| Australopithecus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Australopithecus afarensis reconstruction, San Diego Museum of Man | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | †Australopithecina |

| Genus: | †Australopithecus R.A. Dart, 1925 |

| Type species | |

| †Australopithecus africanus

Dart, 1925

| |

| Subgroups | |

|

Also called Praeanthropus

Cladistically included genera (traditionally sometimes excluded): | |

Australopithecus, from Latin australis, meaning 'southern', and Greek πίθηκος (pithekos), meaning 'ape', informal australopithecine or australopith (although the term australopithecine has a broader meaning as a member of the subtribe Australopithecina, which includes this genus as well as the Paranthropus, Kenyanthropus, Ardipithecus, and Praeanthropus genera) is a 'genus' of hominins. From paleontological and archaeological evidence, the genus Australopithecus apparently evolved in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago before spreading throughout the continent and eventually becoming extinct two million years ago. Australopithecus is not literally extinct (in the sense of having no living descendants) as the Kenyanthropus, Paranthropus and Homo genera probably emerged as sister of a late Australopithecus species such as A. Africanus and/or A. Sediba. During that time, a number of australopithecine species emerged, including Australopithecus afarensis, A. africanus, A. anamensis, A. bahrelghazali, A. deyiremeda (proposed), A. garhi, and A. sediba.

For some hominid species of this time – A. robustus, A. boisei and A. aethiopicus – some debate exists whether they truly constitute members of the genus Australopithecus. If so, they would be considered 'robust australopiths', while the others would be 'gracile australopiths'. However, if these more robust species do constitute their own genus, they would be under the genus name Paranthropus, a genus described by Robert Broom when the first discovery was made in 1938, which makes these species P. robustus, P. boisei and P. aethiopicus.

Australopithecus species played a significant part in human evolution, the genus Homo being derived from Australopithecus at some time after three million years ago. In addition, they were the first hominids to possess certain genes, known as the duplicated SRGAP2, which increased the length and ability of neurons in the brain. One of the australopith species evolved into the genus Homo in Africa around two million years ago (e.g. Homo habilis), and eventually modern humans, H. sapiens sapiens.

In January 2019, scientists reported that Australopithecus sediba is distinct from, but shares anatomical similarities to, both the older Australopithecus africanus, and the younger Homo habilis.

Evolution

Gracile australopiths shared several traits with modern apes and humans, and were widespread throughout Eastern and Northern Africa around 3.5 million years ago. The earliest evidence of fundamentally bipedal hominids can be observed at the site of Laetoli in Tanzania.

This site contains hominid footprints that are remarkably similar to

those of modern humans and have been dated to as old as 3.6 million

years.

The footprints have generally been classified as australopith, as they

are the only form of prehuman hominins known to have existed in that

region at that time.

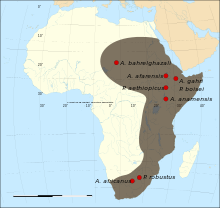

Map of the fossil sites of the early australopithecines in Africa

Australopithecus anamensis, A. afarensis, and A. africanus are among the most famous of the extinct hominins. A. africanus was once considered to be ancestral to the genus Homo (in particular Homo erectus). However, fossils assigned to the genus Homo have been found that are older than A. africanus. Thus, the genus Homo either split off from the genus Australopithecus at an earlier date (the latest common ancestor being either A. afarensis or an even earlier form, possibly Kenyanthropus), or both developed from a yet possibly unknown common ancestor independently.

According to the Chimpanzee Genome Project, the human (Ardipithecus, Australopithecus and Homo) and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes and Pan paniscus)

lineages diverged from a common ancestor about five to six million

years ago, assuming a constant rate of evolution. It is theoretically

more likely for evolution to happen more slowly, as opposed to more

quickly, from the date suggested by a gene clock (the result of which is

given as a youngest common ancestor, i.e., the latest possible date of divergence.) However, hominins discovered more recently are somewhat older than the presumed rate of evolution would suggest.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis, commonly called "Toumai", is about seven million years old and Orrorin tugenensis

lived at least six million years ago. Since little is known of them,

they remain controversial among scientists since the molecular clock in

humans has determined that humans and chimpanzees had a genetic split at

least a million years later. One theory suggests that the human and

chimpanzee lineages diverged somewhat at first, then some populations

interbred around one million years after diverging.

Morphology

The brains of most species of Australopithecus were roughly 35% of the size of a modern human brain. Most species of Australopithecus

were diminutive and gracile, usually standing 1.2 to 1.4 m (3 ft 11 in

to 4 ft 7 in) tall. In several variations is a considerable degree of sexual dimorphism, males being larger than females.

According to one scholar, A. Zihlman, Australopithecus body proportions closely resemble those of bonobos (Pan paniscus), leading evolutionary biologists such as Jeremy Griffith to suggest that bonobos may be phenotypically similar to Australopithecus.

Furthermore, thermoregulatory models suggest that Australopithecus

species were fully hair covered, more like chimpanzees and bonobos, and

unlike humans.

Modern humans do not display the same degree of sexual dimorphism as Australopithecus appears to have. In modern populations, males are on average a mere 15% larger than females, while in Australopithecus,

males could be up to 50% larger than females. New research suggests,

however, that australopithecines exhibited a lesser degree of sexual

dimorphism than these figures suggest, but the issue is not settled.

Species variations

Opinions differ as to whether the species A. aethiopicus, A. boisei, and A. robustus should be included within the genus Australopithecus, and no current consensus exists as to whether they should be placed in a distinct genus, Paranthropus, which is suggested to have developed from the ancestral Australopithecus line.

Until the last half-decade, the majority of the scientific community

included all the species shown in the box at the top of this article in a

single genus. The postulated genus Paranthropus was morphologically distinct from Australopithecus,

and its specialized morphology implies that its behaviour may have been

quite different from that of its ancestors, although it has been

suggested that the distinctive features of A. aethiopicus, A. boisei, and A. robustus may have evolved independently.

Evolutionary role

The fossil record seems to indicate that Australopithecus is the common ancestor of the distinct group of hominids now called Paranthropus (the "robust australopiths"), and most likely the genus Homo,

which includes modern humans. Although the intelligence of these early

hominids was likely no more sophisticated than in modern apes, the

bipedal stature is the key element that distinguishes the group from

previous primates, which were quadrupeds. The morphology of Australopithecus upset what scientists previously believed — namely, that strongly increased brain size had preceded bipedalism.

If A. afarensis was the definite hominid that left the footprints at Laetoli, that strengthens the notion that A. afarensis

had a small brain, but was a biped. Fossil evidence such as this makes

it clear that bipedalism far predated large brains. However, it remains a

matter of controversy as to how bipedalism first emerged (several

concepts are still being studied). The advantages of bipedalism were

that it left the hands free to grasp objects (e.g., carry food and

young), and allowed the eyes to look over tall grasses for possible food

sources or predators. However, many anthropologists argue that these

advantages were not large enough to cause the emergence of bipedalism.

A recent study of primate evolution and morphology noted that all

apes, both modern and fossil, show skeletal adaptations to erect

posture of the trunk, and that fossils such as Orrorin tugenensis

indicate bipedalism around six million years ago, around the time of

the split between humans and chimpanzees indicated by genetic studies.

This suggested that erect, straight-legged walking originated as an

adaptation to tree-dwelling. Studies of modern orangutans in Sumatra

have shown that these apes use four legs when walking on large, stable

branches, and swing underneath slightly smaller branches, but are

bipedal and keep their legs very straight when walking on multiple

flexible branches under 4 cm diameter, while also using their arms for

balance and additional support. This enables them to get nearer to the

edge of the tree canopy to get fruit or cross to another tree.

The ancestors of gorillas and chimpanzees

are suggested to have become more specialised in climbing vertical tree

trunks, using a bent hip and bent knee posture that matches the

knuckle-walking posture they use for ground travel. This was due to

climate changes around 11 to 12 million years ago that affected forests

in East and Central Africa, so periods occurred when openings prevented

travel through the tree canopy, and at these times, ancestral hominids

could have adapted the erect walking behaviour for ground travel. Humans

are closely related to these apes, and share features including wrist

bones apparently strengthened for knuckle-walking.

However, the view that human ancestors were knuckle-walkers is

now questioned since the anatomy and biomechanics of knuckle-walking in

chimpanzees and gorillas are different, suggesting that this ability

evolved independently after the last common ancestor with the human

lineage. Further comparative analysis with other primates suggests that these wrist-bone adaptations support a palm-based tree walking.

Radical changes in morphology took place before gracile

australopiths evolved; the pelvis structure and feet are very similar to

modern humans. The teeth have small canines, but australopiths generally evolved a larger postcanine dentition with thicker enamel.

Most species of Australopithecus were not any more adept

at tool use than modern nonhuman primates, yet modern African apes,

chimpanzees, and most recently gorillas, have been known to use simple

tools (i.e. cracking open nuts with stones and using long sticks to dig

for termites in mounds), and chimpanzees have been observed using spears (not thrown) for hunting.

For a long time, no known stone tools were associated with A. afarensis, and paleoanthropologists commonly thought that stone artifacts only dated back to about 2.5 million years ago.

However, a 2010 study suggests the hominin species ate meat by carving

animal carcasses with stone implements. This finding pushes back the

earliest known use of stone tools among hominins to about 3.4 million

years ago.

Some have argued that A. garhi used stone tools due to a loose association of this species and butchered animal remains.

Dentition

Australopithecines

have thirty two teeth, like modern humans, but with an intermediate

formation; between the great apes and humans. Their molars were

parallel, like those of great apes, and they had a slight pre-canine

diastema. But, their canines were smaller, like modern humans, and with

the teeth less interlocked than in previous hominins. In fact, in some

australopithecines the canines are shaped more like incisors.

The molars of Australopithicus fit together in much the

same way human's do, with low crowns and four low, rounded cusps used

for crushing. They have cutting edges on the crests.

Robust australopithecines (like A. boisei and A. robustus) had larger cheek, or buccal, teeth than the smaller – or gracile – species (like A. afarensis and A. africanus). It is possible that they had more tough, fibrous plant material in their diets while the smaller species of Australopithecus

had more meat. But it is also possibly due to their generally larger

build requiring more food. Their larger molars do support a slightly

different diet, including some hard food.

Australopithecines also had thick enamel, like those in genus Homo,

while other great apes have markedly thinner enamel. One explanation

for the thicker enamel is that these hominins were living more on the

ground than in the trees and were foraging for tubers, nuts, and cereal

grains. They would also have been eating a lot of gritty dirt with the

food, which would wear at enamel, so thicker enamel would be

advantageous. Or, it could simply indicate a change in diet. Robust

australopithecines wore their molar surfaces down flat, unlike the more

gracile species, who kept their crests, which certainly seems to suggest

a different diet. The gracile Australopithecus had larger

incisors, which indicates tearing and more meat in the diet, likely

scavenged. The wear patterns on the tooth surfaces support a largely

herbivorous diet.

When we examine the buccal microwear patterns on the teeth of A. afarensis and A. anamensis, we see that A. afarensis did not consume a lot of grasses or seeds, but rather ate fruits and leaves, but A. anamensis did eat grasses and seeds in addition to fruits and leaves.

Diet

Artistic interpretation of Australopithecus afarensis

In a 1979 preliminary microwear study of Australopithecus fossil teeth, anthropologist Alan Walker theorized that robust australopiths were largely frugivorous. Australopithecus

species mainly ate fruit, vegetables, small lizards, and tubers. Much

research has focused on a comparison between the South African species A. africanus and Paranthropus robustus. Early analyses of dental microwear in these two species showed, compared to P. robustus, A. africanus had fewer microwear features and more scratches as opposed to pits on its molar wear facets.

These observations have been interpreted as evidence that P. robustus may have fed on hard and brittle foods, such as some nuts and seeds.

More recently, new analyses based on three-dimensional renderings of

wear facets have confirmed earlier work, but have also suggested that P. robustus ate hard foods primarily as a fallback resource, while A. africanus ate more mechanically tough foods. A recent study looking at enamel fractures suggests A. africanus actually ate more hard foods than P. robustus, with double the frequency of antemortem chips.

In 1992, trace-element studies of the strontium/calcium ratios in

robust australopith fossils suggested the possibility of animal

consumption, as they did in 1994 using stable carbon isotopic analysis.

In 2005, fossils of animal bones with butchery marks dating 2.6

million years old were found at the site of Gona, Ethiopia. This implies

meat consumption by at least one of three species of hominins occurring

around that time: A. africanus, A. garhi, and/or P. aethiopicus.

In 2010, fossils of butchered animal bones dated 3.4 million

years old were found in Ethiopia, close to regions where australopith

fossils were found.

A study in 2018 found non-carious cervical lesions, caused by acid erosion, on the teeth of A. africanus suggesting the individual ate a lot of acidic fruits.

History of study

The type specimen for genus Australopithecus was discovered in 1924, in a lime quarry by workers at Taung, South Africa. The specimen was studied by the Australian anatomist Raymond Dart, who was then working at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The fossil skull was from a three-year-old bipedal primate that he named Australopithecus africanus. The first report was published in Nature

in February 1925. Dart realised that the fossil contained a number of

humanoid features, and so, he came to the conclusion that this was an

early ancestor of humans. Later, Scottish paleontologist Robert Broom and Dart set about to search for more early hominin specimens, and at several sites they found more A. africanus remains, as well as fossils of a species Broom named Paranthropus (which would now be recognised as P. robustus). Initially, anthropologists were largely hostile to the idea that these discoveries were anything but apes, though this changed during the late 1940s.

The first australopithecine discovered in eastern Africa was a skull belonging to an A. boisei that was excavated in 1959 in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania by Mary Leakey.

Since then, the Leakey family have continued to excavate the gorge,

uncovering further evidence for australopithecines, as well as for Homo habilis and Homo erectus. The scientific community took 20 years to widely accept Australopithecus as a member of the family tree.

Then, in 1997, an almost complete Australopithecus skeleton with skull was found in the Sterkfontein caves of Gauteng, South Africa. It is now called "Little Foot" and it is around 3.7 million years old. It was named Australopithecus prometheus which has since been placed within A. africanus. Other fossil remains found in the same cave in 2008 were named Australopithecus sediba, which lived 1.9 million years ago. A. africanus probably evolved into A. sediba, which some scientists think may have evolved into H. erectus, though this is heavily disputed.

Inconsistent taxonomy

Even though Australopithecus is classified as a "genus", several other genera appear to have emerged in it: Homo, Kenyanthropus and Paranthropus. This genus is thus regarded as an entrenched paraphyletic wastebasket taxon. Resolving this into monophyletic groupings requires extensive renaming of species in the binomial nomenclature. Possibilities are to rename Homo sapiens to Australopithecus sapiens (or even Pan sapiens), or to rename all the Australopithecus species.

Notable specimens

- KT-12/H1, an A. bahrelghazali mandibular fragment, discovered 1995 in Sahara, Chad

- AL 129-1, an A. afarensis knee joint, discovered 1973 in Hadar, Ethiopia

- Karabo, a juvenile male A. sediba, discovered in South Africa

- Laetoli footprints, preserved hominin footprints in Tanzania

- Lucy, a 40%-complete skeleton of a female A. afarensis, discovered 1974 in Hadar, Ethiopia

- Selam, remains of a three-year-old A. afarensis female, discovered in Dikika, Ethiopia

- STS 5 (Mrs. Ples), the most complete skull of an A. africanus ever found in South Africa

- STS 14, remains of an A. africanus, discovered 1947 in Sterkfontein, South Africa

- STS 71, skull of an A. africanus, discovered 1947 in Sterkfontein, South Africa

- Taung Child, skull of a young A. africanus, discovered 1924 in Taung, South Africa