Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (professional or not), the methods of gathering information, and the organizing literary styles. Journalistic media include print, television, radio, Internet, and, in the past, newsreels.

The appropriate role for journalism varies from countries to country, as do perceptions of the profession, and the resulting status. In some nations, the news media are controlled by government and are not independent. In others, news media are independent of the government and operate as private industry. In addition, countries may have differing implementations of laws handling the freedom of speech, freedom of the press as well as slander and libel cases.

The proliferation of the Internet and smartphones has brought significant changes to the media landscape since the turn of the 21st century. This has created a shift in the consumption of print media channels, as people increasingly consume news through e-readers, smartphones, and other personal electronic devices, as opposed to the more traditional formats of newspapers, magazines, or television news channels. News organizations are challenged to fully monetize their digital wing, as well as improvise on the context in which they publish in print. Newspapers have seen print revenues sink at a faster pace than the rate of growth for digital revenues.

Production

Journalistic conventions vary by country. In the United States, journalism is produced by media organizations or by individuals. Bloggers are often regarded as journalists. The Federal Trade Commission requires that bloggers who write about products received as promotional gifts, disclose that they received the products for free. This is intended to eliminate conflicts of interest and protect consumers.

In the US, many credible news organizations are incorporated entities, have an editorial board, and exhibit separate editorial and advertising departments. Many credible news organizations, or their employees, often belong to and abide by the ethics of professional organizations such as the American Society of News Editors, the Society of Professional Journalists, Investigative Reporters & Editors, Inc., or the Online News Association. Many news organizations also have their own codes of ethics that guide journalists' professional publications. For instance, The New York Times code of standards and ethics is considered particularly rigorous.

When crafting news stories, regardless of the medium, fairness and bias are issues of concern to journalists. Some stories are intended to represent the author's own opinion; others are more neutral or feature balanced points-of-view. In a traditional print newspaper and its online version, information is organized into sections. This makes clear the distinction between content based on fact and on opinion. In other media, many of these distinctions break down. Readers should pay careful attention to headings and other design elements to ensure that they understand the journalist's intent. Opinion pieces are generally written by regular columnists or appear in a section titled "Op-ed", these reflect a journalist's own opinions and ideology. While feature stories, breaking news, and hard news stories typically make efforts to remove opinion from the copy.

According to Robert McChesney, healthy journalism in a democratic country must provide an opinion of people in power and who wish to be in power, must include a range of opinions and must regard the informational needs of all people.

Many debates centre on whether journalists are "supposed" to be "objective" and "neutral"; arguments include the fact that journalists produce news out of and as part of a particular social context, and that they are guided by professional codes of ethics and do their best to represent all legitimate points of view. Additionally, the ability to render a subject's complex and fluid narrative with sufficient accuracy is sometimes challenged by the time available to spend with subjects, the affordances or constraints of the medium used to tell the story, and the evolving nature of people's identities.

Forms

There are several forms of journalism with diverse audiences. Journalism is said to serve the role of a "fourth estate", acting as a watchdog on the workings of the government. A single publication (such as a newspaper) contains many forms of journalism, each of which may be presented in different formats. Each section of a newspaper, magazine, or website may cater to a different audience.

Some forms include:

- Access journalism – journalists who self-censor and voluntarily cease speaking about issues that might embarrass their hosts, guests, or powerful politicians or businesspersons.

- Advocacy journalism – writing to advocate particular viewpoints or influence the opinions of the audience.

- Broadcast journalism – written or spoken journalism for radio or television

- Journalists in the Radio-Canada/CBC newsroom in Montreal, Canada.

- Business journalism - tracks, records, analyzes and interprets the business, economic and financial activities and changes that take place in societies.

- Citizen journalism – participatory journalism.

- Data journalism – the practice of finding stories in numbers, and using numbers to tell stories. Data journalists may use data to support their reporting. They may also report about uses and misuses of data. The US news organization ProPublica is known as a pioneer of data journalism.

- Drone journalism – use of drones to capture journalistic footage.

- Gonzo journalism – first championed by Hunter S. Thompson, gonzo journalism is a "highly personal style of reporting".

- Interactive journalism – a type of online journalism that is presented on the web

- Investigative journalism – in-depth reporting that uncovers social problems.

- Photojournalism – the practice of telling true stories through images

- Political journalism - coverage of all aspects of politics and political science

- Sensor journalism – the use of sensors to support journalistic inquiry

- Sports journalism - writing that reports on matters pertaining to sporting topics and competitions

- Tabloid journalism – writing that is light-hearted and entertaining. Considered less legitimate than mainstream journalism.

- Yellow journalism (or sensationalism) – writing which emphasizes exaggerated claims or rumors.

- Global journalism - journalism that encompasses a global outlook focusing on intercontinental issues.

- War journalism - the covering of wars and armed conflicts

Social media

The rise of social media has drastically changed the nature of journalistic reporting, giving rise to so-called citizen journalists. In a 2014 study of journalists in the United States, 40% of participants claimed they rely on social media as a source, with over 20% depending on microblogs to collect facts. From this, the conclusion can be drawn that breaking news nowadays often stems from user-generated content, including videos and pictures posted online in social media. However, though 69.2% of the surveyed journalists agreed that social media allowed them to connect to their audience, only 30% thought it had a positive influence on news credibility. In addition to this, a recent study done by Pew Research Center shows that eight-in-ten Americans are getting their news from digital devices.

Consequently, this has resulted in arguments to reconsider journalism as a process distributed among many authors, including the socially mediating public, rather than as individual products and articles written by dedicated journalists.

Because of these changes, the credibility ratings of news outlets has reached an all-time low. A 2014 study revealed that only 22% of Americans reported a "great deal" or "quite a lot of confidence" in either television news or newspapers.

Fake news

"Fake news" is also deliberately untruthful information, which can often spread quickly on social media or by means of fake news websites. News cannot be regarded as "fake", but disinformation rather.

It is often published to intentionally mislead readers to ultimately benefit a cause, organization or an individual. A glaring example was the proliferation of fake news in social media during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and lies have been circulated under the guise of news reports to benefit specific candidates. One example is a fabricated report of Hillary Clinton's email which was published by a non-existent newspaper called The Denver Guardian. Many critics blamed Facebook for the spread of such material. Its news feed algorithm, in particular, was identified by Vox as the platform where the social media giant exercise billions of editorial decisions every day. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and TikTok are distributors of disinformation or "fake news". Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, has acknowledged the company's role in this problem: in a testimony before a combined Senate Judiciary and Commerce committee hearing on 20 April 2018, he said:

It's clear now that we didn't do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm as well. That goes for fake news, foreign interference in elections, and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy.

Readers can often evaluate credibility of news by examining the credibility of the underlying news organization.

The phrase was popularized and used by Donald Trump during his presidential campaign to discredit what he perceived as negative news coverage of his candidacy and then the presidency.

In some countries, including Turkey, Egypt, India, Bangladesh, Iran, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Montenegro, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, and Somalia journalists have been threatened or arrested for allegedly spreading fake news about the COVID-19 pandemic.

History

Antiquity

While publications reporting the news to the general public in a standardized fashion only began to appear in the 17th century and later, governments as early as Han dynasty China made use of regularly published news bulletins. Similar publications were established in the Republic of Venice in the 16th century. These bulletins, however, were intended only for government officials, and thus were not journalistic news publications in the modern sense of the term.

Early modern newspapers

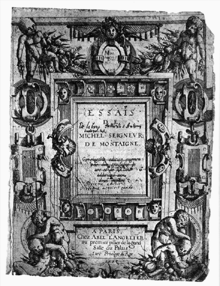

As mass-printing technologies like the printing press spread, newspapers were established to provide increasingly literate audiences with the news. The first references to privately owned newspaper publishers in China date to the late Ming dynasty in 1582. Johann Carolus's Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien, published in 1605 in Strasbourg, is often recognized as the first newspaper in Europe.

Freedom of the press was formally established in Great Britain in 1695, with Alan Rusbridger, former editor of The Guardian, stating: "licensing of the press in Britain was abolished in 1695. Remember how the freedoms won here became a model for much of the rest of the world, and be conscious how the world still watches us to see how we protect those freedoms." The first successful English daily, the Daily Courant, was published from 1702 to 1735. While journalistic enterprises were started as private ventures in some regions, such as the Holy Roman Empire and the British Empire, other countries such as France and Prussia kept tighter control of the press, treating it primarily as an outlet for government propaganda and subjecting it to uniform censorship. Other governments, such as the Russian Empire, were even more distrusting of the journalistic press and effectively banned journalistic publications until the mid-19th century. As newspaper publication became a more and more established practice, publishers would increase publication to a weekly or daily rate. Newspapers were more heavily concentrated in cities that were centres of trade, such as Amsterdam, London, and Berlin. The first newspapers in Latin America would be established in the mid-to-late 19th century.

News media and the revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries

Newspapers played a significant role in mobilizing popular support in favor of the liberal revolutions of the late 18th and 19th centuries. In the American Colonies, newspapers motivated people to revolt against British rule by publishing grievances against the British crown and republishing pamphlets by revolutionaries such as Thomas Paine, while loyalist publications motivated support against the American Revolution. News publications in the United States would remain proudly and publicly partisan throughout the 19th century. In France, political newspapers sprang up during the French Revolution, with L'Ami du peuple, edited by Jean-Paul Marat, playing a particularly famous role in arguing for the rights of the revolutionary lower classes. Napoleon would reintroduce strict censorship laws in 1800, but after his reign print publications would flourish and play an important role in political culture. As part of the Revolutions of 1848, radical liberal publications such as the Rheinische Zeitung, Pesti Hírlap, and Morgenbladet would motivate people toward deposing the aristocratic governments of Central Europe. Other liberal publications played a more moderate role: The Russian Bulletin praised Alexander II of Russia's liberal reforms in the late 19th century, and supported increased political and economic freedoms for peasants as well as the establishment of a parliamentary system in Russia. Farther to the left, socialist and communist newspapers had wide followings in France, Russia and Germany despite being outlawed by the government.

Early 20th century

China

Journalism in China before 1910 primarily served the international community. The overthrow of the old imperial regime in 1911 produced a surge in Chinese nationalism, an end to censorship, and a demand for professional, nation-wide journalism. All the major cities launched such efforts. By the late 1920s, however, there was a much greater emphasis on advertising and expanding circulation, and much less interest in the sort of advocacy journalism that had inspired the revolutionaries.

France

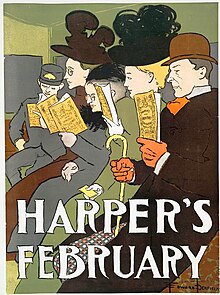

The Parisian newspapers were largely stagnant after the First World War; circulation inched up to six million a day from five million in 1910. The major postwar success story was Paris Soir; which lacked any political agenda and was dedicated to providing a mix of sensational reporting to aid circulation, and serious articles to build prestige. By 1939 its circulation was over 1.7 million, double that of its nearest rival the tabloid Le Petit Parisien. In addition to its daily paper Paris Soir sponsored a highly successful women's magazine Marie-Claire. Another magazine Match was modeled after the photojournalism of the American magazine Life.

Great Britain

By 1900 popular journalism in Britain aimed at the largest possible audience, including the working class, had proven a success and made its profits through advertising. Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (1865–1922), "More than anyone... shaped the modern press. Developments he introduced or harnessed remain central: broad contents, exploitation of advertising revenue to subsidize prices, aggressive marketing, subordinate regional markets, independence from party control. His Daily Mail held the world record for daily circulation until his death. Prime Minister Lord Salisbury quipped it was "written by office boys for office boys".

Described as "the scoop of the century", as a rookie journalist for The Daily Telegraph in 1939 Clare Hollingworth was the first to report the outbreak of World War II. While travelling from Poland to Germany, she spotted and reported German forces massed on the Polish border; The Daily Telegraph headline read: "1,000 tanks massed on Polish border "; three days later she was the first to report the German invasion of Poland.

During World War II, George Orwell worked as a journalist at The Observer for seven years, and its editor David Astor gave a copy of Orwell’s essay "Politics and the English Language"—a critique of vague, slovenly language—to every new recruit. In 2003, literary editor at the newspaper Robert McCrum wrote, "Even now, it is quoted in our style book".

India

The first newspaper of India, Hicky's Bengal Gazette, was published on 29 January 1780. This first effort at journalism enjoyed only a short stint yet it was a momentous development, as it gave birth to modern journalism in India. Following Hicky's efforts which had to be shut down just within two years of circulation, several English newspapers started publication in the aftermath. Most of them enjoyed a circulation figure of about 400 and were weeklies giving personal news items and classified advertisements about a variety of products. Later on, in the 1800s, English newspapers were started by Indian publishers with English-speaking Indians as the target audience. During that era vast differences in language was a major problem in facilitating smooth communication among the people of the country. This is because they hardly knew the languages prevalent in other parts of this vast land. However, English became a lingua franca across the country. Notable among this breed is the one named 'Bengal Gazette' started by Gangadhar Bhattacharyya in 1816.

United States

The late 19th and early 20th century in the United States saw the advent of media empires controlled by the likes of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. Realizing that they could expand their audience by abandoning politically polarized content, thus making more money off of advertising, American newspapers began to abandon their partisan politics in favor of less political reporting starting around 1900. Newspapers of this era embraced sensationalized reporting and larger headline typefaces and layouts, a style that would become dubbed "yellow journalism". Newspaper publishing became much more heavily professionalized in this era, and issues of writing quality and workroom discipline saw vast improvement. This era saw the establishment of freedom of the press as a legal norm, as President Theodore Roosevelt tried and failed to sue newspapers for reporting corruption in his handling of the purchase of the Panama Canal. Still, critics note that although government's ability to suppress journalistic speech is heavily limited, the concentration of newspaper (and general media) ownership in the hands of a small number of private business owners leads to other biases in reporting and media self-censorship that benefits the interests of corporations and the government.

African-American press

The rampant discrimination and segregation against African-Americans led to the founding their own daily and weekly newspapers, especially in large cities. While the first Black newspapers in America were established in the early 19th century, in the 20th century these newspapers truly flourished in major cities, with publishers playing a major role in politics and business affairs. Representative leaders included Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1870–1940), publisher of the Chicago Defender; John Mitchell, Jr. (1863–1929), editor of the Richmond Planet and president of the National Afro-American Press Association; Anthony Overton (1865–1946), publisher of the Chicago Bee, and Robert Lee Vann (1879–1940), the publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier.

College

Although it is not completely necessary to have attended college to be a journalist, over the past few years it has become more common to attend. With this becoming more popular, jobs are starting to require a degree to be hired. The first school of Journalism opened as part of the University of Missouri in 1908. In the History Of Journalism page, it goes into depth on how journalism has evolved into what it is today. As of right now, there are a couple different routes one can take if interested in journalism. If one wanting to expand their skills as a journalist, there are many college courses and workshops one can take. If going the full college route, the average time is takes to graduate with a journalism degree is 4 years.

The top 5 ranked journalism schools in the US for the school year of 2022 are: 1. Washington and Lee University. 2. Northwestern University. 3. Georgetown University. 4. Columbia University in the City of New York. 5. University of Wisconsin - Madison.

Writing for experts or for ordinary citizens

In the 1920s in the United States, as newspapers dropped their blatant partisanship in search of new subscribers, political analyst Walter Lippmann and philosopher John Dewey debated the role of journalism in a democracy. Their differing philosophies still characterize an ongoing debate about the role of journalism in society. Lippmann's views prevailed for decades, helping to bolster the Progressives' confidence in decision-making by experts, with the general public standing by. Lippmann argued that high-powered journalism was wasted on ordinary citizens, but was of genuine value to an elite class of administrators and experts. Dewey, on the other hand, believed not only that the public was capable of understanding the issues created or responded to by the elite, but also that it was in the public forum that decisions should be made after discussion and debate. When issues were thoroughly vetted, then the best ideas would bubble to the surface. The danger of demagoguery and false news did not trouble Dewey. His faith in popular democracy has been implemented in various degrees, and is now known as "community journalism". The 1920s debate has been endlessly repeated across the globe, as journalists wrestle with their roles.

Radio

Radio broadcasting increased in popularity starting in the 1920s, becoming widespread in the 1930s. While most radio programming was oriented toward music, sports, and entertainment, radio also broadcast speeches and occasional news programming. Radio reached the peak of its importance during World War II, as radio and newsreels were major sources of up-to-date information on the ongoing war. In the Soviet Union, radio would be heavily utilized by the state to broadcast political speeches by leadership. These broadcasts would very rarely have any additional editorial content or analysis, setting them apart from modern news reporting. The radio would however soon be eclipsed by broadcast television starting in the 1950s.

Television

Starting in the 1940s, United States broadcast television channels would air 10-to-15-minute segments of news programming one or two times per evening. The era of live-TV news coverage would begin in the 1960s with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, broadcast and reported to live on a variety of nationally syndicated television channels. During the 60s and 70s, television channels would begin adding regular morning or midday news shows. Starting in 1980 with the establishment of CNN, news channels began providing 24-hour news coverage, a format which persists through today.

Digital age

The role and status of journalism, as well as mass media, has undergone changes over the last two decades, together with the advancement of digital technology and publication of news on the Internet. This has created a shift in the consumption of print media channels, as people increasingly consume news through e-readers, smartphones, and other electronic devices. News organizations are challenged to fully monetize their digital wing, as well as improvise on the context in which they publish in print. Newspapers have seen print revenues sink at a faster pace than the rate of growth for digital revenues.

Notably, in the American media landscape, newsrooms have reduced their staff and coverage as traditional media channels, such as television, grappling with declining audiences. For example, between 2007 and 2012, CNN edited its story packages into nearly half of their original time length.

The compactness in coverage has been linked to broad audience attrition. According to the Pew Research Center, the circulation for U.S. newspapers has fallen sharply in the 21st century. The digital era also introduced journalism whose development is done by ordinary citizens, with the rise of citizen journalism being possible through the Internet. Using video camera-equipped smartphones, active citizens are now enabled to record footage of news events and upload them onto channels like YouTube (which is often discovered and used by mainstream news media outlets). News from a variety of online sources, like blogs and other social media, results in a wider choice of official and unofficial sources, rather than only traditional media organizations.

Demographics in 2016

A worldwide sample of 27,500 journalists in 67 countries in 2012-2016 produced the following profile:

- 57 percent male;

- Mean age of 38

- Mean years of experience:13

- College degree: 56 percent; graduate degree: 29 percent

- 61 percent specialized in journalism/communications at college

- 62 percent identified as generalists and 23 percent as hard-news beat journalists

- 47 percent were members of a professional association

- 80 percent worked full-time

- 50 percent worked in print, 23 percent in television, 17 percent in radio, and 16 percent online.

Ethics and standards

While various existing codes have some differences, most share common elements including the principles of – truthfulness, accuracy, objectivity, impartiality, fairness and public accountability – as these apply to the acquisition of newsworthy information and its subsequent dissemination to the public.

Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel propose several guidelines for journalists in their book The Elements of Journalism. Their view is that journalism's first loyalty is to the citizenry and that journalists are thus obliged to tell the truth and must serve as an independent monitor of powerful individuals and institutions within society. In this view, the essence of journalism is to provide citizens with reliable information through the discipline of verification.

Some journalistic Codes of Ethics, notably the European ones, also include a concern with discriminatory references in news based on race, religion, sexual orientation, and physical or mental disabilities. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe approved in 1993 Resolution 1003 on the Ethics of Journalism which recommends journalists to respect the presumption of innocence, in particular in cases that are still sub judice.

In the UK, all newspapers are bound by the Code of Practice of the Independent Press Standards Organisation. This includes points like respecting people's privacy and ensuring accuracy. However, the Media Standards Trust has criticized the PCC, claiming it needs to be radically changed to secure the public trust of newspapers.

This is in stark contrast to the media climate prior to the 20th century, where the media market was dominated by smaller newspapers and pamphleteers who usually had an overt and often radical agenda, with no presumption of balance or objectivity.

Because of the pressure on journalists to report news promptly and before their competitors, factual errors occur more frequently than in writing produced and edited under less time pressure. Thus a typical issue of a major daily newspaper may contain several corrections of articles published the previous day. Perhaps the most famous journalistic mistake caused by time pressure was the Dewey Defeats Truman edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune, based on early election returns that failed to anticipate the actual result of the 1948 US presidential election.

Codes of ethics

There are over 242 codes of ethics in journalism that vary across various regions of the world. The codes of ethics are created through an interaction of different groups of people such as the public and journalists themselves. Most of the codes of ethics serve as a representation of the economic and political beliefs of the society where the code was written. Despite the fact that there are a variety of codes of ethics, some of the core elements present in all codes are: remaining objective, providing the truth, and being honest.

Journalism does not have a universal code of conduct; individuals are not legally obliged to follow a certain set of rules like a doctor or a lawyer does. There have been discussions for creating a universal code of conduct in journalism. One suggestion centers on having three claims for credibility, justifiable consequence, and the claim of humanity. Within the claim of credibility, journalists are expected to provide the public with reliable and trustworthy information, and allowing the public to question the nature of the information and its acquisition. The second claim of justifiable consequences centers on weighing the benefits and detriments of a potentially harmful story and acting accordingly. An example of justifiable consequence is exposing a professional with dubious practices; on the other hand, acting within justifiable consequence means writing compassionately about a family in mourning. The third claim is the claim of humanity which states that journalists are writing for a global population and therefore must serve everyone globally in their work, avoiding smaller loyalties to country, city, etc.

Legal status

Governments have widely varying policies and practices towards journalists, which control what they can research and write, and what press organizations can publish. Some governments guarantee the freedom of the press; while other nations severely restrict what journalists can research or publish.

Journalists in many nations have some privileges that members of the general public do not, including better access to public events, crime scenes and press conferences, and to extended interviews with public officials, celebrities and others in the public eye.

Journalists who elect to cover conflicts, whether wars between nations or insurgencies within nations, often give up any expectation of protection by government, if not giving up their rights to protection from the government. Journalists who are captured or detained during a conflict are expected to be treated as civilians and to be released to their national government. Many governments around the world target journalists for intimidation, harassment, and violence because of the nature of their work.

Right to protect confidentiality of sources

Journalists' interaction with sources sometimes involves confidentiality, an extension of freedom of the press giving journalists a legal protection to keep the identity of a confidential informant private even when demanded by police or prosecutors; withholding their sources can land journalists in contempt of court, or in jail.

In the United States, there is no right to protect sources in a federal court. However, federal courts will refuse to force journalists to reveal their sources, unless the information the court seeks is highly relevant to the case and there's no other way to get it. State courts provide varying degrees of such protection. Journalists who refuse to testify even when ordered to can be found in contempt of court and fined or jailed. On the journalistic side of keeping sources confidential, there is also a risk to the journalist's credibility because there can be no actual confirmation of whether the information is valid. As such it is highly discouraged for journalists to have confidential sources.