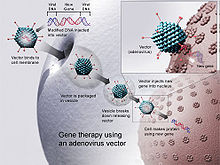

Gene therapy using an adenovirus

vector. In some cases, the adenovirus will insert the new gene into a

cell. If the treatment is successful, the new gene will make a

functional protein to treat a disease.

Gene therapy (also called human gene transfer) is a medical field which focuses on the utilization of the therapeutic delivery of nucleic acid into a patient's cells as a drug to treat disease. The first attempt at modifying human DNA was performed in 1980 by Martin Cline, but the first successful nuclear gene transfer in humans, approved by the National Institutes of Health, was performed in May 1989.

The first therapeutic use of gene transfer as well as the first direct

insertion of human DNA into the nuclear genome was performed by French Anderson in a trial starting in September 1990. It is thought to be able to cure many genetic disorders or treat them over time.

Between 1989 and December 2018, over 2,900 clinical trials were conducted, with more than half of them in phase I. As of 2017, Spark Therapeutics' Luxturna (RPE65 mutation-induced blindness) and Novartis' Kymriah (Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy) are the FDA's first approved gene therapies to enter the market. Since that time, drugs such as Novartis' Zolgensma and Alnylam's Patisiran have also received FDA approval, in addition to other companies' gene therapy drugs. Most of these approaches utilize adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) and lentiviruses for performing gene insertions, in vivo and ex vivo, respectively. ASO / siRNA approaches such as those conducted by Alnylam and Ionis Pharmaceuticals require non-viral delivery systems, and utilize alternative mechanisms for trafficking to liver cells by way of GalNAc transporters.

The introduction of CRISPR gene editing

has opened new doors for its application and utilization in gene

therapy. Solutions to medical hurdles, such as the eradication of latent

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reservoirs, may soon become a tangible reality.

Not all medical procedures that introduce alterations to a patient's genetic makeup can be considered gene therapy. Bone marrow transplantation and organ transplants in general have been found to introduce foreign DNA into patients. Gene therapy is defined by the precision of the procedure and the intention of direct therapeutic effect.

Background

Gene therapy was conceptualized in 1972, by authors who urged caution before commencing human gene therapy studies.

The first attempt, an unsuccessful one, at gene therapy (as well

as the first case of medical transfer of foreign genes into humans not

counting organ transplantation) was performed by Martin Cline on 10 July 1980.

Cline claimed that one of the genes in his patients was active six

months later, though he never published this data or had it verified and even if he is correct, it's unlikely it produced any significant beneficial effects treating beta-thalassemia.

After extensive research on animals throughout the 1980s and a

1989 bacterial gene tagging trial on humans, the first gene therapy

widely accepted as a success was demonstrated in a trial that started on

14 September 1990, when Ashi DeSilva was treated for ADA-SCID.

The first somatic treatment that produced a permanent genetic

change was initiated in 1993. The goal was to cure malignant brain

tumors by using recombinant DNA to transfer a gene making the tumor

cells sensitive to a drug that in turn would cause the tumor cells to

die.

Gene therapy is a way to fix a genetic problem at its source. The polymers are either translated into proteins, interfere with target gene expression, or possibly correct genetic mutations.

The most common form uses DNA that encodes a functional, therapeutic gene to replace a mutated gene. The polymer molecule is packaged within a "vector", which carries the molecule inside cells.

Early clinical failures led to dismissals of gene therapy.

Clinical successes since 2006 regained researchers' attention, although

as of 2014, it was still largely an experimental technique. These include treatment of retinal diseases Leber's congenital amaurosis and choroideremia, X-linked SCID, ADA-SCID, adrenoleukodystrophy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), multiple myeloma, haemophilia, and Parkinson's disease. Between 2013 and April 2014, US companies invested over $600 million in the field.

The first commercial gene therapy, Gendicine, was approved in China in 2003 for the treatment of certain cancers. In 2011 Neovasculgen was registered in Russia as the first-in-class gene-therapy drug for treatment of peripheral artery disease, including critical limb ischemia.

In 2012 Glybera, a treatment for a rare inherited disorder, lipoprotein lipase deficiency became the first treatment to be approved for clinical use in either Europe or the United States after its endorsement by the European Commission.

Following early advances in genetic engineering

of bacteria, cells, and small animals, scientists started considering

how to apply it to medicine. Two main approaches were considered –

replacing or disrupting defective genes. Scientists focused on diseases caused by single-gene defects, such as cystic fibrosis, haemophilia, muscular dystrophy, thalassemia, and sickle cell anemia. Glybera treats one such disease, caused by a defect in lipoprotein lipase.

DNA must be administered, reach the damaged cells, enter the cell and either express or disrupt a protein. Multiple delivery techniques have been explored. The initial approach incorporated DNA into an engineered virus to deliver the DNA into a chromosome. Naked DNA approaches have also been explored, especially in the context of vaccine development.

Generally, efforts focused on administering a gene that causes a

needed protein to be expressed. More recently, increased understanding

of nuclease function has led to more direct DNA editing, using techniques such as zinc finger nucleases and CRISPR.

The vector incorporates genes into chromosomes. The expressed nucleases

then knock out and replace genes in the chromosome. As of 2014 these approaches involve removing cells from patients, editing a chromosome and returning the transformed cells to patients.

Gene editing is a potential approach to alter the human genome to treat genetic diseases, viral diseases, and cancer. As of 2016 these approaches were still years from being medicine.

A duplex of crRNA and tracrRNA

acts as guide RNA to introduce a specifically located gene modification

based on the RNA 5’ upstream of the crRNA. Cas9 binds the tracrRNA and

needs a DNA binding sequence (5’NGG3’), which is called protospacer

adjacent motif (PAM). After binding, Cas9 introduces a DNA double strand

break, which is then followed by gene modification via homologous

recombination (HDR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

Cell types

Gene therapy may be classified into two types:

Somatic

In somatic cell gene therapy (SCGT), the therapeutic genes are transferred into any cell other than a gamete, germ cell, gametocyte, or undifferentiated stem cell. Any such modifications affect the individual patient only, and are not inherited by offspring. Somatic gene therapy represents mainstream basic and clinical research, in which therapeutic DNA (either integrated in the genome or as an external episome or plasmid) is used to treat disease.

Over 600 clinical trials utilizing SCGT are underway in the US. Most focus on severe genetic disorders, including immunodeficiencies, haemophilia, thalassaemia, and cystic fibrosis.

Such single gene disorders are good candidates for somatic cell

therapy. The complete correction of a genetic disorder or the

replacement of multiple genes is not yet possible. Only a few of the

trials are in the advanced stages.

Germline

In germline gene therapy (GGT), germ cells (sperm or egg cells)

are modified by the introduction of functional genes into their

genomes. Modifying a germ cell causes all the organism's cells to

contain the modified gene. The change is therefore heritable and passed on to later generations. Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, Switzerland, and the Netherlands

prohibit GGT for application in human beings, for technical and ethical

reasons, including insufficient knowledge about possible risks to

future generations and higher risks versus SCGT.

The US has no federal controls specifically addressing human genetic

modification (beyond FDA regulations for therapies in general).

Vectors

The delivery of DNA into cells can be accomplished by multiple methods. The two major classes are recombinant viruses (sometimes called biological nanoparticles or viral vectors) and naked DNA or DNA complexes (non-viral methods).

Viruses

In order to replicate, viruses

introduce their genetic material into the host cell, tricking the

host's cellular machinery into using it as blueprints for viral

proteins. Retroviruses

go a stage further by having their genetic material copied into the

genome of the host cell. Scientists exploit this by substituting a

virus's genetic material with therapeutic DNA. (The term 'DNA' may be an

oversimplification, as some viruses contain RNA, and gene therapy could

take this form as well.) A number of viruses have been used for human

gene therapy, including retroviruses, adenoviruses, herpes simplex, vaccinia, and adeno-associated virus.

Like the genetic material (DNA or RNA) in viruses, therapeutic DNA can

be designed to simply serve as a temporary blueprint that is degraded

naturally or (at least theoretically) to enter the host's genome,

becoming a permanent part of the host's DNA in infected cells.

Non-viral

Non-viral methods present certain advantages over viral methods, such as large scale production and low host immunogenicity. However, non-viral methods initially produced lower levels of transfection and gene expression,

and thus lower therapeutic efficacy. Newer technologies offer promise

of solving these problems, with the advent of increased cell-specific

targeting and subcellular trafficking control.

Methods for non-viral gene therapy include the injection of naked DNA, electroporation, the gene gun, sonoporation, magnetofection, the use of oligonucleotides, lipoplexes, dendrimers, and inorganic nanoparticles.

More recent approaches, such as those performed by companies such as Ligandal,

offer the possibility of creating cell-specific targeting technologies

for a variety of gene therapy modalities, including RNA, DNA and gene

editing tools such as CRISPR. Other companies, such as Arbutus Biopharma and Arcturus Therapeutics, offer non-viral, non-cell-targeted approaches that mainly exhibit liver trophism. In more recent years, startups such as Sixfold Bio, GenEdit, and Spotlight Therapeutics

have begun to solve the non-viral gene delivery problem. Non-viral

techniques offer the possibility of repeat dosing and greater

tailorability of genetic payloads, which in the future will be more

likely to take over viral-based delivery systems.

Companies such as Editas Medicine, Intellia Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics, Casebia, Cellectis, Precision Biosciences, bluebird bio, and Sangamo

have developed non-viral gene editing techniques, however frequently

still use viruses for delivering gene insertion material following

genomic cleavage by guided nucleases. These companies focus on gene editing, and still face major delivery hurdles.

Moderna Therapeutics and CureVac focus on delivery of mRNA payloads, which are necessarily non-viral delivery problems.

Alnylam, Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals focus on delivery of siRNA (antisense oligonucleotides) for gene suppression, which also necessitate non-viral delivery systems.

In academic contexts, a number of laboratories are working on delivery of PEGylated particles, which form serum protein coronas and chiefly exhibit LDL receptor mediated uptake in cells in vivo.

Hurdles

Some of the unsolved problems include:

- Short-lived nature – Before gene therapy can become a permanent cure for a condition, the therapeutic DNA introduced into target cells must remain functional and the cells containing the therapeutic DNA must be stable. Problems with integrating therapeutic DNA into the genome and the rapidly dividing nature of many cells prevent it from achieving long-term benefits. Patients require multiple treatments.

- Immune response – Any time a foreign object is introduced into human tissues, the immune system is stimulated to attack the invader. Stimulating the immune system in a way that reduces gene therapy effectiveness is possible. The immune system's enhanced response to viruses that it has seen before reduces the effectiveness to repeated treatments.

- Problems with viral vectors – Viral vectors carry the risks of toxicity, inflammatory responses, and gene control and targeting issues.

- Multigene disorders – Some commonly occurring disorders, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, Alzheimer's disease, arthritis, and diabetes, are affected by variations in multiple genes, which complicate gene therapy.

- Some therapies may breach the Weismann barrier (between soma and germ-line) protecting the testes, potentially modifying the germline, falling afoul of regulations in countries that prohibit the latter practice.

- Insertional mutagenesis – If the DNA is integrated in a sensitive spot in the genome, for example in a tumor suppressor gene, the therapy could induce a tumor. This has occurred in clinical trials for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) patients, in which hematopoietic stem cells were transduced with a corrective transgene using a retrovirus, and this led to the development of T cell leukemia in 3 of 20 patients. One possible solution is to add a functional tumor suppressor gene to the DNA to be integrated. This may be problematic since the longer the DNA is, the harder it is to integrate into cell genomes. CRISPR technology allows researchers to make much more precise genome changes at exact locations.

- Cost – Alipogene tiparvovec or Glybera, for example, at a cost of $1.6 million per patient, was reported in 2013 to be the world's most expensive drug.

Deaths

Three patients' deaths have been reported in gene therapy trials, putting the field under close scrutiny. The first was that of Jesse Gelsinger, who died in 1999 because of immune rejection response. One X-SCID patient died of leukemia in 2003. An 18-year-old male died of systemic inflammatory response syndrome following adenovirus gene therapy in 2003. In 2007, a rheumatoid arthritis patient died from an infection; the subsequent investigation concluded that the death was not related to gene therapy.

However it is always important to remember that although deaths are

rare they can still occur and it is very possible that certain types of

gene therapy can cause certain cancers.

History

1970s and earlier

In 1972 Friedmann and Roblin authored a paper in Science titled "Gene therapy for human genetic disease?" Rogers (1970) was cited for proposing that exogenous good DNA be used to replace the defective DNA in those who suffer from genetic defects.

1980s

In 1984 a retrovirus vector system was designed that could efficiently insert foreign genes into mammalian chromosomes.

1990s

The first approved gene therapy clinical research in the US took place on 14 September 1990, at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), under the direction of William French Anderson. Four-year-old Ashanti DeSilva received treatment for a genetic defect that left her with ADA-SCID,

a severe immune system deficiency. The defective gene of the patient's

blood cells was replaced by the functional variant. Ashanti's immune

system was partially restored by the therapy. Production of the missing

enzyme was temporarily stimulated, but the new cells with functional

genes were not generated. She led a normal life only with the regular

injections performed every two months. The effects were successful, but

temporary.

Cancer gene therapy was introduced in 1992/93 (Trojan et al. 1993).

The treatment of glioblastoma multiforme, the malignant brain tumor

whose outcome is always fatal, was done using a vector expressing

antisense IGF-I RNA (clinical trial approved by NIH protocol no.1602 24

November 1993,

and by the FDA in 1994). This therapy also represents the beginning of

cancer immunogene therapy, a treatment which proves to be effective due

to the anti-tumor mechanism of IGF-I antisense, which is related to

strong immune and apoptotic phenomena.

In 1992 Claudio Bordignon, working at the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, performed the first gene therapy procedure using hematopoietic stem cells as vectors to deliver genes intended to correct hereditary diseases. In 2002 this work led to the publication of the first successful gene therapy treatment for adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID). The success of a multi-center trial for treating children with SCID (severe combined immune deficiency

or "bubble boy" disease) from 2000 and 2002, was questioned when two of

the ten children treated at the trial's Paris center developed a

leukemia-like condition. Clinical trials were halted temporarily in

2002, but resumed after regulatory review of the protocol in the US, the

United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Germany.

In 1993 Andrew Gobea was born with SCID following prenatal genetic screening. Blood was removed from his mother's placenta and umbilical cord immediately after birth, to acquire stem cells. The allele that codes for adenosine deaminase

(ADA) was obtained and inserted into a retrovirus. Retroviruses and

stem cells were mixed, after which the viruses inserted the gene into

the stem cell chromosomes. Stem cells containing the working ADA gene

were injected into Andrew's blood. Injections of the ADA enzyme were

also given weekly. For four years T cells (white blood cells), produced by stem cells, made ADA enzymes using the ADA gene. After four years more treatment was needed.

Jesse Gelsinger's death in 1999 impeded gene therapy research in the US. As a result, the FDA suspended several clinical trials pending the reevaluation of ethical and procedural practices.

2000s

The modified cancer gene therapy strategy of antisense IGF-I RNA (NIH n˚ 1602)

using antisense / triple helix anti-IGF-I approach was registered in

2002 by Wiley gene therapy clinical trial - n˚ 635 and 636. The approach

has shown promising results in the treatment of six different malignant

tumors: glioblastoma, cancers of liver, colon, prostate, uterus, and

ovary (Collaborative NATO Science Programme on Gene Therapy USA, France,

Poland n˚ LST 980517 conducted by J. Trojan) (Trojan et al., 2012).

This anti-gene antisense/triple helix therapy has proven to be

efficient, due to the mechanism stopping simultaneously IGF-I expression

on translation and transcription levels, strengthening anti-tumor

immune and apoptotic phenomena.

2002

Sickle-cell disease can be treated in mice. The mice – which have essentially the same defect that causes human cases – used a viral vector to induce production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which normally ceases to be produced shortly after birth. In humans, the use of hydroxyurea

to stimulate the production of HbF temporarily alleviates sickle cell

symptoms. The researchers demonstrated this treatment to be a more

permanent means to increase therapeutic HbF production.

A new gene therapy approach repaired errors in messenger RNA derived from defective genes. This technique has the potential to treat thalassaemia, cystic fibrosis and some cancers.

Researchers created liposomes 25 nanometers across that can carry therapeutic DNA through pores in the nuclear membrane.

2003

In 2003 a research team inserted genes into the brain for the first time. They used liposomes coated in a polymer called polyethylene glycol, which unlike viral vectors, are small enough to cross the blood–brain barrier.

Short pieces of double-stranded RNA (short, interfering RNAs or siRNAs)

are used by cells to degrade RNA of a particular sequence. If a siRNA

is designed to match the RNA copied from a faulty gene, then the

abnormal protein product of that gene will not be produced.

Gendicine is a cancer gene therapy that delivers the tumor suppressor gene p53 using an engineered adenovirus. In 2003, it was approved in China for the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

2006

In March researchers announced the successful use of gene therapy to treat two adult patients for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, a disease which affects myeloid cells and damages the immune system. The study is the first to show that gene therapy can treat the myeloid system.

In May a team reported a way to prevent the immune system from rejecting a newly delivered gene. Similar to organ transplantation, gene therapy has been plagued by this problem. The immune system

normally recognizes the new gene as foreign and rejects the cells

carrying it. The research utilized a newly uncovered network of genes

regulated by molecules known as microRNAs.

This natural function selectively obscured their therapeutic gene in

immune system cells and protected it from discovery. Mice infected with

the gene containing an immune-cell microRNA target sequence did not

reject the gene.

In August scientists successfully treated metastatic melanoma in two patients using killer T cells genetically retargeted to attack the cancer cells.

In November researchers reported on the use of VRX496, a gene-based immunotherapy for the treatment of HIV that uses a lentiviral vector to deliver an antisense gene against the HIV envelope. In a phase I clinical trial, five subjects with chronic HIV infection who had failed to respond to at least two antiretroviral regimens were treated. A single intravenous infusion of autologous CD4

T cells genetically modified with VRX496 was well tolerated. All

patients had stable or decreased viral load; four of the five patients

had stable or increased CD4 T cell counts. All five patients had stable

or increased immune response to HIV antigens and other pathogens. This was the first evaluation of a lentiviral vector administered in a US human clinical trial.

2007

In May researchers announced the first gene therapy trial for inherited retinal disease. The first operation was carried out on a 23-year-old British male, Robert Johnson, in early 2007.

2008

Leber's congenital amaurosis is an inherited blinding disease caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene. The results of a small clinical trial in children were published in April. Delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus

(AAV) carrying RPE65 yielded positive results. In May two more groups

reported positive results in independent clinical trials using gene

therapy to treat the condition. In all three clinical trials, patients

recovered functional vision without apparent side-effects.

2009

In September researchers were able to give trichromatic vision to squirrel monkeys. In November 2009, researchers halted a fatal genetic disorder called adrenoleukodystrophy in two children using a lentivirus vector to deliver a functioning version of ABCD1, the gene that is mutated in the disorder.

2010s

2010

An April paper reported that gene therapy addressed achromatopsia (color blindness) in dogs by targeting cone

photoreceptors. Cone function and day vision were restored for at least

33 months in two young specimens. The therapy was less efficient for

older dogs.

In September it was announced that an 18-year-old male patient in France with beta-thalassemia major had been successfully treated. Beta-thalassemia major is an inherited blood disease in which beta haemoglobin is missing and patients are dependent on regular lifelong blood transfusions. The technique used a lentiviral vector to transduce the human ß-globin gene into purified blood and marrow cells obtained from the patient in June 2007.

The patient's haemoglobin levels were stable at 9 to 10 g/dL. About a

third of the hemoglobin contained the form introduced by the viral

vector and blood transfusions were not needed. Further clinical trials were planned. Bone marrow transplants are the only cure for thalassemia, but 75% of patients do not find a matching donor.

Cancer immunogene therapy using modified antigene,

antisense/triple helix approach was introduced in South America in

2010/11 in La Sabana University, Bogota (Ethical Committee 14 December

2010, no P-004-10). Considering the ethical aspect of gene diagnostic

and gene therapy targeting IGF-I, the IGF-I expressing tumors i.e. lung

and epidermis cancers were treated (Trojan et al. 2016).

2011

In 2007 and 2008, a man (Timothy Ray Brown) was cured of HIV by repeated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with double-lta-32 mutation which disables the CCR5 receptor. This cure was accepted by the medical community in 2011. It required complete ablation of existing bone marrow, which is very debilitating.

In August two of three subjects of a pilot study were confirmed to have been cured from chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The therapy used genetically modified T cells to attack cells that expressed the CD19 protein to fight the disease.

In 2013, the researchers announced that 26 of 59 patients had achieved

complete remission and the original patient had remained tumor-free.

Human HGF plasmid DNA therapy of cardiomyocytes is being examined as a potential treatment for coronary artery disease as well as treatment for the damage that occurs to the heart after myocardial infarction.

In 2011 Neovasculgen was registered in Russia as the first-in-class gene-therapy drug for treatment of peripheral artery disease, including critical limb ischemia; it delivers the gene encoding for VEGF. Neovasculogen is a plasmid encoding the CMV promoter and the 165 amino acid form of VEGF.

2012

The FDA approved Phase 1 clinical trials on thalassemia major patients in the US for 10 participants in July. The study was expected to continue until 2015.

In July 2012, the European Medicines Agency recommended approval of a gene therapy treatment for the first time in either Europe or the United States. The treatment used Alipogene tiparvovec (Glybera) to compensate for lipoprotein lipase deficiency, which can cause severe pancreatitis. The recommendation was endorsed by the European Commission in November 2012 and commercial rollout began in late 2014. Alipogene tiparvovec was expected to cost around $1.6 million per treatment in 2012, revised to $1 million in 2015, making it the most expensive medicine in the world at the time. As of 2016, only the patients treated in clinical trials and a patient who paid the full price for treatment have received the drug.

In December 2012, it was reported that 10 of 13 patients with multiple myeloma were in remission "or very close to it" three months after being injected with a treatment involving genetically engineered T cells to target proteins NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1, which exist only on cancerous myeloma cells.

2013

In March researchers reported that three of five adult subjects who had acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) had been in remission for five months to two years after being treated with genetically modified T cells which attacked cells with CD19 genes on their surface, i.e. all B-cells,

cancerous or not. The researchers believed that the patients' immune

systems would make normal T-cells and B-cells after a couple of months.

They were also given bone marrow. One patient relapsed and died and one

died of a blood clot unrelated to the disease.

Following encouraging Phase 1 trials, in April, researchers

announced they were starting Phase 2 clinical trials (called CUPID2 and

SERCA-LVAD) on 250 patients at several hospitals to combat heart disease. The therapy was designed to increase the levels of SERCA2, a protein in heart muscles, improving muscle function. The FDA granted this a Breakthrough Therapy Designation to accelerate the trial and approval process. In 2016 it was reported that no improvement was found from the CUPID 2 trial.

In July researchers reported promising results for six children

with two severe hereditary diseases had been treated with a partially

deactivated lentivirus to replace a faulty gene and after 7–32 months.

Three of the children had metachromatic leukodystrophy, which causes children to lose cognitive and motor skills. The other children had Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, which leaves them to open to infection, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Follow up trials with gene therapy on another six children with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome were also reported as promising.

In October researchers reported that two children born with adenosine deaminase severe combined immunodeficiency disease (ADA-SCID)

had been treated with genetically engineered stem cells 18 months

previously and that their immune systems were showing signs of full

recovery. Another three children were making progress. In 2014 a further 18 children with ADA-SCID were cured by gene therapy. ADA-SCID children have no functioning immune system and are sometimes known as "bubble children."

Also in October researchers reported that they had treated six

hemophilia sufferers in early 2011 using an adeno-associated virus.

Over two years later all six were producing clotting factor.

2014

In January researchers reported that six choroideremia patients had been treated with adeno-associated virus with a copy of REP1. Over a six-month to two-year period all had improved their sight. By 2016, 32 patients had been treated with positive results and researchers were hopeful the treatment would be long-lasting. Choroideremia is an inherited genetic eye disease with no approved treatment, leading to loss of sight.

In March researchers reported that 12 HIV patients had been

treated since 2009 in a trial with a genetically engineered virus with a

rare mutation (CCR5 deficiency) known to protect against HIV with promising results.

Clinical trials of gene therapy for sickle cell disease were started in 2014.

In February LentiGlobin BB305, a gene therapy treatment undergoing clinical trials for treatment of beta thalassemia

gained FDA "breakthrough" status after several patients were able to

forgo the frequent blood transfusions usually required to treat the

disease.

In March researchers delivered a recombinant gene encoding a broadly neutralizing antibody into monkeys infected with simian HIV; the monkeys' cells produced the antibody,

which cleared them of HIV. The technique is named immunoprophylaxis by

gene transfer (IGT). Animal tests for antibodies to ebola, malaria,

influenza, and hepatitis were underway.

In March, scientists, including an inventor of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna,

urged a worldwide moratorium on germline gene therapy, writing

"scientists should avoid even attempting, in lax jurisdictions, germline

genome modification for clinical application in humans" until the full

implications "are discussed among scientific and governmental

organizations".

In October, researchers announced that they had treated a baby

girl, Layla Richards, with an experimental treatment using donor T-cells

genetically engineered using TALEN to attack cancer cells. One year after the treatment she was still free of her cancer (a highly aggressive form of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [ALL]).

Children with highly aggressive ALL normally have a very poor prognosis

and Layla's disease had been regarded as terminal before the treatment.

In December, scientists of major world academies called for a moratorium on inheritable human genome edits, including those related to CRISPR-Cas9 technologies but that basic research including embryo gene editing should continue.

2016

In April the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency endorsed a gene therapy treatment called Strimvelis and the European Commission approved it in June. This treats children born with adenosine deaminase deficiency and who have no functioning immune system. This was the second gene therapy treatment to be approved in Europe.

In October, Chinese scientists reported they had started a trial

to genetically modify T-cells from 10 adult patients with lung cancer

and reinject the modified T-cells back into their bodies to attack the

cancer cells. The T-cells had the PD-1 protein (which stops or slows the immune response) removed using CRISPR-Cas9.

A 2016 Cochrane systematic review looking at data from four trials on topical cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

(CFTR) gene therapy does not support its clinical use as a mist inhaled

into the lungs to treat cystic fibrosis patients with lung infections.

One of the four trials did find weak evidence that liposome-based CFTR

gene transfer therapy may lead to a small respiratory improvement for

people with CF. This weak evidence is not enough to make a clinical

recommendation for routine CFTR gene therapy.

2017

In February Kite Pharma announced results from a clinical trial of CAR-T cells in around a hundred people with advanced Non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In March, French scientists reported on clinical research of gene therapy to treat sickle-cell disease.

In August, the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Tisagenlecleucel is an adoptive cell transfer therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; T cells from a person with cancer are removed, genetically engineered to make a specific T-cell receptor

(a chimeric T cell receptor, or "CAR-T") that reacts to the cancer, and

are administered back to the person. The T cells are engineered to

target a protein called CD19

that is common on B cells. This is the first form of gene therapy to be

approved in the United States. In October, a similar therapy called axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In December the results of using an adeno-associated virus with blood clotting factor VIII to treat nine haemophilia A

patients were published. Six of the seven patients on the high dose

regime increased the level of the blood clotting VIII to normal levels.

The low and medium dose regimes had no effect on the patient's blood

clotting levels.

In December, the FDA approved Luxturna, the first in vivo gene therapy, for the treatment of blindness due to Leber's congenital amaurosis. The price of this treatment was 850,000 US dollars for both eyes.

2018

A need was identified for high quality randomised controlled trials assessing the risks and benefits involved with gene therapy for people with sickle cell disease.

2019

In February, medical scientists working with Sangamo Therapeutics, headquartered in Richmond, California, announced the first ever "in body" human gene editing therapy to permanently alter DNA - in a patient with Hunter Syndrome. Clinical trials by Sangamo involving gene editing using Zinc Finger Nuclease (ZFN) are ongoing.

In May, the FDA approved Zolgensma for treating spinal muscular atrophy

in children under 2 years. The list price of Zolgensma was set at

$2.125 million per dose, making it the most expensive drug ever.

In June, the EMA approved Zynteglo for treating beta thalassemia for patients 12 years or older.

In July, Allergan and Editas Medicine announced phase 1/2 clinical trial of AGN-151587 for the treatment of Leber congenital amaurosis 10. It will be the world's first in vivo study of a CRISPR-based human gene editing therapy, where the editing takes place inside the human body.

Speculative uses

Speculated uses for gene therapy include:

Gene doping

Athletes might adopt gene therapy technologies to improve their performance. Gene doping is not known to occur, but multiple gene therapies may have such effects. Kayser et al. argue that gene doping could level the playing field

if all athletes receive equal access. Critics claim that any

therapeutic intervention for non-therapeutic/enhancement purposes

compromises the ethical foundations of medicine and sports.

Human genetic engineering

Genetic engineering could be used to cure diseases, but also to change physical appearance, metabolism, and even improve physical capabilities and mental faculties such as memory and intelligence. Ethical claims about germline engineering include beliefs that every fetus

has a right to remain genetically unmodified, that parents hold the

right to genetically modify their offspring, and that every child has

the right to be born free of preventable diseases.

For parents, genetic engineering could be seen as another child

enhancement technique to add to diet, exercise, education, training,

cosmetics, and plastic surgery. Another theorist claims that moral concerns limit but do not prohibit germline engineering.

A recent issue of the journal Bioethics was devoted to moral issues surrounding germline genetic engineering in people.

Possible regulatory schemes include a complete ban, provision to everyone, or professional self-regulation. The American Medical Association’s

Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs stated that "genetic

interventions to enhance traits should be considered permissible only in

severely restricted situations: (1) clear and meaningful benefits to

the fetus or child; (2) no trade-off with other characteristics or

traits; and (3) equal access to the genetic technology, irrespective of

income or other socioeconomic characteristics."

As early in the history of biotechnology as 1990, there have been scientists opposed to attempts to modify the human germline using these new tools, and such concerns have continued as technology progressed. With the advent of new techniques like CRISPR, in March 2015 a group of scientists urged a worldwide moratorium on clinical use of gene editing technologies to edit the human genome in a way that can be inherited. In April 2015, researchers sparked controversy when they reported results of basic research to edit the DNA of non-viable human embryos using CRISPR. A committee of the American National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine gave qualified support to human genome editing in 2017 once answers have been found to safety and efficiency problems "but only for serious conditions under stringent oversight."

Regulations

Regulations

covering genetic modification are part of general guidelines about

human-involved biomedical research. There are no international treaties

which are legally binding in this area, but there are recommendations

for national laws from various bodies.

The Helsinki Declaration (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects) was amended by the World Medical Association's

General Assembly in 2008. This document provides principles physicians

and researchers must consider when involving humans as research

subjects. The Statement on Gene Therapy Research initiated by the Human Genome Organization

(HUGO) in 2001 provides a legal baseline for all countries. HUGO's

document emphasizes human freedom and adherence to human rights, and

offers recommendations for somatic gene therapy, including the

importance of recognizing public concerns about such research.

United States

No

federal legislation lays out protocols or restrictions about human

genetic engineering. This subject is governed by overlapping regulations

from local and federal agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services,

the FDA and NIH's Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Researchers

seeking federal funds for an investigational new drug application,

(commonly the case for somatic human genetic engineering,) must obey

international and federal guidelines for the protection of human

subjects.

NIH serves as the main gene therapy regulator for federally

funded research. Privately funded research is advised to follow these

regulations. NIH provides funding for research that develops or enhances

genetic engineering techniques and to evaluate the ethics and quality

in current research. The NIH maintains a mandatory registry of human

genetic engineering research protocols that includes all federally

funded projects.

An NIH advisory committee published a set of guidelines on gene manipulation.

The guidelines discuss lab safety as well as human test subjects and

various experimental types that involve genetic changes. Several

sections specifically pertain to human genetic engineering, including

Section III-C-1. This section describes required review processes and

other aspects when seeking approval to begin clinical research involving

genetic transfer into a human patient.

The protocol for a gene therapy clinical trial must be approved by the

NIH's Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee prior to any clinical trial

beginning; this is different from any other kind of clinical trial.

As with other kinds of drugs, the FDA regulates the quality and

safety of gene therapy products and supervises how these products are

used clinically. Therapeutic alteration of the human genome falls under

the same regulatory requirements as any other medical treatment.

Research involving human subjects, such as clinical trials, must be reviewed and approved by the FDA and an Institutional Review Board.

Popular culture

Gene therapy is the basis for the plotline of the film I Am Legend and the TV show Will Gene Therapy Change the Human Race?. In 1994, gene therapy was a plot element in "The Erlenmeyer Flask", the first-season finale of The X-Files; it is also used in Stargate as a means of allowing humans to use Ancient technology