Scholarly approaches to mysticism include typologies of mysticism and the explanation of mystical states. Since the 19th century, mystical experience has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to "mysticism" but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior, whereas mysticism encompasses a broad range of practices aiming at a transformation of the person, not just inducing mystical experiences.

There is a longstanding discussion on the nature of socalled "introvertive mysticism." Perennialists

regard this kind of mysticism to be universal. A popular variant of

perennialism sees various mystical traditions as pointing to one

universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the

proof. The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars" but "has lost none of its popularity". Instead, a constructionist approach became dominant during the 1970s,

which states that mystical experiences are mediated by pre-existing

frames of reference, while the attribution approach focuses on the

(religious) meaning that is attributed to specific events.

Some neurological research has attempted to identify which areas in the brain are involved in so-called "mystical experience" and the temporal lobe is often claimed to play a significant role, likely attributable to claims made in Vilayanur Ramachandran's 1998 book, Phantoms in the Brain. However, these claims have not stood up to scrutiny.

In mystical and contemplative traditions, mystical experiences are not a goal in themselves, but part of a larger path of self-transformation.

Some neurological research has attempted to identify which areas in the brain are involved in so-called "mystical experience" and the temporal lobe is often claimed to play a significant role, likely attributable to claims made in Vilayanur Ramachandran's 1998 book, Phantoms in the Brain. However, these claims have not stood up to scrutiny.

In mystical and contemplative traditions, mystical experiences are not a goal in themselves, but part of a larger path of self-transformation.

Typologies of mysticism

R. C. Zaehner – natural and religious mysticism

R. C. Zaehner distinguishes three fundamental types of mysticism, namely theistic, monistic and panenhenic ("all-in-one") or natural mysticism. The theistic category includes most forms of Jewish, Christian and Islamic mysticism and occasional Hindu examples such as Ramanuja and the Bhagavad Gita. The monistic type, which according to Zaehner is based upon an experience of the unity of one's soul, includes Buddhism and Hindu schools such as Samhya and Advaita vedanta. Nature mysticism seems to refer to examples that do not fit into one of these two categories.Zaehner considers theistic mysticism to be superior to the other two categories, because of its appreciation of God, but also because of its strong moral imperative. Zaehner is directly opposing the views of Aldous Huxley. Natural mystical experiences are in Zaehner's view of less value because they do not lead as directly to the virtues of charity and compassion. Zaehner is generally critical of what he sees as narcissistic tendencies in nature mysticism.

Zaehner has been criticised by a number of scholars for the "theological violence" which his approach does to non-theistic traditions, "forcing them into a framework which privileges Zaehner's own liberal Catholicism."

Walter T. Stace – extrovertive and introvertive mysticism

Zaehner has also been criticised by Walter Terence Stace in his book Mysticism and philosophy (1960) on similar grounds. Stace argues that doctrinal differences between religious traditions are inappropriate criteria when making cross-cultural comparisons of mystical experiences. Stace argues that mysticism is part of the process of perception, not interpretation, that is to say that the unity of mystical experiences is perceived, and only afterwards interpreted according to the perceiver’s background. This may result in different accounts of the same phenomenon. While an atheist describes the unity as “freed from empirical filling”, a religious person might describe it as “God” or “the Divine”. In “Mysticism and Philosophy”, one of Stace’s key questions is whether there are a set of common characteristics to all mystical experiences.Based on the study of religious texts, which he took as phenomenological descriptions of personal experiences, and excluding occult phenomena, visions, and voices, Stace distinguished two types of mystical experience, namely extrovertive and introvertive mysticism. He describes extrovertive mysticism as an experience of unity within the world, whereas introvertive mysticism is "an experience of unity devoid of perceptual objects; it is literally an experience of 'no-thing-ness'". The unity in extrovertive mysticism is with the totality of objects of perception. While perception stays continuous, “unity shines through the same world”; the unity in introvertive mysticism is with a pure consciousness, devoid of objects of perception, “pure unitary consciousness, wherein awareness of the world and of multiplicity is completely obliterated.” According to Stace such experiences are nonsensical and nonintellectual, under a total “suppression of the whole empirical content.”

| Common Characteristics of Extrovertive Mystical Experiences | Common Characteristics of Introvertive Mystical Experiences |

|---|---|

| 1. The Unifying Vision - all things are One | 1. The Unitary Consciousness; the One, the Void; pure consciousness |

| 2. The more concrete apprehension of the One as an inner subjectivity, or life, in all things | 2. Nonspatial, nontemporal |

| 3. Sense of objectivity or reality | 3. Sense of objectivity or reality |

| 4. Blessedness, peace, etc. | 4. Blessedness, peace, etc. |

| 5. Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine | 5. Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine |

| 6. Paradoxicality | 6. Paradoxicality |

| 7. Alleged by mystics to be ineffable | 7. Alleged by mystics to be ineffable |

Stace finally argues that there is a set of seven common characteristics for each type of mystical experience, with many of them overlapping between the two types. Stace furthermore argues that extrovertive mystical experiences are on a lower level than introvertive mystical experiences.

Stace's categories of "introvertive mysticism" and "extrovertive mysticism" are derived from Rudolf Otto's "mysticism of introspection" and "unifying vision".

William Wainwright distinguishes four different kinds of extrovert mystical experience, and two kinds of introvert mystical experience:

- Extrovert: experiencing the unity of nature; experiencing nature as a living presence; experiencing all nature-phenomena as part of an eternal now; the "unconstructed experience" of Buddhism;

- Introvert: pure empty consciousness; the "mutual love" of theistic experiences.

- Extrovertive experiences: the sense of connectedness (“unity”) of oneself with nature, with a loss of a sense of boundaries within nature; the luminous glow to nature of “nature mysticism”; the presence of God immanent in nature outside of time shining through nature of “cosmic consciousness”; the lack of separate, self-existing entities of mindfulness states;

- Introvertive experiences: theistic experiences of connectedness or identity with God in mutual love; nonpersonal differentiated experiences; the depth-mystical experience empty of all differentiable content.

Although Stace's work on mysticism received a positive response, it has also been strongly criticised in the 1970s and 1980s, for its lack of methodological rigueur and its perennialist pre-assumptions. Major criticisms came from Steven T. Katz in his influential series of publications on mysticism and philosophy, and from Wayne Proudfoot in his Religious experience (1985).

Masson and Masson criticised Stace for using a "buried premise," namely that mysticism can provide valid knowledge of the world, equal to science and logic. A similar criticism has been voiced by Jacob van Belzen toward Hood, noting that Hood validated the existence of a common core in mystical experiences, but based on a test which presupposes the existence of such a common core, noting that "the instrument used to verify Stace's conceptualization of Stace is not independent of Stace, but based on him." Belzen also notes that religion does not stand on its own, but is embedded in a cultural context, which should be taken into account. To this criticism Hood et al. answer that universalistic tendencies in religious research "are rooted first in inductive generalizations from cross-cultural consideration of either faith or mysticism," stating that Stace sought out texts which he recognized as an expression of mystical expression, from which he created his universal core. Hood therefor concludes that Belzen "is incorrect when he claims that items were presupposed."

Mystical experience

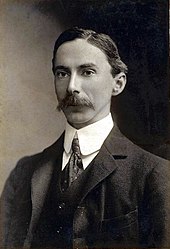

The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience. A "religious experience" is a subjective experience which is interpreted within a religious framework. The concept originated in the 19th century, as a defense against the growing rationalism of western society. Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique. It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential. A broad range of western and eastern movements have incorporated and influenced the emergence of the modern notion of "mystical experience", such as the Perennial philosophy, Transcendentalism, Universalism, the Theosophical Society, New Thought, Neo-Vedanta and Buddhist modernism.William James

William James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his The Varieties of Religious Experience. James wrote:In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness. This is the everlasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime or creed. In Hinduism, in Neoplatonism, in Sufism, in Christian mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think, and which bring it about that the mystical classics have, as been said, neither birthday nor native land.This book is the classic study on religious or mystical experience, which influenced deeply both the academic and popular understanding of "religious experience". James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his Varieties, and influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of the transcendental:

Under the influence of William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience, heavily centered on people's conversion experiences, most philosophers' interest in mysticism has been in distinctive, allegedly knowledge-granting "mystical experiences.James emphasized the personal experience of individuals, and describes a broad variety of such experiences in The Varieties of Religious Experience. He considered the "personal religion" to be "more fundamental than either theology or ecclesiasticism", and defines religion as

...the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine.According to James, mystical experiences have four defining qualities:

- Ineffability. According to James the mystical experience "defies expression, that no adequate report of its content can be given in words".

- Noetic quality. Mystics stress that their experiences give them "insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect." James referred to this as the "noetic" (or intellectual) "quality" of the mystical.

- Transiency. James notes that most mystical experiences have a short occurrence, but their effect persists.

- Passivity. According to James, mystics come to their peak experience not as active seekers, but as passive recipients.

...he shared with thinkers of his era the conviction that beneath the variety could be carved out a certain mystical unanimity, that mystics shared certain common perceptions of the divine, however different their religion or historical epoch...According to Harmless, "for James there was nothing inherently theological in or about mystical experience", and felt it legitimate to separate the mystic's experience from theological claims. Harmless notes that James "denies the most central fact of religion", namely that religion is practiced by people in groups, and often in public. He also ignores ritual, the historicity of religious traditions, and theology, instead emphasizing "feeling" as central to religion.

Inducement of mystical experience

Dan Merkur makes a distinction between trance states and reverie states. According to Merkur, in trance states the normal functions of consciousness are temporarily inhibited, and trance experiences are not filtered by ordinary judgements, and seem to be real and true. In reverie states, numinous experiences are also not inhibited by the normal functions of consciousness, but visions and insights are still perceived as being in need of interpretation, while trance states may lead to a denial of physical reality.Most mystical traditions warn against an attachment to mystical experiences, and offer a "protective and hermeneutic framework" to accommodate these experiences. These same traditions offer the means to induce mystical experiences, which may have several origins:

- Spontaneous; either apparently without any cause, or by persistent existential concerns, or by neurophysiological origins;

- Religious practices, such as contemplation, meditation, and mantra-repetition;

- Entheogens (drugs);

- Neurophysiological origins, such as temporal lobe epilepsy.

Influence

The concept of "mystical experience" has influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of a transcendental reality, cosmic unity, or ultimate truths. Scholars, like Stace and Forman, have tended to exclude visions, near death experiences and parapsychological phenomena from such "special mental states," and focus on sudden experiences of oneness, though neurologically they all seem to be related.Criticism of the concept of "mystical experience"

The notion of "experience", however, has been criticized in religious studies today. Robert Sharf points out that "experience" is a typical Western term, which has found its way into Asian religiosity via western influences. The notion of "experience" introduces a false notion of duality between "experiencer" and "experienced", whereas the essence of kensho is the realisation of the "non-duality" of observer and observed. "Pure experience" does not exist; all experience is mediated by intellectual and cognitive activity. The specific teachings and practices of a specific tradition may even determine what "experience" someone has, which means that this "experience" is not the proof of the teaching, but a result of the teaching. A pure consciousness without concepts, reached by "cleaning the doors of perception", would be an overwhelming chaos of sensory input without coherence.Constructivists such as Steven Katz reject any typology of experiences since each mystical experience is deemed unique.

Other critics point out that the stress on "experience" is accompanied with favoring the atomic individual, instead of the shared life of the community. It also fails to distinguish between episodic experience, and mysticism as a process, that is embedded in a total religious matrix of liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals and practices.

Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:

The privatisation of mysticism – that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences – serves to exclude it from political issues as social justice. Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.

Perennialism, constructionism and contextualism

Scholarly research on mystical experiences in the 19th and 20th century was dominated by a discourse on "mystical experience," laying sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior. Perennialists regard those various experiences traditions as pointing to one universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the prove. In this approach, mystical experiences are privatised, separated from the context in which they emerge. William James, in his The Varieties of Religious Experience, was highly influential in further popularising this perennial approach and the notion of personal experience as a validation of religious truths.The essentialist model argues that mystical experience is independent of the sociocultural, historical and religious context in which it occurs, and regards all mystical experience in its essence to be the same. According to this "common core-thesis", different descriptions can mask quite similar if not identical experiences:

[P]eople can differentiate experience from interpretation, such that different interpretations may be applied to otherwise identical experiences".Principal representants of the perennialist position were William James, Walter Terence Stace, who distinguishes extroverted and introverted mysticism, in response to R. C. Zaehner's distinction between theistic and monistic mysticism; Huston Smith; and Ralph W. Hood, who conducted empirical research using the "Mysticism Scale", which is based on Stace's model.

Since the 1960s, social constructionism argued that mystical experiences are "a family of similar experiences that includes many different kinds, as represented by the many kinds of religious and secular mystical reports". The constructionist states that mystical experiences are fully constructed by the ideas, symbols and practices that mystics are familiair with. shaped by the concepts "which the mystic brings to, and which shape, his experience". What is being experienced is being determined by the expectations and the conceptual background of the mystic. Critics of the "common-core thesis" argue that

[N]o unmediated experience is possible, and that in the extreme, language is not simply used to interpret experience but in fact constitutes experience.The principal representant of the constructionist position is Steven T. Katz, who, in a series of publications, has made a highly influential and compelling case for the constructionist approach.

The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars", but "has lost none of its popularity". The contextual approach has become the common approach, and takes into account the historical and cultural context of mystical experiences.

Steven Katz – constructionism

After Walter Stace's seminal book in 1960, the general philosophy of mysticism received little attention. But in the 1970s the issue of a universal "perennialism" versus each mystical experience being was reignited by Steven Katz. In an often-cited quote he states:There are NO pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences. Neither mystical experience nor more ordinary forms of experience give any indication, or any ground for believing, that they are unmediated [...] The notion of unmediated experience seems, if not self-contradictory, at best empty. This epistemological fact seems to me to be true, because of the sort of beings we are, even with regard to the experiences of those ultimate objects of concern with which mystics have had intercourse, e.g., God, Being, Nirvana, etc.According to Katz (1978), Stace typology is "too reductive and inflexible," reducing the complexities and varieties of mystical experience into "improper categories." According to Katz, Stace does not notice the difference between experience and interpretation, but fails to notice the epistemological issues involved in recognizing such experiences as "mystical," and the even more fundamental issue of which conceptual framework precedes and shapes these experiences. Katz further notes that Stace supposes that similarities in descriptive language also implies a similarity in experience, an assumption which Katz rejects. According to Katz, close examination of the descriptions and their contexts reveals that those experiences are not identical. Katz further notes that Stace held one specific mystical tradition to be superior and normative, whereas Katz rejects reductionist notions and leaves God as God, and Nirvana as Nirvana.

According to Paden, Katz rejects the discrimination between experiences and their interpretations. Katz argues that it is not the description, but the experience itself which is conditioned by the cultural and religious background of the mystic. According to Katz, it is not possible to have pure or unmediated experience.

Yet, according to Laibelman, Katz did not say that the experience can't be unmediated; he said that the conceptual understanding of the experience can't be unmediated, and is based on culturally mediated preconceptions. According to Laibelman, misunderstanding Katz's argument has led some to defend the authenticity of "pure consciousness events," while this is not the issue. Laibelman further notes that a mystic's interpretation is not necessarily more true or correct than the interpretation of an uninvolved observer.

Robert Forman – pure consciousness event

Robert Forman has criticised Katz' approach, arguing that lay-people who describe mystical experiences often notice that this experience involves a totally new form of awareness, which can't be described in their existing frame of reference. Newberg argued that there is neurological evidence for the existence of a "pure consciousness event" empty of any constructionist structuring.Richard Jones – constructivism, anticonstructivism, and perennialism

Richard H. Jones believes that the dispute between "constructionism" and "perennialism" is ill-formed. He draws a distinction between "anticonstructivism" and "perennialism": constructivism can rejected with respect to a certain class of mystical experiences without ascribing to a perennialist philosophy on the relation of mystical doctrines. Constructivism versus anticonstructivism is a matter of the nature of mystical experiences themselves while perennialism is a matter of mystical traditions and the doctrines they espouse. One can reject constructivism about the nature of mystical experiences without claiming that all mystical experiences reveal a cross-cultural "perennial truth". Anticonstructivists can advocate contextualism as much as constructivists do, while perennialists reject the need to study mystical experiences in the context of a mystic's culture since all mystics state the same universal truth.Contextualism and attribution theory

The theoretical study of mystical experience has shifted from an experiential, privatised and perennialist approach to a contextual and empirical approach. The contextual approach, which also includes constructionism and attribution theory, takes into account the historical and cultural context. Neurological research takes an empirical approach, relating mystical experiences to neurological processes.Wayne Proudfoot proposes an approach that also negates any alleged cognitive content of mystical experiences: mystics unconsciously merely attribute a doctrinal content to ordinary experiences. That is, mystics project cognitive content onto otherwise ordinary experiences having a strong emotional impact. Objections have been raised concerning Proudfoot’s use of the psychological data. This approach, however, has been further elaborated by Ann Taves. She incorporates both neurological and cultural approaches in the study of mystical experience.

Many religious and mystical traditions see religious experiences (particularly that knowledge that comes with them) as revelations caused by divine agency rather than ordinary natural processes. They are considered real encounters with God or gods, or real contact with higher-order realities of which humans are not ordinarily aware.

Neurological research

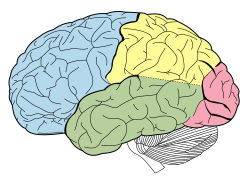

| Lobes of the human brain |

| Lobes of the human brain (temporal lobe is shown in green) |

|---|

The scientific study of mysticism today focuses on two topics: identifying the neurological bases and triggers of mystical experiences, and demonstrating the purported benefits of meditation. Correlates between mystical experiences and neurological activity have been established, pointing to the temporal lobe as the main locus for these experiences, while Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili have also pointed to the parietal lobe.

Temporal lobe

The temporal lobe generates the feeling of "I", and gives a feeling of familiarity or strangeness to the perceptions of the senses. It seems to be involved in mystical experiences, and in the change in personality that may result from such experiences. There is a long-standing notion that epilepsy and religion are linked, and some religious figures may have had temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Raymond Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness (1901) contains several case-studies of persons who have realized "cosmic consciousness"; several of these cases are also being mentioned in J.E. Bryant's 1953 book, Genius and Epilepsy, which has a list of more than 20 people that combines the great and the mystical. James Leuba's The psychology of religious mysticism noted that "among the dread diseases that afflict humanity there is only one that interests us quite particularly; that disease is epilepsy."Slater and Beard renewed the interest in TLE and religious experience in the 1960s. Dewhurst and Beard (1970) described six cases of TLE-patients who underwent sudden religious conversions. They placed these cases in the context of several western saints with a sudden conversion, who were or may have been epileptic. Dewhurst and Beard described several aspects of conversion experiences, and did not favor one specific mechanism.

Norman Geschwind described behavioral changes related to temporal lobe epilepsy in the 1970s and 1980s. Geschwind described cases which included extreme religiosity, now called Geschwind syndrome, and aspects of the syndrome have been identified in some religious figures, in particular extreme religiosity and hypergraphia (excessive writing). Geschwind introduced this "interictal personality disorder" to neurology, describing a cluster of specific personality characteristics which he found characteristic of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Critics note that these characteristics can be the result of any illness, and are not sufficiently descriptive for patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Neuropsychiatrist Peter Fenwick, in the 1980s and 1990s, also found a relationship between the right temporal lobe and mystical experience, but also found that pathology or brain damage is only one of many possible causal mechanisms for these experiences. He questioned the earlier accounts of religious figures with temporal lobe epilepsy, noticing that "very few true examples of the ecstatic aura and the temporal lobe seizure had been reported in the world scientific literature prior to 1980". According to Fenwick, "It is likely that the earlier accounts of temporal lobe epilepsy and temporal lobe pathology and the relation to mystic and religious states owes more to the enthusiasm of their authors than to a true scientific understanding of the nature of temporal lobe functioning."

The occurrence of intense religious feelings in epileptic patients in general is rare, with an incident rate of ca. 2-3%. Sudden religious conversion, together with visions, has been documented in only a small number of individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy. The occurrence of religious experiences in TLE-patients may as well be explained by religious attribution, due to the background of these patients. Nevertheless, the Neuroscience of religion is a growing field of research, searching for specific neurological explanations of mystical experiences. Those rare epileptic patients with ecstatic seizures may provide clues for the neurological mechanisms involved in mystical experiences, such as the anterior insular cortex, which is involved in self-awareness and subjective certainty.

Anterior insula

The insula of the right side, exposed byremoving the opercula

A common quality in mystical experiences is ineffability, a strong feeling of certainty which cannot be expressed in words. This ineffability has been threatened with scepticism. According to Arthur Schopenhauer the inner experience of mysticism is philosophically unconvincing. In The Emotion Machine, Marvin Minsky argues that mystical experiences only seem profound and persuasive because the mind's critical faculties are relatively inactive during them.

Gscwind and Picard propose a neurological explanation for this subjective certainty, based on clinical research of epilepsy. According to Picard, this feeling of certainty may be caused by a dysfunction of the anterior insula, a part of the brain which is involved in interoception, self-reflection, and in avoiding uncertainty about the internal representations of the world by "anticipation of resolution of uncertainty or risk". This avoidance of uncertainty functions through the comparison between predicted states and actual states, that is, "signaling that we do not understand, i.e., that there is ambiguity." Picard notes that "the concept of insight is very close to that of certainty," and refers to Archimedes "Eureka!" Picard hypothesizes that in ecstatic seizures the comparison between predicted states and actual states no longer functions, and that mismatches between predicted state and actual state are no longer processed, blocking "negative emotions and negative arousal arising from predictive unceertainty," which will be experienced as emotional confidence. Picard concludes that "[t]his could lead to a spiritual interpretation in some individuals."

Parietal lobe

Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili, in their book Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, take a perennial stance, describing their insights into the relationship between religious experience and brain function. d'Aquili describes his own meditative experiences as "allowing a deeper, simpler part of him to emerge", which he believes to be "the truest part of who he is, the part that never changes." Not content with personal and subjective descriptions like these, Newberg and d'Aquili have studied the brain-correlates to such experiences. They scanned the brain blood flow patterns during such moments of mystical transcendence, using SPECT-scans, to detect which brain areas show heightened activity. Their scans showed unusual activity in the top rear section of the brain, the "posterior superior parietal lobe", or the "orientation association area (OAA)" in their own words. This area creates a consistent cognition of the physical limits of the self. This OAA shows a sharply reduced activity during meditative states, reflecting a block in the incoming flow of sensory information, resulting in a perceived lack of physical boundaries. According to Newberg and d'Aquili,This is exactly how Robert and generations of Eastern mystics before him have described their peak meditative, spiritual and mystical moments.Newberg and d'Aquili conclude that mystical experience correlates to observable neurological events, which are not outside the range of normal brain function. They also believe that

...our research has left us no choice but to conclude that the mystics may be on to something, that the mind’s machinery of transcendence may in fact be a window through which we can glimpse the ultimate realness of something that is truly divine.Why God Won't Go Away "received very little attention from professional scholars of religion". According to Bulkeley, "Newberg and D'Aquili seem blissfully unaware of the past half century of critical scholarship questioning universalistic claims about human nature and experience". Matthew Day also notes that the discovery of a neurological substrate of a "religious experience" is an isolated finding which "doesn't even come close to a robust theory of religion".