From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tariffs have historically served a key role in the trade policy of the United States. Their purpose was to generate revenue for the federal government and to allow for import substitution industrialization (industrialization of a nation by replacing foreign imports with domestic production) by acting as a protective barrier around infant industries. They also aimed to reduce the trade deficit and the pressure of foreign competition. Tariffs were one of the pillars of the American System

that allowed the rapid development and industrialization of the United

States. The United States pursued a protectionist policy from the

beginning of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century.

Between 1861 and 1933, they had one of the highest average tariff rates

on manufactured imports in the world. However American agricultural and

industrial were cheaper than rival products and the tariff had an impact

primarily on wool products. After 1942 the U.S. promoted worldwide free

trade.

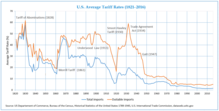

According to Dartmouth economist Douglas Irwin, tariffs have

serve three primary purposes: "to raise revenue for the government, to

restrict imports and protect domestic producers from foreign

competition, and to reach reciprocity agreements that reduce trade

barriers." From 1790 to 1860, average tariffs increased from 20 percent to 60 percent before declining again to 20 percent.

From 1861 to 1933, which Irwin characterizes as the "restriction

period", the average tariffs increased to 50 percent and remained at

that level for several decades. From 1934 onwards, which Irwin

characterizes as the "reciprocity period", the average tariff declined

substantially until it leveled off at 5 percent.

Tariff revenues

Tariffs were the greatest (approaching 95% at times) source of federal revenue until the federal income tax

began after 1913. For well over a century the federal government was

largely financed by tariffs averaging about 20% on foreign imports. At

the end of the American Civil War

in 1865 about 63% of Federal income was generated by the excise taxes,

which exceeded the 25.4% generated by tariffs. In 1915 during World War I

tariffs generated only 30.1% of revenues. Since 1935 tariff income has

continued to be a declining percentage of Federal tax income.

Historical trends

Average tariff rates (France, UK, US)

Average Tariff Rates in US (1821–2016)

U.S. Trade Balance and Trade Policy (1895–2015)

Average Tariff Rates for Selected Countries (1913–2007)

Average Tariff Rates on manufactured products

Average Levels of Duties (1875 and 1913)

After the United States achieved independence in 1783, under the Articles of Confederation,

the U.S. federal government, could not collect taxes directly but had

to "request" money from each state—an almost fatal flaw for a federal

government. Lack of ability to tax directly was one of several major

flaws in the Articles of Confederation. The ability to tax directly was

addressed in the drafting of the United States Constitution in May to September 1787 Constitutional Convention (United States) in Philadelphia. It came into effect in 1789. It specified that the United States House of Representatives

has to originate all tax and tariff laws. The new government needed a

way to collect taxes from all the states that were easy to enforce and

had only a nominal cost to the average citizen. They had just finished a

war on "Taxation without Representation". The Tariff of 1789

was the second bill signed by President George Washington imposing a

tariff of about 5% on nearly all imports, with a few exceptions. In 1790

the United States Revenue Cutter Service was established to primarily enforce and collect the import tariffs. This service later became the United States Coast Guard.

Many American intellectuals and politicians during the country's

catching-up period felt that the free trade theory advocated by British

classical economists was not suited to their country. They argued that

the country should develop manufacturing industries and use government

protection and subsidies for this purpose, as Britain had done before

them. Many of the great American economists of the time, until the last

quarter of the 19th century, were strong advocates of industrial

protection: Daniel Raymond who influenced Friedrich List, Mathew Carey and his son Henry, who was one of Lincoln's economic advisers. The intellectual leader of this movement was Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States (1789-1795). Thus, it was against David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage

that the United States protected its industry. They pursued a

protectionist policy from the beginning of the 19th century until the

middle of the 20th century, after the Second World War.

In Report on Manufactures

which is considered the first text to express modern protectionist

theory, Alexander Hamilton argued that if a country wished to develop a

new activity on its soil, it would have to temporarily protect it.

According to him, this protection against foreign producers could take

the form of import duties or, in rare cases, prohibition of imports. He

called for customs barriers to allow American industrial development and

to help protect infant industries, including bounties (subsidies)

derived in part from those tariffs. He also believed that duties on raw

materials should be generally low.

Hamilton argued that despite an initial "increase of price" caused by

regulations that control foreign competition, once a "domestic

manufacture has attained to perfection… it invariably becomes cheaper".

Alexander Hamilton and Daniel Raymond were among the first theorists to present the infant industry argument.

Hamilton was the first to use the term "infant industries" and to

introduce it to the forefront of economic thinking. He believed that

political independence was predicated upon economic independence.

Increasing the domestic supply of manufactured goods, particularly war

materials, was seen as an issue of national security. And he feared that

Britain's policy towards the colonies would condemn the United States

to be only producers of agricultural products and raw materials.

Britain initially did not want to industrialize the American

colonies, and implemented policies to that effect (for example, banning

high value-added manufacturing activities). Under British rule, America

was denied the use of tariffs to protect its new industries. Thus, the

American Revolution was, to some extent, a war against this policy, in

which the commercial elite of the colonies rebelled against being forced

to play a lesser role in the emerging Atlantic economy. This explains

why, after independence, the Tariff Act of 1789 was the second bill of

the Republic signed by President Washington allowing Congress to impose a

fixed tariff of 5% on all imports, with a few exceptions

The Congress passed a tariff act (1789), imposing a 5% flat rate tariff on all imports.

Between 1792 and the war with Britain in 1812, the average tariff level

remained around 12.5%. In 1812 all tariffs were doubled to an average

of 25% in order to cope with the increase in public expenditure due to

the war. A significant shift in policy occurred in 1816, when a new law

was introduced to keep the tariff level close to the wartime

level—especially protected were cotton, woolen, and iron goods.

The American industrial interests that had blossomed because of the

tariff lobbied to keep it, and had it raised to 35 percent in 1816. The

public approved, and by 1820, America's average tariff was up to 40

percent.

In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name "American System

which consisted of protecting industries and developing infrastructure

in explicit opposition to the "British system" of free trade.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) was partially fought over the

issue of tariffs. The agrarian interests of the South were opposed to

any protection, while the manufacturing interests of the North wanted to

maintain it. The fledgling Republican Party led by Abraham Lincoln,

who called himself a "Henry Clay tariff Whig", strongly opposed free

trade. Early in his political career, Lincoln was a member of the

protectionist Whig Party and a supporter of Henry Clay. In 1847, he

declared: "Give us a protective tariff, and we shall have the greatest nation on earth". He implemented a 44-percent tariff during the Civil War—in part to pay for railroad subsidies and for the war effort, and to protect favored industries.

Tariffs remained at this level even after the war, thus the victory of

the North in the Civil War ensured that the United States remained one

of the greatest practitioners of tariff protection for industry.

From 1871 to 1913, "the average U.S. tariff on dutiable imports

never fell below 38 percent [and] gross national product (GNP) grew 4.3

percent annually, twice the pace in free trade Britain and well above

the U.S. average in the 20th century," notes Alfred Eckes Jr, chairman of the U.S. International Trade Commission under President Reagan.

In 1896, the GOP pledged platform pledged to "renew and emphasize

our allegiance to the policy of protection, as the bulwark of American

industrial independence, and the foundation of development and

prosperity. This true American policy taxes foreign products and

encourages home industry. It puts the burden of revenue on foreign

goods; it secures the American market for the American producer. It

upholds the American standard of wages for the American workingman".

In 1913, following the electoral victory of the Democrats in

1912, there was a significant reduction in the average tariff on

manufactured goods from 44% to 25%. However, the First World War

rendered this bill ineffective, and new "emergency" tariff legislation

was introduced in 1922, after the Republicans returned to power in 1921.

According to Ha-Joon Chang,

the United States, while being protectionist, was the fastest growing

economy in the world throughout the 19th century and into the 1920s.

It was only after the Second World War that the U.S. liberalized its

trade (although not as unequivocally as Britain did in the

mid-nineteenth century).

Colonial Era to 1789

In

the colonial era, before 1775, nearly every colony levied its own

tariffs, usually with lower rates for British products. There were taxes

on ships (on a tonnage basis), import taxes on slaves, export taxes on

tobacco, and import taxes on alcoholic beverages. The London government insisted on a policy of mercantilism whereby only British ships could trade in the colonies. In defiance, some American merchants engaged in smuggling.

During the Revolution, the British blockade from 1775 to 1783 largely ended foreign trade. In the 1783–89 Confederation Period,

each state set up its own trade rules, often imposing tariffs or

restrictions on neighboring states. The new Constitution, which went

into effect in 1789, banned interstate tariffs or trade restrictions, as

well as state taxes on exports.

Early National period, 1789–1828

The framers of the United States Constitution gave the federal government authority to tax, stating that Congress has the power to "... lay

and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, pay the debts and

provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United

States." and also "To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among

the several States, and with the Indian Tribes." Tariffs between states

is prohibited by the U.S. Constitution, and all domestically made

products can be imported or shipped to another state tax-free.

Responding to an urgent need for revenue and a trade imbalance

with England that was fast destroying the infant American industries and

draining the nation of its currency, the First United States Congress passed, and President George Washington signed, the Hamilton Tariff of 1789, which authorized the collection of duties on imported goods. Customs

duties as set by tariff rates up to 1860 were usually about 80–95% of

all federal revenue. Having just fought a war over taxation (among other

things) the U.S. Congress wanted a reliable source of income that was

relatively unobtrusive and easy to collect. It also sought to protect

the infant industries that had developed during the war but which were

now threatened by cheaper imports, especially from England. Tariffs and

excise taxes were authorized by the United States Constitution and

recommended by the first United States Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton

in 1789 to tax foreign imports and set up low excise taxes on whiskey

and a few other products to provide the Federal Government with enough

money to pay its operating expenses and to redeem at full value U.S.

Federal debts and the debts the states had accumulated during the

Revolutionary War. The Congress set low excise taxes on only a few

goods, such as, whiskey, rum, tobacco, snuff and refined sugar. The tax on whiskey was highly controversial and set off massive protests by Western Farmers in the Whiskey Rebellion

of 1794, which was suppressed by General Washington at the head of an

army. The whiskey excise tax collected so little and was so despised it

was abolished by President Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

All tariffs were on a long list of goods (dutiable goods) with

different customs rates and some goods on a "free" list. Books and

publications were nearly always on the free list. Congress spent

enormous amounts of time figuring out these tariff import tax schedules.

With tariffs providing the basic federal revenue, an embargo on

trade, or an enemy blockade, would threaten havoc. This happened in

connection with the American economic warfare against Britain in the

1807–15 period. In 1807 imports dropped by more than half and some

products became much more expensive or unobtainable. Congress passed the

Embargo Act of 1807 and the Non-Intercourse Act (1809)

to punish British and French governments for their actions;

unfortunately their main effect was to reduce imports even more. The War of 1812

brought a similar set of problems as U.S. trade was again restricted by

British naval blockades. The fiscal crisis was made much worse by the

abolition of the First Bank of the U.S., which was the national bank. It was reestablished right after the war.

The lack of imported goods relatively quickly gave very strong

incentives to start building several U.S. industries in the Northeast.

Textiles and machinery manufacturing plants especially grew. Many new

industries were set up and run profitably during the wars and about half

of them failed after hostilities ceased and normal import competition

resumed. Industry in the U.S. was advancing up the skill set, innovation

knowledge and organization curve as they adapted to the Industrial

Revolution's new machines and techniques.

The Tariff Act of 1789 imposed the first national source of revenue for the newly formed United States. The new U.S. Constitution

ratified in 1789, allowed only the federal government to levy uniform

tariffs. Only the federal government could set tariff rates (customs),

so the old system of separate state rates disappeared. The new law taxed

all imports at rates from 5 to 15 percent. These rates were primarily

designed to generate revenue to pay the annual expenses of the federal

government and the national debt and the debts the states had

accumulated during the American War of Independence

and to also promote manufactures and independence from foreign nations,

especially for defense needs. Hamilton believed that all Revolutionary

War debt should be paid in full to establish and keep U.S. financial

credibility. In addition to income in his Report on Manufactures

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton proposed a far-reaching plan to

use protective tariffs as a lever for rapid industrialization. In the

late 18th century the industrial age was just starting and the United

States had little or no textile industry—the heart of the early

Industrial Revolution. The British government having just lost the Revolutionary War

tried to maintain their near monopoly on cheap and efficient textile

manufacturing by prohibiting the export of textile machines, machine

models or the emigration of people familiar with these machines.

Clothing in the early United States was nearly all hand made by a very

time consuming and expensive process—just like it had been made for

centuries before. The new textile manufacturing techniques in Britain

were often over thirty times cheaper as well as being easier to use,

more efficient and productive. Hamilton believed that a stiff tariff on

imports would not only raise income but "protect" and help subsidize

early efforts at setting up manufacturing facilities that could compete

with British products.

Samuel Slater

in 1789 emigrated (illegally since he was familiar with textile

manufacturing) from Britain. Looking for opportunities he heard of the

failing attempts at making cotton mills in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Contacting the owners he promised to see if he could fix their

mills—they offered him a full partnership if he succeeded. Declaring

their early attempts unworkable he proceeded from January 1790 to

December 1790 to build the first operational textile manufacturing

facility in the United States. The Industrial Revolution

was off and running in the United States. Initially the cost of their

textiles was slightly higher than the cost of equivalent British goods

but the tariff helped protect their early start-up industry.

Ashley notes that:

- From 1790 onwards there were constant alterations in the tariff

between 1792 and 1816 there were some twenty-five Tariff Acts passed,

all modifying the customs duties in one way or another. But Hamilton's

Report, and the ideas it embodied, do not seem to have exercised any

special influence on the legislation of this period; the motives were

always financial.

Higher tariffs were adopted during and after the War of 1812, when nationalists such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun

saw the need for more federal income and more industry. In wartime,

they declared, having a home industry was a necessity to avoid

shortages. Likewise owners of the small new factories that were

springing up in the northeast to mass-produce boots, hats, nails and

other common items wanted higher tariffs that would significantly

protect them when the more efficient British producers returned after

the war ended. A 10% discount on the customs tax was offered on items

imported in American ships, so that the American merchant marine would

be supported.

Once industrialization and mass production started, the demand

for higher and higher tariffs came from manufacturers and factory

workers. They believed that their businesses should be protected from

the lower wages and more efficient factories of Britain and the rest of

Europe. Nearly every northern Congressman was eager to logroll a higher

tariff rate for his local industry. Senator Daniel Webster,

formerly a spokesperson for Boston's merchants who imported goods (and

wanted low tariffs), switched dramatically to represent the

manufacturing interests in the Tariff of 1824.

Rates were especially high for bolts of cloth and for bar iron, of

which Britain was a low-cost producer. The culmination came in the Tariff of 1828, ridiculed by free traders as the "Tariff of Abominations",

with import custom duties averaging over 25 percent. Intense political

opposition to higher tariffs came from Southern Democrats and plantation

owners in South Carolina who had little manufacturing industry and

imported some products with high tariffs. They would have to pay more

for imports. They claimed their economic interest was being unfairly

injured. They attempted to "nullify" the federal tariff and spoke of

secession from the Union (see the Nullification Crisis). President Andrew Jackson

let it be known he would use the U.S. Army to enforce the law, and no

state supported the South Carolina call for nullification. A compromise

ended the crisis included a lowering of the average tariff rate over ten

years to a rate of 15% to 20%.

Second Party System, 1829–1859

The Democrats dominated the Second Party System

and set low tariffs designed to pay for the government but not protect

industry. Their opponents the Whigs wanted high protective tariffs but

usually were outvoted in Congress. Tariffs soon became a major political

issue as the Whigs (1832–1852) and (after 1854) the Republicans wanted to protect their mostly northern industries and constituents by voting for higher tariffs and the Southern Democrats,

which had very little industry but imported many goods voted for lower

tariffs. Each party as it came into power voted to raise or lower

tariffs under the constraints that the Federal Government always needed a

certain level of revenues. The United States public debt was paid off in 1834 and President Andrew Jackson,

a strong Southern Democrat, oversaw the cutting of the tariff rates

roughly in half and eliminating nearly all federal excise taxes in about

1835.

Henry Clay and his Whig Party,

envisioning a rapid modernization based on highly productive factories,

sought a high tariff. Their key argument was that startup factories, or

"infant industries", would at first be less efficient than European

(British) producers. Furthermore, American factory workers were paid

higher wages than their European competitors. The arguments proved

highly persuasive in industrial districts. Clay's position was adopted

in the 1828 and 1832 Tariff Acts. The Nullification Crisis

forced a partial abandonment of the Whig position. When the Whigs won

victories in the 1840 and 1842 elections, taking control of Congress,

they re-instituted higher tariffs with the Tariff of 1842.

In examining these debates Moore finds that they were not precursors to

Civil War. Instead they looked backward and continued the old debate

whether foreign trade policy should embrace free trade or protectionism.

Walker Tariff

The Democrats won in 1845, electing James K. Polk as president. Polk succeeded in passing the Walker tariff

of 1846 by uniting the rural and agricultural factions of the entire

country for lower tariffs. They sought a level of a "tariff for revenue

only" that would pay the cost of government but not show favoritism to

one section or economic sector at the expense of another. The Walker

Tariff actually increased trade with Britain and others and brought in

more revenue to the federal treasury than the higher tariff. The average

tariff on the Walker Tariff was about 25%. While protectionists in

Pennsylvania and neighboring states were angered, the South achieved its

goal of setting low tariff rates before the Civil War.

Low tariff of 1857

The Walker Tariff remained in place until 1857, when a nonpartisan coalition lowered them again with the Tariff of 1857 to 18%. This was in response to the British repeal of their protectionist "Corn Laws".

The Democrats in Congress, dominated by Southern Democrats, wrote

and passed the tariff laws in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, and kept

reducing rates, so that the 1857 rates were down to about 15%, a move

that boosted trade so overwhelmingly that revenues actually increased,

from just over $20 million in 1840 ($0.5 billion in 2020 dollars), to

more than $80 million by 1856 ($1.8 billion).

The South had almost no complaints but the low rates angered many

Northern industrialists and factory workers, especially in Pennsylvania,

who demanded protection for their growing iron industry. The Republican Party

replaced the Whigs in 1854 and also favored high tariffs to stimulate

industrial growth; it was part of the 1860 Republican platform.

Third Party System

After the Second Party System ended in 1854 the Democrats lost

control and the new Republican Party had its opportunity to raise rates.

The Morrill Tariff

significantly raising tariff rates became possible only after the

Southern Senators walked out of Congress when their states left the

Union, leaving a Republican majority. It was signed by Democratic

President James Buchanan in early March 1861 shortly before President Abraham Lincoln

took office. Pennsylvania iron mills and New England woolen mills

mobilized businessmen and workers to call for high tariffs, but

Republican merchants wanted low tariffs. The high tariff advocates lost

in 1857, but stepped up their campaign by blaming the economic recession

of 1857 on the lower rates. Economist Henry Charles Carey of Philadelphia was the most outspoken advocate, along with Horace Greeley and his influential newspaper, the New York Tribune. Increases were finally enacted in February 1861 after Southerners resigned their seats in Congress on the eve of the Civil War.

Some historians in recent decades have minimized the tariff issue

as a cause of the war, noting that few people in 1860–61 said it was of

central importance to them. Compromises were proposed in 1860–61 to

save the Union, but they did not involve the tariff.

Arguably, the effects of a tariff enacted in March 1861 could have made

little effect upon any delegation which met prior to its signing. It is

indicative of the Northern industrial supported and anti-agrarian

position of the 1861 Republican-controlled congress. Some secessionist

documents do mention a tariff issue, though not nearly as often as the

preservation of the institution of slavery. However, a few libertarian economists place more importance on the tariff issue. The arguments that tariffs were a major cause of the Civil War have become a staple of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy.

1860–1912

Civil War

During the war far more revenue was needed, so the rates were raised

again and again, along with many other taxes such as excise taxes on

luxuries and income taxes on the rich.

By far most of the wartime government revenue came from bonds and loans

($2.6 billion), not taxes ($357 million) or tariffs ($305 million).

The Morrill Tariff took effect a few weeks before the war began on April 12, 1861, and was not collected in the South. The Confederate States of America

(CSA) passed its own tariff of about 15% on most items, including many

items that previously were duty-free from the North. Previously tariffs

between states were prohibited. The Confederates believed that they

could finance their government by tariffs. The anticipated tariff

revenue never appeared as the Union Navy blockaded their ports and the

Union army restricted their trade with the Northern states. The

Confederacy collected a mere $3.5 million in tariff revenue from the

Civil War start to end and had to resort to inflation and confiscation

instead for revenue.

Reconstruction era

Historian Howard K. Beale

argued that high tariffs were needed during the Civil War, but were

retained after the war for the benefit of Northern industrialists, who

would otherwise lose markets and profits. To keep political control of

Congress, Beale argued, Northern Industrialists worked through the

Republican Party and supported Reconstruction

policies that kept low-tariff Southern whites out of power. The Beale

thesis was widely disseminated by the influential survey of Charles A. Beard, The Rise of American Civilization (1927).

In the late 1950s historians rejected the Beale–Beard thesis by

showing that Northern businessmen were evenly divided on the tariff, and

were not using Reconstruction policies to support it.

Politics of protection

The

iron and steel industry, and the wool industry, were the well-organized

interests groups that demanded (and usually obtained) high tariffs

through support of the Republican Party. Industrial workers had much

higher wages than their European counterparts, and they credited it to

the tariff and voted Republican.

Democrats were divided on the issue, in large part because of

pro-tariff elements in the Pennsylvania party who wanted to protect the

growing iron industry, as well as pockets of high tariff support in

nearby industrializing states. However President Grover Cleveland

made low tariffs the centerpiece of Democratic Party policies in the

late 1880s. His argument is that high tariffs were an unnecessary and

unfair tax on consumers. The South and West generally supported low

tariffs, and the industrial East high tariffs. Republican William McKinley was the outstanding spokesman for high tariffs, promising it would bring prosperity for all groups.

After the Civil War, high tariffs remained as the Republican

Party remained in office and the Southern Democrats were restricted from

office. Advocates insisted that tariffs brought prosperity to the

nation as a whole and no one was really injured. As industrialization

proceeded apace throughout the Northeast, some Democrats, especially

Pennsylvanians, became high tariff advocates.

Farmers and wool

The

Republican high-tariff advocates appealed to farmers with the theme

that high-wage factory workers would pay premium prices for foodstuffs.

This was the "home market" idea, and it won over most farmers in the

Northeast, but it had little relevance to the southern and western

farmers who exported most of their cotton, tobacco and wheat. In the

late 1860s the wool manufacturers (based near Boston and Philadelphia)

formed the first national lobby, and cut deals with wool-growing farmers

in several states. Their challenge was that fastidious wool producers

in Britain and Australia marketed a higher quality fleece than the

Americans, and that British manufacturers had costs as low as the

American mills. The result was a wool tariff that helped the farmers by a

high tariff rate on imported wool—a tariff the American manufacturers

had to pay—together with a high tariff on finished woolens and worsted

goods.

U.S. industrial output

Apart

from wool and woolens, American industry and agriculture—and industrial

workers—had become the most efficient in the world in most industries

by the 1880s as they took the lead in the Industrial Revolution.

No other country had the industrial capacity, large market, high

efficiency and low costs, or the complex distribution system needed to

compete in most markets in the vast American market. Most imports were a

few "luxury" goods. Indeed, it was the British who watched cheaper

American products flooded their home islands. The London Daily Mail in 1900 complained:

We have lost to the American manufacturer electrical

machinery, locomotives, steel rails, sugar-producing and agricultural

machinery, and latterly even stationary engines, the pride and backbone

of the British engineering industry.

Nevertheless, some American manufacturers and union workers demanded

the high tariff be maintained. The tariff represented a complex balance

of forces. Railroads, for example, consumed vast quantities of steel. To

the extent tariffs raised steel prices, they paid much more making

possible the U.S steel industry's massive investment to expand capacity

and switch to the Bessemer process and later to the open hearth furnace.

Between 1867 and 1900 U.S. steel production increased more than 500

times from 22,000 tons to 11,400,000 tons and Bessemer steel rails,

first made in the U.S that would last 18 years under heavy traffic,

would come to replace the old wrought iron rail that could only endure

two years under light service.

Taussig says that in 1881, British steel rails sold for $31 a ton, and

if Americans imported them they paid a $28/ton tariff, giving $59/ton

for an imported ton of rails. American mills charged $61/ton and made a

good profit, which was then reinvested into increased capacity, higher

quality steels, higher wages and benefits and more efficient production.

By 1897 the American steel rail price had dropped to $19.60 per ton

compared to the British price at $21.00—not including the $7.84 duty

charge—demonstrating that the tariff had performed its purpose of giving

the industry time to become competitive.

Then the U.S. steel industry became an exporter of steel rail to

England selling below the British price and during WW I would become the

largest supplier of steel to the allies. From 1915 through 1918, the

largest American steel company, U.S. Steel, alone delivered more steel

each year than Germany and Austria-Hungary combined, totaling 99,700,000

tons during WW I.

The Republicans became masters of negotiating exceedingly complex

arrangements so that inside each of their congressional districts there

were more satisfied "winners" than disgruntled "losers". The tariff

after 1880 was an ideological relic with no longer any economic

rationale.

Cleveland tariff policy

Democratic President Grover Cleveland

redefined the issue in 1887, with his stunning attack on the tariff as

inherently corrupt, opposed to true republicanism, and inefficient to

boot: "When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees

to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry

and enterprise... it is plain that the exaction of more than [minimal

taxes] is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American

fairness and justice." The election of 1888 was fought primarily over the tariff issue, and Cleveland lost. Republican Congressman William McKinley argued,

Free foreign trade gives our money, our manufactures, and

our markets to other nations to the injury of our labor, our

tradespeople, and our farmers. Protection keeps money, markets, and

manufactures at home for the benefit of our own people.

Democrats campaigned energetically against the high McKinley tariff

of 1890, and scored sweeping gains that year; they restored Cleveland to

the White House in 1892. The severe depression that started in 1893

ripped apart the Democratic party. Cleveland and the pro-business Bourbon Democrats

insisted on a much lower tariff. His problem was that Democratic

electoral successes had brought in Democratic congressmen from

industrial districts who were willing to raise rates to benefit their

constituents. The Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act

of 1894 did lower overall rates from 50 percent to 42 percent, but

contained so many concessions to protectionism that Cleveland refused to

sign it (it became law anyway).

McKinley tariff policy

President Teddy Roosevelt watches GOP team pull apart on tariff issue

McKinley campaigned heavily in 1896

on the high tariff as a positive solution to depression. Promising

protection and prosperity to every economic sector, he won a smashing

victory. The Republicans rushed through the Dingley tariff

in 1897, boosting rates back to the 50 percent level. Democrats

responded that the high rates created government sponsored "trusts"

(monopolies) and led to higher consumer prices. McKinley won reelection

by an even bigger landslide and started talking about a post-tariff era

of reciprocal trade agreements. Reciprocity went nowhere; McKinley's

vision was a half century too early. The Republicans split bitterly on the Payne–Aldrich Tariff of 1909. Republican President Theodore Roosevelt

(1901–1909) saw the tariff issue was ripping his party apart, so he

postponed any consideration of it. The delicate balance flew apart on

under Republican William Howard Taft.

He campaigned for president in 1908 for tariff "reform", which everyone

assumed meant lower rates. The House lowered rates with the Payne Bill,

then sent it to the Senate where Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich

mobilized high-rate Senators. Aldrich was a New England businessman and

a master of the complexities of the tariff, the Midwestern Republican

insurgents were rhetoricians and lawyers who distrusted the special

interests and assumed the tariff was "sheer robbery" at the expense of

the ordinary consumer. Rural America believed that its superior morality

deserved special protection, while the dastardly immorality of the

trusts—and cities generally—merited financial punishment. Aldrich baited

them. Did the insurgents want lower tariffs? His wickedly clever Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 lowered the protection on Midwestern farm products, while raising rates favorable to his Northeast.

By 1913 with the new income tax generating revenue, the Democrats in Congress were able to reduce rates with the Underwood Tariff.

The outbreak of war in 1914 made the impact of tariffs of much less

importance compared to war contracts. When the Republicans returned to

power they returned the rates to a high level in the Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922. The next raise came with the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 at the start of the Great Depression.

Tariff with Canada

The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty increased trade between 1855 and its ending in 1866. When it ended Canada turned to tariffs. The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party

in 1879 after it returned to power. It had been an official policy,

however, since 1876. It was based on high tariffs to protect Canada's

manufacturing industry. Macdonald campaigned on the policy in the 1878 election, and handily beat the Liberal Party, which supported free trade.

Efforts to restore free trade with Canada collapsed when Canada rejected a proposed reciprocity treaty in fear of American imperialism in the 1911 federal election.

Taft negotiated a reciprocity agreement with Canada, that had the

effect of sharply lowering tariffs. Democrats supported the plan but

Midwestern Republicans bitterly opposed it. Barnstorming the country for

his agreement, Taft undiplomatically pointed to the inevitable

integration of the North American economy, and suggested that Canada

should come to a "parting of the ways" with Britain. Canada's

Conservative Party, under the leadership of Robert Borden,

now had an issue to regain power from the low-tariff Liberals; after a

surge of pro-imperial anti-Americanism, the Conservatives won. Ottawa

rejected reciprocity, reasserted the National Policy and went to London

first for new financial and trade deals. The Payne Aldrich Tariff of

1909 actually changed little and had slight economic impact one way or

the other, but the political impact was enormous. The insurgents felt

tricked and defeated and swore vengeance against Wall Street and its

minions Taft and Aldrich. The insurgency led to a fatal split down the

middle in 1912 as the GOP lost its balance wheel.

1913 to present

Starting in the Civil War, protection was the ideological cement holding the Republican coalition together.

High tariffs were used to promise higher sales to business, higher

wages to industrial workers, and higher demand for their crops to

farmers. Democrats said it was a tax on the little man. After 1900

Progressive insurgents said it promoted monopoly. It had greatest

support in the Northeast, and greatest opposition in the South and West.

The Midwest was the battle ground.

The tariff issue was pulling the GOP apart. Roosevelt tried to

postpone the issue, but Taft had to meet it head on in 1909 with the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act. Eastern conservatives led by Nelson W. Aldrich

wanted high tariffs on manufactured goods (especially woolens), while

Midwesterners called for low tariffs. Aldrich outmaneuvered them by

lowering the tariff on farm products, which outraged the farmers. The

great battle over the high Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act in 1910 ripped the Republicans apart and set up the realignment in favor of the Democrats.

Woodrow Wilson made a drastic lowering of tariff rates a major priority for his presidency. The 1913 Underwood Tariff

cut rates, but the coming of World War I in 1914 radically revised

trade patterns. Reduced trade and, especially, the new revenues

generated by the federal income tax

made tariffs much less important in terms of economic impact and

political rhetoric. The Wilson administration desired a 'revamping' of

the current banking system, "... so that the banks may be the instruments, not the masters, of business and of individual enterprise and initiative.". President Wilson achieved this in the Federal Reserve Act

of 1913. Working with the bullish Senator Aldrich and former

presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, he perfected a way to

centralize the banking system to allow Congress to closely allocate

paper money production.

The Federal Reserve Act, with the Sixteenth Amendment of the

Constitution, would create a trend of new forms of government funding.

Ihe Democrats lowered the tariff in 1913 but the economic dislocations

of the First World War made it irrelevant. When the Republicans returned

to power in 1921 they again imposed a protective tariff. They raised it again with the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 to meet the Great Depression in the United States.

But that made the depression worse. This time it backfired, as Canada,

Britain, Germany, France and other industrial countries retaliated with

their own tariffs and special, bilateral trade deals. American imports

and exports both went into a tailspin.

The Democrats promised an end to protection on a reciprocal

country-by-country basis (which they did), hoping this would expand

foreign trade (which it did not). By 1936 the tariff issue had faded

from politics, and the revenue it raised was small. In World War II,

both tariffs and reciprocity were insignificant compared to trade

channeled through Lend-Lease. Low rates dominated the debate for the rest of the 20th century. In 2017 Donald Trump promised to use protective tariffs as a weapon to restore greatness to the economy.

Tariffs and the Great Depression

The

years 1920 to 1929 are generally misdescribed as years in which

protectionism increased in Europe. In fact, from a general point of

view, the crisis was preceded in Europe by trade liberalisation. The

weighted average of tariffs remained tendentially the same as in the

years preceding the First World War: 24.6% in 1913, as against 24.9% in

1927. In 1928 and 1929, tariffs were lowered in almost all developed

countries.

In addition, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was signed by Hoover on June

17, 1930, while the Wall Street crash took place in the fall of 1929.

Most of the trade contraction occurred between January 1930 and July

1932, before most protectionist measures were introduced (except for the

limited measures applied by the United States in the summer of 1930).

In the view of Maurice Allais, it was therefore the collapse of international liquidity that caused the contraction of trade, not customs tariffs.

Milton Friedman

also held the opinion that the Smoot–Hawley tariff of 1930 did not

cause the Great Depression. Douglas A. Irwin writes : "most economists,

both liberal and conservative, doubt that Smoot Hawley played much of a

role in the subsequent contraction."

Peter Temin,

explains a tariff is an expansionary policy, like a devaluation as it

diverts demand from foreign to home producers. He notes that exports

were 7 percent of GNP in 1929, they fell by 1.5 percent of 1929 GNP in

the next two years and the fall was offset by the increase in domestic

demand from tariff. He concludes that contrary the popular argument,

contractionary effect of the tariff was small. (Temin, P. 1989. Lessons from the Great Depression, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass)

William J. Bernstein wrote:

Between

1929 and 1932, real GDP fell 17 percent worldwide, and by 26 percent in

the United States, but most economic historians now believe that only a

minuscule part of that huge loss of both world GDP and the United

States’ GDP can be ascribed to the tariff wars. .. At the time of

Smoot-Hawley's passage, trade volume accounted for only about 9 percent

of world economic output. Had all international trade been eliminated,

and had no domestic use for the previously exported goods been found,

world GDP would have fallen by the same amount — 9 percent. Between 1930

and 1933, worldwide trade volume fell off by one-third to one-half.

Depending on how the falloff is measured, this computes to 3 to 5

percent of world GDP, and these losses were partially made up by more

expensive domestic goods. Thus, the damage done could not possibly have

exceeded 1 or 2 percent of world GDP — nowhere near the 17 percent

falloff seen during the Great Depression... The inescapable conclusion:

contrary to public perception, Smoot-Hawley did not cause, or even

significantly deepen, the Great Depression.

Paul Krugman writes that protectionism does not lead to recessions.

According to him, the decrease in imports (which can be obtained by the

introduction of tariffs) has an expansionary effect, i.e. favourable to

growth. Thus in a trade war, since exports and imports will decrease

equally, for the whole world, the negative effect of a decrease in

exports will be compensated by the expansionary effect of a decrease in

imports. A trade war therefore does not cause a recession. Furthermore,

he notes that the Smoot-Hawley tariff did not cause the Great

Depression. The decline in trade between 1929 and 1933 "was almost

entirely a consequence of the Depression, not a cause. Trade barriers

were a response to the Depression, in part a consequence of deflation."

Trade liberalization

Tariffs up to the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

of 1930, were set by Congress after many months of testimony and

negotiations. In 1934, the U.S. Congress, in a rare delegation of

authority, passed the Reciprocal Tariff Act

of 1934, which authorized the executive branch to negotiate bilateral

tariff reduction agreements with other countries. The prevailing view

then was that trade liberalization may help stimulate economic growth.

However, no one country was willing to liberalize unilaterally. Between

1934 and 1945, the executive branch negotiated over 32 bilateral trade

liberalization agreements with other countries. The belief that low

tariffs led to a more prosperous country are now the predominant belief

with some exceptions. Multilateralism is embodied in the seven tariff

reduction rounds that occurred between 1948 and 1994. In each of these

"rounds", all General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

(GATT) members came together to negotiate mutually agreeable trade

liberalization packages and reciprocal tariff rates. In the Uruguay

round in 1994, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was established to help establish uniform tariff rates.

Currently only about 30% of all import goods are subject to

tariffs in the United States, the rest are on the free list. The

"average" tariffs now charged by the United States are at a historic

low. The list of negotiated tariffs are listed on the Harmonized Tariff Schedule as put out by the United States International Trade Commission.

Post World War II

After the war the U.S. promoted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

(GATT) established in 1947, to minimize tariffs and other restrictions,

and to liberalize trade among all capitalist countries. In 1995 GATT

became the World Trade Organization (WTO); with the collapse of Communism its open markets/low tariff ideology became dominant worldwide in the 1990s.

American industry and labor prospered after World War II, but

hard times set in after 1970. For the first time there was stiff

competition from low-cost producers around the globe. Many rust belt

industries faded or collapsed, especially the manufacture of steel, TV

sets, shoes, toys, textiles and clothing. Toyota and Nissan

threatened the giant domestic auto industry. In the late 1970s Detroit

and the auto workers union combined to fight for protection. They

obtained not high tariffs, but a voluntary restriction of imports from

the Japanese government. Quotas were two-country diplomatic agreements

that had the same protective effect as high tariffs, but did not invite

retaliation from third countries. By limiting the number of Japanese

automobiles that could be imported, quotas inadvertently helped Japanese

companies push into larger, and more expensive market segments. The

Japanese producers, limited by the number of cars they could export to

America, opted to increase the value of their exports to maintain

revenue growth. This action threatened the American producers'

historical hold on the mid- and large-size car markets.

The Chicken tax was a 1964 response by President Lyndon B. Johnson to tariffs placed by Germany (then West Germany) on importation of US chicken. Beginning in 1962, during the President Kennedy

administration, the US accused Europe of unfairly restricting imports

of American poultry at the request of West German chicken farmers.

Diplomacy failed, and in January 1964, two months after taking office,

President Johnson retaliated by imposing a 25 percent tax on all

imported light trucks. This directly affected the German built Volkswagen vans.

Officially it was explained that the light trucks tax would offset the

dollar amount of imports of Volkswagen vans from West Germany with the

lost American sales of chickens to Europe. But audio tapes from the

Johnson White House reveal that in January 1964, President Johnson was

attempting to convince United Auto Workers's president Walter Reuther,

not to initiate a strike just prior the 1964 election and to support

the president's civil rights platform. Reuther in turn wanted Johnson to

respond to Volkswagen's increased shipments to the United States.

1980s to present

During the Reagan

and George H. W. Bush administrations Republicans abandoned

protectionist policies, and came out against quotas and in favor of the

GATT/WTO policy of minimal economic barriers to global trade. Free trade

with Canada came about as a result of the Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987, which led in 1994 to the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). It was based on Reagan's plan to enlarge the scope of the

market for American firms to include Canada and Mexico. President Bill Clinton, with strong Republican support in 1993, pushed NAFTA through Congress over the vehement objection of labor unions.

Likewise, in 2000 Clinton worked with Republicans to give China entry into WTO and "most favored nation"

trading status (i.e., the same low tariffs promised to any other WTO

member). NAFTA and WTO advocates promoted an optimistic vision of the

future, with prosperity to be based on intellectuals skills and

managerial know-how more than on routine hand labor. They promised that

free trade meant lower prices for consumers. Opposition to liberalized

trade came increasingly from labor unions, who argued that this system

also meant lower wages and fewer jobs for American workers who could not

compete against wages of less than a dollar an hour. The shrinking size

and diminished political clout of these unions repeatedly left them on

the losing side.

Despite overall decreases in international tariffs, some tariffs

have been more resistant to change. For example, due partially to tariff

pressure from the European Common Agricultural Policy, US agricultural subsidies have seen little decrease over the past few decades, even in the face of recent pressure from the WTO during the latest Doha talks.

On March 5, 2002, President George W. Bush placed tariffs on imported steel.

Deindustrialization

According to the Economic Policy Institute,

free trade has created a large trade deficit in the United States for

decades, leading to the closure of many factories and cost the United

States millions of jobs in the manufacturing sector. Trade deficits

replaces well-paying manufacturing jobs with low-wage service jobs.

Moreover, trade deficits lead to significant wage losses, not only for

workers in the manufacturing sector, but also for all workers throughout

the economy who do not have a university degree. For example, in 2011,

100 million full-time, full-year workers without a university degree

suffered an average loss of $1,800 on their annual salary.

Indeed, these workers who have lost their jobs in the

manufacturing sector and who have to accept a reduction in their wages

to find work in other sectors, are creating competition that reduces the

wages of workers already employed in these other sectors. In addition,

the threat of relocation of production facilities leads workers to

accept wage cuts to keep their jobs.

According to the EPI, trade agreements have not reduced trade

deficits but rather increased them. The growing trade deficit with China

comes from China's manipulation of its currency, dumping policies,

subsidies, trade

barriers that give it a very important advantage in international

trade. In addition, industrial jobs lost by imports from China are

significantly better paid than jobs created by exports to China. So even

if imports were equal to exports, workers would still lose out on their

wages.

The manufacturing sector is a sector with very high productivity

growth, which promotes high wages and good benefits for its workers.

Indeed, this sector accounts for more than two thirds of private sector

research and development and employs more than twice as many scientists

and engineers as the rest of the economy. The manufacturing sector

therefore provides a very important stimulus to overall economic growth.

Manufacturing is also associated with well-paid service jobs such as

accounting, business management, research and development and legal

services. Deindustrialisation is therefore also leading to a significant

loss of these service jobs. Deindustrialization thus means the

disappearance of a very important driver of economic growth.

Smuggling and Coast Guard

Historically, high tariffs have led to high rates of smuggling. The United States Revenue Cutter Service

was established by Secretary Hamilton in 1790 as an armed maritime law

and custom enforcement service. Today it remains the primary maritime

law enforcement force in the United States.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is a federal law enforcement agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security

charged with regulating and facilitating international trade,

collecting customs (import duties or tariffs approved by the U.S.

Congress), and enforcing U.S. regulations, including trade, customs and

immigration. They man most border crossing stations and ports. When

shipments of goods arrive at a border crossing or port, customs officers

inspect the contents and charge a tax according to the tariff formula

for that product. Usually the goods cannot continue on their way until

the custom duty is paid. Custom duties are one of the easiest taxes to

collect, and the cost of collection is small.

Tariffs and historical American politicians

In

1896, the GOP platform pledged to "renew and emphasize our allegiance

to the policy of protection, as the bulwark of American industrial

independence, and the foundation of development and prosperity. This

true American policy taxes foreign products and encourages home

industry. It puts the burden of revenue on foreign goods; it secures the

American market for the American producer. It upholds the American

standard of wages for the American workingman."

George Washington

"I use no porter or cheese in my family, but such as is made in America," the inaugural President George Washington

wrote, boasting that these domestic products are "of an excellent

quality." One of the first acts of Congress Washington signed was a

tariff among whose stated purpose was "the encouragement and protection

of manufactures." In his 1790 State of the Union Address, Washington justified his tariff policy for national security reasons:

A free people ought not only to be armed, but

disciplined; to which end a uniform and well-digested plan is requisite;

and their safety and interest require that they should promote such

manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for

essential, particularly military, supplies

Thomas Jefferson

As President Thomas Jefferson

wrote in explaining why his views had evolved to favor more

protectionist policies: "In so complicated a science as political

economy, no one axiom can be laid down as wise and expedient for all

times and circumstances, and for their contraries."

After the War of 1812,

Jefferson's position began to resemble that of Washington, some level

of protection was necessary to secure the nation's political

independence. He said:

experience has taught me that manufactures are now as

necessary to our independence as to our comfort: and if those who quote

me as of a different opinion will keep pace with me in purchasing

nothing foreign where an equivalent of domestic fabric can be obtained,

without regard to difference of price

Henry Clay

In 1832, then the United States Senator from Kentucky,

Henry Clay said about his disdain for "free traders" that "it is not

free trade that they are recommending to our acceptance. It is in

effect, the British colonial system that we are invited to adopt; and,

if their policy prevail, it will lead substantially to the

re-colonization of these States, under the commercial dominion of Great

Britain." Clay said:

When gentlemen have succeeded in their design of an

immediate or gradual destruction of the American System, what is their

substitute? Free trade! Free trade! The call for free trade is as

unavailing as the cry of a spoiled child, in its nurse's arms, for the

moon, or the stars that glitter in the firmament of heaven. It never has

existed; it never will exist. Trade implies, at least two parties. To

be free, it should be fair, equal and reciprocal.

Clay explained that "equal and reciprocal" free trade "never has

existed; [and] it never will exist." He warned against practicing

"romantic trade philanthropy… which invokes us to continue to purchase

the produce of foreign industry, without regard to the state or

prosperity of our own." Clay that he was "utterly and irreconcilably

opposed" to trade which would "throw wide open our ports to foreign

productions" without reciprocation.

James Monroe

In 1822, President James Monroe

observed that "whatever may be the abstract doctrine in favor of

unrestricted commerce," the conditions necessary for its

success—reciprocity and international peace—"has never occurred and can

not be expected." Monroe said, "strong reasons… impose on us the

obligation to cherish and sustain our manufactures."

Abraham Lincoln

President Abraham Lincoln

declared, "Give us a protective tariff and we will have the greatest

nation on earth." Lincoln warned that "the abandonment of the protective

policy by the American Government… must produce want and ruin among our

people."

Lincoln similarly said that, "if a duty amount to full protection

be levied upon an article" that could be produced domestically, "at no

distant day, in consequence of such duty," the domestic article "will be

sold to our people cheaper than before."

Additionally, Lincoln argued that based on economies of scale,

any temporary increase in costs resulting from a tariff would eventually

decrease as the domestic manufacturer produced more.

Lincoln did not see a tariff as a tax on low-income Americans because it

would only burden the consumer according to the amount the consumer

consumed.

By the tariff system, the whole revenue is paid by the consumers of

foreign goods... the burthen of revenue falls almost entirely on the

wealthy and luxurious few, while the substantial and laboring many who

live at home, and upon home products, go entirely free.

Lincoln argued that a tariff system was less intrusive than

domestic taxation: The tariff is the cheaper system, because the duties,

being collected in large parcels at a few commercial points, will

require comparatively few officers in their collection; while by the

direct tax system, the land must be literally covered with assessors and

collectors, going forth like swarms of Egyptian locusts, devouring

every blade of grass and other green thing.

William McKinley

President William McKinley stated the United States' stance under the Republican Party as:

Under free trade the trader is the master and the

producer the slave. Protection is but the law of nature, the law of

self-preservation, of self-development, of securing the highest and best

destiny of the race of man.

[It is said] that protection is immoral.... Why, if protection builds

up and elevates 63,000,000 [the U.S. population] of people, the

influence of those 63,000,000 of people elevates the rest of the world.

We cannot take a step in the pathway of progress without benefiting

mankind everywhere

[Free trade] destroys the dignity and independence of

American labor... It will take away from the people of this country who

work for a living—and the majority of them live by the sweat of their

faces—it will take from them heart and home and hope. It will be

self-destruction.

He also categorically rejected the "cheaper is better" argument:

They [free traders] say, 'Buy where

you can buy the cheapest.' That is one of their maxims… Of course, that

applies to labor as to everything else. Let me give you a maxim that is

a thousand times better than that, and it is the protection maxim: 'Buy

where you can pay the easiest.' And that spot of earth is where labor

wins its highest rewards.

They say, if you had not the Protective Tariff things would be a

little cheaper. Well, whether a thing is cheap or whether it is dear

depends on what we can earn by our daily labor. Free trade cheapens the

product by cheapening the producer. Protection cheapens the product by

elevating the producer.

The protective tariff policy of the Republicans... has made the lives of

the masses of our countrymen sweeter and brighter, and has entered the

homes of America carrying comfort and cheer and courage. It gives a

premium to human energy, and awakens the noblest aspiration in the

breasts of men. Our own experience shows that it is the best for our

citizenship and our civilization and that it opens up a higher and

better destiny for our people.

Theodore Roosevelt

President Theodore Roosevelt

believed that America's economic growth was due to the protective

tariffs, which helped her industrialize. He acknowledged this in his

State of the Union address from 1902:

The country has acquiesced in the wisdom of the

protective-tariff principle. It is exceedingly undesirable that this

system should be destroyed or that there should be violent and radical

changes therein. Our past experience shows that great prosperity in this

country has always come under a protective tariff.

Donald Trump

The Trump tariffs were imposed by executive order (not by act of Congress) during the presidency of Donald Trump as part of his economic policy. In January 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on solar panels and washing machines of 30 to 50 percent. He soon imposed tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%) from most countries. On June 1, 2018, this was extended on the European Union, Canada, and Mexico.

Separately, on May 10, the Trump administration set a tariff of 25% on

818 categories of goods imported from China worth $50 billion.

The only country which remained exempt from the steel and aluminum

tariffs was Australia. Argentinian and Brazilian aluminium tariffs were

started on December 2, 2019 in reaction to currency manipulation.