Carl Jung

| |

|---|---|

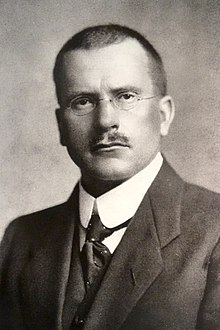

A portrait of Jung, unknown date

| |

| Born |

Carl Gustav Jung

26 July 1875 |

| Died | 6 June 1961 (aged 85) |

| Alma mater | University of Basel |

| Known for | Analytical psychology Psychological types Collective unconscious Complex Archetypes Anima and animus Synchronicity Shadow Extraversion and introversion |

| Spouse(s) | Emma Jung |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry, psychology, psychotherapy, analytical psychology |

| Institutions | Burghölzli, Swiss Army (commissioned officer in World War I) |

| Doctoral advisor | Eugen Bleuler |

| Influences | Arthur Schopenhauer, Eugen Bleuler, Friedrich Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Immanuel Kant, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, Otto Rank, Rudolf Otto, Sigmund Freud |

| Influenced | Joseph Campbell, Hermann Hesse, Erich Neumann, Ross Nichols, Alan Watts, Jordan Peterson, Terence McKenna, Gaston Bachelard |

| Signature | |

| |

Carl Gustav Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology.

Jung's work was influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, and religious studies. Jung worked as a research scientist at the famous Burghölzli hospital, under Eugen Bleuler. During this time, he came to the attention of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The two men conducted a lengthy correspondence and collaborated, for a while, on a joint vision of human psychology.

Freud saw the younger Jung as the heir he had been seeking to take forward his "new science" of psychoanalysis and to this end secured his appointment as President of his newly founded International Psychoanalytical Association. Jung's research and personal vision, however, made it impossible for him to bend to his older colleague's doctrine, and a schism became inevitable. This division was personally painful for Jung, and it was to have historic repercussions lasting well into the modern day.

Among the central concepts of analytical psychology is individuation—the lifelong psychological process of differentiation of the self out of each individual's conscious and unconscious elements. Jung considered it to be the main task of human development. He created some of the best known psychological concepts, including synchronicity, archetypal phenomena, the collective unconscious, the psychological complex, and extraversion and introversion.

Jung was also an artist, craftsman and builder as well as a prolific writer. Many of his works were not published until after his death and some are still awaiting publication.

Biography

Early years

Childhood

The clergy house in Kleinhüningen, Basel where Jung grew up

Carl Gustav Jung was born in Kesswil, in the Swiss canton of Thurgau,

on 26 July 1875 as the second and first surviving son of Paul Achilles

Jung (1842–1896) and Emilie Preiswerk (1848–1923). Their first child,

born in 1873, was a boy named Paul who survived only a few days.

Being the youngest son of a noted Basel physician of German descent,

also called Karl Gustav Jung (1794–1864), whose hopes of achieving a

fortune never materialised, Paul Jung did not progress beyond the status

of an impoverished rural pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church;

his wife had also grown up in a large family, whose Swiss roots went

back five centuries. Emilie was the youngest child of a distinguished Basel churchman and academic, Samuel Preiswerk (1799–1871), and his second wife. Preiswerk was antistes, the title given to the head of the Reformed clergy in the city, as well as a Hebraist, author and editor, who taught Paul Jung as his professor of Hebrew at Basel University.

When Jung was six months old, his father was appointed to a more prosperous parish in Laufen,

but the tension between his parents was growing. Emilie Jung was an

eccentric and depressed woman; she spent considerable time in her

bedroom where she said that spirits visited her at night.

Although she was normal during the day, Jung recalled that at night his

mother became strange and mysterious. He reported that one night he saw

a faintly luminous and indefinite figure coming from her room with a

head detached from the neck and floating in the air in front of the

body. Jung had a better relationship with his father.

Jung's mother left Laufen for several months of hospitalization near Basel

for an unknown physical ailment. His father took the boy to be cared

for by Emilie Jung's unmarried sister in Basel, but he was later brought

back to his father's residence. Emilie Jung's continuing bouts of

absence and depression deeply troubled her son and caused him to

associate women with "innate unreliability", whereas "father" meant for

him reliability but also powerlessness.

In his memoir, Jung would remark that this parental influence was the

"handicap I started off with. Later, these early impressions were

revised: I have trusted men friends and been disappointed by them, and I

have mistrusted women and was not disappointed." After three years of living in Laufen, Paul Jung requested a transfer. In 1879 he was called to Kleinhüningen, next to Basel, where his family lived in a parsonage of the church. The relocation brought Emilie Jung closer into contact with her family and lifted her melancholy.

When he was nine years old, Jung's sister Johanna Gertrud (1884–1935)

was born. Known in the family as "Trudi", she later became a secretary

to her brother.

Memories of childhood

Jung was a solitary and introverted child. From childhood, he believed that, like his mother, he had two personalities—a modern Swiss citizen and a personality more suited to the 18th century.

"Personality Number 1", as he termed it, was a typical schoolboy living

in the era of the time. "Personality Number 2" was a dignified,

authoritative and influential man from the past. Although Jung was close

to both parents, he was disappointed by his father's academic approach

to faith.

A number of childhood memories made lifelong impressions on him. As a boy, he carved a tiny mannequin

into the end of the wooden ruler from his pencil case and placed it

inside the case. He added a stone, which he had painted into upper and

lower halves, and hid the case in the attic. Periodically, he would

return to the mannequin, often bringing tiny sheets of paper with

messages inscribed on them in his own secret language.

He later reflected that this ceremonial act brought him a feeling of

inner peace and security. Years later, he discovered similarities

between his personal experience and the practices associated with totems in indigenous cultures, such as the collection of soul-stones near Arlesheim or the tjurungas

of Australia. He concluded that his intuitive ceremonial act was an

unconscious ritual, which he had practiced in a way that was strikingly

similar to those in distant locations which he, as a young boy, knew

nothing about. His observations about symbols, archetypes, and the collective unconscious were inspired, in part, by these early experiences combined with his later research.

At the age of 12, shortly before the end of his first year at the Humanistisches Gymnasium

in Basel, Jung was pushed to the ground by another boy so hard that he

momentarily lost consciousness. (Jung later recognized that the incident

was indirectly his fault.) A thought then came to him—"now you won't

have to go to school anymore."

From then on, whenever he walked to school or began homework, he

fainted. He remained at home for the next six months until he overheard

his father speaking hurriedly to a visitor about the boy's future

ability to support himself. They suspected he had epilepsy.

Confronted with the reality of his family's poverty, he realized the

need for academic excellence. He went into his father's study and began

poring over Latin grammar.

He fainted three more times but eventually overcame the urge and did

not faint again. This event, Jung later recalled, "was when I learned

what a neurosis is."

University studies and early career

Initially,

Jung had aspirations of becoming a preacher or minister in his early

life. There was a strong moral sense in his household and several of his

family members were clergymen as well. After studying philosophy in his

teens, Jung decided against the path of religious traditionalism and

decided instead to pursue psychiatry and medicine. His interest was immediately captured—it combined the biological and the spiritual, exactly what he was searching for. In 1895 Jung began to study medicine at the University of Basel.

Barely a year later in 1896, his father Paul died and left the family

near destitute. They were helped out by relatives who also contributed

to Jung's studies.

During his student days, he entertained his contemporaries with the

family legend, that his paternal grandfather was the illegitimate son of

Goethe

and his German great-grandmother, Sophie Ziegler. In later life, he

pulled back from this tale, saying only that Sophie was a friend of

Goethe's niece.

In 1900, Jung moved to Zürich and began working at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital under Eugen Bleuler. Bleuler was already in communication with the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud. Jung's dissertation, published in 1903, was titled On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena. In 1905 Jung was appointed as a permanent 'senior' doctor at the hospital and also became a lecturer Privatdozent in the medical faculty of Zurich University. In 1906 he published Diagnostic Association Studies, which Freud obtained a copy of. In 1909, Jung left the psychiatric hospital and began a private practice in his home in Küsnacht.

Eventually a close friendship and a strong professional association developed between the elder Freud and Jung, which left a sizeable correspondence. For six years they cooperated in their work. In 1912, however, Jung published Psychology of the Unconscious,

which made manifest the developing theoretical divergence between the

two. Consequently, their personal and professional relationship

fractured—each stating that the other was unable to admit he could

possibly be wrong. After the culminating break in 1913, Jung went

through a difficult and pivotal psychological transformation,

exacerbated by the outbreak of the First World War. Henri Ellenberger called Jung's intense experience a "creative illness" and compared it favorably to Freud's own period of what he called neurasthenia and hysteria.

Marriage

In 1903, Jung married Emma Rauschenbach,

seven years his junior and the elder daughter of a wealthy

industrialist in eastern Switzerland, Johannes Rauschenbach-Schenck, and

his wife. Rauschenbach was the owner, among other concerns, of IWC Schaffhausen—the

International Watch Company, manufacturers of luxury time-pieces. Upon

his death in 1905, his two daughters and their husbands became owners of

the business. Jung's brother-in-law—Ernst Homberger—became

the principal proprietor, but the Jungs remained shareholders in a

thriving business that ensured the family's financial security for

decades.

Emma Jung, whose education had been limited, evinced considerable

ability and interest in her husband's research and threw herself into

studies and acted as his assistant at Burghölzli. She eventually became a

noted psychoanalyst in her own right. They had five children: Agathe,

Gret, Franz, Marianne, and Helene. The marriage lasted until Emma's

death in 1955.

During his marriage, Jung engaged in extramarital relationships. His alleged affairs with Sabina Spielrein and Toni Wolff

were the most widely discussed. Though it was mostly taken for granted

that Jung's relationship with Spielrein included a sexual relationship,

this assumption has been disputed, in particular by Henry Zvi Lothane.

Wartime army service

During

World War I, Jung was drafted as an army doctor and soon made

commandant of an internment camp for British officers and soldiers. The

Swiss were neutral, and obliged to intern personnel from either side of

the conflict who crossed their frontier to evade capture. Jung worked to

improve the conditions of soldiers stranded in Switzerland and

encouraged them to attend university courses.

Relationship with Freud

Meeting and collaboration

Jung was thirty when he sent his Studies in Word Association to Sigmund Freud in Vienna

in 1906. The two men met for the first time the following year and Jung

recalled the discussion between himself and Freud as interminable. He

recalled that they talked almost unceasingly for thirteen hours. Six months later, the then 50-year-old Freud sent a collection of his latest published essays to Jung in Zurich. This marked the beginning of an intense correspondence and collaboration that lasted six years and ended in May 1913.

At that time Jung resigned as the chairman of the International

Psychoanalytical Association, a position to which he had been elected

with Freud's support.

Group photo 1909 in front of Clark University. Front row, Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung. Back row, Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi.

Jung and Freud influenced each other during the intellectually

formative years of Jung's life. Jung had become interested in psychiatry

as a student by reading Psychopathia Sexualis by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. In 1900, Jung completed his degree, and started work as an intern (voluntary doctor) under the psychiatrist, Eugen Bleuler at Burghölzli Hospital. It was Bleuler who introduced him to the writings of Freud by asking him to write a review of The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). In the early 1900s psychology

as a science was still in its early stages, but Jung became a qualified

proponent of Freud's new "psycho-analysis." At the time, Freud needed

collaborators and pupils to validate and spread his ideas. Burghölzli

was a renowned psychiatric clinic in Zurich and Jung's research had

already gained him international recognition. In 1906 he published Diagnostic Association Studies, and later sent a copy of this book to Freud—who had already bought a copy. Preceded by a lively correspondence, Jung met Freud for the first time, in Vienna on 3 March 1907. In 1908, Jung became an editor of the newly founded Yearbook for Psychoanalytical and Psychopathological Research.

In 1909, Jung travelled with Freud and Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi to the United States; they took part in a conference at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. The conference at Clark University was planned by the psychologist G. Stanley Hall

and included twenty-seven distinguished psychiatrists, neurologists and

psychologists. It represented a watershed in the acceptance of

psychoanalysis in North America. This forged welcome links between Jung

and influential Americans. Jung returned to the United States the next year for a brief visit.

In 1910 Freud proposed Jung, "his adopted eldest son, his crown

prince and successor," for the position of life-time President of the

newly formed International Psychoanalytical Association.

However, after forceful objections from his Viennese colleagues, it was

agreed Jung would be elected to serve a two-year term of office.

Divergence and break

Jung outside Burghölzli in 1910

While Jung worked on his Psychology of the Unconscious: a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido, tensions manifested between him and Freud because of various disagreements, including those concerning the nature of libido. Jung de-emphasized

the importance of sexual development and focused on the collective

unconscious: the part of the unconscious that contains memories and

ideas that Jung believed were inherited from ancestors. While he did

think that libido was an important source for personal growth, unlike

Freud, Jung did not believe that libido alone was responsible for the

formation of the core personality. Jung believed his personal development was influenced by factors he felt were unrelated to sexuality.

In 1912 these tensions came to a peak because Jung felt severely slighted after Freud visited his colleague Ludwig Binswanger in Kreuzlingen

without paying him a visit in nearby Zurich, an incident Jung referred

to as "the Kreuzlingen gesture". Shortly thereafter, Jung again traveled

to the United States and gave the Fordham University lectures, a six-week series, which were published later in the year as Psychology of the Unconscious: a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido, (subsequently republished as Symbols of Transformation).

While they contain some remarks on Jung's dissenting view on the

libido, they represent largely a "psychoanalytical Jung" and not the

theory of analytical psychology, for which he became famous in the

following decades. Nonetheless it was their publication which, Jung

declared, “cost me my friendship with Freud”.

Another primary disagreement with Freud stemmed from their differing concepts of the unconscious.

Jung saw Freud's theory of the unconscious as incomplete and

unnecessarily negative and inelastic. According to Jung, Freud conceived

the unconscious solely as a repository of repressed emotions and

desires. Jung's observations overlap to an extent with Freud's model of the unconscious, what Jung called the "personal unconscious",

but his hypothesis is more about a process than a static model and he

also proposed the existence of a second, overarching form of the

unconscious beyond the personal, that he named the psychoid—a term

borrowed from Driesch, but with a somewhat altered meaning. The collective unconscious is not so much a 'geographical location', but a deduction from the alleged ubiquity of archetypes

over space and time. Freud had actually mentioned a collective level of

psychic functioning but saw it primarily as an appendix to the rest of

the psyche.

In November 1912, Jung and Freud met in Munich for a meeting among prominent colleagues to discuss psychoanalytical journals. At a talk about a new psychoanalytic essay on Amenhotep IV,

Jung expressed his views on how it related to actual conflicts in the

psychoanalytic movement. While Jung spoke, Freud suddenly fainted and

Jung carried him to a couch.

Jung and Freud personally met for the last time in September 1913

for the Fourth International Psychoanalytical Congress in Munich. Jung

gave a talk on psychological types, the introverted and extraverted type in analytical psychology.

This constituted the introduction of some of the key concepts which

came to distinguish Jung's work from Freud's in the next half century.

Midlife isolation

It was the publication of Jung's book Psychology of the Unconscious

in 1912 that led to the break with Freud. Letters they exchanged show

Freud's refusal to consider Jung's ideas. This rejection caused what

Jung described in his (posthumous) 1962 autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections,

as a "resounding censure". Everyone he knew dropped away except for two

of his colleagues. Jung described his book as "an attempt, only

partially successful, to create a wider setting for medical psychology

and to bring the whole of the psychic phenomena within its purview." The

book was later revised and retitled Symbols of Transformation in 1922.

London 1913–14

Jung

spoke at meetings of the Psycho-Medical Society in London in 1913 and

1914. His travels were soon interrupted by the war, but his ideas

continued to receive attention in England primarily through the efforts

of Constance Long who translated and published the first English volume

of his collected writings.

The Red Book

In

1913, at the age of thirty-eight, Jung experienced a horrible

"confrontation with the unconscious". He saw visions and heard voices.

He worried at times that he was "menaced by a psychosis" or was "doing a

schizophrenia". He decided that it was valuable experience and, in

private, he induced hallucinations or, in his words, "active imaginations".

He recorded everything he felt in small journals. Jung began to

transcribe his notes into a large red leather-bound book, on which he

worked intermittently for sixteen years.

Jung left no posthumous instructions about the final disposition of what he called the Liber Novus or the Red Book. Sonu Shamdasani,

a historian of psychology from London, tried for three years to

persuade Jung's resistant heirs to have it published. Up to

mid-September 2008, fewer than two dozen people had seen it. Ulrich

Hoerni, Jung's grandson who manages the Jung archives, decided to

publish it to raise the additional funds needed when the Philemon Foundation was founded.

In 2007, two technicians for DigitalFusion, working with New York City publishers W. W. Norton & Company,

scanned the manuscript with a 10,200-pixel scanner. It was published on

7 October 2009, in German with a "separate English translation along

with Shamdasani's introduction and footnotes" at the back of the book,

according to Sara Corbett for The New York Times. She wrote, "The book is bombastic, baroque and like so much else about Carl Jung, a willful oddity, synched with an antediluvian and mystical reality."

The Rubin Museum of Art in New York City displayed the original Red Book journal, as well as some of Jung's original small journals, from 7 October 2009 to 15 February 2010.

According to them, "During the period in which he worked on this book

Jung developed his principal theories of archetypes, collective

unconscious, and the process of individuation." Two-thirds of the pages

bear Jung's illuminations of the text.

Travels

Jung

emerged from his period of isolation in the late nineteen-teens with the

publication of several journal articles, followed in 1921 with Psychological Types, one of his most influential books. There followed a decade of active publication, interspersed with overseas travels.

England (1920, 1923, 1925, 1938)

Constance Long arranged for Jung to deliver a seminar in Cornwall in 1920. Another seminar was held in 1923, this one organized by Helton Godwin Baynes (known as Peter), and another in 1925.

In 1938, Jung was awarded with an honorary degree from Oxford.

At the tenth International Medical Congress for Psychotherapy held at

Oxford from 29 July to 2 August 1938, Jung gave the presidential

address, followed by a visit to Cheshire to stay with the Bailey family

at Lawton Mere.

United States 1909–12, 1924–25, 1936–37

During the period of Jung's collaboration with Freud, both visited the US in 1909 to lecture at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts

where both were awarded honorary degrees. In 1912 Jung gave a series of

lectures at Fordham University, New York which were published later in

the year as Psychology of the Unconscious.

Jung made a more extensive trip westward in the winter of 1924–5,

financed and organized by Fowler McCormick and George Porter. Of

particular value to Jung was a visit with Chief Mountain Lake of the Taos Pueblo near Taos, New Mexico.

Jung made another trip to America in 1936, giving lectures in New York

and New England for his growing group of American followers. He returned

in 1937 to deliver the Terry Lectures at Yale University, later published as Psychology and Religion.

East Africa

In October 1925, Jung embarked on his most ambitious expedition, the "Bugishu Psychological Expedition" to East Africa. He was accompanied by Peter Baynes and an American associate, George Beckwith.

On the voyage to Africa, they became acquainted with an English woman

named Ruth Bailey, who joined their safari a few weeks later. The group

traveled through Kenya and Uganda to the slopes of Mount Elgon,

where Jung hoped to increase his understanding of "primitive

psychology" through conversations with the culturally isolated residents

of that area. Later he concluded that the major insights he had gleaned

had to do with himself and the European psychology in which he had been

raised.

India

In December

1937, Jung left Zurich again for an extensive tour of India with Fowler

McCormick. In India, he felt himself "under the direct influence of a

foreign culture" for the first time. In Africa, his conversations had

been strictly limited by the language barrier, but in India he was able

to converse extensively. Hindu philosophy became an important element in

his understanding of the role of symbolism and the life of the

unconscious, though he avoided a meeting with Ramana Maharshi.

He described Ramana as being absorbed in "the self", but admitted to

not understanding Ramana's self-realization or what he actually did do.

He also admitted that his field of psychology was not competent to

understand the eastern insight of the Atman "the self". Jung became seriously ill on this trip and endured two weeks of delirium in a Calcutta hospital. After 1938, his travels were confined to Europe.

Later years and death

Jung

became a full professor of medical psychology at the University of

Basel in 1943, but resigned after a heart attack the next year to lead a

more private life. He became ill again in 1952.

C. G. Jung Institute, Küsnacht, Switzerland

Jung continued to publish books until the end of his life, including Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies (1959), which analyzed the archetypal meaning and possible psychological significance of the reported observations of UFOs. He also enjoyed a friendship with an English Roman Catholic priest, Father Victor White, who corresponded with Jung after he had published his controversial Answer to Job.

In 1961, Jung wrote his last work, a contribution to Man and His Symbols entitled "Approaching the Unconscious" (published posthumously in 1964). Jung died on 6 June 1961 at Küsnacht after a short illness. He had been beset by circulatory diseases.

Thought

Jung's

thought was formed by early family influences, which on the maternal

side were a blend of interest in the occult and in solid reformed

academic theology. On his father's side were two important figures, his

grandfather the physician and academic scientist, Karl Gustav Jung and

the family's actual connection with Lotte Kestner, the niece of the

German polymath, Johann Wolfgang Goethe' s "Löttchen".

Although he was a practicing clinician and writer and as such founded analytical psychology, much of his life's work was spent exploring related areas such as physics, vitalism, Eastern and Western philosophy, alchemy, astrology, and sociology, as well as literature

and the arts. Jung's interest in philosophy and the occult led many to

view him as a mystic, although his preference was to be seen as a man of

science.

Key concepts

The major concepts of analytical psychology as developed by Jung include:

Archetype – a concept "borrowed" from anthropology

to denote supposedly universal and recurring mental images or themes.

Jung's definitions of archetypes varied over time and have been the

subject of debate as to their usefulness.

Archetypal images

– universal symbols that can mediate opposites in the psyche, often

found in religious art, mythology and fairy tales across cultures

Complex – the repressed organisation of images and experiences that governs perception and behaviour

Extraversion and introversion – personality traits of degrees of openness or reserve contributing to psychological type.

Shadow – the repressed, therefore unknown, aspects of the personality including those often considered to be negative

Collective unconscious – aspects of unconsciousness experienced by all people in different cultures

Anima – the contrasexual aspect of a man's psyche, his inner personal feminine conceived both as a complex and an archetypal image

Animus – the contrasexual aspect of a woman's psyche, her inner personal masculine conceived both as a complex and an archetypal image

Self

– the central overarching concept governing the individuation process,

as symbolised by mandalas, the union of male and female, totality,

unity. Jung viewed it as the psyche's central archetype

Individuation

– the process of fulfilment of each individual "which negates neither

the conscious or unconscious position but does justice to them both".

Synchronicity – an acausal principle as a basis for the apparently random simultaneous occurrence of phenomena.

Extraversion and introversion

Jung was one of the first people to define introversion and extraversion in a psychological context. In Jung's Psychological Types,

he theorizes that each person falls into one of two categories, the

introvert and the extravert. These two psychological types Jung compares

to ancient archetypes, Apollo and Dionysus.

The introvert is likened with Apollo, who shines light on

understanding. The introvert is focused on the internal world of

reflection, dreaming and vision. Thoughtful and insightful, the

introvert can sometimes be uninterested in joining the activities of

others. The extravert is associated with Dionysus, interested in joining

the activities of the world. The extravert is focused on the outside

world of objects, sensory perception and action. Energetic and lively,

the extravert may lose their sense of self in the intoxication of

Dionysian pursuits. Jungian introversion and extraversion is quite different from the modern idea of introversion and extraversion.

Modern theories often stay true to behaviourist means of describing

such a trait (sociability, talkativeness, assertiveness etc.) whereas

Jungian introversion and extraversion is expressed as a perspective:

introverts interpret the world subjectively, whereas extraverts interpret the world objectively.

Persona

In his psychological theory – which is not necessarily linked to a particular theory of social structure – the persona appears as a consciously created personality or identity, fashioned out of part of the collective psyche through socialization, acculturation and experience. Jung applied the term persona, explicitly because, in Latin, it means both personality and the masks worn by Roman actors of the classical period, expressive of the individual roles played.

The persona, he argues, is a mask for the "collective

psyche", a mask that 'pretends' individuality, so that both self and

others believe in that identity, even if it is really no more than a

well-played role through which the collective psyche is expressed. Jung regarded the "persona-mask" as a complicated system which mediates

between individual consciousness and the social community: it is "a

compromise between the individual and society as to what a man should

appear to be". But he also makes it quite explicit that it is, in substance, a character mask

in the classical sense known to theatre, with its double function: both

intended to make a certain impression on others, and to hide (part of)

the true nature of the individual. The therapist then aims to assist the individuation process through which the client (re)gains their "own self" – by liberating the self, both from the deceptive cover of the persona, and from the power of unconscious impulses.

Jung has become enormously influential in management theory; not

just because managers and executives have to create an appropriate

"management persona" (a corporate mask) and a persuasive identity, but also because they have to evaluate what sort of people the workers are, in order to manage them (for example, using personality tests and peer reviews).

Spirituality

Jung's work on himself and his patients convinced him that life has a spiritual purpose beyond material goals. Our main task, he believed, is to discover and fulfill our deep, innate potential. Based on his study of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Gnosticism, Taoism, and other traditions, Jung believed that this journey of transformation, which he called individuation, is at the mystical heart of all religions. It is a journey to meet the self and at the same time to meet the Divine. Unlike Freud's objectivist worldview, Jung's pantheism

may have led him to believe that spiritual experience was essential to

our well-being, as he specifically identifies individual human life with

the universe as a whole.

Jung's ideas on religion counterbalance Freudian skepticism. Jung's

idea of religion as a practical road to individuation is still treated

in modern textbooks on the psychology of religion, though his ideas have also been criticized.

Jung recommended spirituality as a cure for alcoholism, and he is considered to have had an indirect role in establishing Alcoholics Anonymous. Jung once treated an American patient (Rowland Hazard III), suffering from chronic alcoholism.

After working with the patient for some time and achieving no

significant progress, Jung told the man that his alcoholic condition was

near to hopeless, save only the possibility of a spiritual experience.

Jung noted that, occasionally, such experiences had been known to reform

alcoholics when all other options had failed.

Hazard took Jung's advice seriously and set about seeking a

personal, spiritual experience. He returned home to the United States

and joined a First-Century Christian evangelical movement known as the Oxford Group

(later known as Moral Re-Armament). He also told other alcoholics what

Jung had told him about the importance of a spiritual experience. One of

the alcoholics he brought into the Oxford Group was Ebby Thacher, a long-time friend and drinking buddy of Bill Wilson, later co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous

(AA). Thacher told Wilson about the Oxford Group and, through them,

Wilson became aware of Hazard's experience with Jung. The influence of

Jung thus indirectly found its way into the formation of Alcoholics

Anonymous, the original twelve-step program.

The above claims are documented in the letters of Jung and Bill Wilson, excerpts of which can be found in Pass It On, published by Alcoholics Anonymous.

Although the detail of this story is disputed by some historians, Jung

himself discussed an Oxford Group member, who may have been the same

person, in talks given around 1940. The remarks were distributed

privately in transcript form, from shorthand taken by an attender (Jung

reportedly approved the transcript), and later recorded in Volume 18 of

his Collected Works, The Symbolic Life,

For instance, when a member of the Oxford Group comes to me in order to get treatment, I say, 'You are in the Oxford Group; so long as you are there, you settle your affair with the Oxford Group. I can't do it better than Jesus.

Jung goes on to state that he has seen similar cures among Roman Catholics.

Paranormal beliefs

Jung had an apparent interest in the paranormal and occult. For decades he attended seances

and claimed to have witnessed "parapsychic phenomena". Initially he

attributed these to psychological causes, even delivering 1919 lecture

in England for the Society for Psychical Research on "The Psychological

Foundations for the belief in spirits". However, he began to "doubt whether an exclusively psychological approach can do justice to the phenomena in question" and stated that "the spirit hypothesis yields better results".

Jung's ideas about the paranormal culminated in "synchronicity",

his idea that meaningful connections in the world manifest through

coincidence with no apparent causal link. What he referred to as

“acausal connecting principle”. Despite his own experiments failing to confirm the phenomenon he held on to the idea as an explanation for apparent ESP. As well as proposing it as a functional explanation for how the I-Ching worked, although he was never clear about how synchronicity worked.

Interpretation of quantum mechanics

Jung influenced one philosophical interpretation (not the science) of quantum physics with the concept of synchronicity regarding some events as non-causal. That idea influenced the physicist Wolfgang Pauli (with whom, via a letter correspondence, he developed the notion of unus mundus in connection with the notion of nonlocality) and some other physicists.

Alchemy

The work and writings of Jung from the 1940s onwards focused on alchemy.

In 1944 Jung published Psychology and Alchemy,

in which he analyzed the alchemical symbols and came to the conclusion

that there is a direct relationship between them and the

psychoanalytical process.

He argued that the alchemical process was the transformation of the

impure soul (lead) to perfected soul (gold), and a metaphor for the

individuation process.

In 1963 Mysterium Coniunctionis first appeared in English as part of The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Mysterium Coniunctionis was Jung's last book and focused on the "Mysterium Coniunctionis" archetype, known as the sacred marriage

between sun and moon. Jung argued that the stages of the alchemists,

the blackening, the whitening, the reddening and the yellowing, could be

taken as symbolic of individuation — his favourite term for personal

growth (75).

Art therapy

Jung

proposed that art can be used to alleviate or contain feelings of

trauma, fear, or anxiety and also to repair, restore and heal.

In his work with patients and in his own personal explorations, Jung

wrote that art expression and images found in dreams could be helpful in

recovering from trauma and emotional distress. At times of emotional

distress, he often drew, painted, or made objects and constructions

which he recognized as more than recreational.

Dance/movement therapy

Dance/movement therapy as an active imagination was created by C.G. Jung and Toni Wolff in 1916 and was practiced by Tina Keller-Jenny and other analysts, but remained largely unknown until the 1950s when it was rediscovered by Marian Chace and therapist Mary Whitehouse, who after studying with Martha Graham and Mary Wigman, became herself a dancer and dance teacher of modern dance, as well as Trudy Schoop in 1963, who is considered one of the founders of the dance/movement therapy in the United States.

Political views

Views on the state

Jung stressed the importance of individual rights

in a person's relation to the state and society. He saw that the state

was treated as "a quasi-animate personality from whom everything is

expected" but that this personality was "only camouflage for those

individuals who know how to manipulate it", and referred to the state as a form of slavery. He also thought that the state "swallowed up [people's] religious forces",

and therefore that the state had "taken the place of God"—making it

comparable to a religion in which "state slavery is a form of worship".

Jung observed that "stage acts of [the] state" are comparable to

religious displays: "Brass bands, flags, banners, parades and monster

demonstrations are no different in principle from ecclesiastical

processions, cannonades and fire to scare off demons".

From Jung's perspective, this replacement of God with the state in a

mass society leads to the dislocation of the religious drive and results

in the same fanaticism of the church-states of the Dark Ages—wherein the more the state is 'worshipped', the more freedom and morality are suppressed; this ultimately leaves the individual psychically undeveloped with extreme feelings of marginalization.

Germany, 1933 to 1939

Jung had many friends and respected colleagues who were Jewish and he maintained relations with them through the 1930s when anti-semitism

in Germany and other European nations was on the rise. However, until

1939, he also maintained professional relations with psychotherapists in

Germany who had declared their support for the Nazi regime and there were allegations that he himself was a Nazi sympathizer.

In 1933, after the Nazis gained power in Germany, Jung took part in restructuring of the General Medical Society for Psychotherapy (Allgemeine Ärztliche Gesellschaft für Psychotherapie), a German-based professional body with an international membership. The society was reorganized into two distinct bodies:

- A strictly German body, the Deutsche Allgemeine Ärztliche Gesellschaft für Psychotherapie, led by Matthias Göring, an Adlerian psychotherapist and a cousin of the prominent Nazi Hermann Göring

- International General Medical Society for Psychotherapy, led by Jung. The German body was to be affiliated to the international society, as were new national societies being set up in Switzerland and elsewhere.

The International Society's constitution permitted individual doctors

to join it directly, rather than through one of the national affiliated

societies, a provision to which Jung drew attention in a circular in

1934.

This implied that German Jewish doctors could maintain their

professional status as individual members of the international body,

even though they were excluded from the German affiliate, as well as

from other German medical societies operating under the Nazis.

As leader of the international body, Jung assumed overall responsibility for its publication, the Zentralblatt für Psychotherapie. In 1933, this journal published a statement endorsing Nazi positions and Hitler's book Mein Kampf. In 1934, Jung wrote in a Swiss publication, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, that he experienced "great surprise and disappointment" when the Zentralblatt associated his name with the pro-Nazi statement.

Jung went on to say "the main point is to get a young and insecure science into a place of safety during an earthquake". He did not end his relationship with the Zentralblatt at this time, but he did arrange the appointment of a new managing editor, Carl Alfred Meier of Switzerland. For the next few years, the Zentralblatt

under Jung and Meier maintained a position distinct from that of the

Nazis, in that it continued to acknowledge contributions of Jewish

doctors to psychotherapy. In the face of energetic German attempts to Nazify the international body, Jung resigned from its presidency in 1939, the year the Second World War started.

Anti-Semitism and Nazism

Jung's interest in European mythology and folk psychology has led to accusations of Nazi sympathies, since they shared the same interest. He became, however, aware of the negative impact of these similarities:

Jung clearly identifies himself with the spirit of German Volkstumsbewegung throughout this period and well into the 1920s and 1930s, until the horrors of Nazism finally compelled him to reframe these neopagan metaphors in a negative light in his 1936 essay on Wotan.

There are writings showing that Jung's sympathies were against, rather than for, Nazism.

In his 1936 essay "Wotan", Jung described the influence of Hitler on

Germany as "one man who is obviously 'possessed' has infected a whole

nation to such an extent that everything is set in motion and has

started rolling on its course towards perdition."

Jung would later say that:

Hitler seemed like the 'double' of a real person, as if Hitler the man might be hiding inside like an appendix, and deliberately so concealed in order not to disturb the mechanism ... You know you could never talk to this man; because there is nobody there ... It is not an individual; it is an entire nation.

In an interview with Carol Baumann in 1948, Jung denied rumors regarding any sympathy for the Nazi movement, saying:

It must be clear to anyone who has read any of my books that I have never been a Nazi sympathizer and I never have been anti-Semitic, and no amount of misquotation, mistranslation, or rearrangement of what I have written can alter the record of my true point of view. Nearly every one of these passages has been tampered with, either by malice or by ignorance. Furthermore, my friendly relations with a large group of Jewish colleagues and patients over a period of many years in itself disproves the charge of anti-Semitism.

Others have argued contrary to this, with reference to his writings, correspondence and public utterances of the 1930s. Attention has been drawn to articles Jung published in the Zentralblatt fur Psychotherapie

stating: “The Aryan unconscious has a greater potential than the

Jewish unconscious” and "The Jew, who is something of a nomad, has never

yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never

will". His remarks on the qualities of the "Aryan

unconscious" and the “corrosive character” of Freud's “Jewish gospel”

have been cited as evidence of an anti-semitism “fundamental to the

structure of Jung’s thought”.

However, Aniela Jaffé says that such sentences must be put in the

context of the many positive statements Jung made about Jews and

Judaism,

and that the above quoted claims were framed by his argument that Jews

are a "race with a three-thousand year civilization", while "Aryans"

were race with a "youthfulness not yet weaned from barbarism."

Jung saw the former as "possessing the inestimable advantage of greater

consciousness and differentiation, while the latter were closer to

nature and unlike Jews, capable of creating new cultural forms". For

Jung, the "epithet "barbarism" was anything but a compliment".

During the 1930s, Jung had worked to protect Jewish psychologists

from antisemitic legislation enacted by the Nazis. Jung's individual

efforts to aid persecuted German-Jewish psychologists were known only to

a few; however, during this period he discreetly helped a large number

of Jewish colleagues with active and personal support in their efforts

to escape the Nazi regime - and many of those he helped in this period

would later become friends of his.

Service to the Allies during World War II

Jung was in contact with Allen Dulles of the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency) and provided valuable intelligence on the psychological condition of Hitler.

Dulles referred to Jung as "Agent 488" and offered the following

description of his service: “Nobody will probably ever know how much

Professor Jung contributed to the Allied Cause during the war, by seeing

people who were connected somehow with the other side.” Jung's service

to the Allied cause through the OSS remained classified after the war.

Legacy

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a popular psychometric instrument, and the concepts of socionics

were developed from Jung's theory of psychological types. Jung saw the

human psyche as "by nature religious" and made this religiousness the

focus of his explorations. Jung is one of the best known contemporary

contributors to dream analysis and symbolization. His influence on popular psychology, the "psychologization of religion", spirituality and the New Age movement has been immense. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Jung as the 23rd most cited psychologist of the 20th century.

In popular culture

Literature

- Laurens van der Post, Afrikaner author who claimed to have had a 16-year friendship with Jung, from which a number of books and a film were created about Jung's life. The accuracy of van der Post's claims about the closeness of his relationship to Jung has been questioned.

- Hermann Hesse, author of works such as Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, was treated by Joseph Lang, a student of Jung. For Hesse this began a long preoccupation with psychoanalysis, through which he came to know Jung personally.

- In his novel The World is Made of Glass (1983) Morris West gives a fictional account of one of Jung's cases, placing the events in 1913. As stated in the author's note, the novel is "based upon a case recorded, very briefly, by Carl Gustav Jung in his autobiographical work Memories, Dreams, Reflections".

Art

Original statue of Jung in Mathew Street, Liverpool, a half-body on a plinth captioned "Liverpool is the pool of life"

- The visionary Swiss painter Peter Birkhäuser was treated by a student of Jung, Marie-Louise von Franz, and corresponded with Jung regarding the translation of dream symbolism into works of art.

- American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock underwent Jungian psychotherapy in 1939 with Joseph Henderson. His therapist made the decision to engage him through his art, and had Pollock make drawings, which led to the appearance of many Jungian concepts in his paintings.

- Contrary to some sources, Jung did not visit Liverpool but recorded a dream in which he had, and of which he wrote "Liverpool is the pool of life, it makes to live." As a result, a statue of Jung was erected in Mathew Street in 1987 but, being made of plaster, was vandalised and replaced by a more durable version in 1993.

Music

- Musician David Bowie described himself as Jungian in his relationship to dreams and the unconscious. Bowie sang of Jung on his album Aladdin Sane (a word play on sanity) and attended the exhibition of The Red Book in New York with artist Tony Oursler, who described Bowie as "... reading and speaking of the psychoanalyst with passion". Bowie's 1967 song "Shadow Man" poetically encapsulates a key Jungian concept, while in 1987 Bowie tellingly described the Glass Spiders of Never Let Me Down as Jungian mother figures around which he not only anchored a worldwide tour, but also created an enormous onstage effigy.

- Argentinian musician Luis Alberto Spinetta was influenced by the texts of Carl Jung in the development of his 1975 conceptual album Durazno sangrando, specifically in the songs "Encadenado al ánima" and "En una lejana playa del ánimus", which deal with the jungian concepts of Anima and Animus.

- Jung appeared on the front cover of The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

- BTS's 2019 album Map of the Soul: Persona is based on Jung's Map of the Soul, which gives basic principles of Jung's analytical psychology. The album includes an intro song titled Persona rapped by group leader RM, who asks the question 'who am I?', and is confronted with various versions of himself with words such as "Persona", "Shadow", and "Ego", which refer to Jung's theories.

Theatre, film and television

- Federico Fellini brought to the screen an exuberant imagery shaped by his encounter with the ideas of Jung, especially Jungian dream interpretation. Fellini preferred Jung to Freud because Jungian analysis defined the dream not as a symptom of a disease that required a cure but rather as a link to archetypal images shared by all of humanity.

- BBC interview with Jung for Face to Face with John Freeman at Jung's home in Zurich. 1959.

- Stanley Kubrick's 1987 film Full Metal Jacket features an underlying theme about the duality of man throughout the action and dialogue of the film. One scene plays out this way: A colonel asks a soldier, "You write 'Born to Kill' on your helmet and you wear a peace button. What's that supposed to be, some kind of sick joke?" To which the soldier replies, "I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir... The Jungian thing, sir."

- The Soul Keeper, a 2002 film about Sabina Spielrein and Jung.

- The Talking Cure, a 2002 play by Christopher Hampton

- A Dangerous Method, a 2011 film directed by David Cronenberg based on Hampton's play The Talking Cure, is a fictional dramatisation of Jung's life as a psychoanalyst between 1904 and 1913. It mainly concerns his relationships with Freud and Sabina Spielrein, a Russian woman who became his lover and student and, later, an analyst herself.

- Matter of Heart (1986), a documentary on Jung featuring interviews with those who knew him and archive footage.

- Carl Gustav Jung, Salomón Shang, 2007. A documentary film made of interviews with C. G. Jung, found in American university archives.

- The World Within. C. G. Jung in his own words, 1990 documentary (on YouTube)

Video games

- The Persona series of games is heavily based on his theories, as is the Nights into Dreams series of games. Xenogears for the original PlayStation and its associated works — including its re-imagination as the “Xenosaga” trilogy and a graphic novel published by the game’s creator entitled “Perfect Works” — are centered around Jungian concepts.

Bibliography

Books

- 1912 Psychology of the Unconscious

- 1921 Psychological Types

- 1933 Modern Man in Search of a Soul

- 1938 Psychology and Religion

- 1951 Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self

- 1952 Symbols of Transformation (revised edition of Psychology of the Unconscious)

- 1952 Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle

- 1954 Answer to Job

- 1955 Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy

- 1957 Animus and Anima

- 1961 Memories, Dreams, Reflections

- 1963 Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice

Collected Works

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Eds. Herbert Read, Michael Fordham, Gerhard Adler. Executive ed. W. McGuire. Trans R.F.C. Hull. London: Routledge Kegan Paul (1953-1980).

- 1. Psychiatric Studies (1902–06)

- 2. Experimental Researches (1904-10) (trans L. Stein and D. Riviere)

- 3. Psychogenesis of Mental Disease (1907-14; 1919-58)

- 4. Freud and Psychoanalysis (1906-14; 1916-30)

- 5. Symbols of Transformation (1911-12; 1952)

- 6. Psychological Types (1921)

- 7. Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (1912-28)

- 8. Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (1916-52)

- 9.1 Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1934-55)

- 9.2 Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self (1951)

- 10. Civilization in Transition (1918-1959)

- 11. Psychology and Religion: West and East (1932-52)

- 12. Psychology and Alchemy (1936-44)

- 13. Alchemical Studies (1919-45):

- 14. Mysterium Coniunctionis (1955–56):

- 15. Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature (1929-1941)

- 16. The Practice of Psychotherapy (1921-25)

- 17. The Development of Personality (1910; 1925-43)

- 18. The Symbolic Life: Miscellaneous Writings

- 19. General Bibliography

- 20. General Index

Supplementary volumes

- A. The Zofingia Lectures

- B. Psychology of the Unconscious (trans. Beatrice M. Hinckle)

Seminars

- Analytical Psychology (1925)

- Dream Analysis (1928-30)[153]

- Visions (1930-34)

- The Kundalini Yoga (1932)

- Nietzsche’s Zarathustra (1934-39)

- Children's Dreams (1936-1940)