Martyrdom in Judaism is one of the main examples of Jews doing a kiddush Hashem, a Hebrew term which means "sanctification of [the] name".

An example of this is public self-sacrifice in accordance with Jewish

practice and identity, with the possibility of being killed for no other

reason than being Jewish. There are specific conditions in Jewish law that deal with the details of self-sacrifice, be it willing or unwilling.

The opposite or converse of kiddush Hashem is chillul Hashem ("Desecration [of] God's Name" in Hebrew) and Jews are obligated to avoid it according to Halakha (Jewish religious law). There are instances, such as when they are faced with forced conversion to another religion, when Jews should choose martyrdom and sacrifice their lives rather than commit a chillul Hashem which desecrates the honor of God. Martyrdom in Judaism is thus driven by both the desire to Sanctify God's Name concurrently and the wish to avoid the Desecration of God's Name.

In Hebrew a martyr is known as a kaddosh which means "[a] holy [one]", and martyrs are known as kedoshim meaning "holy [ones]". Thus the six million Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust are known as the Kedoshim.

Jewish history is replete with many episodes in which Jews who lived in different times and places chose to become individual and mass martyrs.

The opposite or converse of kiddush Hashem is chillul Hashem ("Desecration [of] God's Name" in Hebrew) and Jews are obligated to avoid it according to Halakha (Jewish religious law). There are instances, such as when they are faced with forced conversion to another religion, when Jews should choose martyrdom and sacrifice their lives rather than commit a chillul Hashem which desecrates the honor of God. Martyrdom in Judaism is thus driven by both the desire to Sanctify God's Name concurrently and the wish to avoid the Desecration of God's Name.

In Hebrew a martyr is known as a kaddosh which means "[a] holy [one]", and martyrs are known as kedoshim meaning "holy [ones]". Thus the six million Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust are known as the Kedoshim.

Jewish history is replete with many episodes in which Jews who lived in different times and places chose to become individual and mass martyrs.

In the Hebrew Bible

Judaism, and the Abrahamic religions such as Christianity and Islam, all draw their notions of martyrdom from the Jews' Hebrew Bible as put forth in the Torah. Christian martyrs and Islamic martyrs, known as Shahids, both draw from the original Judaic sources for the concept or Mitzvah

or commandment that calls upon one to unconditionally sacrifice one's

life for one's God and religion if called upon and if circumstances so

dictate, not to betray one's God, religion and beliefs.

Binding of Isaac

An angel prevents the sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham and Isaac, Rembrandt, 1634

The events described in the Bible known as the Binding of Isaac is the primal and archetypal example of martyrdom in the Torah. Abraham is called upon to fulfill God's commandment to slaughter his son Isaac, and Isaac to willingly submit to this and offer his life up as a korban or "sacrifice" and hence, if need be, dying as a martyr because God had so commanded it.

At the last minute God instructs Abraham to stop and to slaughter and offer up a ram instead. This was the worst of the ten tests of Abraham and the fact that Isaac was willing to give up his own life serves as a role model for all subsequent people who are called upon to sacrifice their lives for their God, religion and beliefs.

Martyrs during war

There are times that the Hebrew Bible records that the Children of Israel, also known as the Israelites, the ancestors of the Jews are instructed to wage war against their enemies in the Bible sometimes as instructed by God or their leaders or both. Examples are wars against Amalek and the Seven Nations. Such wars are known as Milkhemet Mitzvah ("war by commandment" in Hebrew, or "Holy War") and any Israelite or Jew who is killed in the course of fighting for the cause is automatically regarded as having died al Kiddush Hashem ("for Sanctifying God's Name") and is hence a Jewish martyr.

Some Biblical examples of martyrs

In Kabbalah Nadab and Abihu as described in the Book of Leviticus are consumed by fire and are sanctified by God and are examples of what God wants out of the death of martyrs. Samson in the Book of Judges is regarded as a martyr because he ultimately sacrificed his life to sanctify God's Name. In the Book of Samuel both King Saul and his sons especially Jonathan are regarded as martyrs because they sacrificed their own lives rather than being captured and humiliated by the Philistines. Zechariah ben Jehoiada a righteous priest who spoke up for justice was stoned to death on the orders of an evil king of Judah, as described in the Book of Chronicles. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego known in the Book of Daniel as Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah were thrown into a fiery furnace for disobeying the Babylonian king who had commanded his subjects to worship an idol. By a miracle they survived but are nevertheless treated as heroes who risked martyrdom.

Jewish-Babylonian War

The Jewish-Babylonian War lasted from 601 to 586 BCE. It included many battles and two sieges of Jerusalem, the Siege of Jerusalem (597 BCE) and the Siege of Jerusalem (587 BCE). The final siege resulted in the complete destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonian Empire.

Since these events took place so long ago the main records are

Biblical as well as some information gleaned from archaeology. Certainly

many thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of Jews were killed and

martyred during this period in history.

An indication of how seriously Jews and Judaism regard the scope, tragedy and impact of the destruction of the First Temple and the catastrophic impact on their land, the Kingdom of Judah, and their subsequent Babylonian Exile.

Many Jewish fast days and mourning periods were instituted and observed

since ancient times, all of which also commemorate the martyrdom of

Jews in those times:

Maccabean Revolt and Book of Maccabees

1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees recount numerous martyrdoms suffered by Jews resisting Hellenization, being executed for such crimes as observing the Sabbath, circumcising their children or refusing to eat pork or meat sacrificed to foreign gods.

During the Maccabean Revolt from 167 to 160 BCE, during at least seven wars between the Jews and the Seleucid Greeks, tens of thousands of Jews died in battle or were killed as martyrs, including some of the original Maccabees. Some of the best known Jewish martyrs of this period is the story of the woman with seven sons and Eleazar (2 Maccabees).

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah commemorates and celebrates the miracle of the triumph of the Jews against the ancient Greeks and of Judaism and Torah over classical Greek culture.

A number of Maccabees died as martyrs. Judah Maccabee, the leader of the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid Greeks was killed in the Battle of Elasa (160 BCE) and together with his men, they died as martyrs. Jonathan Maccabee was captured by a Seleucid king and executed. Eleazar Maccabee was killed in the Battle of Beth Zechariah (162 BCE). Simon Maccabee was assassinated in 135 BCE.

Jewish-Roman Wars and the destruction of the Second Temple

Martyrdom of Jews is a prominent aspect of the three major Jewish-Roman wars fought between the Jews in and out of ancient Judea and the Roman Empire in 66 CE to 136 CE that resulted in between one to two million Jewish casualties who are regarded as Jewish martyrs, such as Lulianos and Paphos.

Among other massacres Jews were massacred during the Alexandrian riots (38) and later during the Jewish revolt against Constantius Gallus (351-352).

During the Roman Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE) alone, according to Josephus, over one millions Jews died.

In Judaism and Jewish liturgy, recounting the killing of the Ten Martyrs, as taught in Midrash Eleh Ezkerah, by the Romans is considered by many a solemn high point of the Yom Kippur prayer service. The most prominent of these martyrs was Rabbi Akiva, the famous Talmudic sage.

Jews and Judaism commemorate the tragedies leading up to and including the destruction of the Second Temple, its catastrophic aftermath, and the martyrdom of so many, on the solemn fast day of Tisha B'Av.

Under the Byzantines

The Jewish revolt against Heraclius (602-628) during the era of the Byzantines resulted in the deaths and martyrdom of thousands of Jews. See the section Jewish revolt against Heraclius: Massacre of the Jews as one example.

Under Christianity

There have been times of great upheaval between Jews and Christians

and hence between Judaism and Christianity starting from the inception

of Christianity as a religion independent and apart from its Judaic

roots. This has resulted in the death and martyrdom of countless Jews

and Jewish communities dating from Roman times to the present as

outlined in the various sections of this article.

Crusades

The Crusades took place from the 11th to the 17th century during which time tens of thousands of Jews were martyred. Rabbi Ephraim of Bonn (1132-1196) chronicled the fate of Jewish communities in Germany, France and England from 1146 to 1196.

Examples of this are:

Germany

Jews burned alive for the alleged host desecration in Deggendorf, Bavaria, in 1338, and in Sternberg, Mecklenburg, in 1492; a woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

There are testimonies about these events such as the Solomon bar Simson Chronicle, the Eliezer ben Nathan Chronicle, Mainz Anonymous Chronicle. During the Rhineland massacres (1096) and the Worms massacre (1096) thousands of Jews were martyred notable amongst them was Kalonymus ben Meshullam and his sons (died 1096) and Minna of Worms (died 1096).

A special Hebrew prayer, Av HaRachamim ("Father [of] Mercy") still recited in Ashkenazi synagogues today was composed commemorating the Jewish martyrs resulting from the First Crusade (1096-1099).

The Rintfleisch massacres (1298) notably Mordechai ben Hillel (1250-1298). Erfurt massacre (1349) notably Alexander Suslin (died 1349).

England

There were massacres of Jews and their subsequent martyrdom in London, where Jacob of Orleans was murdered in 1189, and York, where notable victims were Rabbi Yom Tov of Joigny and Josce of York both of whom died in 1190. The hatred of Jews in England culminated with the Edict of Expulsion of 1290.

France

Mobs of French and German Crusaders led by Peter the Hermit ravaged Jewish communities in Speyer, Worms, and Mainz during the Rhineland massacres of 1096.

Jews in the areas of modern-day France were subject to the Crusades and many suffered martyrdom. Historian Ephraim ben Yaakov (1132-1200) describes Crusaders' massacres of Jews, including the massacre at Blois, where approximately forty Jews were killed following an accusation of ritual murder:

As they were led forth, they were told, 'You can save your lives if you will leave your religion and accept ours.' The Jews refused. They were beaten and tortured to make them accept the Christian religion, but still they refused. Rather, they encouraged each other to remain steadfast and die for the sanctification of God's Name.

Spain and the Inquisition

Jews who refused to convert to Christianity or leave Spain were called heretics would be burned to death on a stake

There were many instances of anti-Jewish violence under both the

Muslim and Christian regimes in Spain with the subsequent killing and

martyrdom of Jews, such as the. Sacks of Córdoba (1009–13), 1066 Granada massacre and the Massacre of 1391. Some examples of martyred famous Jews are Israel Alnaqua (died 1391) in Toledo and Joseph ibn Shem-Tov (died 1480).

During the Spanish Inquisition, many of those who were executed were Jews who refused to convert to Christianity. The status of those crypto-Jews who had pretended to adopt Christianity in an attempt to avoid persecution is unclear in Jewish Law that forbids Apostasy in Judaism under all circumstances. True adherents of Judaism were expelled from Spain following the Alhambra Decree of 1492 while remaining in Spain would mean death and martyrdom.

Maria Barbara Carillo (1625-1721) was burned at the stake for seeking to return to Judaism.

Blood libels and scapegoating

Jews were falsely accused of anti-Christian or anti-Muslim acts and

activities and were often scapegoated and consequently thousands of Jews

were killed and martyred over many centuries. Examples are the Brussels massacre (1370), 1910 Shiraz blood libel, Kunmadaras pogrom (1946).

During the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising was known to Jews as Gezeiras Tach VeTat,

meaning the "Decree of [years] 408 and 409" (corresponding to 1648 and

1649). Some historians estimate that between 100,000 and 500,000 Jews

were slaughtered during the Khmelnytsky Uprising from 1648 to 1658. See

the section Khmelnytsky Uprising: Jews for an outline of the discussion about the actual numbers of Jews killed by the Cossacks.

Notable martyrs of this period include Rabbi Yechiel Michel ben Eliezer (died 1648) who is also known as the Martyr of Nemirov. Rabbi Samson ben Pesah Ostropoli (died 1648) was martyred together with 300 of his followers.

Pogroms

Black Death

During the time of the Black Death in the mid-1300s, Jews in Europe were scapegoated and martyred by the thousands. Notable were the Strasbourg massacre and the Basel massacre of 1349 and the Erfurt massacre (1349).

Russian Empire

Photo believed to show the victims, mostly Jewish children, of a 1905 pogrom in Yekaterinoslav (today's Dnipro)

Jews with bodies of their comrades killed in Odessa during the Russian revolution of 1905.

The modern notion of Pogroms began mostly in the Russian Empire during the early 19th century, beginning with the Odessa pogroms.

Over more than a hundred years, tens of thousands of innocent Jewish

civilians, men women and children were massacred by rampaging mobs.

Those who were murdered in this barbaric fashion are regarded as Jewish

martyrs.

The Pogroms overlap with the beginnings of the Holocaust as well as happening during and after the Holocaust.

The 1991 Crown Heights riot in Brooklyn, New York is regarded as a latter day Pogrom that resulted in the killing of Yankel Rosenbaum and another man who looked like a Hasidic Jew.

The Holocaust

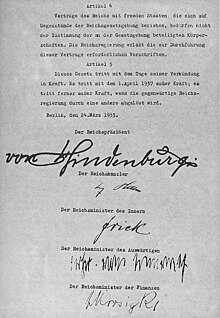

| The Holocaust | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

|

From above. 1st row: Mass graves of Bergen-Belsen after his release in April 1945. 2nd row: Jewish prisoners from Hungary newly arrived at Auschwitz

in May 1944; left image, chimneys of crematoriums II and III of

Birkenau. 3rd row: corpses in April 1945 in the already liberated Nordhausen concentration camp (left). Crematory ovens in Buchenwald with bones of German women opposed to the Nazis, April 1945 (right). 4th and last row: Auschwitz

| |

| Location | Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe |

| Description | Genocide of the European Jews |

| Date | 1939–1945 |

Attack type

| Genocide, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths |

|

| Perpetrators | Nazi Germany and its collaborators List of major perpetrators of the Holocaust |

| Motive | Antisemitism |

| Trials | Nuremberg trials, Subsequent Nuremberg trials, Trial of Adolf Eichmann, and others |

The murdered approximately six million Jews who died during the Holocaust during the period of the Second World War are regarded as martyrs by most Jewish religious scholars. In Hebrew they are referred to as kedoshim ("holy ones") who died al kiddush Hashem ("for [the] sanctification [of] God's name").

Some famous rabbis who chose martyrdom al Kiddush Hashem ("for the sanctification of God's Name") immediately before they were murdered by the Nazis include

Avraham Yitzchak Bloch, Elchonon Wasserman, Azriel Rabinowitz, Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, Menachem Ziemba, and Ben Zion Halberstam.

The State of Israel has instituted a Holocaust Memorial Day known as Yom HaShoah ("Day [of] the Holocaust") in Hebrew, to memorialize the six million Jewish martyrs murdered by the Nazis and their cohorts. There are various religious observances and liturgy. Other nations have various other Holocaust Memorial Days such as Days of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust in the United States.

Under Islam

Many Jews have perished and been martyred during the rise, and under the rule, of Islam in various countries such as the destruction of the Banu Qurayza (627 CE) in Saudi Arabia, the 1066 Granada massacre in Spain, during the Mawza Exile (1679-1680 CE) in Yemen, in Allahdad (1839 CE) in Persia, during the Farhud (1941 CE) in Iraq, in the 1945 Anti-Jewish riots in Tripolitania in Libya, the 1948 Anti-Jewish riots in Oujda and Jerada in Morocco. For more examples see Anti-Jewish pogroms by Muslims.

Muslims and the Holocaust

Haj Amin al-Husseini meeting with Adolf Hitler (28 November 1941).

November 1943 al-Husseini greeting Bosnian Waffen-SS volunteers with a Nazi salute. At right is SS General Karl-Gustav Sauberzweig.

During the Second World War, some Muslim leaders such as Amin al-Husseini colluded with the Nazis and hence contributed to the Holocaust and hence to Jewish martyrdom.

Arab-Israeli conflict

There are special Jewish memorial prayers, known as hazkaras in Hebrew, (see El Malei Rachamim), that are recited in synagogues and at special gatherings for the thousands of Jewish Israeli soldiers and civilians who are regarded as martyrs (kedoshim meaning "holy ones" in Hebrew) who have been killed in the course of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Modern Israel has instituted and dedicated a special day known as Yom HaZikaron

("Day [of] the Remembrance") in memory of those Jews killed in the

service of building up and defending the state of Israel as well as in

memory of those killed in terrorist attacks.

Victims of Antisemitism and Anti-Judaism

Jews who are murdered because of their race or religion (victims of antisemitic or anti-Judaic hate crimes), as in the 2019 Jersey City shooting, the 2019 Poway synagogue shooting, the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, the assault against the Chabad house at Nariman House in India (one of the 2008 Mumbai attacks), the 1946 Kielce pogrom, are all regarded as martyrs by most Jewish religious scholars, and they are known as kedoshim ("holy ones") in Hebrew, Jews who have died al kiddush Hashem ("for [the] sanctification [of] God's Name).