Emission trading (ETS) for carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHG) is a form of carbon pricing; also known as cap and trade (CAT) or carbon pricing. It is an approach to limit climate change by creating a market with limited allowances for emissions. This can lower competitiveness of fossil fuels and accelerate investments into low carbon sources of energy such as wind power and photovoltaics. Fossil fuels are the main driver for climate change. They account for 89% of all CO2 emissions and 68% of all GHG emissions.

Emissions trading works by setting a quantitative total limit on the emissions produced by all participating emitters. As a result, the price automatically adjusts to this target. This is the main advantage compared to a fixed carbon tax. Under emission trading, a polluter having more emissions than their quota has to purchase the right to emit more. The entity having fewer emissions sells the right to emit carbon to other entities. As a result, the most cost-effective carbon reduction methods would be exploited first. ETS and carbon taxes are a common method for countries in their attempts to meet their pledges under the Paris Agreement.

Carbon ETS are in operation in China, the European Union and other countries. However, they are usually not harmonized with any defined carbon budgets, which are required to maintain global warming below the critical thresholds of 1.5 °C or "well below" 2 °C. The existing schemes only cover a limited scope of emissions. The EU-ETS focuses on industry and large power generation, leaving the introduction of additional schemes for transport and private consumption to the member states. Though units are counted in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, other potent GHGs such as methane (CH4) or nitrous oxide (N2O) from agriculture are usually not part these schemes yet. Apart from that, an oversupply leads to low prices of allowances with almost no effect on fossil fuel combustion. In September 2021, emission trade allowances (ETAs) covered a wide price range from €7/tCO2 in China's new national carbon market to €63/tCO2 in the EU-ETS. Latest models of the social cost of carbon calculate a damage of more than $3000 per ton CO2 as a result of economy feedbacks and falling global GDP growth rates, while policy recommendations range from about $50 to $200.

History

The international community began the long process towards building effective international and domestic measures to tackle GHG emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydroflurocarbons, perfluorocarbons, sulphur hexafluoride) in response to the increasing assertions that global warming is happening due to man-made emissions and the uncertainty over its likely consequences. That process began in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, when 160 countries agreed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The necessary detail was left to be settled by the UN Conference of Parties (COP).

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was the first major agreement to reduce greenhouse gases. 38 developed countries (Annex 1 countries) committed themselves to targets and timetables.

The resulting inflexible limitations on GHG growth could entail substantial costs if countries have to solely rely on their own domestic measures.

Economics

The economic problem with climate change is that the emitters of greenhouse gases (GHGs) do not face the full cost implications of their actions. These other costs are called external costs. External costs may affect the welfare of others. In the case of climate change, GHG emissions affect the welfare of people now and in the future, as well as affecting the natural environment. The social cost of carbon depends on the future development of emissions. This can be addressed with the dynamic price model of emissions trading.

Distribution of allowances

Emission allowances may be given away for free or auctioned. In the first case, the government receives no carbon revenue and in the second it receives (on average) the full value of the permits. In either case, permits will be equally scarce and just as valuable to market participants. Since the private market (for trading permits) determines the final price of permits (at the time they must be used to cover emissions), the price will be the same in either case (free or auctioned). This is generally understood.

A second point about free permits (usually “grandfathered,” i.e. given out in proportion to past emissions) has often been misunderstood. Companies that receive free permits, treat them as if they had paid full price for them. This is because using carbon in production has the same cost under both arrangements. With auctioned permits, the cost is obvious. With free permits, the cost is the cost of not selling the permit at full value — this is termed an “opportunity cost.” Since the cost of emissions is generally a marginal cost (increasing with output), the cost is passed on by raising the cost of output (e.g. raising the cost of gasoline or electricity).

Windfall profits

A company that receives permits for free will pass on its opportunity cost in the form of higher product prices. Hence, if it sells the same amount of output as before that cap, with no change in production technology, the full value (at the market price) of permits received for free becomes windfall profits. However, since the cap reduces output and often causes the company to incur costs to increase efficiency, windfall profits will be less than the full value of its free permits.

Generally speaking, if permits are allocated to emitters for free, they will profit from them. But if they must pay full price, or if carbon is taxed, their profits will be reduced. If the carbon price exactly equals the true social cost of carbon, then long-run profit reduction will simply reflect the consequences of paying this new cost. If having to pay this cost is unexpected, then there will likely be a one-time loss that is due to the change in regulations and not simply due to paying the real cost of carbon. However, if there is advanced notice of this change, or if the carbon price is introduced gradually, this one-time regulatory cost will be minimized. There has now been enough advance notice of carbon pricing that this effect should be negligible on average.

Carbon emission trading systems and markets

For emissions trading where greenhouse gases are regulated, one emissions permit is considered equivalent to one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Other emissions permits are carbon credits, Kyoto units, assigned amount units, and Certified Emission Reduction units (CER). These permits can be sold privately or in the international market at the prevailing market price. These trade and settle internationally, and hence allow permits to be transferred between countries. Each international transfer is validated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Each transfer of ownership within the European Union is additionally validated by the European Commission.

Emissions trading programmes such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) complement the country-to-country trading stipulated in the Kyoto Protocol by allowing private trading of permits. Under such programmes – which are generally co-ordinated with the national emissions targets provided within the framework of the Kyoto Protocol – a national or international authority allocates permits to individual companies based on established criteria, with a view to meeting national and/or regional Kyoto targets at the lowest overall economic cost.

Other greenhouse gases can also be traded, but are quoted as standard multiples of carbon dioxide with respect to their global warming potential. These features reduce the quota's financial impact on business, while ensuring that the quotas are met at a national and international level.

Exchanges trading in UNFCCC related carbon credits include the European Climate Exchange, NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe, PowerNext, Commodity Exchange Bratislava and the European Energy Exchange. The Chicago Climate Exchange participated until 2010. NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe listed a contract to trade offsets generated by a CDM carbon project called Certified Emission Reductions. Many companies now engage in emissions abatement, offsetting, and sequestration programs to generate credits that can be sold on one of the exchanges. At least one private electronic market has been established in 2008: CantorCO2e. Carbon credits at Commodity Exchange Bratislava are traded at special platform called Carbon place. Various proposals for linking international systems across markets are being investigated. This is being coordinated by the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP).

China

The Chinese national carbon trading scheme is the largest in the world. It is an intensity-based trading system for carbon dioxide emissions by China, which started operating in 2021. The initial design of the system targets a scope of 3.5 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions that come from 1700 installations. It has made a voluntary pledge under the UNFCCC to lower CO2 per unit of GDP by 40 to 45% in 2020 when comparing to the 2005 levels.

In November 2011, China approved pilot tests of carbon trading in seven provinces and cities – Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin as well as Guangdong Province and Hubei Province, with different prices in each region. The pilot is intended to test the waters and provide valuable lessons for the design of a national system in the near future. Their successes or failures will, therefore, have far-reaching implications for carbon market development in China in terms of trust in a national carbon trading market. Some of the pilot regions can start trading as early as 2013/2014. National trading is expected to start in 2017, latest in 2020.

The effort to start a national trading system has faced some problems that took longer than expected to solve, mainly in the complicated process of initial data collection to determine the base level of pollution emission. According to the initial design, there will be eight sectors that are first included in the trading system: chemicals, petrochemicals, iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, building materials, paper, power and aviation, but many of the companies involved lacked consistent data. Therefore, by the end of 2017, the allocation of emission quotas have started but it has been limited to only the power sector and will gradually expand, although the operation of the market is yet to begin. In this system, Companies that are involved will be asked to meet target level of reduction and the level will contract gradually.

European Union

The European Union Emission Trading Scheme (or EU-ETS) is the largest multi-national, greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme in the world. After voluntary trials in the UK and Denmark, Phase I began operation in January 2005 with all 15 member states of the European Union participating. The program caps the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted from large installations with a net heat supply in excess of 20 MW, such as power plants and carbon intensive factories, and covers almost half (46%) of the EU's Carbon Dioxide emissions. Phase I permits participants to trade among themselves and in validated credits from the developing world through Kyoto's Clean Development Mechanism. Credits are gained by investing in clean technologies and low-carbon solutions, and by certain types of emission-saving projects around the world to cover a proportion of their emissions.

During Phases I and II, allowances for emissions have typically been given free to firms, which has resulted in them getting windfall profits. Ellerman and Buchner (2008) suggested that during its first two years in operation, the EU-ETS turned an expected increase in emissions of 1%–2% per year into a small absolute decline. Grubb et al. (2009) suggested that a reasonable estimate for the emissions cut achieved during its first two years of operation was 50–100 MtCO2 per year, or 2.5%–5%.

A number of design flaws have limited the effectiveness of the scheme. In the initial 2005–07 period, emission caps were not tight enough to drive a significant reduction in emissions. The total allocation of allowances turned out to exceed actual emissions. This drove the carbon price down to zero in 2007. This oversupply was caused because the allocation of allowances by the EU was based on emissions data from the European Environmental Agency in Copenhagen, which uses a horizontal activity-based emissions definition similar to the United Nations, the EU-ETS Transaction log in Brussels, but a vertical installation-based emissions measurement system. This caused an oversupply of 200 million tonnes (10% of market) in the EU-ETS in the first phase and collapsing prices.

Phase II saw some tightening, but the use of JI and CDM offsets was allowed, with the result that no reductions in the EU will be required to meet the Phase II cap. For Phase II, the cap is expected to result in an emissions reduction in 2010 of about 2.4% compared to expected emissions without the cap (business-as-usual emissions). For Phase III (2013–20), the European Commission proposed a number of changes, including:

- Setting an overall EU cap, with allowances then allocated;

- Tighter limits on the use of offsets;

- Unlimited banking of allowances between Phases II and III;

- A move from allowances to auction.

In January 2008, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein joined the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS), according to a publication from the European Commission. The Norwegian Ministry of the Environment has also released its draft National Allocation Plan which provides a carbon cap-and-trade of 15 million tonnes of CO2, 8 million of which are set to be auctioned. According to the OECD Economic Survey of Norway 2010, the nation "has announced a target for 2008–12 10% below its commitment under the Kyoto Protocol and a 30% cut compared with 1990 by 2020." In 2012, EU-15 emissions was 15.1% below their base year level. Based on figures for 2012 by the European Environment Agency, EU-15 emissions averaged 11.8% below base-year levels during the 2008–2012 period. This means the EU-15 over-achieved its first Kyoto target by a wide margin.

A 2020 study found that the European Union Emissions Trading System successfully reduced CO2 emissions even though the prices for carbon were set at low prices.

India

Trading is set to begin in 2014 after a three-year rollout period. It is a mandatory energy efficiency trading scheme covering eight sectors responsible for 54 per cent of India's industrial energy consumption. India has pledged a 20 to 25 per cent reduction in emission intensity from 2005 levels by 2020. Under the scheme, annual efficiency targets will be allocated to firms. Tradable energy-saving permits will be issued depending on the amount of energy saved during a target year.

USA

As of 2017, there is no national emissions trading scheme in the United States. Failing to get Congressional approval for such a scheme, President Barack Obama instead acted through the United States Environmental Protection Agency to attempt to adopt through rulemaking the Clean Power Plan, which does not feature emissions trading. The plan was subsequently challenged by the administration of President Donald Trump.

Concerned at the lack of federal action, several states on the east and west coasts have created sub-national cap-and-trade programs.

President Barack Obama in his proposed 2010 United States federal budget wanted to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US$15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would have been auctioned off, generating an estimated $78.7 billion in additional revenue in FY 2012, steadily increasing to $83 billion by FY 2019. The proposal was never made law.

The American Clean Energy and Security Act (H.R. 2454), a greenhouse gas cap-and-trade bill, was passed on 26 June 2009, in the House of Representatives by a vote of 219–212. The bill originated in the House Energy and Commerce Committee and was introduced by Representatives Henry A. Waxman and Edward J. Markey. The political advocacy organizations FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, funded by brothers David and Charles Koch of Koch Industries, encouraged the Tea Party movement to focus on defeating the legislation. Although cap and trade also gained a significant foothold in the Senate via the efforts of Republican Lindsey Graham, Independent and former Democrat Joe Lieberman, and Democrat John Kerry, the legislation died in the Senate.

State and regional programs

In 2003, New York State proposed and attained commitments from nine Northeast states to form a cap-and-trade carbon dioxide emissions program for power generators, called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). This program launched on January 1, 2009, with the aim to reduce the carbon "budget" of each state's electricity generation sector to 10% below their 2009 allowances by 2018.

Also in 2003, U.S. corporations were able to trade CO2 emission allowances on the Chicago Climate Exchange under a voluntary scheme. In August 2007, the Exchange announced a mechanism to create emission offsets for projects within the United States that cleanly destroy ozone-depleting substances.

In 2006, the California Legislature passed the California Global Warming Solutions Act, AB-32. Thus far, flexible mechanisms in the form of project based offsets have been suggested for three main project types. The project types include: manure management, forestry, and destruction of ozone-depleted substances. However, a ruling from Judge Ernest H. Goldsmith of San Francisco's Superior Court stated that the rules governing California's cap-and-trade system were adopted without a proper analysis of alternative methods to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The tentative ruling, issued on January 24, 2011, argued that the California Air Resources Board violated state environmental law by failing to consider such alternatives. If the decision is made final, the state would not be allowed to implement its proposed cap-and-trade system until the California Air Resources Board fully complies with the California Environmental Quality Act. However, on June 24, 2011, the Superior Court's ruling was overturned by the Court of Appeals. By 2012, some of the emitters obtained allowances for free, which is for the electric utilities, industrial facilities and natural gas distributors, whereas some of the others have to go to the auction. The California cap-and-trade program came into effect in 2013.

In 2014, the Texas legislature approved a 10% reduction for the Highly Reactive Volatile Organic Compound (HRVOC) emission limit. This was followed by a 5% reduction for each subsequent year until a total of 25% percent reduction was achieved in 2017.

In February 2007, five U.S. states and four Canadian provinces joined to create the Western Climate Initiative (WCI), a regional greenhouse gas emissions trading system. In July 2010, a meeting took place to further outline the cap-and-trade system. In November 2011, Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah and Washington withdrew from the WCI. As of 2021, only the U.S. state of California and the Canadian province of Quebec participate in the WCI.

In 1997, the State of Illinois adopted a trading program for volatile organic compounds in most of the Chicago area, called the Emissions Reduction Market System. Beginning in 2000, over 100 major sources of pollution in eight Illinois counties began trading pollution credits.

Australia

In 2003 the New South Wales (NSW) state government unilaterally established the New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme to reduce emissions by requiring electricity generators and large consumers to purchase NSW Greenhouse Abatement Certificates (NGACs). This has prompted the rollout of free energy-efficient compact fluorescent lightbulbs and other energy-efficiency measures, funded by the credits. This scheme has been criticised by the Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM) of the UNSW because of its lack of effectiveness in reducing emissions, its lack of transparency and its lack of verification of the additionality of emission reductions.

Both the incumbent Howard Coalition government and the Rudd Labor opposition promised to implement an emissions trading scheme (ETS) before the 2007 federal election. Labor won the election, with the new government proceeding to implement an ETS. The government introduced the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, which the Liberals supported with Malcolm Turnbull as leader. Tony Abbott questioned an ETS, saying the best way to reduce emissions is with a "simple tax". Shortly before the carbon vote, Abbott defeated Turnbull in a leadership challenge, and from there on the Liberals opposed the ETS. This left the government unable to secure passage of the bill and it was subsequently withdrawn.

Julia Gillard defeated Rudd in a leadership challenge and promised not to introduce a carbon tax, but would look to legislate a price on carbon when taking the government to the 2010 election. In the first hung parliament result in 70 years, the government required the support of crossbenchers including the Greens. One requirement for Greens support was a carbon price, which Gillard proceeded with in forming a minority government. A fixed carbon price would proceed to a floating-price ETS within a few years under the plan. The fixed price lent itself to characterisation as a carbon tax and when the government proposed the Clean Energy Bill in February 2011, the opposition claimed it to be a broken election promise.

The bill was passed by the Lower House in October 2011 and the Upper House in November 2011. The Liberal Party vowed to overturn the bill if elected. The bill thus resulted in passage of the Clean Energy Act, which possessed a great deal of flexibility in its design and uncertainty over its future.

The Liberal/National coalition government elected in September 2013 has promised to reverse the climate legislation of the previous government. In July 2014, the carbon tax was repealed as well as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that was to start in 2015.

Canada

The Canadian provinces of Quebec and Nova Scotia operate an emissions trading scheme. Quebec links its program with the US state of California through the Western Climate Initiative.

Japan

The Japanese city of Tokyo is like a country in its own right in terms of its energy consumption and GDP. Tokyo consumes as much energy as "entire countries in Northern Europe, and its production matches the GNP of the world's 16th largest country". A scheme to limit carbon emissions launched in April 2010 covers the top 1,400 emitters in Tokyo, and is enforced and overseen by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Phase 1, which is similar to Japan's scheme, ran until 2015. (Japan had an ineffective voluntary emissions reductions system for years, but no nationwide cap-and-trade program.) Emitters must cut their emissions by 6% or 8% depending on the type of organization; from 2011, those who exceed their limits must buy matching allowances or invest in renewable-energy certificates or offset credits issued by smaller businesses or branch offices. Polluters that fail to comply will be fined up to 500,000 yen plus credits for 1.3 times excess emissions. In its fourth year, emissions were reduced by 23% compared to base-year emissions. In phase 2, (FY2015-FY2019), the target is expected to increase to 15%–17%. The aim is to cut Tokyo's carbon emissions by 25% from 2000 levels by 2020. These emission limits can be met by using technologies such as solar panels and advanced fuel-saving devices.

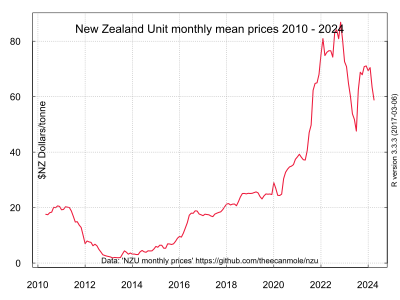

New Zealand

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) is a partial-coverage all-free allocation uncapped highly internationally linked emissions trading scheme. The NZ ETS was first legislated in the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act 2008 in September 2008 under the Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand and then amended in November 2009 and in November 2012 by the Fifth National Government of New Zealand.

The NZ ETS covers forestry (a net sink), energy (43.4% of total 2010 emissions), industry (6.7% of total 2010 emissions) and waste (2.8% of total 2010 emissions) but not pastoral agriculture (47% of 2010 total emissions). Participants in the NZ ETS must surrender two emissions units (either an international 'Kyoto' unit or a New Zealand-issued unit) for every three tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions reported or they may choose to buy NZ units from the government at a fixed price of NZ$25.

Individual sectors of the economy have different entry dates when their obligations to report emissions and surrender emission units take effect. Forestry, which contributed net removals of 17.5 Mts of CO2e in 2010 (19% of NZ's 2008 emissions,) entered the NZ ETS on 1 January 2008. The stationary energy, industrial processes and liquid fossil fuel sectors entered the NZ ETS on 1 July 2010. The waste sector (landfill operators) entered on 1 January 2013. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from pastoral agriculture are not included in the NZ ETS. (From November 2009, agriculture was to enter the NZ ETS on 1 January 2015)

The NZ ETS is highly linked to international carbon markets as it allows the importing of most of the Kyoto Protocol emission units. However, as of June 2015, the scheme will effectively transition into a domestic scheme, with restricted access to international Kyoto units (CERs, ERUs and RMUs). The NZ ETS has a domestic unit; the 'New Zealand Unit' (NZU), which is issued by free allocation to emitters, with no auctions intended in the short term. Free allocation of NZUs varies between sectors. The commercial fishery sector (who are not participants) have a free allocation of units on a historic basis. Owners of pre-1990 forests have received a fixed free allocation of units. Free allocation to emissions-intensive industry, is provided on an output-intensity basis. For this sector, there is no set limit on the number of units that may be allocated. The number of units allocated to eligible emitters is based on the average emissions per unit of output within a defined 'activity'. Bertram and Terry (2010, p 16) state that as the NZ ETS does not 'cap' emissions, the NZ ETS is not a cap and trade scheme as understood in the economics literature.

Some stakeholders have criticized the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme for its generous free allocations of emission units and the lack of a carbon price signal (the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment), and for being ineffective in reducing emissions (Greenpeace Aotearoa New Zealand).

The NZ ETS was reviewed in late 2011 by an independent panel, which reported to the Government and public in September 2011.

South Korea

South Korea's national emissions trading scheme officially launched on 1 January 2015, covering 525 entities from 23 sectors. With a three-year cap of 1.8687 billion tCO2e, it now forms the second largest carbon market in the world following the EU ETS. This amounts to roughly two-thirds of the country's emissions. The Korean emissions trading scheme is part of the Republic of Korea's efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% compared to the business-as-usual scenario by 2020.

United Kingdom

Business in the UK have come out strongly in support of emissions trading as a key tool to mitigate climate change, supported by NGOs. However, not all businesses favor a trading approach. On December 11, 2008, Rex Tillerson, the CEO of ExxonMobil, said a carbon tax is "a more direct, more transparent and more effective approach" than a cap-and-trade program, which he said, "inevitably introduces unnecessary cost and complexity". He also said that he hoped that the revenues from a carbon tax would be used to lower other taxes so as to be revenue neutral.

Market trend

Carbon emissions trading increased rapidly in 2021 with the start of the Chinese national carbon trading scheme. The increasing costs of permits on the EU ETS have had the effect of increasing costs of coal power.

A 2019 study by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE) finds that efforts to put a price on greenhouse gas emissions are growing in North America. "In addition to carbon taxes in effect in Alberta, British Columbia and Boulder, Colorado, cap and trade programs are in effect in California, Quebec, Nova Scotia and the nine northeastern states that form the Regional Greenhouse gas Initiative (RGGI). Several other states and provinces are currently considering putting a price on emissions."

Business reaction

23 multinational corporations came together in the G8 Climate Change Roundtable, a business group formed at the January 2005 World Economic Forum. The group included Ford, Toyota, British Airways, BP and Unilever. On June 9, 2005, the Group published a statement stating the need to act on climate change and stressing the importance of market-based solutions. It called on governments to establish "clear, transparent, and consistent price signals" through "creation of a long-term policy framework" that would include all major producers of greenhouse gases. By December 2007, this had grown to encompass 150 global businesses.

The International Air Transport Association, whose 230 member airlines comprise 93% of all international traffic, position is that trading should be based on "benchmarking", setting emissions levels based on industry averages, rather than "grandfathering", which would use individual companies' previous emissions levels to set their future permit allowances. They argue grandfathering "would penalise airlines that took early action to modernise their fleets, while a benchmarking approach, if designed properly, would reward more efficient operations".

In 2021 shipowners said they are against being included in the EU ETS.

Voluntary surrender of units

There are examples of individuals and organisations purchasing tradable emission permits and 'retiring' (cancelling) them so they cannot be used by emitters to authorise their emissions. This makes the emissions 'cap' lower and therefore further reduces emissions. It is argued that this removes the credits from the carbon market so they cannot be used to allow the emission of carbon and that this reduces the 'cap' on emissions by reducing the number of credits available to emitters.

Criticisms

Critics of carbon trading, such as Carbon Trade Watch, argue that it places disproportionate emphasis on individual lifestyles and carbon footprints, distracting attention from the wider, systemic changes and collective political action that needs to be taken to tackle climate change. Groups such as the Corner House have argued that the market will choose the easiest means to save a given quantity of carbon in the short term, which may be different from the pathway required to obtain sustained and sizable reductions over a longer period, and so a market-led approach is likely to reinforce technological lock-in. For instance, small cuts may often be achieved cheaply through investment in making a technology more efficient, where larger cuts would require scrapping the technology and using a different one. They also argue that emissions trading is undermining alternative approaches to pollution control with which it does not combine well, and so the overall effect it is having is to actually stall significant change to less polluting technologies. In September 2010, campaigning group FERN released "Trading Carbon: How it works and why it is controversial" which compiles many of the arguments against carbon trading.

The Financial Times published an article about cap-and-trade systems which argued that "Carbon markets create a muddle" and "...leave much room for unverifiable manipulation". Lohmann (2009) pointed out that emissions trading schemes create new uncertainties and risks, which can be commodified by means of derivatives, thereby creating a new speculative market.

In China some companies started artificial production of greenhouse gases with sole purpose of their recycling and gaining carbon credits. Similar practices happened in India. Earned credit were then sold to companies in US and Europe.

Proposals for alternative schemes to avoid the problems of cap-and-trade schemes include Cap and Share, which was considered by the Irish Parliament in 2008, and the Sky Trust schemes. These schemes stated that cap-and-trade schemes inherently impact the poor and those in rural areas, who have less choice in energy consumption options.

Carbon trading has been criticised as a form of colonialism, in which rich countries maintain their levels of consumption while getting credit for carbon savings in inefficient industrial projects. Nations that have fewer financial resources may find that they cannot afford the permits necessary for developing an industrial infrastructure, thus inhibiting these countries economic development.

The Kyoto Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism has been criticised for not promoting enough sustainable development.

Another criticism is the claimed possibility of non-existent emission reductions being recorded under the Kyoto Protocol due to the surplus of allowances that some countries possess. For example, Russia had a surplus of allowances due to its economic collapse following the end of the Soviet Union. Other countries could have bought these allowances from Russia, but this would not have reduced emissions. Rather, it would have been simply be a redistribution of emissions allowances. In practice, Kyoto Parties have as yet chosen not to buy these surplus allowances.

Flexibility, and thus complexity, inherent in cap and trade schemes has resulted in a great deal of policy uncertainty surrounding these schemes. Such uncertainty has beset such schemes in Australia, Canada, China, the EU, India, Japan, New Zealand, and the US. As a result of this uncertainty, organizations have little incentive to innovate and comply, resulting in an ongoing battle of stakeholder contestation for the past two decades.

Lohmann (2006b) supported conventional regulation, green taxes, and energy policies that are "justice-based" and "community-driven." According to Carbon Trade Watch (2009), carbon trading has had a "disastrous track record." The effectiveness of the EU ETS was criticized, and it was argued that the CDM had routinely favoured "environmentally ineffective and socially unjust projects."

Annie Leonard's 2009 documentary The Story of Cap and Trade criticized carbon emissions trading for the free permits to major polluters giving them unjust advantages, cheating in connection with carbon offsets, and as a distraction from the search for other solutions.

Offsets

Forest campaigner Jutta Kill (2006) of European environmental group FERN argued that offsets for emission reductions were not substitute for actual cuts in emissions. Kill stated that "[carbon] in trees is temporary: Trees can easily release carbon into the atmosphere through fire, disease, climatic changes, natural decay and timber harvesting."

Permit supply level

Regulatory agencies run the risk of issuing too many emission credits, which can result in a very low price on emission permits. This reduces the incentive that permit-liable firms have to cut back their emissions. On the other hand, issuing too few permits can result in an excessively high permit price. This is an argument for a hybrid instrument having a price-floor, i.e., a minimum permit price, and a price-ceiling, i.e., a limit on the permit price. However, a price-ceiling (safety value) removes the certainty of a particular quantity limit of emissions.

Permit allocation versus auctioning

If polluters receive emission permits for free ("grandfathering"), this may be a reason for them not to cut their emissions because if they do they will receive fewer permits in the future.

This perverse incentive can be alleviated if permits are auctioned, i.e., sold to polluters, rather than giving them the permits for free. Auctioning is a method for distributing emission allowances in a cap-and-trade system whereby allowances are sold to the highest bidder. Revenues from auctioning go to the government and can be used for development of sustainable technology or to cut distortionary taxes, thus improving the efficiency of the overall cap policy.

On the other hand, allocating permits can be used as a measure to protect domestic firms who are internationally exposed to competition. This happens when domestic firms compete against other firms that are not subject to the same regulation. This argument in favor of allocation of permits has been used in the EU ETS, where industries that have been judged to be internationally exposed, e.g., cement and steel production, have been given permits for free).

Structuring issues

Corporate and governmental carbon emission trading schemes have been modified in ways that have been attributed to permitting money laundering to take place. The principal point here is that financial system innovations (outside banking) open up the possibility for unregulated (non-banking) transactions to take place in relativity unsupervised markets.

Public opinion

In the United States, most polling shows large support for emissions trading (often referred to as cap-and-trade). This majority support can be seen in polls conducted by The Washington Post/ABC News, Zogby International and Yale University. A new Washington Post-ABC poll reveals that majorities of the American people believe in climate change, are concerned about it, are willing to change their lifestyles and pay more to address it, and want the federal government to regulate greenhouse gases. They are, however, ambivalent on cap-and-trade.

More than three-quarters of respondents, 77.0%, reported they "strongly support" (51.0%) or "somewhat support" (26.0%) the EPA's decision to regulate carbon emissions. While 68.6% of respondents reported being "very willing" (23.0%) or "somewhat willing" (45.6%), another 26.8% reported being "somewhat unwilling" (8.8%) or "not at all willing" (18.0%) to pay higher prices for "Green" energy sources to support funding for programs that reduce the effect of global warming.

According to PolitiFact, it is a misconception that emissions trading is unpopular in the United States because of earlier polls from Zogby International and Rasmussen which misleadingly include "new taxes" in the questions (taxes aren't part of emissions trading) or high energy cost estimates.