| Slavery |

|---|

|

|

|

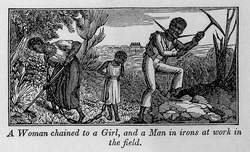

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

The debate over slave treatment

In the decades before the American Civil War, defenders of slavery often argued that slavery was a positive good, both for the enslavers and the enslaved people. They defended the legal enslavement of people for their labor as a benevolent, paternalistic institution with social and economic benefits, an important bulwark of civilization, and a divine institution similar or superior to the free labor in the North.

Some slavery advocates asserted that many slaves were content with their situation. African-American abolitionist J. Sella Martin countered that apparent "contentment" was in fact a psychological defense to dehumanizing brutality of having to bear witness to their spouses being sold at auction and daughters raped.

After Civil War and emancipation, White Southerners developed the pseudohistorical Lost Cause mythology in order to justify White supremacy and segregation. This mythology deeply influenced the mindset of White Southerners, influencing textbooks well into the 1970s. One of its tenets was the myth of the faithful slave. In reality, the enslaved people "desperately sought freedom". While 180,000 African-American soldiers fought in the United States Army during the Civil War, no slave fought as a soldier for the Confederacy.

Legal regulations

Legal regulations of slavery were called slave codes. In the territories and states established after the United States became independent, these slave codes were designed by the politically dominant planter class in order to make "the region safe for slavery".

In North Carolina, slaves were entitled to be clothed and fed, and murder of a slave was punishable. But slaves could not give testimony against whites nor could they initiate legal actions. There was no protection against rape. "The entire system worked against protection of slave women from sexual assault and violence".

Living conditions

Compiling a variety of historical sources, historian Kenneth M. Stampp identified in his classic work The Peculiar Institution reoccurring themes in slavemasters’ efforts to produce the "ideal slave":

- Maintain strict discipline and unconditional submission.

- Create a sense of personal inferiority, so that slaves "know their place."

- Instill fear.

- Teach servants to take interest in their master's enterprise.

- Prevent access to education and recreation, to ensure that slaves remain uneducated, helpless, and dependent.

Punishment and abuse

Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding, rape, and imprisonment. Punishment was often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was performed to re-assert the dominance of the master (or overseer) over the slave.

Pregnancy was not a barrier to punishment; methods were devised to administer lashings without harming the baby. Slave masters would dig a hole big enough for the woman's stomach to lie in and proceed with the lashings.

Slave overseers were authorized to whip and punish slaves. One overseer told a visitor, "Some Negroes are determined never to let a white man whip them and will resist you, when you attempt it; of course you must kill them in that case." A former slave describes witnessing females being whipped: "They usually screamed and prayed, though a few never made a sound."

In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass describes the cowskin whip:

The cowskin ... is made entirely of untanned, but dried, ox hide, and is about as hard as a piece of well-seasoned live oak. It is made of various sizes, but the usual length is about three feet. The part held in the hand is nearly an inch in thickness; and, from the extreme end of the butt or handle, the cowskin tapers its whole length to a point. This makes it quite elastic and springy. A blow with it, on the hardest back, will gash the flesh, and make the blood start. Cowskins are painted red, blue and green, and are the favorite slave whip. I think this whip worse than the "cat-o'nine-tails." It condenses the whole strength of the arm to a single point, and comes with a spring that makes the air whistle. It is a terrible instrument, and is so handy, that the overseer can always have it on his person, and ready for use. The temptation to use it is ever strong; and an overseer can, if disposed, always have cause for using it.

The results of harsh punishments are sometimes mentioned in newspaper ads describing runaway slaves. One ad describes a woman of about 18 years, named Patty: “Her back appears to have been used to the whip."

A metal collar could be put on a slave. Such collars were thick and heavy; they often had protruding spikes which impeded work as well as rest. Louis Cain, a survivor of slavery, described the punishment of a fellow slave: "One nigger run to the woods to be a jungle nigger, but massa cotched him with the dog and took a hot iron and brands him. Then he put a bell on him, in a wooden frame what slip over the shoulders and under the arms. He made that nigger wear the bell a year and took it off on Christmas for a present to him. It sho' did make a good nigger out of him."

The branding of slaves for identification was common during the colonial era; however, by the nineteenth century it was used primarily as punishment. Mutilation of slaves, such as castration of males, removing a front tooth or teeth, and amputation of ears was a relatively common punishment during the colonial era, still used in 1830: it facilitated their identification if they ran away. Any punishment was permitted for runaway slaves, and many bore wounds from shotgun blasts or dog bites inflicted by their captors.

Slaves were punished for a number of reasons: working too slowly, breaking a law (for example, running away), leaving the plantation without permission, insubordination, impudence as defined by the owner or overseer, or for no reason, to underscore a threat or to assert the owner's dominance and masculinity. Myers and Massy describe the practices: "The punishment of deviant slaves was decentralized, based on plantations, and crafted so as not to impede their value as laborers." Whites punished slaves publicly to set an example. A man named Harding describes an incident in which a woman assisted several men in a minor rebellion: "The women he hoisted up by the thumbs, whipp'd and slashed her [sic] with knives before the other slaves till she died." Men and women were sometimes punished differently; according to the 1789 report of the Virginia Committee of the Privy Council, males were often shackled but women and girls were left free.

Wilma Dunaway notes that slaves were often punished for their failure to demonstrate due deference and submission to whites. Demonstrating politeness and humility showed the slave was submitting to the established racial and social order, while failure to follow them demonstrated insolence and a threat to the social hierarchy. Dunway observes that slaves were punished almost as often for symbolic violations of the social order as they were for physical failures; in Appalachia, two-thirds of whippings were done for social offences versus one-third for physical offences such as low productivity or property losses.

Education and access to information

Slave owners greatly feared slave rebellions. Most of them sought to minimize slaves' exposure to the outside world to reduce the risk. The desired result was to eliminate slaves' dreams and aspirations, restrict access to information about escaped slaves and rebellions, and stifle their mental faculties.

Teaching slaves to read was discouraged or (depending upon the state) prohibited, so as to hinder aspirations for escape or rebellion. Slaveowners believed slaves with knowledge would become morose, if not insolent and "uppity". They might learn of the Underground Railroad: that escape was possible, that many would help, and that there were sizeable communities of formerly enslaved Blacks in Northern cities. In response to slave rebellions such as the Haitian Revolution, the 1811 German Coast Uprising, a failed uprising in 1822 organized by Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, some states prohibited slaves from holding religious gatherings, or any other kind of gathering, without a white person present, for fear that such meetings could facilitate communication and lead to rebellion and escapes.

In 1841, Virginia punished violations of this law by 20 lashes to the slave and a $100 fine to the teacher, and North Carolina by 39 lashes to the slave and a $250 fine to the teacher. In Kentucky, education of slaves was legal but almost nonexistent. Some Missouri slaveholders educated their slaves or permitted them to do so themselves.

Medical treatment

The quality of medical care to slaves is uncertain; some historians conclude that because slaveholders wished to preserve the value of their slaves, they received the same care as whites did. Others conclude that medical care was poor. A majority of plantation owners and doctors balanced a plantation need to coerce as much labor as possible from a slave without causing death, infertility, or a reduction in productivity; the effort by planters and doctors to provide sufficient living resources that enabled their slaves to remain productive and bear many children; the impact of diseases and injury on the social stability of slave communities; the extent to which illness and mortality of sub-populations in slave society reflected their different environmental exposures and living circumstances rather than their alleged racial characteristics. Slaves may have also provided adequate medical care to each other.

According to Michael W. Byrd, a dual system of medical care provided poorer care for slaves throughout the South, and slaves were excluded from proper, formal medical training. This meant that slaves were mainly responsible for their own care, a "health subsystem" that persisted long after slavery was abolished.

Medical care was usually provided by fellow slaves or by slaveholders and their families, and only rarely by physicians. Care for sick household members was mostly provided by women. Some slaves possessed medical skills, such as knowledge of herbal remedies and midwifery and often treated both slaves and non-slaves. Covey suggests that because slaveholders offered poor treatment, slaves relied on African remedies and adapted them to North American plants. Other examples of improvised health care methods included folk healers, grandmother midwives, and social networks such as churches, and, for pregnant slaves, female networks. Slave-owners would sometimes also seek healing from such methods in times of ill health.

Researchers performed medical experiments on slaves, who could not refuse, if their owners permitted it. They frequently displayed slaves to illustrate medical conditions. Southern medical schools advertised the ready supply of corpses of the enslaved, for dissection in anatomy classes, as an incentive to enroll.

Separation of families

In the introduction to the oral history project, Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation, the editors wrote:

As masters applied their stamp to the domestic life of the slave quarter, slaves struggled to maintain the integrity of their families. Slaveholders had no legal obligation to respect the sanctity of the slave's marriage bed, and slave women— married or single – had no formal protection against their owners' sexual advances. ...Without legal protection and subject to the master's whim, the slave family was always at risk.

Elizabeth Keckley, who grew up enslaved in Virginia and later became Mary Todd Lincoln's personal modiste, gave an account of how she had witnessed Little Joe, the son of the cook, being sold to pay his enslaver's bad debt:

Joe’s mother was ordered to dress him in his best Sunday clothes and send him to the house, where he was sold, like the hogs, at so much per pound. When her son started for Petersburgh, ... she pleaded piteously that her boy not be taken from her; but master quieted her by telling that he was going to town with the wagon, and would be back in the morning. Morning came, but little Joe did not return to his mother. Morning after morning passed, and the mother went down to the grave without ever seeing her child again. One day she was whipped for grieving for her lost boy.... Burwell never liked to see his slaves wear a sorrowful face, and those who offended in this way were always punished. Alas! the sunny face of the slave is not always an indication of sunshine in the heart.

Between 1790 and 1860, about one million enslaved people were forcefully moved from the states on the Atlantic seabord to the interior in a Second Middle Passage. This normally involved the separation of children from their parents and of husbands from their wives.

Rape and sexual abuse

Owners of enslaved people could legally use them as sexual objects. Therefore, slavery in the United States encompassed wide-ranging rape and sexual abuse, including many forced pregnancies, in order to produce children for sale. Many slaves fought back against sexual attacks, and some died resisting them; others were left with psychological and physical scars. Historian Nell Irvin Painter describes the effects of this abuse as "soul murder".

Rape laws in the South embodied a race-based double standard. Black men accused of rape during the colonial period were often punished with castration, and the penalty was increased to death during the Antebellum Period; however, white men could legally rape their female slaves. Men and boys were also sexually abused by slaveholders. Thomas Foster says that although historians have begun to cover sexual abuse during slavery, few focus on sexual abuse of men and boys because of the assumption that only enslaved women were victimized. Foster suggests that men and boys may have also been forced into unwanted sexual activity; one problem in documenting such abuse is that they, of course, did not bear mixed-race children. Both masters and mistresses were thought to have abused male slaves.

The mistreatment of slaves frequently included rape and the sexual abuse of women. The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in historical Southern culture and its view of the enslaved as property. Although Southern mores regarded white women as dependent and submissive, black women were often consigned to a life of sexual exploitation. Racial purity was the driving force behind the Southern culture's prohibition of sexual relations between white women and black men; however, the same culture protected sexual relations between white men and black women. The result was a number of mixed-race offspring. Many women were raped, and had little control over their families. Children, free women, indentured servants, and men were not immune from abuse by masters and owners(See Children of the plantation.) Children, especially young girls, were often subjected to sexual abuse by their masters, their masters' children, and relatives. Similarly, indentured servants and slave women were often abused. Since these women had no control over where they went or what they did, their masters could manipulate them into situations of high risk, i.e. forcing them into a dark field or making them sleep in their master's bedroom to be available for service. Free or white women could charge their perpetrators with rape, but slave women had no legal recourse; their bodies legally belonged to their owners.

After 1662, when Virginia adopted the legal doctrine partus sequitur ventrem, sexual relations between white men and black women were regulated by classifying children of slave mothers as slaves regardless of their father's race or status. Particularly in the Upper South, a population developed of mixed-race offspring of such unions (see children of the plantation), although white Southern society claimed to abhor miscegenation and punished sexual relations between white women and black men as damaging to racial purity.

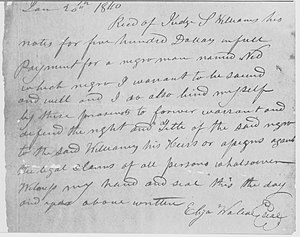

Slave breeding

Slave breeding was the attempt by a slave-owner to influence the reproduction of his slaves for profit. It included forced sexual relations between male and female slaves, encouraging slave pregnancies, sexual relations between master and slave to produce slave children and favoring female slaves who had many children.

For instance, Frederick Douglass (who grew up as a slave in Maryland) reported the systematic separation of slave families and widespread rape of slave women to boost slave numbers. With the development of cotton plantations in the Deep South, planters in the Upper South frequently broke up families to sell "surplus" male slaves to other markets. In addition, court cases such as those of Margaret Garner in Ohio or Celia, a slave in 19th-century Missouri, dealt with women slaves who had been sexually abused by their masters.

Concubines and sexual slaves

The evidence of white men raping slave women was obvious in the many mixed-race children who were born into slavery and part of many households. In some areas, such mixed-race families became the core of domestic and household servants, as at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Both his father-in-law and he took mixed-race enslaved women as concubines after being widowed; each man had six children by those enslaved women. Jefferson's young concubine, Sally Hemings, was 3/4 white, the daughter of his father-in-law John Wayles, making her the half-sister of his late wife.

Many female slaves (known as "fancy maids") were sold at auction into concubinage or prostitution, which was called the "fancy trade". Concubine slaves were the only female slaves who commanded a higher price than skilled male slaves.

Mixed-race children

By the turn of the 19th century many mixed-race families in Virginia dated to Colonial times; white women (generally indentured servants) had unions with slave and free African-descended men. Because of the mother's status, those children were born free and often married other free people of color.

Given the generations of interaction, an increasing number of slaves in the United States during the 19th century were of mixed race. With each generation, the number of mixed-race slaves increased. The 1850, census identified 245,000 slaves as mixed-race (called "mulatto" at the time); by 1860, there were 411,000 slaves classified as mixed-race out of a total slave population of 3,900,000.

Notable examples of mostly-white children born into slavery were the children of Sally Hemings, who it has been speculated are the children of Thomas Jefferson. Since 2000 historians have widely accepted Jefferson's paternity, the change in scholarship has been reflected in exhibits at Monticello and in recent books about Jefferson and his era. Some historians, however, continue to disagree with this conclusion.

Speculation exists on the reasons George Washington freed his slaves in his will. One theory posits that the slaves included two half-sisters of his wife, Martha Custis. Those mixed-race slaves were born to slave women owned by Martha's father, and were regarded within the family as having been sired by him. Washington became the owner of Martha Custis's slaves under Virginia law when he married her and faced the ethical conundrum of owning his wife's sisters.

Planters with mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their education (occasionally in northern schools) or apprenticeship in skilled trades and crafts. Others settled property on them, or otherwise passed on social capital by freeing the children and their mothers. While fewer in number than in the Upper South, free blacks in the Deep South were often mixed-race children of wealthy planters and sometimes benefited from transfers of property and social capital. Wilberforce University, founded by Methodist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) representatives in Ohio in 1856, for the education of African-American youth, was during its early history largely supported by wealthy southern planters who paid for the education of their mixed-race children. When the American Civil War broke out, the majority of the school's 200 students were of mixed race and from such wealthy Southern families. The college closed for several years before the AME Church bought and operated it.

Summaries by survivors of slavery

Historian Ty Seidule uses a quote from Frederick Douglass's autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom to describe the experience of the average male slave as being "robbed of wife, of children, of his hard earnings, of home, of friends, of society, of knowledge, and of all that makes his life desirable."

A quote from a letter by Isabella Gibbons, who had been enslaved by professors at the University of Virginia, is now engraved on the university's Memorial to Enslaved Laborers:

Can we forget the crack of the whip, the cowhide, whipping-post, the auction-block, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten that by those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race have been killed? No, we have not, nor ever will.