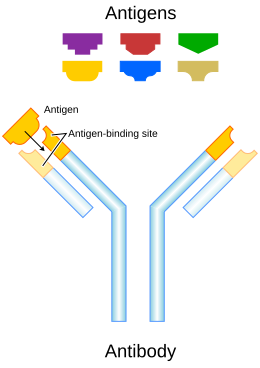

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the pathogen, called an antigen. Each tip of the "Y" of an antibody contains a paratope (analogous to a lock) that is specific for one particular epitope (analogous to a key) on an antigen, allowing these two structures to bind together with precision. Using this binding mechanism, an antibody can tag a microbe or an infected cell for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize it directly (for example, by blocking a part of a virus that is essential for its invasion).

To allow the immune system to recognize millions of different antigens, the antigen-binding sites at both tips of the antibody come in an equally wide variety. In contrast, the remainder of the antibody is relatively constant. It only occurs in a few variants, which define the antibody's class or isotype: IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, or IgM. The constant region at the trunk of the antibody includes sites involved in interactions with other components of the immune system. The class hence determines the function triggered by an antibody after binding to an antigen, in addition to some structural features. Antibodies from different classes also differ in where they are released in the body and at what stage of an immune response.

Together with B and T cells, antibodies comprise the most important part of the adaptive immune system. They occur in two forms: one that is attached to a B cell, and the other, a soluble form, that is unattached and found in extracellular fluids such as blood plasma. Initially, all antibodies are of the first form, attached to the surface of a B cell – these are then referred to as B-cell receptors (BCR). After an antigen binds to a BCR, the B cell activates to proliferate and differentiate into either plasma cells, which secrete soluble antibodies with the same paratope, or memory B cells, which survive in the body to enable long-lasting immunity to the antigen. Soluble antibodies are released into the blood and tissue fluids, as well as many secretions. Because these fluids were traditionally known as humors, antibody-mediated immunity is sometimes known as, or considered a part of, humoral immunity. The soluble Y-shaped units can occur individually as monomers, or in complexes of two to five units.

Antibodies are glycoproteins belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily. The terms antibody and immunoglobulin are often used interchangeably, though the term 'antibody' is sometimes reserved for the secreted, soluble form, i.e. excluding B-cell receptors.

Structure

Antibodies are heavy (~150 kDa) proteins of about 10 nm in size, arranged in three globular regions that roughly form a Y shape.

In humans and most mammals, an antibody unit consists of four polypeptide chains; two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains connected by disulfide bonds. Each chain is a series of domains: somewhat similar sequences of about 110 amino acids each. These domains are usually represented in simplified schematics as rectangles. Light chains consist of one variable domain VL and one constant domain CL, while heavy chains contain one variable domain VH and three to four constant domains CH1, CH2, ...

Structurally an antibody is also partitioned into two antigen-binding fragments (Fab), containing one VL, VH, CL, and CH1 domain each, as well as the crystallisable fragment (Fc), forming the trunk of the Y shape. In between them is a hinge region of the heavy chains, whose flexibility allows antibodies to bind to pairs of epitopes at various distances, to form complexes (dimers, trimers, etc.), and to bind effector molecules more easily.

In an electrophoresis test of blood proteins, antibodies mostly migrate to the last, gamma globulin fraction. Conversely, most gamma-globulins are antibodies, which is why the two terms were historically used as synonyms, as were the symbols Ig and γ. This variant terminology fell out of use due to the correspondence being inexact and due to confusion with γ heavy chains which characterize the IgG class of antibodies.

Antigen-binding site

The variable domains can also be referred to as the FV region. It is the subregion of Fab that binds to an antigen. More specifically, each variable domain contains three hypervariable regions – the amino acids seen there vary the most from antibody to antibody. When the protein folds, these regions give rise to three loops of β-strands, localized near one another on the surface of the antibody. These loops are referred to as the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), since their shape complements that of an antigen. Three CDRs from each of the heavy and light chains together form an antibody-binding site whose shape can be anything from a pocket to which a smaller antigen binds, to a larger surface, to a protrusion that sticks out into a groove in an antigen. Typically however only a few residues contribute to most of the binding energy.

The existence of two identical antibody-binding sites allows antibody molecules to bind strongly to multivalent antigen (repeating sites such as polysaccharides in bacterial cell walls, or other sites at some distance apart), as well as to form antibody complexes and larger antigen-antibody complexes. The resulting cross-linking plays a role in activating other parts of the immune system.

The structures of CDRs have been clustered and classified by Chothia et al. and more recently by North et al. and Nikoloudis et al. In the framework of the immune network theory, CDRs are also called idiotypes. According to immune network theory, the adaptive immune system is regulated by interactions between idiotypes.

Fc region

The Fc region (the trunk of the Y shape) is composed of constant domains from the heavy chains. Its role is in modulating immune cell activity: it is where effector molecules bind to, triggering various effects after the antibody Fab region binds to an antigen. Effector cells (such as macrophages or natural killer cells) bind via their Fc receptors (FcR) to the Fc region of an antibody, while the complement system is activated by binding the C1q protein complex. IgG or IgM can bind to C1q, but IgA cannot, therefore IgA does not activate the classical complement pathway.

Another role of the Fc region is to selectively distribute different antibody classes across the body. In particular, the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binds to the Fc region of IgG antibodies to transport it across the placenta, from the mother to the fetus.

Antibodies are glycoproteins, that is, they have carbohydrates (glycans) added to conserved amino acid residues. These conserved glycosylation sites occur in the Fc region and influence interactions with effector molecules.

Protein structure

The N-terminus of each chain is situated at the tip. Each immunoglobulin domain has a similar structure, characteristic of all the members of the immunoglobulin superfamily: it is composed of between 7 (for constant domains) and 9 (for variable domains) β-strands, forming two beta sheets in a Greek key motif. The sheets create a "sandwich" shape, the immunoglobulin fold, held together by a disulfide bond.

Antibody complexes

Secreted antibodies can occur as a single Y-shaped unit, a monomer. However, some antibody classes also form dimers with two Ig units (as with IgA), tetramers with four Ig units (like teleost fish IgM), or pentamers with five Ig units (like mammalian IgM, which occasionally forms hexamers as well, with six units).

Antibodies also form complexes by binding to antigen: this is called an antigen-antibody complex or immune complex. Small antigens can cross-link two antibodies, also leading to the formation of antibody dimers, trimers, tetramers, etc. Multivalent antigens (e.g., cells with multiple epitopes) can form larger complexes with antibodies. An extreme example is the clumping, or agglutination, of red blood cells with antibodies in the Coombs test to determine blood groups: the large clumps become insoluble, leading to visually apparent precipitation.

B cell receptors

The membrane-bound form of an antibody may be called a surface immunoglobulin (sIg) or a membrane immunoglobulin (mIg). It is part of the B cell receptor (BCR), which allows a B cell to detect when a specific antigen is present in the body and triggers B cell activation. The BCR is composed of surface-bound IgD or IgM antibodies and associated Ig-α and Ig-β heterodimers, which are capable of signal transduction. A typical human B cell will have 50,000 to 100,000 antibodies bound to its surface. Upon antigen binding, they cluster in large patches, which can exceed 1 micrometer in diameter, on lipid rafts that isolate the BCRs from most other cell signaling receptors. These patches may improve the efficiency of the cellular immune response. In humans, the cell surface is bare around the B cell receptors for several hundred nanometers, which further isolates the BCRs from competing influences.

Classes

Antibodies can come in different varieties known as isotypes or classes. In placental mammals there are five antibody classes known as IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM, which are further subdivided into subclasses such as IgA1, IgA2. The prefix "Ig" stands for immunoglobulin, while the suffix denotes the type of heavy chain the antibody contains: the heavy chain types α (alpha), γ (gamma), δ (delta), ε (epsilon), μ (mu) give rise to IgA, IgG, IgD, IgE, IgM, respectively. The distinctive features of each class are determined by the part of the heavy chain within the hinge and Fc region.

The classes differ in their biological properties, functional locations and ability to deal with different antigens, as depicted in the table. For example, IgE antibodies are responsible for an allergic response consisting of histamine release from mast cells, contributing to asthma. The antibody's variable region binds to allergic antigen, for example house dust mite particles, while its Fc region (in the ε heavy chains) binds to Fc receptor ε on a mast cell, triggering its degranulation: the release of molecules stored in its granules.

| Class | Subclasses | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IgA | 2 | Found in mucosal areas, such as the gut, respiratory tract and urogenital tract, and prevents colonization by pathogens. Also found in saliva, tears, and breast milk. |

| IgD | 1 | Functions mainly as an antigen receptor on B cells that have not been exposed to antigens. It has been shown to activate basophils and mast cells to produce antimicrobial factors. |

| IgE | 1 | Binds to allergens and triggers histamine release from mast cells and basophils, and is involved in allergy. Also protects against parasitic worms. |

| IgG | 4 | In its four forms, provides the majority of antibody-based immunity against invading pathogens. The only antibody capable of crossing the placenta to give passive immunity to the fetus. |

| IgM | 1 | Expressed on the surface of B cells (monomer) and in a secreted form (pentamer) with very high avidity. Eliminates pathogens in the early stages of B cell-mediated (humoral) immunity before there is sufficient IgG. |

The antibody isotype of a B cell changes during cell development and activation. Immature B cells, which have never been exposed to an antigen, express only the IgM isotype in a cell surface bound form. The B lymphocyte, in this ready-to-respond form, is known as a "naive B lymphocyte." The naive B lymphocyte expresses both surface IgM and IgD. The co-expression of both of these immunoglobulin isotypes renders the B cell ready to respond to antigen. B cell activation follows engagement of the cell-bound antibody molecule with an antigen, causing the cell to divide and differentiate into an antibody-producing cell called a plasma cell. In this activated form, the B cell starts to produce antibody in a secreted form rather than a membrane-bound form. Some daughter cells of the activated B cells undergo isotype switching, a mechanism that causes the production of antibodies to change from IgM or IgD to the other antibody isotypes, IgE, IgA, or IgG, that have defined roles in the immune system.

Light chain types

In mammals there are two types of immunoglobulin light chain, which are called lambda (λ) and kappa (κ). However, there is no known functional difference between them, and both can occur with any of the five major types of heavy chains. Each antibody contains two identical light chains: both κ or both λ. Proportions of κ and λ types vary by species and can be used to detect abnormal proliferation of B cell clones. Other types of light chains, such as the iota (ι) chain, are found in other vertebrates like sharks (Chondrichthyes) and bony fishes (Teleostei).

In animals

In most placental mammals the structure of antibodies is generally the same. Jawed fish appear to be the most primitive animals that are able to make antibodies similar to those of mammals, although many features of their adaptive immunity appeared somewhat earlier. Cartilaginous fish (such as sharks) produce heavy-chain-only antibodies (lacking light chains) which moreover feature longer chains, with five constant domains each. Camelids (such as camels, llamas, alpacas) are also notable for producing heavy-chain-only antibodies.

| Class | Types | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IgY | Found in birds and reptiles; related to mammalian IgG. | |

| IgW | Found in sharks and skates; related to mammalian IgD. |

Antibody–antigen interactions

The antibody's paratope interacts with the antigen's epitope. An antigen usually contains different epitopes along its surface arranged discontinuously, and dominant epitopes on a given antigen are called determinants.

Antibody and antigen interact by spatial complementarity (lock and key). The molecular forces involved in the Fab-epitope interaction are weak and non-specific – for example electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces. This means binding between antibody and antigen is reversible, and the antibody's affinity towards an antigen is relative rather than absolute. Relatively weak binding also means it is possible for an antibody to cross-react with different antigens of different relative affinities.

Function

The main categories of antibody action include the following:

- Neutralisation, in which neutralizing antibodies block parts of the surface of a bacterial cell or virion to render its attack ineffective

- Agglutination, in which antibodies "glue together" foreign cells into clumps that are attractive targets for phagocytosis

- Precipitation, in which antibodies "glue together" serum-soluble antigens, forcing them to precipitate out of solution in clumps that are attractive targets for phagocytosis

- Complement activation (fixation), in which antibodies that are latched onto a foreign cell encourage complement to attack it with a membrane attack complex, which leads to the following:

- Lysis of the foreign cell

- Encouragement of inflammation by chemotactically attracting inflammatory cells

More indirectly, an antibody can signal immune cells to present antibody fragments to T cells, or downregulate other immune cells to avoid autoimmunity.

Activated B cells differentiate into either antibody-producing cells called plasma cells that secrete soluble antibody or memory cells that survive in the body for years afterward in order to allow the immune system to remember an antigen and respond faster upon future exposures.

At the prenatal and neonatal stages of life, the presence of antibodies is provided by passive immunization from the mother. Early endogenous antibody production varies for different kinds of antibodies, and usually appear within the first years of life. Since antibodies exist freely in the bloodstream, they are said to be part of the humoral immune system. Circulating antibodies are produced by clonal B cells that specifically respond to only one antigen (an example is a virus capsid protein fragment). Antibodies contribute to immunity in three ways: They prevent pathogens from entering or damaging cells by binding to them; they stimulate removal of pathogens by macrophages and other cells by coating the pathogen; and they trigger destruction of pathogens by stimulating other immune responses such as the complement pathway. Antibodies will also trigger vasoactive amine degranulation to contribute to immunity against certain types of antigens (helminths, allergens).

Activation of complement

Antibodies that bind to surface antigens (for example, on bacteria) will attract the first component of the complement cascade with their Fc region and initiate activation of the "classical" complement system. This results in the killing of bacteria in two ways. First, the binding of the antibody and complement molecules marks the microbe for ingestion by phagocytes in a process called opsonization; these phagocytes are attracted by certain complement molecules generated in the complement cascade. Second, some complement system components form a membrane attack complex to assist antibodies to kill the bacterium directly (bacteriolysis).

Activation of effector cells

To combat pathogens that replicate outside cells, antibodies bind to pathogens to link them together, causing them to agglutinate. Since an antibody has at least two paratopes, it can bind more than one antigen by binding identical epitopes carried on the surfaces of these antigens. By coating the pathogen, antibodies stimulate effector functions against the pathogen in cells that recognize their Fc region.

Those cells that recognize coated pathogens have Fc receptors, which, as the name suggests, interact with the Fc region of IgA, IgG, and IgE antibodies. The engagement of a particular antibody with the Fc receptor on a particular cell triggers an effector function of that cell; phagocytes will phagocytose, mast cells and neutrophils will degranulate, natural killer cells will release cytokines and cytotoxic molecules; that will ultimately result in destruction of the invading microbe. The activation of natural killer cells by antibodies initiates a cytotoxic mechanism known as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) – this process may explain the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies used in biological therapies against cancer. The Fc receptors are isotype-specific, which gives greater flexibility to the immune system, invoking only the appropriate immune mechanisms for distinct pathogens.

Natural antibodies

Humans and higher primates also produce "natural antibodies" that are present in serum before viral infection. Natural antibodies have been defined as antibodies that are produced without any previous infection, vaccination, other foreign antigen exposure or passive immunization. These antibodies can activate the classical complement pathway leading to lysis of enveloped virus particles long before the adaptive immune response is activated. Many natural antibodies are directed against the disaccharide galactose α(1,3)-galactose (α-Gal), which is found as a terminal sugar on glycosylated cell surface proteins, and generated in response to production of this sugar by bacteria contained in the human gut. Rejection of xenotransplantated organs is thought to be, in part, the result of natural antibodies circulating in the serum of the recipient binding to α-Gal antigens expressed on the donor tissue.

Immunoglobulin diversity

Virtually all microbes can trigger an antibody response. Successful recognition and eradication of many different types of microbes requires diversity among antibodies; their amino acid composition varies allowing them to interact with many different antigens. It has been estimated that humans generate about 10 billion different antibodies, each capable of binding a distinct epitope of an antigen. Although a huge repertoire of different antibodies is generated in a single individual, the number of genes available to make these proteins is limited by the size of the human genome. Several complex genetic mechanisms have evolved that allow vertebrate B cells to generate a diverse pool of antibodies from a relatively small number of antibody genes.

Domain variability

The chromosomal region that encodes an antibody is large and contains several distinct gene loci for each domain of the antibody—the chromosome region containing heavy chain genes (IGH@) is found on chromosome 14, and the loci containing lambda and kappa light chain genes (IGL@ and IGK@) are found on chromosomes 22 and 2 in humans. One of these domains is called the variable domain, which is present in each heavy and light chain of every antibody, but can differ in different antibodies generated from distinct B cells. Differences, between the variable domains, are located on three loops known as hypervariable regions (HV-1, HV-2 and HV-3) or complementarity-determining regions (CDR1, CDR2 and CDR3). CDRs are supported within the variable domains by conserved framework regions. The heavy chain locus contains about 65 different variable domain genes that all differ in their CDRs. Combining these genes with an array of genes for other domains of the antibody generates a large cavalry of antibodies with a high degree of variability. This combination is called V(D)J recombination discussed below.

V(D)J recombination

Somatic recombination of immunoglobulins, also known as V(D)J recombination, involves the generation of a unique immunoglobulin variable region. The variable region of each immunoglobulin heavy or light chain is encoded in several pieces—known as gene segments (subgenes). These segments are called variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) segments. V, D and J segments are found in Ig heavy chains, but only V and J segments are found in Ig light chains. Multiple copies of the V, D and J gene segments exist, and are tandemly arranged in the genomes of mammals. In the bone marrow, each developing B cell will assemble an immunoglobulin variable region by randomly selecting and combining one V, one D and one J gene segment (or one V and one J segment in the light chain). As there are multiple copies of each type of gene segment, and different combinations of gene segments can be used to generate each immunoglobulin variable region, this process generates a huge number of antibodies, each with different paratopes, and thus different antigen specificities. The rearrangement of several subgenes (i.e. V2 family) for lambda light chain immunoglobulin is coupled with the activation of microRNA miR-650, which further influences biology of B-cells.

RAG proteins play an important role with V(D)J recombination in cutting DNA at a particular region. Without the presence of these proteins, V(D)J recombination would not occur.

After a B cell produces a functional immunoglobulin gene during V(D)J recombination, it cannot express any other variable region (a process known as allelic exclusion) thus each B cell can produce antibodies containing only one kind of variable chain.

Somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation

Following activation with antigen, B cells begin to proliferate rapidly. In these rapidly dividing cells, the genes encoding the variable domains of the heavy and light chains undergo a high rate of point mutation, by a process called somatic hypermutation (SHM). SHM results in approximately one nucleotide change per variable gene, per cell division. As a consequence, any daughter B cells will acquire slight amino acid differences in the variable domains of their antibody chains.

This serves to increase the diversity of the antibody pool and impacts the antibody's antigen-binding affinity. Some point mutations will result in the production of antibodies that have a weaker interaction (low affinity) with their antigen than the original antibody, and some mutations will generate antibodies with a stronger interaction (high affinity). B cells that express high affinity antibodies on their surface will receive a strong survival signal during interactions with other cells, whereas those with low affinity antibodies will not, and will die by apoptosis. Thus, B cells expressing antibodies with a higher affinity for the antigen will outcompete those with weaker affinities for function and survival allowing the average affinity of antibodies to increase over time. The process of generating antibodies with increased binding affinities is called affinity maturation. Affinity maturation occurs in mature B cells after V(D)J recombination, and is dependent on help from helper T cells.

Class switching

Isotype or class switching is a biological process occurring after activation of the B cell, which allows the cell to produce different classes of antibody (IgA, IgE, or IgG). The different classes of antibody, and thus effector functions, are defined by the constant (C) regions of the immunoglobulin heavy chain. Initially, naive B cells express only cell-surface IgM and IgD with identical antigen binding regions. Each isotype is adapted for a distinct function; therefore, after activation, an antibody with an IgG, IgA, or IgE effector function might be required to effectively eliminate an antigen. Class switching allows different daughter cells from the same activated B cell to produce antibodies of different isotypes. Only the constant region of the antibody heavy chain changes during class switching; the variable regions, and therefore antigen specificity, remain unchanged. Thus the progeny of a single B cell can produce antibodies, all specific for the same antigen, but with the ability to produce the effector function appropriate for each antigenic challenge. Class switching is triggered by cytokines; the isotype generated depends on which cytokines are present in the B cell environment.

Class switching occurs in the heavy chain gene locus by a mechanism called class switch recombination (CSR). This mechanism relies on conserved nucleotide motifs, called switch (S) regions, found in DNA upstream of each constant region gene (except in the δ-chain). The DNA strand is broken by the activity of a series of enzymes at two selected S-regions. The variable domain exon is rejoined through a process called non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) to the desired constant region (γ, α or ε). This process results in an immunoglobulin gene that encodes an antibody of a different isotype.

Specificity designations

An antibody can be called monospecific if it has specificity for the same antigen or epitope, or bispecific if they have affinity for two different antigens or two different epitopes on the same antigen. A group of antibodies can be called polyvalent (or unspecific) if they have affinity for various antigens or microorganisms. Intravenous immunoglobulin, if not otherwise noted, consists of a variety of different IgG (polyclonal IgG). In contrast, monoclonal antibodies are identical antibodies produced by a single B cell.

Asymmetrical antibodies

Heterodimeric antibodies, which are also asymmetrical antibodies, allow for greater flexibility and new formats for attaching a variety of drugs to the antibody arms. One of the general formats for a heterodimeric antibody is the "knobs-into-holes" format. This format is specific to the heavy chain part of the constant region in antibodies. The "knobs" part is engineered by replacing a small amino acid with a larger one. It fits into the "hole", which is engineered by replacing a large amino acid with a smaller one. What connects the "knobs" to the "holes" are the disulfide bonds between each chain. The "knobs-into-holes" shape facilitates antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity. Single chain variable fragments (scFv) are connected to the variable domain of the heavy and light chain via a short linker peptide. The linker is rich in glycine, which gives it more flexibility, and serine/threonine, which gives it specificity. Two different scFv fragments can be connected together, via a hinge region, to the constant domain of the heavy chain or the constant domain of the light chain. This gives the antibody bispecificity, allowing for the binding specificities of two different antigens. The "knobs-into-holes" format enhances heterodimer formation but doesn't suppress homodimer formation.

To further improve the function of heterodimeric antibodies, many scientists are looking towards artificial constructs. Artificial antibodies are largely diverse protein motifs that use the functional strategy of the antibody molecule, but aren't limited by the loop and framework structural constraints of the natural antibody. Being able to control the combinational design of the sequence and three-dimensional space could transcend the natural design and allow for the attachment of different combinations of drugs to the arms.

Heterodimeric antibodies have a greater range in shapes they can take and the drugs that are attached to the arms don't have to be the same on each arm, allowing for different combinations of drugs to be used in cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals are able to produce highly functional bispecific, and even multispecific, antibodies. The degree to which they can function is impressive given that such a change of shape from the natural form should lead to decreased functionality.

History

The first use of the term "antibody" occurred in a text by Paul Ehrlich. The term Antikörper (the German word for antibody) appears in the conclusion of his article "Experimental Studies on Immunity", published in October 1891, which states that, "if two substances give rise to two different Antikörper, then they themselves must be different". However, the term was not accepted immediately and several other terms for antibody were proposed; these included Immunkörper, Amboceptor, Zwischenkörper, substance sensibilisatrice, copula, Desmon, philocytase, fixateur, and Immunisin. The word antibody has formal analogy to the word antitoxin and a similar concept to Immunkörper (immune body in English). As such, the original construction of the word contains a logical flaw; the antitoxin is something directed against a toxin, while the antibody is a body directed against something.

The study of antibodies began in 1890 when Emil von Behring and Kitasato Shibasaburō described antibody activity against diphtheria and tetanus toxins. Von Behring and Kitasato put forward the theory of humoral immunity, proposing that a mediator in serum could react with a foreign antigen. His idea prompted Paul Ehrlich to propose the side-chain theory for antibody and antigen interaction in 1897, when he hypothesized that receptors (described as "side-chains") on the surface of cells could bind specifically to toxins – in a "lock-and-key" interaction – and that this binding reaction is the trigger for the production of antibodies. Other researchers believed that antibodies existed freely in the blood and, in 1904, Almroth Wright suggested that soluble antibodies coated bacteria to label them for phagocytosis and killing; a process that he named opsoninization.

In the 1920s, Michael Heidelberger and Oswald Avery observed that antigens could be precipitated by antibodies and went on to show that antibodies are made of protein. The biochemical properties of antigen-antibody-binding interactions were examined in more detail in the late 1930s by John Marrack. The next major advance was in the 1940s, when Linus Pauling confirmed the lock-and-key theory proposed by Ehrlich by showing that the interactions between antibodies and antigens depend more on their shape than their chemical composition. In 1948, Astrid Fagraeus discovered that B cells, in the form of plasma cells, were responsible for generating antibodies.

Further work concentrated on characterizing the structures of the antibody proteins. A major advance in these structural studies was the discovery in the early 1960s by Gerald Edelman and Joseph Gally of the antibody light chain, and their realization that this protein is the same as the Bence-Jones protein described in 1845 by Henry Bence Jones. Edelman went on to discover that antibodies are composed of disulfide bond-linked heavy and light chains. Around the same time, antibody-binding (Fab) and antibody tail (Fc) regions of IgG were characterized by Rodney Porter. Together, these scientists deduced the structure and complete amino acid sequence of IgG, a feat for which they were jointly awarded the 1972 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The Fv fragment was prepared and characterized by David Givol. While most of these early studies focused on IgM and IgG, other immunoglobulin isotypes were identified in the 1960s: Thomas Tomasi discovered secretory antibody (IgA); David S. Rowe and John L. Fahey discovered IgD; and Kimishige Ishizaka and Teruko Ishizaka discovered IgE and showed it was a class of antibodies involved in allergic reactions. In a landmark series of experiments beginning in 1976, Susumu Tonegawa showed that genetic material can rearrange itself to form the vast array of available antibodies.

Medical applications

Disease diagnosis

Detection of particular antibodies is a very common form of medical diagnostics, and applications such as serology depend on these methods. For example, in biochemical assays for disease diagnosis, a titer of antibodies directed against Epstein-Barr virus or Lyme disease is estimated from the blood. If those antibodies are not present, either the person is not infected or the infection occurred a very long time ago, and the B cells generating these specific antibodies have naturally decayed.

In clinical immunology, levels of individual classes of immunoglobulins are measured by nephelometry (or turbidimetry) to characterize the antibody profile of patient. Elevations in different classes of immunoglobulins are sometimes useful in determining the cause of liver damage in patients for whom the diagnosis is unclear. For example, elevated IgA indicates alcoholic cirrhosis, elevated IgM indicates viral hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis, while IgG is elevated in viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Autoimmune disorders can often be traced to antibodies that bind the body's own epitopes; many can be detected through blood tests. Antibodies directed against red blood cell surface antigens in immune mediated hemolytic anemia are detected with the Coombs test. The Coombs test is also used for antibody screening in blood transfusion preparation and also for antibody screening in antenatal women.

Practically, several immunodiagnostic methods based on detection of complex antigen-antibody are used to diagnose infectious diseases, for example ELISA, immunofluorescence, Western blot, immunodiffusion, immunoelectrophoresis, and magnetic immunoassay. Antibodies raised against human chorionic gonadotropin are used in over the counter pregnancy tests.

New dioxaborolane chemistry enables radioactive fluoride (18F) labeling of antibodies, which allows for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of cancer.

Disease therapy

Targeted monoclonal antibody therapy is employed to treat diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, and many forms of cancer including non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer and breast cancer.

Some immune deficiencies, such as X-linked agammaglobulinemia and hypogammaglobulinemia, result in partial or complete lack of antibodies. These diseases are often treated by inducing a short-term form of immunity called passive immunity. Passive immunity is achieved through the transfer of ready-made antibodies in the form of human or animal serum, pooled immunoglobulin or monoclonal antibodies, into the affected individual.

Prenatal therapy

Rh factor, also known as Rh D antigen, is an antigen found on red blood cells; individuals that are Rh-positive (Rh+) have this antigen on their red blood cells and individuals that are Rh-negative (Rh–) do not. During normal childbirth, delivery trauma or complications during pregnancy, blood from a fetus can enter the mother's system. In the case of an Rh-incompatible mother and child, consequential blood mixing may sensitize an Rh- mother to the Rh antigen on the blood cells of the Rh+ child, putting the remainder of the pregnancy, and any subsequent pregnancies, at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Rho(D) immune globulin antibodies are specific for human RhD antigen. Anti-RhD antibodies are administered as part of a prenatal treatment regimen to prevent sensitization that may occur when a Rh-negative mother has a Rh-positive fetus. Treatment of a mother with Anti-RhD antibodies prior to and immediately after trauma and delivery destroys Rh antigen in the mother's system from the fetus. It is important to note that this occurs before the antigen can stimulate maternal B cells to "remember" Rh antigen by generating memory B cells. Therefore, her humoral immune system will not make anti-Rh antibodies, and will not attack the Rh antigens of the current or subsequent babies. Rho(D) Immune Globulin treatment prevents sensitization that can lead to Rh disease, but does not prevent or treat the underlying disease itself.

Research applications

Specific antibodies are produced by injecting an antigen into a mammal, such as a mouse, rat, rabbit, goat, sheep, or horse for large quantities of antibody. Blood isolated from these animals contains polyclonal antibodies—multiple antibodies that bind to the same antigen—in the serum, which can now be called antiserum. Antigens are also injected into chickens for generation of polyclonal antibodies in egg yolk. To obtain antibody that is specific for a single epitope of an antigen, antibody-secreting lymphocytes are isolated from the animal and immortalized by fusing them with a cancer cell line. The fused cells are called hybridomas, and will continually grow and secrete antibody in culture. Single hybridoma cells are isolated by dilution cloning to generate cell clones that all produce the same antibody; these antibodies are called monoclonal antibodies. Polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies are often purified using Protein A/G or antigen-affinity chromatography.

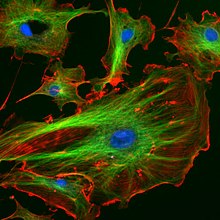

In research, purified antibodies are used in many applications. Antibodies for research applications can be found directly from antibody suppliers, or through use of a specialist search engine. Research antibodies are most commonly used to identify and locate intracellular and extracellular proteins. Antibodies are used in flow cytometry to differentiate cell types by the proteins they express; different types of cell express different combinations of cluster of differentiation molecules on their surface, and produce different intracellular and secretable proteins. They are also used in immunoprecipitation to separate proteins and anything bound to them (co-immunoprecipitation) from other molecules in a cell lysate,[96] in Western blot analyses to identify proteins separated by electrophoresis, and in immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence to examine protein expression in tissue sections or to locate proteins within cells with the assistance of a microscope. Proteins can also be detected and quantified with antibodies, using ELISA and ELISpot techniques.

Antibodies used in research are some of the most powerful, yet most problematic reagents with a tremendous number of factors that must be controlled in any experiment including cross reactivity, or the antibody recognizing multiple epitopes and affinity, which can vary widely depending on experimental conditions such as pH, solvent, state of tissue etc. Multiple attempts have been made to improve both the way that researchers validate antibodies and ways in which they report on antibodies. Researchers using antibodies in their work need to record them correctly in order to allow their research to be reproducible (and therefore tested, and qualified by other researchers). Less than half of research antibodies referenced in academic papers can be easily identified. Papers published in F1000 in 2014 and 2015 provide researchers with a guide for reporting research antibody use. The RRID paper, is co-published in 4 journals that implemented the RRIDs Standard for research resource citation, which draws data from the antibodyregistry.org as the source of antibody identifiers.

Regulations

Production and testing

Traditionally, most antibodies are produced by hybridoma cell lines through immortalization of antibody-producing cells by chemically-induced fusion with myeloma cells. In some cases, additional fusions with other lines have created "triomas" and "quadromas". The manufacturing process should be appropriately described and validated. Validation studies should at least include:

- The demonstration that the process is able to produce in good quality (the process should be validated)

- The efficiency of the antibody purification (all impurities and virus must be eliminated)

- The characterization of purified antibody (physicochemical characterization, immunological properties, biological activities, contaminants, ...)

- Determination of the virus clearance studies

Before clinical trials

- Product safety testing: Sterility (bacteria and fungi), in vitro and in vivo testing for adventitious viruses, murine retrovirus testing..., product safety data needed before the initiation of feasibility trials in serious or immediately life-threatening conditions, it serves to evaluate dangerous potential of the product.

- Feasibility testing: These are pilot studies whose objectives include, among others, early characterization of safety and initial proof of concept in a small specific patient population (in vitro or in vivo testing).

Preclinical studies

- Testing cross-reactivity of antibody: to highlight unwanted interactions (toxicity) of antibodies with previously characterized tissues. This study can be performed in vitro (reactivity of the antibody or immunoconjugate should be determined with a quick-frozen adult tissues) or in vivo (with appropriates animal models).

- Preclinical pharmacology and toxicity testing: preclinical safety testing of antibody is designed to identify possible toxicity in humans, to estimate the likelihood and severity of potential adverse events in humans, and to identify a safe starting dose and dose escalation, when possible.

- Animal toxicity studies: Acute toxicity testing, repeat-dose toxicity testing, long-term toxicity testing

- Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics testing: Use for determinate clinical dosages, antibody activities, evaluation of the potential clinical effects

Structure prediction and computational antibody design

The importance of antibodies in health care and the biotechnology industry demands knowledge of their structures at high resolution. This information is used for protein engineering, modifying the antigen binding affinity, and identifying an epitope, of a given antibody. X-ray crystallography is one commonly used method for determining antibody structures. However, crystallizing an antibody is often laborious and time-consuming. Computational approaches provide a cheaper and faster alternative to crystallography, but their results are more equivocal, since they do not produce empirical structures. Online web servers such as Web Antibody Modeling (WAM) and Prediction of Immunoglobulin Structure (PIGS) enables computational modeling of antibody variable regions. Rosetta Antibody is a novel antibody FV region structure prediction server, which incorporates sophisticated techniques to minimize CDR loops and optimize the relative orientation of the light and heavy chains, as well as homology models that predict successful docking of antibodies with their unique antigen.

The ability to describe the antibody through binding affinity to the antigen is supplemented by information on antibody structure and amino acid sequences for the purpose of patent claims. Several methods have been presented for computational design of antibodies based on the structural bioinformatics studies of antibody CDRs.

There are a variety of methods used to sequence an antibody including Edman degradation, cDNA, etc.; albeit one of the most common modern uses for peptide/protein identification is liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). High volume antibody sequencing methods require computational approaches for the data analysis, including de novo sequencing directly from tandem mass spectra and database search methods that use existing protein sequence databases. Many versions of shotgun protein sequencing are able to increase the coverage by utilizing CID/HCD/ETD fragmentation methods and other techniques, and they have achieved substantial progress in attempt to fully sequence proteins, especially antibodies. Other methods have assumed the existence of similar proteins, a known genome sequence, or combined top-down and bottom up approaches. Current technologies have the ability to assemble protein sequences with high accuracy by integrating de novo sequencing peptides, intensity, and positional confidence scores from database and homology searches.

Antibody mimetic

Antibody mimetics are organic compounds, like antibodies, that can specifically bind antigens. They consist of artificial peptides or proteins, or aptamer-based nucleic acid molecules with a molar mass of about 3 to 20 kDa. Antibody fragments, such as Fab and nanobodies are not considered as antibody mimetics. Common advantages over antibodies are better solubility, tissue penetration, stability towards heat and enzymes, and comparatively low production costs. Antibody mimetics have being developed and commercialized as research, diagnostic and therapeutic agents.

Optimer ligands

Optimer ligands are a novel class of antibody mimetics. These nucleic acid based affinity ligands are developed in vitro to generate specific and sensitive affinity ligands that are being applied across therapeutics, drug delivery, bioprocessing, diagnostics, and basic research.