Figure of the heavenly bodies — An illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), depicting Earth as the centre of the Universe.

The center of the Universe is a concept that lacks a coherent definition in modern astronomy; according to standard cosmological theories on the shape of the universe, it has no center.

Historically, different people have suggested various locations

as the center of the Universe. Many mythological cosmologies included an

axis mundi,

the central axis of a flat Earth that connects the Earth, heavens, and

other realms together. In the 4th century BCE Greece, philosophers

developed the geocentric model,

based on astronomical observation; this model proposed that the center

of the Universe lies at the center of a spherical, stationary Earth,

around which the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars rotate. With the

development of the heliocentric model by Nicolaus Copernicus

in the 16th century, the Sun was believed to be the center of the

Universe, with the planets (including Earth) and stars orbiting it.

In the early-20th century, the discovery of other galaxies and the development of the Big Bang theory led to the development of cosmological models of a homogeneous, isotropic Universe, which lacks a central point and is expanding at all points.

Outside astronomy

In religion or mythology, the axis mundi

(also cosmic axis, world axis, world pillar, columna cerului, center of

the world) is a point described as the center of the world, the

connection between it and Heaven, or both.

Mount Hermon in Lebanon was regarded in some cultures as the axis mundi.

Mount Hermon was regarded as the axis mundi in Canaanite tradition, from where the sons of God are introduced descending in 1 Enoch (1En6:6). The ancient Greeks regarded several sites as places of earth's omphalos (navel) stone, notably the oracle at Delphi, while still maintaining a belief in a cosmic world tree and in Mount Olympus as the abode of the gods. Judaism has the Temple Mount and Mount Sinai, Christianity has the Mount of Olives and Calvary, Islam has Mecca, said to be the place on earth that was created first, and the Temple Mount (Dome of the Rock). In Shinto, the Ise Shrine is the omphalos. In addition to the Kun Lun Mountains, where it is believed the peach tree of immortality is located, the Chinese folk religion recognizes four other specific mountains as pillars of the world.

A 1581 map depicting Jerusalem as the center of the world.

Sacred places constitute world centers (omphalos) with the altar

or place of prayer as the axis. Altars, incense sticks, candles and

torches form the axis by sending a column of smoke, and prayer, toward

heaven. The architecture of sacred places often reflects this role.

"Every temple or palace--and by extension, every sacred city or royal

residence--is a Sacred Mountain, thus becoming a Centre." The stupa of Hinduism, and later Buddhism, reflects Mount Meru. Cathedrals are laid out in the form of a cross,

with the vertical bar representing the union of Earth and heaven as the

horizontal bars represent union of people to one another, with the

altar at the intersection. Pagoda structures in Asian temples take the form of a stairway linking Earth and heaven. A steeple in a church or a minaret in a mosque also serve as connections of Earth and heaven. Structures such as the maypole, derived from the Saxons' Irminsul, and the totem pole among indigenous peoples of the Americas also represent world axes. The calumet, or sacred pipe, represents a column of smoke (the soul) rising form a world center. A mandala

creates a world center within the boundaries of its two-dimensional

space analogous to that created in three-dimensional space by a shrine.

In medieval times some Christians thought of Jerusalem as the center of the world (Latin: umbilicus mundi, Greek: Omphalos), and was so represented in the so-called T and O maps. Byzantine hymns speak of the Cross being "planted in the center of the earth."

Center of a flat Earth

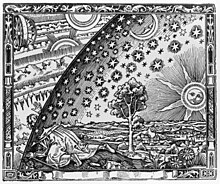

The Flammarion engraving (1888) depicts a traveller who arrives at the edge of a Flat Earth and sticks his head through the firmament.

The Flat Earth model is a belief that the Earth's shape is a plane or disk covered by a firmament containing heavenly bodies. Most pre-scientific cultures have had conceptions of a Flat Earth, including Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Near East until the Hellenistic period, India until the Gupta period (early centuries AD) and China until the 17th century. It was also typically held in the aboriginal cultures of the Americas, and a flat Earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl is common in pre-scientific societies.

"Center" is well-defined in a Flat Earth model. A flat Earth

would have a definite geographic center. There would also be a unique

point at the exact center of a spherical firmament (or a firmament that was a half-sphere).

Earth as the center of the Universe

The Flat Earth model gave way to an understanding of a Spherical Earth. Aristotle

(384–322 BCE) provided observational arguments supporting the idea of a

spherical Earth, namely that different stars are visible in different

locations, travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher

above the horizon, and the shadow of Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round, and spheres cast circular shadows while discs generally do not.

This understanding was accompanied by models of the Universe that depicted the Sun, Moon, stars, and naked eye planets circling the spherical Earth, including the noteworthy models of Aristotle (see Aristotelian physics) and Ptolemy. This geocentric model was the dominant model from the 4th century BCE until the 17th century CE.

Sun as center of the Universe

The heliocentric model from Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a relatively stationary Sun at the center of our Solar System. The word comes from the Greek (ἥλιος helios "sun" and κέντρον kentron "center").

The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BCE by Aristarchus of Samos, but had received no support from most other ancient astronomers.

Nicolaus Copernicus' major theory of a heliocentric model was published in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres),

in 1543, the year of his death, though he had formulated the theory

several decades earlier. Copernicus' ideas were not immediately

accepted, but they did begin a paradigm shift away from the Ptolemaic

geocentric model to a heliocentric model. The Copernican revolution, as this paradigm shift would come to be called, would last until Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Johannes Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe. Kepler's third law was published in 1619. The first law was "The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci."

On 7 January 1610 Galileo used his telescope, with optics superior to what had been available before. He described "three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness", all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it.

Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these

"stars" relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been

inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January Galileo

noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he

attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days he

concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter: Galileo stated that he had reached this conclusion on 11 January. He had discovered three of Jupiter's four largest satellites (moons). He discovered the fourth on 13 January.

His observations of the satellites of Jupiter created a

revolution in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did

not conform to the principles of Aristotelian Cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth.

Many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that

Galileo could have discovered such a thing; by showing that, like

Earth, other planets could also have moons of their own that followed

prescribed paths, and hence that orbital mechanics

didn't apply only to the Earth, planets, and Sun, what Galileo had

essentially done was to show that other planets might be "like Earth".

Newton made clear his heliocentric

view of the Solar System – developed in a somewhat modern way, because

already in the mid-1680s he recognised the "deviation of the Sun" from

the centre of gravity of the solar system.

For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other

body that could be considered at rest, but rather "the common centre of

gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem'd the

Centre of the World", and this centre of gravity "either is at rest or

moves uniformly forward in a right line" (Newton adopted the "at rest"

alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was,

was at rest).

Milky Way's galactic center as center of the Universe

Before the 1920s, it was generally believed that there were no galaxies other than our own (see for example The Great Debate).

Thus, to astronomers of previous centuries, there was no distinction

between a hypothetical center of the galaxy and a hypothetical center of

the universe.

Great Andromeda Nebula by Isaac Roberts (1899)

In 1750 Thomas Wright, in his work An original theory or new hypothesis of the Universe, correctly speculated that the Milky Way might be a body of a huge number of stars held together by gravitational forces rotating about a Galactic Center,

akin to the Solar System but on a much larger scale. The resulting disk

of stars can be seen as a band on the sky from our perspective inside

the disk. In a treatise in 1755, Immanuel Kant elaborated on Wright's idea about the structure of the Milky Way.

The 19th century astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler proposed the Central Sun Hypothesis, according to which the stars of the universe revolved around a point in the Pleiades.

The nonexistence of a center of the Universe

In 1917, Heber Doust Curtis observed a nova within what then was called the "Andromeda

Nebula". Searching the photographic record, 11 more novae were

discovered. Curtis noticed that novas in Andromeda were drastically

fainter than novas in the Milky Way. Based on this, Curtis was able to estimate that Andromeda was 500,000 light-years

away. As a result, Curtis became a proponent of the so-called "island

Universes" hypothesis, which held that objects previously believed to be

spiral nebulae within the Milky Way were actually independent galaxies.

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley

and Curtis took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral

nebulae, and the dimensions of the Universe. To support his claim that

the Great Andromeda Nebula (M31) was an external galaxy, Curtis also

noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in our own

galaxy, as well as the significant Doppler shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik

presented an elegant and simple astrophysical method to estimate the

distance of M31. His result put the Andromeda Nebula far outside our

galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsec, which is about 1,500,000 ly. Edwin Hubble settled the debate about whether other galaxies exist in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of M31. These were made using the 2.5 metre (100 in) Hooker telescope,

and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be

determined. His measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature

was not a cluster of stars and gas within our galaxy, but an entirely

separate galaxy located a significant distance from our own. This proved

the existence of other galaxies.

Expanding Universe

Hubble also demonstrated that the redshift of other galaxies is approximately proportional to their distance from the Earth (Hubble's law).

This raised the appearance of our galaxy being in the center of an

expanding Universe, however, Hubble rejected the findings

philosophically:

...if we see the nebulae all receding from our position in space, then every other observer, no matter where he may be located, will see the nebulae all receding from his position. However, the assumption is adopted. There must be no favoured location in the Universe, no centre, no boundary; all must see the Universe alike. And, in order to ensure this situation, the cosmologist, postulates spatial isotropy and spatial homogeneity, which is his way of stating that the Universe must be pretty much alike everywhere and in all directions."

The redshift observations of Hubble, in which galaxies appear to be

moving away from us at a rate proportional to their distance from us,

are now understood to be a result of the metric expansion of space.

This is the increase of the distance between two distant parts of the

Universe with time, and is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of

space itself changes. As Hubble theorized, all observers anywhere in the

Universe will observe a similar effect.

Copernican and cosmological principles

The Copernican principle, named after Nicolaus Copernicus, states that the Earth is not in a central, specially favored position. Hermann Bondi

named the principle after Copernicus in the mid-20th century, although

the principle itself dates back to the 16th-17th century paradigm shift away from the geocentric Ptolemaic system.

The cosmological principle

is an extension of the Copernican principle which states that the

Universe is homogeneous (the same observational evidence is available to

observers at different locations in the Universe) and isotropic (the

same observational evidence is available by looking in any direction in

the Universe). A homogeneous, isotropic Universe does not have a center.