Illustration of the structure of Hell according to Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. By Sandro Botticelli (between 1480 and 1490). According to Carl Gustav Jung, hell represents, among every culture, the disturbing aspect of the collective unconscious.

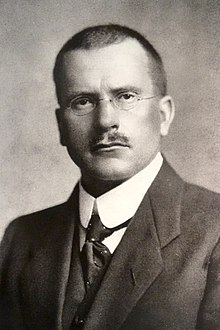

Collective unconscious, a term coined by Carl Jung, refers to structures of the unconscious mind which are shared among beings of the same species. According to Jung, the human collective unconscious is populated by instincts and by archetypes: universal symbols such as The Great Mother, the Wise Old Man, the Shadow, the Tower, Water, the Tree of Life, and many more.

Jung considered the collective unconscious to underpin and surround the unconscious mind, distinguishing it from the personal unconscious of Freudian psychoanalysis.

He argued that the collective unconscious had profound influence on the

lives of individuals, who lived out its symbols and clothed them in

meaning through their experiences. The psychotherapeutic practice of analytical psychology revolves around examining the patient's relationship to the collective unconscious.

Psychiatrist and Jungian analyst Lionel Corbett argues that the

contemporary terms "autonomous psyche" or "objective psyche" are more

commonly used today in the practice of depth psychology rather than the

traditional term of the "collective unconscious."

Critics of the collective unconscious concept have called it

unscientific and fatalistic, or otherwise very difficult to test

scientifically (due to the mythical aspect of the collective

unconscious). Proponents suggest that it is borne out by findings of psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology.

Basic explanation

The term "collective unconscious" first appeared in Jung's 1916 essay, "The Structure of the Unconscious".

This essay distinguishes between the "personal", Freudian unconscious,

filled with sexual fantasies and repressed images, and the "collective"

unconscious encompassing the soul of humanity at large.

In "The Significance of Constitution and Heredity in Psychology" (November 1929), Jung wrote:

And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious.

The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.

On October 19, 1936, Jung delivered a lecture "The Concept of the Collective Unconscious" to the Abernethian Society at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. He said:

My thesis then, is as follows: in addition to our immediate consciousness, which is of a thoroughly personal nature and which we believe to be the only empirical psyche (even if we tack on the personal unconscious as an appendix), there exists a second psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals. This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes, which can only become conscious secondarily and which give definite form to certain psychic contents.

Jung linked the collective unconscious to 'what Freud called "archaic

remnants" – mental forms whose presence cannot be explained by anything

in the individual's own life and which seem to be aboriginal, innate,

and inherited shapes of the human mind'. He credited Freud for developing his "primal horde" theory in Totem and Taboo

and continued further with the idea of an archaic ancestor maintaining

its influence in the minds of present-day humans. Every human being, he

wrote, "however high his conscious development, is still an archaic man

at the deeper levels of his psyche."

As modern humans go through their process of individuation, moving out of the collective unconscious into mature selves, they establish a persona—which can be understood simply as that small portion of the collective psyche which they embody, perform, and identify with.

The collective unconscious exerts overwhelming influence on the

minds of individuals. These effects of course vary widely, since they

involve virtually every emotion and situation. At times, the collective

unconscious can terrify, but it can also heal.

Jung contrasted the collective unconscious with the personal unconscious, the unique aspects of an individual study which Jung says constitute the focus of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler.

Psychotherapy patients, it seemed to Jung, often described fantasies

and dreams which repeated elements from ancient mythology. These

elements appeared even in patients who were probably not exposed to the

original story. For example, mythology offers many examples of the "dual

mother" narrative, according to which a child has a biological mother

and a divine mother. Therefore, argues Jung, Freudian psychoanalysis

would neglect important sources for unconscious ideas, in the case of a

patient with neurosis around a dual-mother image.

This divergence over the nature of the unconscious has been cited as a key aspect of Jung's famous split from Sigmund Freud and his school of psychoanalysis. Some commentators have rejected Jung's characterization of Freud, observing that in texts such as Totem and Taboo (1913) Freud directly addresses the interface between the unconscious and society at large. Jung himself said that Freud had discovered a collective archetype, the Oedipus complex, but that it "was the first archetype Freud discovered, the first and only one".

Probably none of my empirical concepts has met with so much misunderstanding as the idea of the collective unconscious.Jung, October 19, 1936

Jung also distinguished the collective unconscious and collective consciousness,

between which lay "an almost unbridgeable gulf over which the subject

finds himself suspended". According to Jung, collective consciousness

(meaning something along the lines of consensus reality)

offered only generalizations, simplistic ideas, and the fashionable

ideologies of the age. This tension between collective unconscious and

collective consciousness corresponds roughly to the "everlasting cosmic

tug of war between good and evil" and has worsened in the time of the mass man.

Organized religion, exemplified by the Catholic Church, lies more with the collective consciousness; but, through its all-encompassing dogma it channels and molds the images which inevitably pass from the collective unconscious into the minds of people. (Conversely, religious critics including Martin Buber accused Jung of wrongly placing psychology above transcendental factors in explaining human experience.)

Instincts

Jung's exposition of the collective unconscious builds on the classic issue in psychology and biology regarding nature versus nurture.

If we accept that nature, or heredity, has some influence on the

individual psyche, we must examine the question of how this influence

takes hold in the real world.

On exactly one night in its entire lifetime, the yucca moth

discovers pollen in the opened flowers of the yucca plant, forms some

into a pellet, and then transports this pellet, with one of its eggs, to

the pistil of another yucca plant. This activity cannot be "learned";

it makes more sense to describe the yucca moth as experiencing intuition about how to act. Archetypes and instincts coexist in the collective unconscious as interdependent opposites, Jung would later clarify.

Whereas for most animals intuitive understandings completely intertwine

with instinct, in humans the archetypes have become a separate register

of mental phenomena.

Humans experience five main types of instinct,

wrote Jung: hunger, sexuality, activity, reflection, and creativity.

These instincts, listed in order of increasing abstraction, elicit and

constrain human behavior, but also leave room for freedom in their

implementation and especially in their interplay. Even a simple hungry

feeling can lead to many different responses, including metaphorical sublimation. These instincts could be compared to the "drives" discussed in psychoanalysis and other domains of psychology.

Several readers of Jung have observed that in his treatment of the

collective unconscious, Jung suggests an unusual mixture of primordial,

"lower" forces, and spiritual, "higher" forces.

Archetypes

In

an early definition of the term, Jung writes: "Archetypes are typical

modes of apprehension, and wherever we meet with uniform and regularly

recurring modes of apprehension we are dealing with an archetype, no

matter whether its mythological character is recognized or not." He traces the term back to Philo, Irenaeus, and the Corpus Hermeticum, which associate archetypes with divinity and the creation of the world, and notes the close relationship of Platonic ideas.

These archetypes dwell in a world beyond the chronology of a

human lifespan, developing on an evolutionary timescale. Regarding the animus and anima, the male principle within the woman and the female principle within the man, Jung writes:

They evidently live and function in the deeper layers of the unconscious, especially in that phylogenetic substratum which I have called the collective unconscious. This localization explains a good deal of their strangeness: they bring into our ephemeral consciousness an unknown psychic life belonging to a remote past. It is the mind of our unknown ancestors, their way of thinking and feeling, their way of experiencing life and the world, gods and men. The existence of these archaic strata is presumably the source of man's belief in reincarnations and in memories of "previous experiences". Just as the human body is a museum, so to speak, of its phylogenetic history, so too is the psyche.

Jung also described archetypes as imprints of momentous or frequently recurring situations in the lengthy human past.

A complete list of archetypes cannot be made, nor can differences between archetypes be absolutely delineated.

For example, the Eagle, a common archetype that may have a multiplicity

of interpretations. It could mean the soul leaving the mortal body and

connecting with the heavenly spheres. Or it may mean that someone is

sexually impotent, in that they have had their spiritual ego body

engaged. In spite of this difficulty Jungian analyst June Singer suggests a partial list of well-studied archetypes, listed in pairs of opposites:

| Ego | Shadow |

|---|---|

| Great Mother | Tyrannical Father |

| Old Wise Man | Trickster |

| Anima | Animus |

| Meaning | Absurdity |

| Centrality | Diffusion |

| Order | Chaos |

| Opposition | Conjunction |

| Time | Eternity |

| Sacred | Profane |

| Light | Darkness |

| Transformation | Fixity |

Jung made reference to contents of this category of the unconscious psyche as being similar to Levy-Bruhl's use of collective representations or "représentations collectives," Mythological "motifs," Hubert and Mauss's "categories of the imagination," and Adolf Bastian's "primordial thoughts." He also called archetypes "dominants" because of their profound influence on mental life.

Evidence

In

his clinical psychiatry practice, Jung identified mythological elements

which seemed to recur in the minds of his patients—above and beyond the

usual complexes which could be explained in terms of their personal

lives.

The most obvious patterns applied to the patient's parents: "Nobody

knows better than the psychotherapist that the mythologizing of the

parents is often pursued far into adulthood and is given up only with

the greatest resistance."

Jung cited recurring themes as evidence of the existence of

psychic elements shared among all humans. For example: "The snake-motif

was certainly not an individual acquisition of the dreamer, for

snake-dreams are very common even among city-dwellers who have probably

never seen a real snake." Still better evidence, he felt, came when patients described complex images and narratives with obscure mythological parallels.

Jung's leading example of this phenomenon was a paranoid-schizophrenic

patient who could see the sun's dangling phallus, whose motion caused

wind to blow on earth. Jung found a direct analogue of this idea in the "Mithras Liturgy", from the Greek Magical Papyri

of Ancient Egypt—only just translated into German—which also discussed a

phallic tube, hanging from the sun, and causing wind to blow on earth.

He concluded that the patient's vision and the ancient Liturgy arose

from the same source in the collective unconscious.

Going beyond the individual mind, Jung believed that "the whole

of mythology could be taken as a sort of projection of the collective

unconscious". Therefore, psychologists could learn about the collective

unconscious by studying religions and spiritual practices of all cultures, as well as belief systems like astrology.

Criticism of Jung's evidence

Popperian critic Ray Scott Percival disputes some of Jung's examples and argues that his strongest claims are not falsifiable.

Percival takes especial issue with Jung's claim that major scientific

discoveries emanate from the collective unconscious and not from

unpredictable or innovative work done by scientists. Percival charges

Jung with excessive determinism

and writes: "He could not countenance the possibility that people

sometimes create ideas that cannot be predicted, even in principle."

Regarding the claim that all humans exhibit certain patterns of mind,

Percival argues that these common patterns could be explained by common

environments (i.e. by shared nurture, not nature). Because all people

have families, encounter plants and animals, and experience night and

day, it should come as no surprise that they develop basic mental

structures around these phenomena.

This latter example has been the subject of contentious debate, and Jung critic Richard Noll has argued against its authenticity.

Ethology and biology

Animals all have some innate psychological concepts which guide their mental development. The concept of imprinting in ethology

is one well-studied example, dealing most famously with the Mother

constructs of newborn animals. The many predetermined scripts for animal

behavior are called innate releasing mechanisms.

Proponents of the collective unconscious theory in neuroscience

suggest that mental commonalities in humans originate especially from

the subcortical area of the brain: specifically, the thalamus and limbic system.

These centrally located structures link the brain to the rest of the

nervous system and said to control vital processes including emotions

and long-term memory .

Archetype research

A

more common experimental approach investigates the unique effects of

archetypal images. An influential study of this type, by Rosen, Smith,

Huston, & Gonzalez in 1991, found that people could better remember

symbols paired with words representing their archetypal meaning. Using

data from the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism

and a jury of evaluators, Rosen et al. developed an "Archetypal Symbol

Inventory" listing symbols and one-word connotations. Many of these

connotations were obscure to laypeople. For example, a picture of a

diamond represented "self"; a square represented "Earth". They found

that even when subjects did not consciously associate the word with the

symbol, they were better able to remember the pairing of the symbol

with its chosen word.

Brown & Hannigan replicated this result in 2013, and expanded the

study slightly to include tests in English and in Spanish of people who

spoke both languages.

Maloney (1999) asked people questions about their feelings to

variations on images featuring the same archetype: some positive, some

negative, and some non-anthropomorphic. He found that although the

images did not elicit significantly different responses to questions

about whether they were "interesting" or "pleasant", but did provoke

highly significant differences in response to the statement: "If I were

to keep this image with me forever, I would be". Maloney suggested that

this question led the respondents to process the archetypal images on a

deeper level, which strongly reflected their positive or negative

valence.

Ultimately, although Jung referred to the collective unconscious as an empirical concept, based on evidence, its elusive nature does create a barrier to traditional experimental research. June Singer writes:

But the collective unconscious lies beyond the conceptual limitations of individual human consciousness, and thus cannot possibly be encompassed by them. We cannot, therefore, make controlled experiments to prove the existence of the collective unconscious, for the psyche of man, holistically conceived, cannot be brought under laboratory conditions without doing violence to its nature. [...] In this respect, psychology may be compared to astronomy, the phenomena of which also cannot be enclosed within a controlled setting. The heavenly bodies must be observed where they exist in the natural universe, under their own conditions, rather than under conditions we might propose to set for them.

Exploration

Moře (Sea), Eduard Tomek, 1971

Proof of the existence of a collective unconscious, and insight into its nature, could be gleaned primarily from dreams and from active imagination, a waking exploration of fantasy.

Jung considered that 'the shadow' and the anima and animus

differ from the other archetypes in the fact that their content is more

directly related to the individual's personal situation'.

These archetypes, a special focus of Jung's work, become autonomous

personalities within an individual psyche. Jung encouraged direct

conscious dialogue of the patient's with these personalities within. While the shadow usually personifies the personal unconscious, the anima or the Wise Old Man can act as representatives of the collective unconscious.

Jung suggested that parapsychology, alchemy, and occult religious ideas could contribute understanding of the collective unconscious. Based on his interpretation of synchronicity and extra-sensory perception, Jung argued that psychic activity transcended the brain. In alchemy, Jung found that plain water, or seawater, corresponded to his concept of the collective unconscious.

In humans, the psyche mediates between the primal force of the

collective unconscious and the experience of consciousness or dream.

Therefore, symbols may require interpretation before they can be

understood as archetypes. Jung writes:

We have only to disregard the dependence of dream language on environment and substitute "eagle" for "aeroplane," "dragon" for "automobile" or "train," "snake-bite" for "injection," and so forth, in order to arrive at the more universal and more fundamental language of mythology. This give us access to the primordial images that underlie all thinking and have a considerable influence even on our scientific ideas.

A single archetype can manifest in many different ways. Regarding the

Mother archetype, Jung suggests that not only can it apply to mothers,

grandmothers, stepmothers, mothers-in-law, and mothers in mythology, but

to various concepts, places, objects, and animals:

Other symbols of the mother in a figurative sense appear in things representing the goal of our longing for redemption, such as Paradise, the Kingdom of God, the Heavenly Jerusalem. Many things arousing devotion or feelings of awe, as for instance the Church, university, city or country, heaven, earth, the woods, the sea or any still waters, matter even, the underworld and the moon, can be mother-symbols. The archetype is often associated with things and places standing for fertility and fruitfulness: the cornucopia, a ploughed field, a garden. It can be attached to a rock, a cave, a tree, a spring, a deep well, or to various vessels such as the baptismal font, or to vessel-shaped flowers like the rose or the lotus. Because of the protection it implies, the magic circle or mandala can be a form of mother archetype. Hollow objects such as ovens or cooking vessels are associated with the mother archetype, and, of course, the uterus, yoni, and anything of a like shape. Added to this list there are many animals, such as the cow, hare, and helpful animals in general.

Care must be taken, however, to determine the meaning of a symbol

through further investigation; one cannot simply decode a dream by

assuming these meanings are constant. Archetypal explanations work best

when an already-known mythological narrative can clearly help to explain

the confusing experience of an individual.

Application to psychotherapy

Psychotherapy

based on analytical psychology would seek to analyze the relationship

between a person's individual consciousness and the deeper common

structures which underlie them. Personal experiences both activate

archetypes in the mind and give them meaning and substance for

individual.

At the same time, archetypes covertly organize human experience and

memory, their powerful effects becoming apparent only indirectly and in

retrospect. Understanding the power of the collective unconscious can help an individual to navigate through life.

In the interpretation of analytical psychologist Mary Williams, a

patient who understands the impact of the archetype can help to

dissociate the underlying symbol from the real person who embodies the

symbol for the patient. In this way, the patient no longer uncritically

transfers their feelings about the archetype onto people in everyday

life, and as a result can develop healthier and more personal

relationships.

Practitioners of analytic psychotherapy, Jung cautioned, could

become so fascinated with manifestations of the collective unconscious

that they facilitated their appearance at the expense of their patient's

well-being. Schizophrenics,

it is said, fully identify with the collective unconscious, lacking a

functioning ego to help them deal with actual difficulties of life.

Application to politics and society

Elements

from the collective unconscious can manifest among groups of people,

who by definition all share a connection to these elements. Groups of

people can become especially receptive to specific symbols due to the

historical situation they find themselves in. The common importance of the collective unconscious makes people ripe for political manipulation, especially in the era of mass politics. Jung compared mass movements to mass psychoses, comparable to demonic possession in which people uncritically channel unconscious symbolism through the social dynamic of the mob and the leader.

Although civilization

leads people to disavow their links with the mythological world of

uncivilized societies, Jung argued that aspects of the primitive

unconscious would nevertheless reassert themselves in the form of superstitions, everyday practices, and unquestioned traditions such as the Christmas tree.

Based on empirical inquiry, Jung felt that all humans, regardless

of racial and geographic differences, share the same collective pool of

instincts and images, though these manifest differently due to the

moulding influence of culture.

However, above and in addition to the primordial collective

unconscious, people within a certain culture may share additional bodies

of primal collective ideas.

Jung called the UFO phenomenon a "living myth", a legend in the process of consolidation.

Belief in a messianic encounter with UFOs demonstrated the point, Jung

argued, that even if a rationalistic modern ideology repressed the

images of the collective unconscious, its fundamental aspects would

inevitably resurface. The circular shape of the flying saucer confirms

its symbolic connection to repressed but psychically necessary ideas of

divinity.

The universal applicability of archetypes has not escaped the attention of marketing specialists, who observe that branding can resonate with consumers through appeal to archetypes of the collective unconscious.

Minimal and maximal interpretations

In

a minimalist interpretation of what would then appear as "Jung's much

misunderstood idea of the collective unconscious", his idea was "simply

that certain structures and predispositions of the unconscious are

common to all of us...[on] an inherited, species-specific, genetic

basis".

Thus "one could as easily speak of the 'collective arm' – meaning the

basic pattern of bones and muscles which all human arms share in

common."

Others point out however that "there does seem to be a basic

ambiguity in Jung's various descriptions of the Collective Unconscious.

Sometimes he seems to regard the predisposition to experience certain

images as understandable in terms of some genetic model" – as with the collective arm. However, Jung was "also at pains to stress the numinous

quality of these experiences, and there can be no doubt that he was

attracted to the idea that the archetypes afford evidence of some

communion with some divine or world mind', and perhaps 'his popularity

as a thinker derives precisely from this" – the maximal interpretation.

Marie-Louise von Franz

accepted that "it is naturally very tempting to identify the hypothesis

of the collective unconscious historically and regressively with the

ancient idea of an all-extensive world-soul." New Age

writer Sherry Healy goes further, claiming that Jung himself "dared to

suggest that the human mind could link to ideas and motivations called

the collective unconscious...a body of unconscious energy that lives

forever." This is the idea of monopsychism.