Mesopotamia (Ancient Greek: Μεσοποταμία Mesopotamíā; Arabic: بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن Bilād ar-Rāfidayn; Classical Syriac: ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, Ārām-Nahrīn or ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, Bēṯ Nahrīn) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Mesopotamia occupies most of present-day Iraq and Kuwait. The historical region includes the head of the Persian Gulf and parts of present-day Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

The Sumerians and Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians) dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire. It fell to Alexander the Great in 332 BC, and after his death, it became part of the Greek Seleucid Empire. Later the Arameans dominated major parts of Mesopotamia (c. 900 BC – 270 AD).

Around 150 BC, Mesopotamia was under the control of the Parthian Empire. Mesopotamia became a battleground between the Romans and Parthians, with western parts of Mesopotamia coming under ephemeral Roman control. In 226 AD, the eastern regions of Mesopotamia fell to the Sassanid Persians. The division of Mesopotamia between Roman (Byzantine from 395 AD) and Sassanid Empires lasted until the 7th century Muslim conquest of Persia of the Sasanian Empire and Muslim conquest of the Levant from Byzantines. A number of primarily neo-Assyrian and Christian native Mesopotamian states existed between the 1st century BC and 3rd century BC, including Adiabene, Osroene, and Hatra.

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture". It has been known as one of the earliest civilizations to ever exist in the world.

Etymology

The regional toponym Mesopotamia (/ˌmɛsəpəˈteɪmiə/, Ancient Greek: Μεσοποταμία '[land] between rivers'; Arabic: بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن Bilād ar-Rāfidayn

or بَيْن ٱلنَّهْرَيْن Bayn an-Nahrayn; Persian: میانرودان miyân rudân; Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ Beth Nahrain "land of rivers") comes from the ancient Greek root words μέσος (mesos, 'middle') and ποταμός (potamos, 'river') and translates to '(land) between rivers'. It is used throughout the Greek Septuagint (c. 250 BC) to translate the Hebrew and Aramaic equivalent Naharaim. An even earlier Greek usage of the name Mesopotamia is evident from The Anabasis of Alexander, which was written in the late 2nd century AD but specifically refers to sources from the time of Alexander the Great. In the Anabasis, Mesopotamia was used to designate the land east of the Euphrates in north Syria. The term Ārām Nahrīn (Classical Syriac: ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ) (Hebrew: ארם נהריים, Aram Naharayim) was used multiple times in the Old Testament of the Bible to describe "Aram between the (two) rivers".

The Aramaic term biritum/birit narim corresponded to a similar geographical concept. Later, the term Mesopotamia was more generally applied to all the lands between the Euphrates and the Tigris, thereby incorporating not only parts of Syria but also almost all of Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The neighbouring steppes to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the Zagros Mountains are also often included under the wider term Mesopotamia.

A further distinction is usually made between Northern or Upper Mesopotamia and Southern or Lower Mesopotamia. Upper Mesopotamia, also known as the Jazira, is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to Baghdad. Lower Mesopotamia is the area from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf and includes Kuwait and parts of western Iran.

In modern academic usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the Muslim conquests, with names like Syria, Jazira, and Iraq being used to describe the region after that date. It has been argued that these later euphemisms are Eurocentric terms attributed to the region in the midst of various 19th-century Western encroachments.

Geography

Mesopotamia encompasses the land between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, both of which have their headwaters in the Taurus Mountains. Both rivers are fed by numerous tributaries, and the entire river system drains a vast mountainous region. Overland routes in Mesopotamia usually follow the Euphrates because the banks of the Tigris are frequently steep and difficult. The climate of the region is semi-arid with a vast desert expanse in the north which gives way to a 15,000-square-kilometre (5,800 sq mi) region of marshes, lagoons, mudflats, and reed banks in the south. In the extreme south, the Euphrates and the Tigris unite and empty into the Persian Gulf.

The arid environment ranges from the northern areas of rain-fed agriculture to the south where irrigation of agriculture is essential if a surplus energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) is to be obtained. This irrigation is aided by a high water table and by melting snows from the high peaks of the northern Zagros Mountains and from the Armenian Highlands, the source of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that give the region its name. The usefulness of irrigation depends upon the ability to mobilize sufficient labor for the construction and maintenance of canals, and this, from the earliest period, has assisted the development of urban settlements and centralized systems of political authority.

Agriculture throughout the region has been supplemented by nomadic pastoralism, where tent-dwelling nomads herded sheep and goats (and later camels) from the river pastures in the dry summer months, out into seasonal grazing lands on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. The area is generally lacking in building stone, precious metals, and timber, and so historically has relied upon long-distance trade of agricultural products to secure these items from outlying areas. In the marshlands to the south of the area, a complex water-borne fishing culture has existed since prehistoric times and has added to the cultural mix.

Periodic breakdowns in the cultural system have occurred for a number of reasons. The demands for labor has from time to time led to population increases that push the limits of the ecological carrying capacity, and should a period of climatic instability ensue, collapsing central government and declining populations can occur. Alternatively, military vulnerability to invasion from marginal hill tribes or nomadic pastoralists has led to periods of trade collapse and neglect of irrigation systems. Equally, centripetal tendencies amongst city-states have meant that central authority over the whole region, when imposed, has tended to be ephemeral, and localism has fragmented power into tribal or smaller regional units. These trends have continued to the present day in Iraq.

History

The prehistory of the Ancient Near East begins in the Lower Paleolithic period. Therein, writing emerged with a pictographic script in the Uruk IV period (c. 4th millennium BC), and the documented record of actual historical events — and the ancient history of lower Mesopotamia — commenced in the mid-third millennium BC with cuneiform records of early dynastic kings. This entire history ends with either the arrival of the Achaemenid Empire in the late 6th century BC or with the Muslim conquest and the establishment of the Caliphate in the late 7th century AD, from which point the region came to be known as Iraq. In the long span of this period, Mesopotamia housed some of the world's most ancient highly developed, and socially complex states.

The region was one of the four riverine civilizations where writing was invented, along with the Nile valley in Ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization in the Indian subcontinent, and the Yellow River in Ancient China. Mesopotamia housed historically important cities such as Uruk, Nippur, Nineveh, Assur and Babylon, as well as major territorial states such as the city of Eridu, the Akkadian kingdoms, the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the various Assyrian empires. Some of the important historical Mesopotamian leaders were Ur-Nammu (king of Ur), Sargon of Akkad (who established the Akkadian Empire), Hammurabi (who established the Old Babylonian state), Ashur-uballit I and Tiglath-Pileser I (who established the Assyrian Empire).

Scientists analysed DNA from the 8,000-year-old remains of early farmers found at an ancient graveyard in Germany. They compared the genetic signatures to those of modern populations and found similarities with the DNA of people living in today's Turkey and Iraq.

Periodization

- Pre- and protohistory

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (10,000–8700 BC)

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (8700–6800 BC)

- Jarmo (7500–5000 BC)

- Hassuna (~6000 BC–? BC), Samarra (~5700–4900 BC) and Halaf cultures (~6000–5300 BC) cultures

- Ubaid period (~6500–4000 BC)

- Uruk period (~4000–3100 BC)

- Jemdet Nasr period (~3100–2900 BC)

- Early Bronze Age

- Early Dynastic period (~2900–2350 BC)

- Akkadian Empire (~2350–2100 BC)

- Third Dynasty of Ur (2112–2004 BC)

- Early Assyrian kingdom (24th to 18th century BC)

- Middle Bronze Age

- Isin-Larsa period (19th to 18th century BC)

- First Babylonian dynasty (18th to 17th century BC)

- Minoan eruption (c. 1620 BC)

- Late Bronze Age

- Old Assyrian period (16th to 11th century BC)

- Middle Assyrian period (c. 1365–1076 BC)

- Kassites in Babylon, (c. 1595–1155 BC)

- Late Bronze Age collapse (12th to 11th century BC)

- Iron Age

- Syro-Hittite states (11th to 7th century BC)

- Neo-Assyrian Empire (10th to 7th century BC)

- Neo-Babylonian Empire (7th to 6th century BC)

- Classical antiquity

- Persian Babylonia, Achaemenid Assyria (6th to 4th century BC)

- Seleucid Mesopotamia (4th to 3rd century BC)

- Parthian Babylonia (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD)

- Osroene (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD)

- Adiabene (1st to 2nd century AD)

- Hatra (1st to 2nd century AD)

- Roman Mesopotamia (2nd to 7th centuries AD), Roman Assyria (2nd century AD)

- Late Antiquity

- Palmyrene Empire (3nd century AD)

- Asōristān (3rd to 7th century AD)

- Euphratensis (mid-4th century AD to 7th century AD)

- Muslim conquest (mid-7th century AD)

Language and writing

The earliest language written in Mesopotamia was Sumerian, an agglutinative language isolate. Along with Sumerian, Semitic languages were also spoken in early Mesopotamia. Subartuan, a language of the Zagros possibly related to the Hurro-Urartuan language family, is attested in personal names, rivers and mountains and in various crafts. Akkadian came to be the dominant language during the Akkadian Empire and the Assyrian empires, but Sumerian was retained for administrative, religious, literary and scientific purposes. Different varieties of Akkadian were used until the end of the Neo-Babylonian period. Old Aramaic, which had already become common in Mesopotamia, then became the official provincial administration language of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and then the Achaemenid Empire: the official lect is called Imperial Aramaic. Akkadian fell into disuse, but both it and Sumerian were still used in temples for some centuries. The last Akkadian texts date from the late 1st century AD.

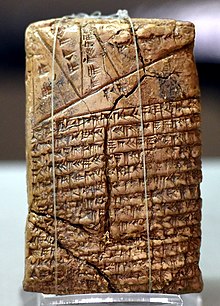

Early in Mesopotamia's history (around the mid-4th millennium BC) cuneiform was invented for the Sumerian language. Cuneiform literally means "wedge-shaped", due to the triangular tip of the stylus used for impressing signs on wet clay. The standardized form of each cuneiform sign appears to have been developed from pictograms. The earliest texts (7 archaic tablets) come from the É, a temple dedicated to the goddess Inanna at Uruk, from a building labeled as Temple C by its excavators.

The early logographic system of cuneiform script took many years to master. Thus, only a limited number of individuals were hired as scribes to be trained in its use. It was not until the widespread use of a syllabic script was adopted under Sargon's rule that significant portions of the Mesopotamian population became literate. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools, through which literacy was disseminated.

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate), but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD.

Literature

Libraries were extant in towns and temples during the Babylonian Empire. An old Sumerian proverb averred that "he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn." Women as well as men learned to read and write, and for the Semitic Babylonians, this involved knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, and a complicated and extensive syllabary.

A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were all arranged and named, and elaborate lists were drawn up.

Many Babylonian literary works are still studied today. One of the most famous of these was the Epic of Gilgamesh, in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certain Sîn-lēqi-unninni, and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career of Gilgamesh. The whole story is a composite product, although it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure.

Science and technology

Mathematics

Mesopotamian mathematics and science was based on a sexagesimal (base 60) numeral system. This is the source of the 60-minute hour, the 24-hour day, and the 360-degree circle. The Sumerian calendar was lunisolar, with three seven-day weeks of a lunar month. This form of mathematics was instrumental in early map-making. The Babylonians also had theorems on how to measure the area of several shapes and solids. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if π were fixed at 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the area of the base and the height; however, the volume of the frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used π as 25/8 (3.125 instead of 3.14159~). The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven modern miles (11 km). This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time.

Astronomy

From Sumerian times, temple priesthoods had attempted to associate current events with certain positions of the planets and stars. This continued to Assyrian times, when Limmu lists were created as a year by year association of events with planetary positions, which, when they have survived to the present day, allow accurate associations of relative with absolute dating for establishing the history of Mesopotamia.

The Babylonian astronomers were very adept at mathematics and could predict eclipses and solstices. Scholars thought that everything had some purpose in astronomy. Most of these related to religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers worked out a 12-month calendar based on the cycles of the moon. They divided the year into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy as well as astrology date from this time.

During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began studying philosophy dealing with the ideal nature of the early universe and began employing an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution. This new approach to astronomy was adopted and further developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy.

In Seleucid and Parthian times, the astronomical reports were thoroughly scientific; how much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered to be a major episode in the history of astronomy.

The only Greek-Babylonian astronomer known to have supported a heliocentric model of planetary motion was Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BC). Seleucus is known from the writings of Plutarch. He supported Aristarchus of Samos' heliocentric theory where the Earth rotated around its own axis which in turn revolved around the Sun. According to Plutarch, Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used (except that he correctly theorized on tides as a result of Moon's attraction).

Babylonian astronomy served as the basis for much of Greek, classical Indian, Sassanian, Byzantine, Syrian, medieval Islamic, Central Asian, and Western European astronomy.

Medicine

The oldest Babylonian texts on medicine date back to the Old Babylonian period in the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is the Diagnostic Handbook written by the ummânū, or chief scholar, Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa, during the reign of the Babylonian king Adad-apla-iddina (1069-1046 BC).

Along with contemporary Egyptian medicine, the Babylonians introduced the concepts of diagnosis, prognosis, physical examination, enemas, and prescriptions. In addition, the Diagnostic Handbook introduced the methods of therapy and aetiology and the use of empiricism, logic, and rationality in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. The text contains a list of medical symptoms and often detailed empirical observations along with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of a patient with its diagnosis and prognosis.

The symptoms and diseases of a patient were treated through therapeutic means such as bandages, creams and pills. If a patient could not be cured physically, the Babylonian physicians often relied on exorcism to cleanse the patient from any curses. Esagil-kin-apli's Diagnostic Handbook was based on a logical set of axioms and assumptions, including the modern view that through the examination and inspection of the symptoms of a patient, it is possible to determine the patient's disease, its aetiology, its future development, and the chances of the patient's recovery.

Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of illnesses and diseases and described their symptoms in his Diagnostic Handbook. These include the symptoms for many varieties of epilepsy and related ailments along with their diagnosis and prognosis.

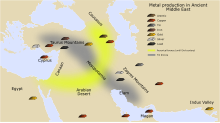

Technology

Mesopotamian people invented many technologies including metal and copper-working, glass and lamp making, textile weaving, flood control, water storage, and irrigation. They were also one of the first Bronze Age societies in the world. They developed from copper, bronze, and gold on to iron. Palaces were decorated with hundreds of kilograms of these very expensive metals. Also, copper, bronze, and iron were used for armor as well as for different weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, and maces.

According to a recent hypothesis, the Archimedes' screw may have been used by Sennacherib, King of Assyria, for the water systems at the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and Nineveh in the 7th century BC, although mainstream scholarship holds it to be a Greek invention of later times. Later, during the Parthian or Sasanian periods, the Baghdad Battery, which may have been the world's first battery, was created in Mesopotamia.

Religion and philosophy

The Ancient Mesopotamian religion was the first recorded. Mesopotamians believed that the world was a flat disc, surrounded by a huge, holed space, and above that, heaven. They also believed that water was everywhere, the top, bottom and sides, and that the universe was born from this enormous sea. In addition, Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic. Although the beliefs described above were held in common among Mesopotamians, there were also regional variations. The Sumerian word for universe is an-ki, which refers to the god An and the goddess Ki. Their son was Enlil, the air god. They believed that Enlil was the most powerful god. He was the chief god of the pantheon.

Philosophy

The numerous civilizations of the area influenced the Abrahamic religions, especially the Hebrew Bible; its cultural values and literary influence are especially evident in the Book of Genesis.

Giorgio Buccellati believes that the origins of philosophy can be traced back to early Mesopotamian wisdom, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the forms of dialectic, dialogues, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, prose works, and proverbs. Babylonian reason and rationality developed beyond empirical observation.

The earliest form of logic was developed by the Babylonians, notably in the rigorous nonergodic nature of their social systems. Babylonian thought was axiomatic and is comparable to the "ordinary logic" described by John Maynard Keynes. Babylonian thought was also based on an open-systems ontology which is compatible with ergodic axioms. Logic was employed to some extent in Babylonian astronomy and medicine.

Babylonian thought had a considerable influence on early Ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy. In particular, the Babylonian text Dialogue of Pessimism contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the Sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of dialectic, and the dialogs of Plato, as well as a precursor to the Socratic method. The Ionian philosopher Thales was influenced by Babylonian cosmological ideas.

Culture

Festivals

Ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies each month. The theme of the rituals and festivals for each month was determined by at least six important factors:

- The Lunar phase (a waxing moon meant abundance and growth, while a waning moon was associated with decline, conservation, and festivals of the Underworld)

- The phase of the annual agricultural cycle

- Equinoxes and solstices

- The local mythos and its divine Patrons

- The success of the reigning Monarch

- The Akitu, or New Year Festival (first full moon after spring equinox)

- Commemoration of specific historical events (founding, military victories, temple holidays, etc.)

Music

Some songs were written for the gods but many were written to describe important events. Although music and songs amused kings, they were also enjoyed by ordinary people who liked to sing and dance in their homes or in the marketplaces. Songs were sung to children who passed them on to their children. Thus songs were passed on through many generations as an oral tradition until writing was more universal. These songs provided a means of passing on through the centuries highly important information about historical events.

The Oud (Arabic:العود) is a small, stringed musical instrument used by the Mesopotamians. The oldest pictorial record of the Oud dates back to the Uruk period in Southern Mesopotamia over 5000 years ago. It is on a cylinder seal currently housed at the British Museum and acquired by Dr. Dominique Collon. The image depicts a female crouching with her instruments upon a boat, playing right-handed. This instrument appears hundreds of times throughout Mesopotamian history and again in ancient Egypt from the 18th dynasty onwards in long- and short-neck varieties. The oud is regarded as a precursor to the European lute. Its name is derived from the Arabic word العود al-‘ūd 'the wood', which is probably the name of the tree from which the oud was made. (The Arabic name, with the definite article, is the source of the word 'lute'.)

Games

Hunting was popular among Assyrian kings. Boxing and wrestling feature frequently in art, and some form of polo was probably popular, with men sitting on the shoulders of other men rather than on horses. They also played majore, a game similar to the sport rugby, but played with a ball made of wood. They also played a board game similar to senet and backgammon, now known as the "Royal Game of Ur".

Family life

Mesopotamia, as shown by successive law codes, those of Urukagina, Lipit Ishtar and Hammurabi, across its history became more and more a patriarchal society, one in which the men were far more powerful than the women. For example, during the earliest Sumerian period, the "en", or high priest of male gods was originally a woman, that of female goddesses, a man. Thorkild Jacobsen, as well as many others, has suggested that early Mesopotamian society was ruled by a "council of elders" in which men and women were equally represented, but that over time, as the status of women fell, that of men increased. As for schooling, only royal offspring and sons of the rich and professionals, such as scribes, physicians, temple administrators, went to school. Most boys were taught their father's trade or were apprenticed out to learn a trade. Girls had to stay home with their mothers to learn housekeeping and cooking, and to look after the younger children. Some children would help with crushing grain or cleaning birds. Unusually for that time in history, women in Mesopotamia had rights. They could own property and, if they had good reason, get a divorce.

Burials

Hundreds of graves have been excavated in parts of Mesopotamia, revealing information about Mesopotamian burial habits. In the city of Ur, most people were buried in family graves under their houses, along with some possessions. A few have been found wrapped in mats and carpets. Deceased children were put in big "jars" which were placed in the family chapel. Other remains have been found buried in common city graveyards. 17 graves have been found with very precious objects in them. It is assumed that these were royal graves. Rich of various periods, have been discovered to have sought burial in Bahrein, identified with Sumerian Dilmun.

Economy

Sumerian temples functioned as banks and developed the first large-scale system of loans and credit, but the Babylonians developed the earliest system of commercial banking. It was comparable in some ways to modern post-Keynesian economics, but with a more "anything goes" approach.

Agriculture

Irrigated agriculture spread southwards from the Zagros foothills with the Samara and Hadji Muhammed culture, from about 5,000 BC.

In the early period down to Ur III temples owned up to one third of the available land, declining over time as royal and other private holdings increased in frequency. The word Ensi was used to describe the official who organized the work of all facets of temple agriculture. Villeins are known to have worked most frequently within agriculture, especially in the grounds of temples or palaces.

The geography of southern Mesopotamia is such that agriculture is possible only with irrigation and with good drainage, a fact which had a profound effect on the evolution of early Mesopotamian civilization. The need for irrigation led the Sumerians, and later the Akkadians, to build their cities along the Tigris and Euphrates and the branches of these rivers. Major cities, such as Ur and Uruk, took root on tributaries of the Euphrates, while others, notably Lagash, were built on branches of the Tigris. The rivers provided the further benefits of fish (used both for food and fertilizer), reeds, and clay (for building materials). With irrigation, the food supply in Mesopotamia was comparable to that of the Canadian prairies.

The Tigris and Euphrates River valleys form the northeastern portion of the Fertile Crescent, which also included the Jordan River valley and that of the Nile. Although land nearer to the rivers was fertile and good for crops, portions of land farther from the water were dry and largely uninhabitable. Thus the development of irrigation became very important for settlers of Mesopotamia. Other Mesopotamian innovations include the control of water by dams and the use of aqueducts. Early settlers of fertile land in Mesopotamia used wooden plows to soften the soil before planting crops such as barley, onions, grapes, turnips, and apples. Mesopotamian settlers were some of the first people to make beer and wine. As a result of the skill involved in farming in the Mesopotamian region, farmers did not generally depend on slaves to complete farm work for them, but there were some exceptions. There were too many risks involved to make slavery practical (i.e. the escape/mutiny of the slaves). Although the rivers sustained life, they also destroyed it by frequent floods that ravaged entire cities. The unpredictable Mesopotamian weather was often hard on farmers; crops were often ruined so backup sources of food such as cows and lambs were also kept. Over time the southernmost parts of Sumerian Mesopotamia suffered from increased salinity of the soils, leading to a slow urban decline and a centring of power in Akkad, further north.

Trade

Mesopotamian trade with the Indus Valley civilisation flourished as early as the third millennium BC. Starting in the 4th millennium BC, Mesopotamian civilizations also traded with ancient Egypt (see Egypt–Mesopotamia relations).

For much of history, Mesopotamia served as a trade nexus - east-west between Central Asia and the Mediterranean world (part of the Silk Road), as well as north–south between the Eastern Europe and Baghdad (Volga trade route). Vasco da Gama's pioneering (1497-1499) of the sea route between India and Europe and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 impacted on this nexus.

Government

The geography of Mesopotamia had a profound impact on the political development of the region. Among the rivers and streams, the Sumerian people built the first cities along with irrigation canals which were separated by vast stretches of open desert or swamp where nomadic tribes roamed. Communication among the isolated cities was difficult and, at times, dangerous. Thus, each Sumerian city became a city-state, independent of the others and protective of its independence. At times one city would try to conquer and unify the region, but such efforts were resisted and failed for centuries. As a result, the political history of Sumer is one of almost constant warfare. Eventually Sumer was unified by Eannatum, but the unification was tenuous and failed to last as the Akkadians conquered Sumer in 2331 BC only a generation later. The Akkadian Empire was the first successful empire to last beyond a generation and see the peaceful succession of kings. The empire was relatively short-lived, as the Babylonians conquered them within only a few generations.

Kings

The Mesopotamians believed their kings and queens were descended from the City of Gods, but, unlike the ancient Egyptians, they never believed their kings were real gods. Most kings named themselves "king of the universe" or "great king". Another common name was "shepherd", as kings had to look after their people.

Power

When Assyria grew into an empire, it was divided into smaller parts, called provinces. Each of these were named after their main cities, like Nineveh, Samaria, Damascus, and Arpad. They all had their own governor who had to make sure everyone paid their taxes. Governors also had to call up soldiers to war and supply workers when a temple was built. He was also responsible for enforcing the laws. In this way, it was easier to keep control of a large empire. Although Babylon was quite a small state in Sumer, it grew tremendously throughout the time of Hammurabi's rule. He was known as "the lawmaker" and created the Code of Hammurabi, and soon Babylon became one of the main cities in Mesopotamia. It was later called Babylonia, which meant "the gateway of the gods." It also became one of history's greatest centers of learning.

Warfare

With the end of the Uruk phase, walled cities grew and many isolated Ubaid villages were abandoned indicating a rise in communal violence. An early king Lugalbanda was supposed to have built the white walls around the city. As city-states began to grow, their spheres of influence overlapped, creating arguments between other city-states, especially over land and canals. These arguments were recorded in tablets several hundreds of years before any major war—the first recording of a war occurred around 3200 BC but was not common until about 2500 BC. An Early Dynastic II king (Ensi) of Uruk in Sumer, Gilgamesh (c. 2600 BC), was commended for military exploits against Humbaba guardian of the Cedar Mountain, and was later celebrated in many later poems and songs in which he was claimed to be two-thirds god and only one-third human. The later Stele of the Vultures at the end of the Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 BC), commemorating the victory of Eannatum of Lagash over the neighbouring rival city of Umma is the oldest monument in the world that celebrates a massacre. From this point forwards, warfare was incorporated into the Mesopotamian political system. At times a neutral city may act as an arbitrator for the two rival cities. This helped to form unions between cities, leading to regional states. When empires were created, they went to war more with foreign countries. King Sargon, for example, conquered all the cities of Sumer, some cities in Mari, and then went to war with northern Syria. Many Assyrian and Babylonian palace walls were decorated with the pictures of the successful fights and the enemy either desperately escaping or hiding amongst reeds.

Laws

City-states of Mesopotamia created the first law codes, drawn from legal precedence and decisions made by kings. The codes of Urukagina and Lipit Ishtar have been found. The most renowned of these was that of Hammurabi, as mentioned above, who was posthumously famous for his set of laws, the Code of Hammurabi (created c. 1780 BC), which is one of the earliest sets of laws found and one of the best preserved examples of this type of document from ancient Mesopotamia. He codified over 200 laws for Mesopotamia. Examination of the laws show a progressive weakening of the rights of women, and increasing severity in the treatment of slaves.

Art

The art of Mesopotamia rivalled that of Ancient Egypt as the most grand, sophisticated and elaborate in western Eurasia from the 4th millennium BC until the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered the region in the 6th century BC. The main emphasis was on various, very durable, forms of sculpture in stone and clay; little painting has survived, but what has suggests that painting was mainly used for geometrical and plant-based decorative schemes, though most sculpture was also painted.

The Protoliterate period, dominated by Uruk, saw the production of sophisticated works like the Warka Vase and cylinder seals. The Guennol Lioness is an outstanding small limestone figure from Elam of about 3000–2800 BC, part man and part lion. A little later there are a number of figures of large-eyed priests and worshippers, mostly in alabaster and up to a foot high, who attended temple cult images of the deity, but very few of these have survived. Sculptures from the Sumerian and Akkadian period generally had large, staring eyes, and long beards on the men. Many masterpieces have also been found at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (c. 2650 BC), including the two figures of a Ram in a Thicket, the Copper Bull and a bull's head on one of the Lyres of Ur.

From the many subsequent periods before the ascendency of the Neo-Assyrian Empire Mesopotamian art survives in a number of forms: cylinder seals, relatively small figures in the round, and reliefs of various sizes, including cheap plaques of moulded pottery for the home, some religious and some apparently not. The Burney Relief is an unusual elaborate and relatively large (20 x 15 inches) terracotta plaque of a naked winged goddess with the feet of a bird of prey, and attendant owls and lions. It comes from the 18th or 19th centuries BC, and may also be moulded. Stone stelae, votive offerings, or ones probably commemorating victories and showing feasts, are also found from temples, which unlike more official ones lack inscriptions that would explain them; the fragmentary Stele of the Vultures is an early example of the inscribed type, and the Assyrian Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III a large and solid late one.

The conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia and much surrounding territory by the Assyrians created a larger and wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendour of the art of the neighbouring Egyptian empire. The Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone for palaces, with scenes of war or hunting; the British Museum has an outstanding collection. They produced very little sculpture in the round, except for colossal guardian figures, often the human-headed lamassu, which are sculpted in high relief on two sides of a rectangular block, with the heads effectively in the round (and also five legs, so that both views seem complete). Even before dominating the region they had continued the cylinder seal tradition with designs which are often exceptionally energetic and refined.

Architecture

The study of ancient Mesopotamian architecture is based on available archaeological evidence, pictorial representation of buildings, and texts on building practices. Scholarly literature usually concentrates on temples, palaces, city walls and gates, and other monumental buildings, but occasionally one finds works on residential architecture as well. Archaeological surface surveys also allowed for the study of urban form in early Mesopotamian cities.

Brick is the dominant material, as the material was freely available locally, whereas building stone had to be brought a considerable distance to most cities. The ziggurat is the most distinctive form, and cities often had large gateways, of which the Ishtar Gate from Neo-Babylonian Babylon, decorated with beasts in polychrome brick, is the most famous, now largely in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

The most notable architectural remains from early Mesopotamia are the temple complexes at Uruk from the 4th millennium BC, temples and palaces from the Early Dynastic period sites in the Diyala River valley such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar, the Third Dynasty of Ur remains at Nippur (Sanctuary of Enlil) and Ur (Sanctuary of Nanna), Middle Bronze Age remains at Syrian-Turkish sites of Ebla, Mari, Alalakh, Aleppo and Kultepe, Late Bronze Age palaces at Hattusa, Ugarit, Ashur and Nuzi, Iron Age palaces and temples at Assyrian (Kalhu/Nimrud, Khorsabad, Nineveh), Babylonian (Babylon), Urartian (Tushpa/Van, Kalesi, Cavustepe, Ayanis, Armavir, Erebuni, Bastam) and Neo-Hittite sites (Karkamis, Tell Halaf, Karatepe). Houses are mostly known from Old Babylonian remains at Nippur and Ur. Among the textual sources on building construction and associated rituals are Gudea's cylinders from the late 3rd millennium are notable, as well as the Assyrian and Babylonian royal inscriptions from the Iron Age.