.

Studying theology at the University of Freiburg while supported by the church, later he switched his field of study to philosophy. Heidegger completed his doctoral thesis on psychologism in 1914, influenced by Neo-Thomism and Neo-Kantianism, directed by Arthur Schneider. In 1916, he finished his venia legendi with a habilitation thesis on Duns Scotus directed by Heinrich Rickert and influenced by Edmund Husserl's phenomenology.

In the two years following, he worked first as an unsalaried Privatdozent then served as a soldier during the final year of World War I; serving "the last ten months of the war" with "the last three of those in a meteorological unit on the western front".

Marburg

In 1923, Heidegger was elected to an extraordinary Professorship in Philosophy at the University of Marburg. His colleagues there included Rudolf Bultmann, Nicolai Hartmann, and Paul Natorp. Heidegger's students at Marburg included Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hannah Arendt, Karl Löwith, Gerhard Krüger, Leo Strauss, Jacob Klein, Günther Anders, and Hans Jonas. Following on from Aristotle,

he began to develop in his lectures the main theme of his philosophy:

the question of the sense of being. He extended the concept of subject

to the dimension of history and concrete existence, which he found prefigured in such Christian thinkers as Saint Paul, Augustine of Hippo, Luther, and Kierkegaard. He also read the works of Wilhelm Dilthey, Husserl, Max Scheler, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Freiburg

In 1927, Heidegger published his main work Sein und Zeit (Being and Time).

When Husserl retired as Professor of Philosophy in 1928, Heidegger

accepted Freiburg's election to be his successor, in spite of a

counter-offer by Marburg. Heidegger remained at Freiburg im Breisgau for the rest of his life, declining a number of later offers, including one from Humboldt University of Berlin. His students at Freiburg included Hannah Arendt, Günther Anders, Hans Jonas, Karl Löwith, Charles Malik, Herbert Marcuse and Ernst Nolte. Emmanuel Levinas attended his lecture courses during his stay in Freiburg in 1928.

Heidegger was elected rector of the University on 21 April 1933, and joined the National Socialist German Workers' (Nazi) Party on 1 May.

During his time as rector of Freiburg, Heidegger was not only a member

of the Nazi Party, but an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis. There is controversy as to the relationship between his philosophy and his Nazism.

He wanted to position himself as the philosopher of the Party, but the

highly abstract nature of his work and the opposition of Alfred Rosenberg,

who himself aspired to act in that position, limited Heidegger's role.

His resignation from the rectorate owed more to his frustration as an

administrator than to any principled opposition to the Nazis, according

to historians.

In his inaugural address as rector on 27 May he expressed his support

of a German revolution, and in an article and a speech to the students

from the same year he also supported Adolf Hitler. In November 1933, Heidegger signed the Vow

of allegiance of the Professors of the German Universities and

High-Schools to Adolf Hitler and the National Socialistic State.

Heidegger resigned the rectorate in April 1934, but remained a

member of the Nazi Party until 1945 even though (as Julian Young

asserts) the Nazis eventually prevented him from publishing. In the autumn of 1944, Heidegger was drafted into the Volkssturm, assigned to dig anti-tank ditches along the Rhine.

Heidegger's Black Notebooks, written between 1931 and 1941 and first published in 2014, contain several expressions of anti-semitic sentiments, which have led to a re-evaluation of Heidegger's relation to Nazism. Having analysed the Black Notebooks, Donatella di Cesare asserts in her book Heidegger and the Jews

that "metaphysical anti-Semitism" and antipathy toward Jews were

central to Heidegger's philosophical work. Heidegger, according to di

Cesare, considered Jewish people to be agents of modernity disfiguring

the spirit of Western civilization; he held the Holocaust to be the

logical result of the Jewish acceleration of technology, and thus blamed

the Jewish genocide on its victims themselves.

Post-war

In late 1946, as France engaged in épuration légale in its Occupation zone,

the French military authorities determined that Heidegger should be

blocked from teaching or participating in any university activities

because of his association with the Nazi Party. The denazification procedures against Heidegger continued until March 1949 when he was finally pronounced a Mitläufer

(the second lowest of five categories of "incrimination" by association

with the Nazi regime). No punitive measures against him were proposed. This opened the way for his readmission to teaching at Freiburg University in the winter semester of 1950–51. He was granted emeritus status and then taught regularly from 1951 until 1958, and by invitation until 1967.

Personal life

Heidegger's stone-and-tile chalet clustered among others at Todtnauberg

Heidegger married Elfride Petri on 21 March 1917, in a Catholic ceremony officiated by his friend Engelbert Krebs, and a week later in a Protestant ceremony in the presence of her parents. Their first son, Jörg, was born in 1919. Elfride then gave birth to Hermann

in August 1920. Heidegger knew that he was not Hermann's biological

father but raised him as his son. Hermann's biological father, who

became godfather to his son, was family friend and doctor Friedel

Caesar. Hermann was told of this at the age of 14; Hermann became a historian and would later serve as the executor of Heidegger's will. Hermann Heidegger died on 13 January 2020.

Heidegger had a long romantic relationship with Hannah Arendt and an affair (over many decades) with Elisabeth Blochmann, both students of his. Arendt was Jewish, and Blochmann had one Jewish parent, making them subject to severe persecution by the Nazi authorities.

He helped Blochmann emigrate from Germany before the start of World War

II and resumed contact with both of them after the war. Heidegger's letters to his wife contain information about several other affairs of his.

Heidegger spent much time at his vacation home at Todtnauberg, on the edge of the Black Forest. He considered the seclusion provided by the forest to be the best environment in which to engage in philosophical thought.

Heidegger's grave in Meßkirch

A few months before his death, he met with Bernhard Welte, a Catholic

priest, Freiburg University professor and earlier correspondent. The

exact nature of their conversation is not known, but what is known is

that it included talk of Heidegger's relationship to the Catholic Church

and subsequent Christian burial at which the priest officiated. Heidegger died on 26 May 1976, and was buried in the Meßkirch cemetery.

Philosophy

Being, time, and Dasein

Heidegger

thought the presence of things for us is not their being, but in their

utility. For instance, when a hammer is used to knock in a nail, we do

not attend to the hammer in itself but are aware of it only as a

"ready-to-hand" extension of ourselves to achieve a future result: the

knocking in of the nail. The past (the existing or "given" hammer) is

reduced to a future usefulness (the driven nail). Zuhanden

(readiness-to-hand), in which the distinction between subject and object

is blurred, is one of three modes of Being that Heidegger identified –

the others being Vorhanden (presence-at-hand), for things that are there but that we don't interact with, and Dasein (human existence).

Heidegger claimed philosophy and science since ancient Greece had

reduced things to their presence, which was a superficial way of

understanding them. One crucial source of this insight was Heidegger's

reading of Franz Brentano's

treatise on Aristotle's manifold uses of the word "being", a work which

provoked Heidegger to ask what kind of unity underlies this

multiplicity of uses. Heidegger opens his magnum opus, Being and Time, with a citation from Plato's Sophist

indicating that Western philosophy has neglected Being because it was

considered too obvious to question. Heidegger's intuition about the

question of Being is thus a historical argument, which in his later work

becomes his concern with the "history of Being", that is, the history

of the forgetting of Being, which according to Heidegger requires that

philosophy retrace its footsteps through a productive destruction of the history of philosophy.

The second intuition animating Heidegger's philosophy derives

from the influence of Husserl, a philosopher largely uninterested in

questions of philosophical history. Rather, Husserl argued that all that

philosophy could and should be is a description of experience (hence

the phenomenological slogan, "to the things themselves"). But for

Heidegger, this meant understanding that experience is always already situated in a world and in ways of being. Thus Husserl's understanding that all consciousness is "intentional" (in the sense that it is always intended toward

something, and is always "about" something) is transformed in

Heidegger's philosophy, becoming the thought that all experience is

grounded in Sorge, which means the anxiety or worrifulness arising out

of concern about the future—referring to the inner state of being as

well as external causality of that being. Heidegger also employs two

cognates of Sorge; Besorgen - provision of something for oneself or

someone else, and Fursorge - solicitude or caring for another in need of

help. This thicket of meaning around care/concern (Sorge) is the basis

of Heidegger's "existential analytic", as he develops it in Being and Time.

Heidegger argues that describing experience properly entails finding

the being for whom such a description might matter. Heidegger thus

conducts his description of experience with reference to "Dasein", the being for whom Being is a question. In everyday German, "Dasein" means "existence." It is composed of "Da" (here/there) and "Sein" (being). Dasein is transformed in Heidegger's usage from its everyday meaning to refer, rather, to that being that is there in its world, that is, the being for whom being matters. In later publications Heidegger writes the term in hyphenated form as Da-sein, thus emphasizing the distance from the word's ordinary usage.

In Being and Time, Heidegger criticized the abstract and

metaphysical character of traditional ways of grasping human existence

as rational animal, person, man, soul, spirit, or subject. Dasein, then, is not intended as a way of conducting a philosophical anthropology, but is rather understood by Heidegger to be the condition of possibility for anything like a philosophical anthropology. Dasein, according to Heidegger, is care. The world confronts Dasein with possibilities. It is not completely deterministic; Dasein has choices. But Dasein

cannot choose not to face the possibilities presented by the world,

including the inevitability of its own mortality. Heidegger in his

existential analytic refers to this condition as being "thrown into the

world", or "thrownness" (Geworfenheit). The need for Dasein

to assume these possibilities, that is, the need to be responsible for

one's own existence, is the basis of Heidegger's notions of authenticity

and resoluteness—that is, of those specific possibilities for Dasein which depend on escaping the "vulgar" temporality of calculation and of public life.

The marriage of these two observations depends on the fact that each of them is essentially concerned with time. That Dasein is thrown into an already existing world and thus into its mortal possibilities does not only mean that Dasein is an essentially temporal being; it also implies that the description of Dasein

can only be carried out in terms inherited from the Western tradition

itself. For Heidegger, unlike for Husserl, philosophical terminology

could not be divorced from the history of the use of that terminology,

and thus genuine philosophy could not avoid confronting questions of

language and meaning. The existential analytic of Being and Time was thus always only a first step in Heidegger's philosophy, to be followed by the "dismantling" (Destruktion)

of the history of philosophy, that is, a transformation of its language

and meaning, that would have made of the existential analytic only a

kind of "limit case" (in the sense in which special relativity is a

limit case of general relativity).

That Heidegger did not write this second part of Being and Time,

and that the existential analytic was left behind in the course of

Heidegger's subsequent writings on the history of being, might be

interpreted as a failure to conjugate his account of individual experience with his account of the vicissitudes of the collective

human adventure that he understands the Western philosophical tradition

to be. And this would in turn raise the question of whether this

failure is due to a flaw in Heidegger's account of temporality, that is,

of whether Heidegger was correct to oppose vulgar and authentic time.

There are also recent critiques in this regard that were directed at

Heidegger's focus on time instead of primarily thinking about being in

relation to place and space, and to the notion of dwelling, with connections too to architectural theory as impacted by phenomenology.

Being and Time

View from Heidegger's vacation chalet in Todtnauberg. Heidegger wrote most of Being and Time there.

Heidegger's first academic book, Being and Time (German title: Sein und Zeit), was published in 1927. He had been under pressure to publish in order to qualify for Husserl's chair at the University of Freiburg; he dedicated the book to Husserl and the success of the work ensured his appointment to the post.

In Being and Time, Heidegger investigates the question of being by asking about the being for whom being is a question. Heidegger names this being Dasein (see above), and he pursues his investigation through themes such as mortality, care,

anxiety, temporality, and historicity. It was Heidegger's original

intention to write a second half of the book, consisting of a "Destruktion"

of the history of philosophy—that is, the transformation of philosophy

by re-tracing its history—but he never completed this project.

Later works: The Turn

Am Feldweg in Meßkirch. Heidegger often went for a walk on the path in this field. See the text Der Feldweg GA Nr. 13

Heidegger's later works, beginning by 1930 and largely established by the early 1940s, seem to many commentators (e.g. William J. Richardson)

at least to reflect a shift of focus, if not indeed a major change in

his philosophical outlook, which is known as "the turn" (die Kehre). One way this has been understood is as a shift from "dwelling" in the world (Wohnen)

to a fixation on more superficial activities ("doing"), typified by a

"will to power" kind of dominion over the world as a mere object. This

ontological "turn" can be seen as a shift in priority from Being and Time to Time and Being—namely, from dwelling (being) in the world to doing (time) in the world.

(This aspect had a particular influence on architectural theorists in

their focus on place and space in thinking about dwelling. Such is the

case with the work of Christian Norberg-Schulz and the philosopher-architect Nader El-Bizri.) However, others feel that this is to overstate the difference. For example, in 2011 Mark Wrathall

argued that Heidegger pursued and refined the central notion of

unconcealment throughout his life as a philosopher. Its importance and

continuity in his thinking, Wrathall states, shows that he did not have a

"turn". A reviewer of Wrathall's book stated: "An ontology of

unconcealment [...] means a description and analysis of the broad

contexts in which entities show up as meaningful to us, as well as the

conditions under which such contexts, or worlds, emerge and fade."

Heidegger focuses less on the way in which the structures of

being are revealed in everyday behavior, and more on the way in which

behavior itself depends on a prior "openness to being." The essence of

being human is the maintenance of this openness. This ‘openness to

being' can be seen as a basic ability of humans. We experience the world

of beings as containing things in which we have an interest or concern.

Heidegger contrasts this openness to the "will to power" of the modern

human subject, which is one way of forgetting this originary openness.

Heidegger understands the commencement of the history of Western

philosophy as a brief period of authentic openness to being, during the

time of the pre-Socratics, especially Anaximander, Heraclitus, and Parmenides.

This was followed, according to Heidegger, by a long period

increasingly dominated by the forgetting of this initial openness, a

period which commences with Plato, and which occurs in different ways throughout Western history.

Two recurring themes of Heidegger's later writings are poetry and

technology. Heidegger sees poetry and technology as two contrasting

ways of "revealing."

Poetry reveals being in the way in which, if it is genuine poetry, it

commences something new. Technology, on the other hand, when it gets

going, inaugurates the world of the dichotomous subject and object,

which modern philosophy commencing with Descartes also reveals. But with

modern technology a new stage of revealing is reached, in which

the subject-object distinction is overcome even in the "material" world

of technology. The essence of modern technology is the conversion of the

whole universe of beings into an undifferentiated "standing reserve" (Bestand) of energy available for any use to which humans choose to put it. Heidegger described the essence of modern technology as Gestell,

or "enframing." He does not unequivocally condemn technology: while he

acknowledges that modern technology contains grave dangers, Heidegger

nevertheless also argues that it may constitute a chance for human

beings to enter a new epoch in their relation to being. Despite this, some commentators have insisted that an agrarian nostalgia permeates his later work.

In a 1950 lecture he formulated the famous saying "Language speaks", later published in the 1959 essays collection Unterwegs zur Sprache, and collected in the 1971 English book Poetry, Language, Thought.

Heidegger's later works include Vom Wesen der Wahrheit ("On the Essence of Truth", 1930), Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes ("The Origin of the Work of Art", 1935), Einführung in die Metaphysik ("Introduction to Metaphysics", 1935), Bauen Wohnen Denken ("Building Dwelling Thinking", 1951), and Die Frage nach der Technik ("The Question Concerning Technology", 1954) and Was heisst Denken? (What Is Called Thinking? 1954). Also Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis) (Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning)), composed in the years 1936–38 but not published until 1989, on the centennial of Heidegger's birth.

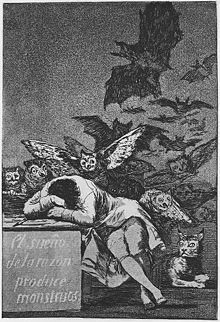

Heidegger and the ground of history

It has been postulated that Heidegger believed the Western world to be on a trajectory headed for total war, and on the brink of profound nihilism (the rejection of all religious and moral principles), which would be the purest and highest revelation of Being itself, offering a horrifying crossroads of either salvation or the end of metaphysics and modernity; rendering the West a wasteland populated by tool-using brutes, characterized by an unprecedented ignorance and barbarism in which everything is permitted.

He thought the latter possibility would degenerate mankind generally into scientists, workers and brutes, living under the last mantle of one of three ideologies, Americanism, Marxism or Nazism (which he deemed metaphysically identical, as avatars of subjectivity and institutionalized nihilism), and an unfettered totalitarian world technology.

Supposedly, this epoch would be ironically celebrated, as the most enlightened and glorious in human history.

He envisaged this abyss to be the greatest event in the West's

history because it would enable Humanity to comprehend Being more

profoundly and primordially than the Pre-Socratics.

Influences

St. Augustine of Hippo

Recent scholarship has shown that Heidegger was substantially influenced by St. Augustine of Hippo and that Being and Time would not have been possible without the influence of Augustine's thought. Augustine's Confessions was particularly influential in shaping Heidegger's thought.

Augustine viewed time as relative and subjective, and that being and time were bound up together.

Heidegger adopted similar views, e.g. that time was the horizon of

Being: ' ...time temporalizes itself only as long as there are human

beings.'

Aristotle and the Greeks

Heidegger was influenced at an early age by Aristotle, mediated through Catholic theology, medieval philosophy and Franz Brentano.

Aristotle's ethical, logical, and metaphysical works were crucial to

the development of his thought in the crucial period of the 1920s.

Although he later worked less on Aristotle, Heidegger recommended

postponing reading Nietzsche, and to "first study Aristotle for ten to

fifteen years".

In reading Aristotle, Heidegger increasingly contested the traditional

Latin translation and scholastic interpretation of his thought.

Particularly important (not least for its influence upon others, both in

their interpretation of Aristotle and in rehabilitating a

neo-Aristotelian "practical philosophy") was his radical reinterpretation of Book Six of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and several books of the Metaphysics. Both informed the argument of Being and Time.

Heidegger's thought is original in being an authentic retrieval of the

past, a repetition of the possibilities handed down by the tradition.

The idea of asking about being may be traced back via Aristotle to Parmenides. Heidegger claimed to have revived the question of being, the question having been largely forgotten by the metaphysical tradition extending from Plato to Descartes, a forgetfulness extending to the Age of Enlightenment

and then to modern science and technology. In pursuit of the retrieval

of this question, Heidegger spent considerable time reflecting on ancient Greek thought, in particular on Plato, Parmenides, Heraclitus, and Anaximander, as well as on the tragic playwright Sophocles.

Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey, the young Heidegger was influenced by Dilthey's works

Heidegger's very early project of developing a "hermeneutics of factical life" and his hermeneutical transformation of phenomenology was influenced in part by his reading of the works of Wilhelm Dilthey.

Of the influence of Dilthey, Hans-Georg Gadamer

writes the following: "As far as Dilthey is concerned, we all know

today what I have known for a long time: namely that it is a mistake to

conclude on the basis of the citation in Being and Time that

Dilthey was especially influential in the development of Heidegger's

thinking in the mid-1920s. This dating of the influence is much too

late." He adds that by the fall of 1923 it was plain that Heidegger felt

"the clear superiority of Count Yorck

over the famous scholar, Dilthey." Gadamer nevertheless makes clear

that Dilthey's influence was important in helping the youthful Heidegger

"in distancing himself from the systematic ideal of Neo-Kantianism, as

Heidegger acknowledges in Being and Time."

Based on Heidegger's earliest lecture courses, in which Heidegger

already engages Dilthey's thought prior to the period Gadamer mentions

as "too late", scholars as diverse as Theodore Kisiel and David Farrell Krell have argued for the importance of Diltheyan concepts and strategies in the formation of Heidegger's thought.

Even though Gadamer's interpretation of Heidegger has been

questioned, there is little doubt that Heidegger seized upon Dilthey's

concept of hermeneutics. Heidegger's novel ideas about ontology required

a gestalt formation, not merely a series of logical arguments,

in order to demonstrate his fundamentally new paradigm of thinking, and

the hermeneutic circle offered a new and powerful tool for the articulation and realization of these ideas.

Husserl

Edmund Husserl, the man who established the school of phenomenology

There is disagreement over the degree of influence that Edmund Husserl

had on Heidegger's philosophical development, just as there is

disagreement about the degree to which Heidegger's philosophy is

grounded in phenomenology.

These disagreements centre upon how much of Husserlian phenomenology is

contested by Heidegger, and how much this phenomenology in fact informs

Heidegger's own understanding.

On the relation between the two figures, Gadamer wrote: "When

asked about phenomenology, Husserl was quite right to answer as he used

to in the period directly after World War I: 'Phenomenology, that is me

and Heidegger'." Nevertheless, Gadamer noted that Heidegger was no

patient collaborator with Husserl, and that Heidegger's "rash ascent to

the top, the incomparable fascination he aroused, and his stormy

temperament surely must have made Husserl, the patient one, as

suspicious of Heidegger as he always had been of Max Scheler's volcanic fire."

Robert J. Dostal understood the importance of Husserl to be profound:

Heidegger himself, who is supposed to have broken with Husserl, bases his hermeneutics on an account of time that not only parallels Husserl's account in many ways but seems to have been arrived at through the same phenomenological method as was used by Husserl.... The differences between Husserl and Heidegger are significant, but if we do not see how much it is the case that Husserlian phenomenology provides the framework for Heidegger's approach, we will not be able to appreciate the exact nature of Heidegger's project in Being and Time or why he left it unfinished.

Daniel O. Dahlstrom saw Heidegger's presentation of his work as a

departure from Husserl as unfairly misrepresenting Husserl's own work.

Dahlstrom concluded his consideration of the relation between Heidegger

and Husserl as follows:

Heidegger's silence about the stark similarities between his account of temporality and Husserl's investigation of internal time-consciousness contributes to a misrepresentation of Husserl's account of intentionality. Contrary to the criticisms Heidegger advances in his lectures, intentionality (and, by implication, the meaning of 'to be') in the final analysis is not construed by Husserl as sheer presence (be it the presence of a fact or object, act or event). Yet for all its "dangerous closeness" to what Heidegger understands by temporality, Husserl's account of internal time-consciousness does differ fundamentally. In Husserl's account the structure of protentions is accorded neither the finitude nor the primacy that Heidegger claims are central to the original future of ecstatic-horizonal temporality.

Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard, considered to be the first existential philosopher

Heideggerians regarded Søren Kierkegaard as, by far, the greatest philosophical contributor to Heidegger's own existentialist concepts. Heidegger's concepts of anxiety (Angst)

and mortality draw on Kierkegaard and are indebted to the way in which

the latter lays out the importance of our subjective relation to truth,

our existence in the face of death, the temporality of existence, and

the importance of passionate affirmation of one's individual being-in-the-world.

Patricia J. Huntington claims that Heidegger's book Being and Time

continued Kierkegaard's existential goal. Nevertheless, she argues that

Heidegger began to distance himself from any existentialist thought.

Calvin Shrag argues Heidegger's early relationship with Kierkegaard as:

Kierkegaard is primarily concerned with existence as it is experienced in man's concrete ethico-religious situation. Heidegger is interested in deriving an ontological analysis of man. But as Heidegger's ontological and existentialist descriptions can arise only from ontic and existential experience, so Kierkegaard's ontic and existential elucidations express an implicit ontology.

Hölderlin and Nietzsche

Friedrich Hölderlin and Friedrich Nietzsche were both important influences on Heidegger,

and many of his lecture courses were devoted to one or the other,

especially in the 1930s and 1940s. The lectures on Nietzsche focused on

fragments posthumously published under the title The Will to Power, rather than on Nietzsche's published works. Heidegger read The Will to Power as the culminating expression of Western metaphysics, and the lectures are a kind of dialogue between the two thinkers.

The fundamental differences between the philosophical delineations of Heidegger and Adorno can be found in their contrasting views of Hölderlin's poetical works and to a lesser extent in their divergent views on German romanticism

in general. For Heidegger, Hölderlin expressed the intuitive necessity

of metaphysical concepts as a guide for ethical paradigms, devoid of

reflection. Adorno, on the other hand, pointed to the dialectic

reflection of historical situations, the sociological interpretations of

future outcomes, and therefore opposed the liberating principles of

intuitive concepts because they negatively surpassed the perception of

societal realities. Nevertheless, it was Heidegger's rationalization and later work on Hölderlin's poems as well as on Parmenides ("For to be aware and to be are the same," DK B 3) and his consistent understanding of Nietzsche's thought that formed the foundation of postmodern existentialism.

This is also the case for the lecture courses devoted to the

poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin, which became an increasingly central

focus of Heidegger's work and thought. Heidegger grants to Hölderlin a

singular place within the history of being and the history of Germany,

as a herald whose thought is yet to be "heard" in Germany or the West.

Many of Heidegger's works from the 1930s onwards include meditations on

lines from Hölderlin's poetry, and several of the lecture courses are

devoted to the reading of a single poem (see, for example, Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister").

Heidegger and Eastern thought

Some

writers on Heidegger's work see possibilities within it for dialogue

with traditions of thought outside of Western philosophy, particularly

East Asian thinking.

Despite perceived differences between Eastern and Western philosophy,

some of Heidegger's later work, particularly "A Dialogue on Language

between a Japanese and an Inquirer", does show an interest in initiating

such a dialogue. Heidegger himself had contact with a number of leading Japanese intellectuals, including members of the Kyoto School, notably Hajime Tanabe and Kuki Shūzō.

Reinhard May refers to Chang Chung-Yuan who stated "Heidegger is the

only Western Philosopher who not only intellectually understands Tao,

but has intuitively experienced the essence of it as well."

May sees great influence of Taoism and Japanese scholars in Heidegger's

work, although this influence is not acknowledged by the author. He

asserts: "The investigation concludes that Heidegger’s work was

significantly influenced by East Asian sources. It can be shown,

moreover, that in particular instances Heidegger even appropriated

wholesale and almost verbatim major ideas from the German translations

of Daoist and Zen Buddhist classics. This clandestine textual

appropriation of non-Western spirituality, the extent of which has gone

undiscovered for so long, seems quite unparalleled, with far-reaching

implications for our future interpretation of Heidegger’s work."

Islam

Heidegger has been influential in research on the relationship between Western philosophy and the history of ideas in Islam, particularly for some scholars interested in Arabic philosophical medieval sources. These include the Lebanese philosopher and architectural theorist Nader El-Bizri,

who, as well as focusing on the critique of the history of metaphysics

(as an 'Arab Heideggerian'), also moves towards rethinking the notion of

"dwelling" in the epoch of the modern unfolding of the essence of

technology and Gestell,

and realizing what can be described as a "confluence of Western and

Eastern thought" as well. El-Bizri has also taken a new direction in

his engagement in 'Heidegger Studies' by way of probing the

Arab/Levantine Anglophone reception of Sein und Zeit in 1937 as set in the Harvard doctoral thesis of the 20th century Lebanese thinker and diplomat Charles Malik.

It is also claimed that the works of counter-enlightenment philosophers such as Heidegger, along with Friedrich Nietzsche and Joseph de Maistre, influenced Iran's Shia Islamist scholars, notably Ali Shariati. A clearer impact of Heidegger in Iran is associated with thinkers such as Reza Davari Ardakani, Ahmad Fardid, and Fardid's student Jalal Al-e-Ahmad,

who have been closely associated with the unfolding of philosophical

thinking in a Muslim modern theological legacy in Iran. This included

the construction of the ideological foundations of the Iranian Revolution and modern political Islam in its connections with theology.

Heidegger and the Nazi Party

The rectorate

The University of Freiburg, where Heidegger was Rector from April 21, 1933, to April 23, 1934

Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Heidegger was elected rector of the University of Freiburg on April 21, 1933, and assumed the position the following day. On May 1, he joined the Nazi Party.

On 27 May 1933, Heidegger delivered his inaugural address, the Rektoratsrede ("The Self-assertion of the German University"), in a hall decorated with swastikas, with members of the Sturmabteilung and prominent Nazi Party officials present.

His tenure as rector was fraught with difficulties from the outset. Some Nazi

education officials viewed him as a rival, while others saw his efforts

as comical. Some of Heidegger's fellow Nazis also ridiculed his

philosophical writings as gibberish. He finally offered his resignation

as rector on 23 April 1934, and it was accepted on 27 April. Heidegger

remained a member of both the academic faculty and of the Nazi Party

until the end of the war.

Philosophical historian Hans Sluga wrote:

Though as rector he prevented students from displaying an anti-Semitic poster at the entrance to the university and from holding a book burning, he kept in close contact with the Nazi student leaders and clearly signaled to them his sympathy with their activism.

In 1945, Heidegger wrote of his term as rector, giving the writing to his son Hermann; it was published in 1983:

The rectorate was an attempt to see something in the movement that had come to power, beyond all its failings and crudeness, that was much more far-reaching and that could perhaps one day bring a concentration on the Germans' Western historical essence. It will in no way be denied that at the time I believed in such possibilities and for that reason renounced the actual vocation of thinking in favor of being effective in an official capacity. In no way will what was caused by my own inadequacy in office be played down. But these points of view do not capture what is essential and what moved me to accept the rectorate.

Treatment of Husserl

Beginning in 1917, German-Jewish philosopher Edmund Husserl championed Heidegger's work, and helped him secure the retiring Husserl's chair in Philosophy at the University of Freiburg.

On 6 April 1933, the Reichskommissar of Baden

Province, Robert Wagner, suspended all Jewish government employees,

including present and retired faculty at the University of Freiburg.

Heidegger's predecessor as Rector formally notified Husserl of his

"enforced leave of absence" on 14 April 1933.

Heidegger became Rector of the University of Freiburg on 22 April

1933. The following week the national Reich law of 28 April 1933

replaced Reichskommissar Wagner's decree. The Reich law required the

firing of Jewish professors from German universities, including those,

such as Husserl, who had converted to Christianity. The termination of

the retired professor Husserl's academic privileges thus did not involve

any specific action on Heidegger's part.

Heidegger had by then broken off contact with Husserl, other than

through intermediaries. Heidegger later claimed that his relationship

with Husserl had already become strained after Husserl publicly "settled

accounts" with Heidegger and Max Scheler in the early 1930s.

Heidegger did not attend his former mentor's cremation in 1938.

In 1941, under pressure from publisher Max Niemeyer, Heidegger agreed to

remove the dedication to Husserl from Being and Time (restored in post-war editions).

Heidegger's behavior towards Husserl has evoked controversy.

Arendt initially suggested that Heidegger's behavior precipitated

Husserl's death. She called Heidegger a "potential murderer." However,

she later recanted her accusation.

In 1939, only a year after Husserl's death, Heidegger wrote in his Black Notebooks:

"The more original and inceptive the coming decisions and questions

become, the more inaccessible will they remain to this [Jewish] 'race'.

Thus, Husserl’s step toward phenomenological observation, and his

rejection of psychological explanations and historiological reckoning of

opinions, are of enduring importance—yet it never reaches into the

domains of essential decisions", seeming to imply that Husserl's philosophy was limited purely because he was Jewish.

Post-rectorate period

After the failure of Heidegger's rectorship, he withdrew from most political activity, but remained a member of the Nazi Party.

In a 1935 lecture, later published in 1953 as part of the book Introduction to Metaphysics, Heidegger refers to the "inner truth and greatness" of the National Socialist movement (die innere Wahrheit und Größe dieser Bewegung),

but he then adds a qualifying statement in parentheses: "namely, the

confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity" (nämlich die Begegnung der planetarisch bestimmten Technik und des neuzeitlichen Menschen).

However, it subsequently transpired that this qualification had not

been made during the original lecture, although Heidegger claimed that

it had been. This has led scholars to argue that Heidegger still

supported the Nazi party in 1935 but that he did not want to admit this

after the war, and so he attempted to silently correct his earlier

statement.

In private notes written in 1939, Heidegger took a strongly critical view of Hitler's ideology;

however, in public lectures, he seems to have continued to make

ambiguous comments which, if they expressed criticism of the regime, did

so only in the context of praising its ideals. For instance, in a 1942

lecture, published posthumously, Heidegger said of recent German

classics scholarship:

In the majority of "research results," the Greeks appear as pure National Socialists. This overenthusiasm on the part of academics seems not even to notice that with such "results" it does National Socialism and its historical uniqueness no service at all, not that it needs this anyhow.

An important witness to Heidegger's continued allegiance to National

Socialism during the post-rectorship period is his former student Karl Löwith,

who met Heidegger in 1936 while Heidegger was visiting Rome. In an

account set down in 1940 (though not intended for publication), Löwith

recalled that Heidegger wore a swastika pin to their meeting, though

Heidegger knew that Löwith was Jewish. Löwith also recalled that

Heidegger "left no doubt about his faith in Hitler", and stated that his support for National Socialism was in agreement with the essence of his philosophy.

Heidegger rejected the "biologically grounded racism" of the Nazis, replacing it with linguistic-historical heritage.

Post-war period

After the end of World War II, Heidegger was summoned to appear at a denazification hearing. Heidegger's former lover Arendt spoke on his behalf at this hearing, while Jaspers spoke against him. He was charged on four counts, dismissed from the university and declared a "follower" (Mitläufer) of Nazism.

Heidegger was forbidden to teach between 1945 and 1951. One consequence

of this teaching ban was that Heidegger began to engage far more in the

French philosophical scene.

In his postwar thinking, Heidegger distanced himself from Nazism,

but his critical comments about Nazism seem "scandalous" to some since

they tend to equate the Nazi war atrocities with other inhumane

practices related to rationalisation and industrialisation, including the treatment of animals by factory farming.

For instance in a lecture delivered at Bremen in 1949, Heidegger said:

"Agriculture is now a motorized food industry, the same thing in its

essence as the production of corpses in the gas chambers and the

extermination camps, the same thing as blockades and the reduction of

countries to famine, the same thing as the manufacture of hydrogen

bombs."

In 1967 Heidegger met with the Jewish poet Paul Celan,

a concentration camp survivor. Celan visited Heidegger at his country

retreat and wrote an enigmatic poem about the meeting, which some

interpret as Celan's wish for Heidegger to apologize for his behavior

during the Nazi era.

Der Spiegel interview

On 23 September 1966, Heidegger was interviewed by Rudolf Augstein and Georg Wolff for Der Spiegel

magazine, in which he agreed to discuss his political past provided

that the interview be published posthumously. (It was published five

days after his death, on 31 May 1976.)

In the interview, Heidegger defended his entanglement with National

Socialism in two ways: first, he argued that there was no alternative,

saying that he was trying to save the university (and science in

general) from being politicized and thus had to compromise with the Nazi

administration. Second, he admitted that he saw an "awakening" (Aufbruch)

which might help to find a "new national and social approach," but said

that he changed his mind about this in 1934, largely prompted by the

violence of the Night of the Long Knives.

In his interview Heidegger defended as double-speak

his 1935 lecture describing the "inner truth and greatness of this

movement." He affirmed that Nazi informants who observed his lectures

would understand that by "movement" he meant National Socialism.

However, Heidegger asserted that his dedicated students would know this

statement was no eulogy for the Nazi Party. Rather, he meant it as he expressed it in the parenthetical clarification later added to Introduction to Metaphysics (1953), namely, "the confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity."

The eyewitness account of Löwith from 1940 contradicts the account given in the Der Spiegel

interview in two ways: that he did not make any decisive break with

National Socialism in 1934, and that Heidegger was willing to entertain

more profound relations between his philosophy and political

involvement. The Der Spiegel interviewers did not bring up

Heidegger's 1949 quotation comparing the industrialization of

agriculture to the extermination camps. In fact, the interviewers were

not in possession of much of the evidence now known for Heidegger's Nazi

sympathies. Der Spiegel journalist Georg Wolff had been an SS-Hauptsturmführer with the Sicherheitsdienst, stationed in Oslo during World War II, and had been writing articles with antisemitic and racist overtones in Der Spiegel since war's end.

Influence and reception in France

Heidegger

is "widely acknowledged to be one of the most original and important

philosophers of the 20th century while remaining one of the most

controversial."

His ideas have penetrated into many areas, but in France there is a

very long and particular history of reading and interpreting his work

which in itself resulted in deepening the impact of his thought in

Continental Philosophy. He influenced Jean Beaufret, François Fédier, Dominique Janicaud, Jean-Luc Marion, Jean-François Courtine and others.

Existentialism and pre-war influence

Heidegger's influence on French philosophy began in the 1930s, when Being and Time,

"What is Metaphysics?" and other Heideggerian texts were read by

Jean-Paul Sartre and other existentialists, as well as by thinkers such

as Alexandre Kojève, Georges Bataille and Emmanuel Levinas.

Because Heidegger's discussion of ontology (the study of being) is

rooted in an analysis of the mode of existence of individual human

beings (Da-sein, or there-being), his work has often been associated with existentialism. The influence of Heidegger on Sartre's Being and Nothingness (1943) is marked, but Heidegger felt that Sartre had misread his work, as he argued in later texts such as the "Letter on Humanism". In that text, intended for a French audience, Heidegger explained this misreading in the following terms:

Sartre's key proposition about the priority of existentia over essentia [that is, Sartre's statement that "existence precedes essence"] does, however, justify using the name "existentialism" as an appropriate title for a philosophy of this sort. But the basic tenet of "existentialism" has nothing at all in common with the statement from Being and Time [that "the 'essence' of Dasein lies in its existence"]—apart from the fact that in Being and Time no statement about the relation of essentia and existentia can yet be expressed, since there it is still a question of preparing something precursory.

"Letter on 'Humanism'" is often seen as a direct response to Sartre's 1945 lecture "Existentialism Is a Humanism".

Aside from merely disputing readings of his own work, however, in the

"Letter on Humanism" Heidegger asserts that "Every humanism is either

grounded in a metaphysics or is itself made to be the ground of one."

Heidegger's largest issue with Sartre's existential humanism is that,

while it does make a humanistic 'move' in privileging existence over

essence, "the reversal of a metaphysical statement remains a

metaphysical statement." From this point onward in his thought,

Heidegger attempted to think beyond metaphysics to a place where the

articulation of the fundamental questions of ontology were fundamentally

possible: only from this point can we restore (that is, re-give

[redonner]) any possible meaning to the word "humanism".

Post-war forays into France

After

the war, Heidegger was banned from university teaching for a period on

account of his support of Nazism while serving as Rector of Freiburg

University.

He developed a number of contacts in France, where his work continued

to be taught, and a number of French students visited him at Todtnauberg (see, for example, Jean-François Lyotard's brief account in Heidegger and "the Jews",

which discusses a Franco-German conference held in Freiburg in 1947,

one step toward bringing together French and German students).

Heidegger subsequently made several visits to France, and made efforts

to keep abreast of developments in French philosophy by way of

correspondence with Jean Beaufret, an early French translator of Heidegger, and with Lucien Braun.

Derrida and deconstruction

Deconstruction came to Heidegger's attention in 1967 by way of Lucien Braun's recommendation of Jacques Derrida's work (Hans-Georg Gadamer

was present at an initial discussion and indicated to Heidegger that

Derrida's work came to his attention by way of an assistant). Heidegger

expressed interest in meeting Derrida personally after the latter sent

him some of his work. There was discussion of a meeting in 1972, but

this failed to take place.

Heidegger's interest in Derrida is said by Braun to have been

considerable (as is evident in two letters, of September 29, 1967 and

May 16, 1972, from Heidegger to Braun). Braun also brought to

Heidegger's attention the work of Michel Foucault.

Foucault's relation to Heidegger is a matter of considerable

difficulty; Foucault acknowledged Heidegger as a philosopher whom he

read but never wrote about. (For more on this see Penser à Strasbourg,

Jacques Derrida, et al., which includes reproductions of both letters

and an account by Braun, "À mi-chemin entre Heidegger et Derrida").

Derrida attempted to displace the understanding of Heidegger's

work that had been prevalent in France from the period of the ban

against Heidegger teaching in German universities, which amounted to an

almost wholesale rejection of the influence of Jean-Paul Sartre

and existentialist terms. In Derrida's view, deconstruction is a

tradition inherited via Heidegger (the French term "déconstruction" is a

term coined to translate Heidegger's use of the words

"Destruktion"—literally "destruction"—and "Abbau"—more literally

"de-building"). According to Derrida, Sartre's interpretation of Dasein

and other key Heideggerian concerns is overly psychologistic,

anthropocentric, and misses the historicality central to Dasein in Being and Time.

The Farías debate

Jacques Derrida, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, and Jean-François Lyotard,

among others, all engaged in debate and disagreement about the relation

between Heidegger's philosophy and his Nazi politics. These debates

included the question of whether it was possible to do without

Heidegger's philosophy, a position which Derrida in particular rejected.

Forums where these debates took place include the proceedings of the

first conference dedicated to Derrida's work, published as "Les Fins de

l'homme à partir du travail de Jacques Derrida: colloque de Cerisy, 23

juillet-2 août 1980", Derrida's "Feu la cendre/cio' che resta del

fuoco", and the studies on Paul Celan by Lacoue-Labarthe and Derrida which shortly preceded the detailed studies of Heidegger's politics published in and after 1987.

When in 1987 Víctor Farías published his book Heidegger et le nazisme,

this debate was taken up by many others, some of whom were inclined to

disparage so-called "deconstructionists" for their association with

Heidegger's philosophy. Derrida and others not only continued to defend

the importance of reading Heidegger, but attacked Farías on the grounds

of poor scholarship and for what they saw as the sensationalism of his

approach. Not all scholars agreed with this negative assessment: Richard Rorty,

for example, declared that "[Farías'] book includes more concrete

information relevant to Heidegger's relations with the Nazis than

anything else available, and it is an excellent antidote to the evasive

apologetics that are still being published."

Bernard Stiegler

More recently, Heidegger's thought has influenced the work of the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler. This is evident even from the title of Stiegler's multi-volume magnum opus, La technique et le temps (volume one translated into English as Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus).

Stiegler offers an original reading of Heidegger, arguing that there

can be no access to "originary temporality" other than via material,

that is, technical, supports, and that Heidegger recognised this in the

form of his account of world historicality, yet in the end suppressed

that fact. Stiegler understands the existential analytic of Being and Time as an account of psychic individuation,

and his later "history of being" as an account of collective

individuation. He understands many of the problems of Heidegger's

philosophy and politics as the consequence of Heidegger's inability to

integrate the two.

Giorgio Agamben

Heidegger has been very influential on the work of the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben. Agamben attended seminars in France led by Heidegger in the late 1960s.

Criticism

Heidegger's influence upon 20th century continental philosophy is unquestioned and has produced a variety of critical responses.

Early criticisms

According to Husserl, Being and Time

claimed to deal with ontology but only did so in the first few pages of

the book. Having nothing further to contribute to an ontology

independent of human existence, Heidegger changed the topic to Dasein.

Whereas Heidegger argued that the question of human existence is

central to the pursuit of the question of being, Husserl criticized this

as reducing phenomenology to "philosophical anthropology" and offering

an abstract and incorrect portrait of the human being.

The Neo-Kantian Ernst Cassirer and Heidegger engaged in an influential debate located in Davos in 1929, concerning the significance of Kantian notions of freedom and rationality (see Cassirer–Heidegger debate). Whereas Cassirer defended the role of rationality in Kant, Heidegger argued for the priority of the imagination.

Dilthey's student Georg Misch wrote the first extended critical appropriation of Heidegger in Lebensphilosophie und Phänomenologie. Eine Auseinandersetzung der Diltheyschen Richtung mit Heidegger und Husserl, Leipzig 1930 (3rd ed. Stuttgart 1964).

The Young Hegelians and critical theory

Hegel-influenced Marxist thinkers, especially György Lukács and the Frankfurt School, associated the style and content of Heidegger's thought with German irrationalism and criticized its political implications.

Initially members of the Frankfurt School were positively

disposed to Heidegger, becoming more critical at the beginning of the

1930s. Heidegger's student Herbert Marcuse became associated with the

Frankfurt School. Initially striving for a synthesis between Hegelian

Marxism and Heidegger's phenomenology, Marcuse later rejected

Heidegger's thought for its "false concreteness" and "revolutionary

conservativism." Theodor Adorno wrote an extended critique of the ideological character of Heidegger's early and later use of language in the Jargon of Authenticity.

Contemporary social theorists associated with the Frankfurt School have

remained largely critical of Heidegger's works and influence. In

particular, Jürgen Habermas admonishes the influence of Heidegger on recent French philosophy in his polemic against "postmodernism" in The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity (1985). However, work by philosopher and critical theorist Nikolas Kompridis tries to show that Heidegger's insights into world disclosure

are badly misunderstood and mishandled by Habermas, and are of vital

importance for critical theory, offering an important way of renewing that tradition.

Reception by analytic and Anglo-American philosophy

Criticism of Heidegger's philosophy has also come from analytic philosophy, beginning with logical positivism. In "The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language" (1932), Rudolf Carnap accused Heidegger of offering an "illusory" ontology, criticizing him for committing the fallacy of reification

and for wrongly dismissing the logical treatment of language which,

according to Carnap, can only lead to writing "nonsensical

pseudo-propositions."

The British logical positivist A. J. Ayer

was strongly critical of Heidegger's philosophy. In Ayer's view,

Heidegger proposed vast, overarching theories regarding existence, which

are completely unverifiable through empirical demonstration and logical

analysis. For Ayer, this sort of philosophy was a poisonous strain in

modern thought. He considered Heidegger to be the worst example of such

philosophy, which Ayer believed to be entirely useless.

Bertrand Russell considered Heidegger an obscurantist, writing,

Highly eccentric in its terminology, his philosophy is extremely obscure. One cannot help suspecting that language is here running riot. An interesting point in his speculations is the insistence that nothingness is something positive. As with much else in Existentialism, this is a psychological observation made to pass for logic.

This quote expresses the sentiments of many 20th-century analytic philosophers concerning Heidegger.

Roger Scruton stated that: "His major work Being and Time

is formidably difficult—unless it is utter nonsense, in which case it

is laughably easy. I am not sure how to judge it, and have read no

commentator who even begins to make sense of it".

The analytic tradition values clarity of expression. Heidegger,

however, has on occasion appeared to take an opposing view, stating for

example:

those in the crossing must in the end know what is mistaken by all urging for intelligibility: that every thinking of being, all philosophy, can never be confirmed by "facts," i.e., by beings. Making itself intelligible is suicide for philosophy. Those who idolize "facts" never notice that their idols only shine in a borrowed light. They are also meant not to notice this; for thereupon they would have to be at a loss and therefore useless. But idolizers and idols are used wherever gods are in flight and so announce their nearness.

Apart from the charge of obscurantism,

other analytic philosophers considered the actual content of

Heidegger's work to be either faulty and meaningless, vapid or

uninteresting. However, not all analytic philosophers have been as

hostile. Gilbert Ryle wrote a critical yet positive review of Being and Time. Ludwig Wittgenstein made a remark recorded by Friedrich Waismann: "To be sure, I can imagine what Heidegger means by being and anxiety" which has been construed by some commentators

as sympathetic to Heidegger's philosophical approach. These positive

and negative analytic evaluations have been collected in Michael Murray

(ed.), Heidegger and Modern Philosophy: Critical Essays (Yale

University Press, 1978). Heidegger's reputation within English-language

philosophy has slightly improved in philosophical terms in some part

through the efforts of Hubert Dreyfus, Richard Rorty,

and a recent generation of analytically oriented phenomenology

scholars. Pragmatist Rorty claimed that Heidegger's approach to

philosophy in the first half of his career has much in common with that

of the latter-day Ludwig Wittgenstein. Nevertheless, Rorty asserted that

what Heidegger had constructed in his writings was a myth of being

rather than an account of it.

Contemporary European reception

Although Heidegger is considered by many observers to be one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, aspects of his work have been criticised by those who nevertheless acknowledge this influence, such as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jacques Derrida.

Some questions raised about Heidegger's philosophy include the priority

of ontology, the status of animals, the nature of the religious,

Heidegger's supposed neglect of ethics (Levinas), the body (Maurice Merleau-Ponty), sexual difference (Luce Irigaray), or space (Peter Sloterdijk).

Levinas was deeply influenced by Heidegger, and yet became one of

his fiercest critics, contrasting the infinity of the good beyond being

with the immanence and totality of ontology. Levinas also condemned

Heidegger's involvement with National Socialism, stating: "One can

forgive many Germans, but there are some Germans it is difficult to

forgive. It is difficult to forgive Heidegger."

Heidegger's defenders, notably Arendt, see his support for Nazism

as arguably a personal " 'error' " (a word which Arendt placed in

quotation marks when referring to Heidegger's Nazi-era politics). Defenders think this error was irrelevant to Heidegger's philosophy. Critics such as Levinas, Karl Löwith, and Theodor Adorno claim that Heidegger's support for National Socialism revealed flaws inherent in his thought.

Włodzimierz J. Korab-Karpowicz states in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

that Heidegger's writing is "notoriously difficult", possibly because

his thinking was "original" and clearly on obscure and innovative

topics. He concludes Being and Time "remains his most influential work."

In film

- Being in the World draws on Heidegger's work to explore what it means to be human in a technological age. A number of Heidegger scholars are interviewed, including Hubert Dreyfus, Mark Wrathall, Albert Borgmann, John Haugeland and Taylor Carman.

- The Ister (2004) is a film based on Heidegger's 1942 lecture course on Friedrich Hölderlin, and features Jean-Luc Nancy, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Bernard Stiegler, and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg.

- The film director Terrence Malick translated Heidegger's 1929 essay Vom Wesen des Grundes into English. It was published under the title The Essence of Reasons (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1969, bilingual edition). It is also frequently said of Malick that his cinema has Heideggerian sensibilities. See for instance: Marc Furstenau and Leslie MacAvoy, "Terrence Malick's Heideggerian Cinema: War and the Question of Being in The Thin Red Line" In The cinema of Terrence Malick: Poetic visions of America, 2nd ed. Edited by Hanna Patterson (London: Wallflower Press 2007): 179–91. See also: Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1979): XV.

- The 2006 experimental short Die Entnazifizierung des MH by James T. Hong imagines Heidegger's denazification proceedings.

- In the 2012 film Hannah Arendt, Heidegger is portrayed by actor Klaus Pohl.

Bibliography

Gesamtausgabe

Heidegger's collected works are published by Vittorio Klostermann. The Gesamtausgabe was begun during Heidegger's lifetime. He defined the order of

publication and dictated that the principle of editing should be "ways

not works." Publication has not yet been completed.

Selected works

| Year | Original German | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Sein und Zeit, Gesamtausgabe Volume 2 | Being and Time, trans. by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (London: SCM Press, 1962); re-translated by Joan Stambaugh (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996) |

| 1929 | Kant und das Problem der Metaphysik, Gesamtausgabe Volume 3 | Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, trans. by Richard Taft (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990) |

| 1935 | Einführung in die Metaphysik (1935, published 1953), Gesamtausgabe Volume 40 | Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. by Gregory Fried and Richard Polt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000) |

| 1936–8 | Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis) (1936–1938, published 1989), Gesamtausgabe Volume 65 | Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning), trans. by Parvis Emad and Kenneth Maly (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999); re-translated as Contributions to Philosophy (Of the Event), trans. by Richard Rojcewicz and Daniela Vallega-Neu (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012) |

| 1942 | Hölderlins Hymne »Der Ister« (1942, published 1984), Gesamtausgabe Volume 53 | Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister", trans. by William McNeill and Julia Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996) |

| 1949 | "Die Frage nach der Technik", in Gesamtausgabe Volume 7 | "The Question Concerning Technology", in Heidegger, Martin, Basic Writings: Second Edition, Revised and Expanded, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: Harper Collins, 1993) |

| 1950 | Holzwege, Gesamtausgabe Volume 5. This collection includes "Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes" (1935–1936) | Off the Beaten Track. This collection includes "The Origin of the Work of Art" |

| 1955–56 | Der Satz vom Grund, Gesamtausgabe Volume 10 | The Principle of Reason, trans. Reginald Lilly (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1991) |

| 1955–57 | Identität und Differenz, Gesamtausgabe Volume 11 | Identity and Difference, trans. by Joan Stambaugh (New York: Harper & Row, 1969) |

| 1959 | Gelassenheit, in Gesamtausgabe Volume 16 | Discourse On Thinking |

| 1959 | Unterwegs zur Sprache, Gesamtausgabe Volume 12 | On the Way To Language, published without the essay "Die Sprache" ("Language") by arrangement with Heidegger |