From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form non-fiction. Using extensive imagery, reporters interpolate subjective language within facts whilst immersing themselves in the stories as they reported and wrote them. In traditional journalism, however, the journalist is "invisible"; facts are reported objectively.

The term was codified with its current meaning by Tom Wolfe in a 1973 collection of journalism articles he published as The New Journalism, which included works by himself, Truman Capote, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, Terry Southern, Robert Christgau, Gay Talese and others.

Articles in the New Journalism style tended not to be found in newspapers, but in magazines such as The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, CoEvolution Quarterly, Esquire, New York, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and for a short while in the early 1970s, Scanlan's Monthly.

Contemporary journalists and writers questioned the "currency" of New Journalism and its qualification as a distinct genre. The subjective nature of New Journalism received extensive exploration: one critic suggested the genre's practitioners functioned more as sociologists and psychoanalysts than as journalists. Criticism has been leveled at numerous individual writers in the genre, as well.

Precursors and alternate uses of the term

Various people and tendencies throughout the history of American journalism have been labeled "new journalism". Robert E. Park, for instance, in his Natural History of the Newspaper, referred to the advent of the penny press in the 1830s as "new journalism". Likewise, the appearance of the yellow press—papers such as Joseph Pulitzer's New York World in the 1880s—led journalists and historians to proclaim that a "New Journalism" had been created. Ault and Emery, for instance, said "[i]ndustrialization and urbanization changed the face of America during the latter half of the Nineteenth century, and its newspapers entered an era known as that of the 'New Journalism.'" John Hohenberg, in The Professional Journalist (1960), called the interpretive reporting which developed after World War II a "new journalism which not only seeks to explain as well as to inform; it even dares to teach, to measure, to evaluate."

During the 1960s and 1970s, the term enjoyed widespread popularity, often with meanings bearing manifestly little or no connection with one another. Although James E. Murphy noted that "...most uses of the term seem to refer to something no more specific than vague new directions in journalism", Curtis D. MacDougal devoted the preface of the sixth edition of his Interpretative Reporting to New Journalism and cataloged many of the contemporary definitions: "Activist, advocacy, participatory, tell-it-as-you-see-it, sensitivity, investigative, saturation, humanistic, reformist and a few more."

The Magic Writing Machine—Student Probes of the New Journalism, a collection edited and introduced by Everette E. Dennis, came up with six categories, labelled new nonfiction (reportage), alternative journalism ("modern muckraking"), advocacy journalism, underground journalism and precision journalism. Michael Johnson's The New Journalism addresses itself to three phenomena: the underground press, the artists of nonfiction, and changes in the established media.

First usage

Matthew Arnold is credited with coining the term "New Journalism" in 1887, which went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire. However, at the time, the target of Arnold's irritation was not Northcliffe, but the sensational journalism of Pall Mall Gazette editor W.T. Stead. He strongly disapproved of the muck-raking Stead, and declared that, under this editor, "the P.M.G., whatever may be its merits, is fast ceasing to be literature." Stead himself called his brand of journalism 'Government by Journalism'

Early development, 1960s

How and when the term New Journalism began to refer to a genre is not clear. Tom Wolfe, a practitioner and principal advocate of the form, wrote in at least two articles in 1972 that he had no idea of where it began. Trying to shed light on the matter, literary critic Seymour Krim offered his explanation in 1973.

I'm certain that [Pete] Hamill first used the expression. In about April of 1965 he called me at Nugget Magazine, where I was editorial director, and told me he wanted to write an article about new New Journalism. It was to be about the exciting things being done in the old reporting genre by Talese, Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin. He never wrote the piece, so far as I know, but I began using the expression in conversation and writing. It was picked up and stuck.

But wherever and whenever the term arose, there is evidence of some literary experimentation in the early 1960s, as when Norman Mailer broke away from fiction to write "Superman Comes to the Supermarket". A report of John F. Kennedy's nomination that year, the piece established a precedent which Mailer would later build on in his 1968 convention coverage (Miami and the Siege of Chicago) and in other nonfiction as well.

Wolfe wrote that his first acquaintance with a new style of reporting came in a 1962 Esquire article about Joe Louis by Gay Talese. "'Joe Louis at Fifty'a wasn't like a magazine article at all. It was like a short story. It began with a scene, an intimate confrontation between Louis and his third wife..." Wolfe said Talese was the first to apply fiction techniques to reporting. Esquire claimed credit as the seedbed for these new techniques. Esquire editor Harold Hayes later wrote that "in the Sixties, events seemed to move too swiftly to allow the osmotic process of art to keep abreast, and when we found a good novelist we immediately sought to seduce him with the sweet mysteries of current events." Soon others, notably New York, followed Esquire's lead, and the style eventually infected other magazines and then books.

1970s

Much of the criticism favorable to this New Journalism came from the writers themselves. Talese and Wolfe, in a panel discussion cited earlier, asserted that, although what they wrote may look like fiction, it was indeed reporting: "Fact reporting, leg work," Talese called it.

Wolfe, in Esquire for December, 1972, hailed the replacement of the novel by the New Journalism as literature's "main event" and detailed the points of similarity and contrast between the New Journalism and the novel. The four techniques of realism that he and the other New Journalists employed, he wrote, had been the sole province of novelists and other literati. They are scene-by-scene construction, full record of dialogue, third-person point of view and the manifold incidental details to round out character (i.e., descriptive incidentals). The result:

... is a form that is not merely like a novel. It consumes devices that happen to have originated with the novel and mixes them with every other device known to prose. And all the while, quite beyond matters of technique, it enjoys an advantage so obvious, so built-in, one almost forgets what power it has: the simple fact that the reader knows all this actually happened. The disclaimers have been erased. The screen is gone. The writer is one step closer to the absolute involvement of the reader that Henry James and James Joyce dreamed of but never achieved.

The essential difference between the new nonfiction and conventional reporting is, he said, that the basic unit of reporting was no longer the datum or piece of information but the scene. Scene is what underlies "the sophisticated strategies of prose."

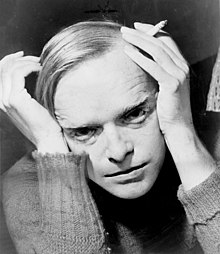

The first of the new breed of nonfiction writers to receive wide notoriety was Truman Capote, whose 1965 best-seller, In Cold Blood, was a detailed narrative of the murder of a Kansas farm family. Capote culled material from some 6,000 pages of notes. The book brought its author instant celebrity. Capote announced that he had created a new art form which he labelled the "nonfiction novel."

I've always had the theory that reportage is the great unexplored art form... I've had this theory that a factual piece of work could explore whole new dimensions in writing that would have a double effect fiction does not have—the very fact of its being true, every word of it's true, would add a double contribution of strength and impact

Capote continued to stress that he was a literary artist, not a journalist, but critics hailed the book as a classic example of New Journalism.

Wolfe's The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, whose introduction and title story, according to James E. Murphy, "emerged as a manifesto of sorts for the nonfiction genre," was published the same year. In his introduction, Wolfe wrote that he encountered trouble fashioning an Esquire article out of material on a custom car extravaganza in Los Angeles, in 1963. Finding he could not do justice to the subject in magazine article format, he wrote a letter to his editor, Byron Dobell, which grew into a 49-page reportb detailing the custom car world, complete with scene construction, dialogue and flamboyant description. Esquire ran the letter, striking out "Dear Byron." and it became Wolfe's maiden effort as a New Journalist.

In an article entitled "The Personal Voice and the Impersonal Eye", Dan Wakefield acclaimed the nonfiction of Capote and Wolfe as elevating reporting to the level of literature, terming that work and some of Norman Mailer's nonfiction a journalistic breakthrough: reporting "charged with the energy of art". A review by Jack Newfield of Dick Schaap's Turned On saw the book as a good example of budding tradition in American journalism which rejected many of the constraints of conventional reporting:

This new genre defines itself by claiming many of the techniques that were once the unchallenged terrain of the novelist: tension, symbol, cadence, irony, prosody, imagination.

A 1968 review of Wolfe's The Pump House Gang and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test said Wolfe and Mailer were applying "the imaginative resources of fiction" to the world around them and termed such creative journalism "hystory" to connote their involvement in what they reported. Talese in 1970, in his Author's Note to Fame and Obscurity, a collection of his pieces from the 1960s, wrote:

The new journalism, though often reading like fiction, is not fiction. It is, or should be, as reliable as the most reliable reportage although it seeks a larger truth than is possible through the mere compilation of verifiable facts, the use of direct quotations, and adherence to the rigid organizational style of the older form.

Seymour Krim's Shake It for the World, Smartass, which appeared in 1970, contained "An Open Letter to Norman Mailer" which defined New Journalism as "a free nonfictional prose that uses every resource of the best fiction." In "The Newspaper As Literature/Literature As Leadership", he called journalism "the de facto literature" of the majority, a synthesis of journalism and literature that the book's postscript called "journalit." In 1972, in "An Enemy of the Novel", Krim identified his own fictional roots and declared that the needs of the time compelled him to move beyond fiction to a more "direct" communication to which he promised to bring all of fiction's resources.

David McHam, in an article titled "The Authentic New Journalists", distinguished the nonfiction reportage of Capote, Wolfe and others from other, more generic interpretations of New Journalism. Also in 1971, William L. Rivers disparaged the former and embraced the latter, concluding, "In some hands, they add a flavor and a humanity to journalistic writing that push it into the realm of art." Charles Brown in 1972 reviewed much that had been written as New Journalism and about New Journalism by Capote, Wolfe, Mailer and others and labelled the genre "New Art Journalism", which allowed him to test it both as art and as journalism. He concluded that the new literary form was useful only in the hands of literary artists of great talent.

In the first of two pieces by Wolfe in New York detailing the growth of the new nonfiction and its techniques, Wolfe returned to the fortuitous circumstances surrounding the construction of Kandy-Kolored and added:

Its virtue was precisely in showing me the possibility of there being something "new" in journalism. What interested me was not simply the discovery that it was possible to write accurate nonfiction with techniques usually associated with novels and short stories. It was that—plus. It was the discovery that it was possible in nonfiction, in journalism, to use any literary device, from the traditional dialogisms of the essay to stream-of-consciousness...

1980s

In the eighties, the use of New Journalism saw a decline, several of the old trailblazers still used fiction techniques in their nonfiction books. However, younger writers in Esquire and Rolling Stone, where the style had flourished in the two earlier decades, shifted away from the New Journalism. Fiction techniques had not been abandoned by these writers, but they were used sparingly and less flamboyantly.

"Whatever happened to the New Journalism?" wondered Thomas Powers in a 1975 issue of Commonweal. In 1981, Joe Nocera published a postmortem in Washington Monthly blaming its demise on the journalistic liberties taken by Hunter S. Thompson. Regardless of the culprit, less than a decade after Wolfe's 1973 New Journalism anthology, the consensus was that New Journalism was dead.

Characteristics

As a literary genre, New Journalism has certain technical characteristics. It is an artistic, creative, literary reporting form with three basic traits: dramatic literary techniques; intensive reporting; and reporting of generally acknowledged subjectivity.

As subjective journalism

Pervading many of the specific interpretations of New Journalism is a posture of subjectivity. Subjectivism is thus a common element among many (though not all) of its definitions. In contrast to a conventional journalistic striving for an objectivity, subjective journalism allows for the writer's opinion, ideas or involvement to creep into the story.

Much of the critical literature concerns itself with a strain of subjectivism which may be called activism in news reporting. In 1970, Gerald Grant wrote disparagingly in Columbia Journalism Review of a "New Journalism of passion and advocacy" and in the Saturday Review Hohenberg discussed "The Journalist As Missionary" For Masterson in 1971, "The New Journalism" provided a forum for discussion of journalistic and social activism. In another 1971 article under the same title, Ridgeway called the counterculture magazines such as The New Republic and Ramparts and the American underground press New Journalism.

Another version of subjectivism in reporting is what is sometimes called participatory reporting. Robert Stein, in Media Power, defines New Journalism as "A form of participatory reporting that evolved in parallel with participatory politics..."

As form and technique

The above interpretations of New Journalism view it as an attitude toward the practice of journalism. But a significant portion of the critical literature deals with form and technique. Critical comment dealing with New Journalism as a literary-journalistic genre (a distinct type of category of literary work grouped according to similar and technical characteristics) treats it as the new nonfiction. Its traits are extracted from the criticism written by those who claim to practice it and by others. Admittedly it is hard to isolate from a number of the more generic meanings.

The new nonfiction were sometimes taken for advocacy of subjective journalism. A 1972 article by Dennis Chase defines New Journalism as a subjective journalism emphasizing "truth" over "facts" but uses major nonfiction stylists as its example.

As intensive reportage

Although much of the critical literature discussed the use of literary or fictional techniques as the basis for a New Journalism, critics also referred to the form as stemming from intensive reporting. Stein, for instance, found the key to New Journalism not its fictionlike form but the "saturation reporting" which precedes it, the result of the writer's immersion in his subject. Consequently, Stein concluded, the writer is as much part of his story as is the subject and he thus linked saturation reporting with subjectivity. For him, New Journalism is inconsistent with objectivity or accuracy.

However, others have argued that total immersion enhances accuracy. As Wolfe put the case:

I am the first to agree that the New Journalism should be as accurate as traditional journalism. In fact my claims for the New Journalism, and my demands upon it, go far beyond that. I contend that it has already proven itself more accurate than traditional journalism—which unfortunately is saying but so much...

Wolfe coined "saturation reporting" in his Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors article. After citing the opening paragraphs of Talese's Joe Louis piece, he confessed believing that Talese had "piped" or faked the story, only later to be convinced, after learning that Talese so deeply delved into the subject, that he could report entire scenes and dialogues.

The basic units of reporting are no longer who-what-when-where-how and why but whole scenes and stretches of dialogue. The New Journalism involves a depth of reporting and an attention to the most minute facts and details that most newspapermen, even the most experienced, have never dreamed of.

In his "Birth of the New Journalism" in New York, Wolfe returned to the subject, which he here described as a depth of information never before demanded in newspaper work. The New Journalist, he said, must stay with his subject for days and weeks at a stretch. In Wolfe's Esquire piece, saturation became the "Locker Room Genre" of intensive digging into the lives and personalities of one's subject, in contrast to the aloof and genteel tradition of the essayists and "The Literary Gentlemen in the Grandstand."

For Talese, intensive reportage took the form of interior monologue to discover from his subjects what they were thinking, not, he said in a panel discussion reported in Writer's Digest, merely reporting what people did and said.

Wolfe identified the four main devices New Journalists borrowed from literary fiction:

- Telling the story using scenes rather than historical narrative as much as possible

- Dialogue in full (conversational speech rather than quotations and statements)

- Point-of-view (present every scene through the eyes of a particular character)

- Recording everyday details such as behavior, possessions, friends and family (which indicate the "status life" of the character)

Despite these elements, New Journalism is not fiction. It maintains elements of reporting including strict adherence to factual accuracy and the writer being the primary source. To get "inside the head" of a character, the journalist asks the subject what they were thinking or how they felt.

Writers and editors

There is little consensus on which writers can be definitively categorized as New Journalists. In The New Journalism: A Critical Perspective, Murphy writes that New Journalism "involves a more or less well defined group of writers," who are "stylistically unique" but share "common formal elements." Among the most prominent New Journalists, Murphy lists: Jimmy Breslin, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, David Halberstam, Pete Hamill, Larry L. King, Norman Mailer, Joe McGinniss, Rex Reed, Mike Royko, John Sack, Dick Schaap, Terry Southern, Gail Sheehy, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Dan Wakefield and Tom Wolfe. In The New Journalism, the editors E.W Johnson and Tom Wolfe, include George Plimpton for Paper Lion, Life writer James Mills and Robert Christgau, et cetera, in the corps. Christgau, however, stated in a 2001 interview that he does not see himself as a New Journalist.

The editors Clay Felker, Normand Poirier and Harold Hayes also contributed to the rise of New Journalism.

Criticism

While many praised the New Journalist's style of writing, Wolfe et al., also received severe criticism from contemporary journalists and writers. Essentially two different charges were leveled against New Journalism: criticism against it as a distinct genre and criticism against it as a new form.

Robert Stein believed that "In the New Journalism the eye of the beholder is all—or almost all," and in 1971 Philip M. Howard, wrote that the new nonfiction writers rejected objectivity in favor of a more personal, subjective reportage. This parallels much of what Wakefield said in his 1966 Atlantic article.

The important and interesting and hopeful trend to me in the new journalism is its personal nature—not in the sense of personal attacks, but in the presence of the reporter himself and the significance of his own involvement. This is sometimes felt to be egotistical, and the frank identification of the author, especially as the "I" instead of merely the impersonal "eye" is often frowned upon and taken as proof of "subjectivity", which is the opposite of the usual journalistic pretense.

And in spite of the fact that Capote believed in the objective accuracy of In Cold Blood and strove to keep himself totally out of the narrative, one reviewer found in the book the "tendency among writers to resort to subjective sociology, on the other hand, or to super-creative reportage, on the other." Charles Self termed this characteristic of New Journalism as "admitted" subjectivity, whether first-person or third-person, and acknowledged the subjectivity inherent in his account.

Lester Markel polemically criticized New Journalism in the Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, he rejected the claim to greater in-depth reporting and labelled the writers "factual fictionists" and "deep-see reporters." He feared they were performing as sociologists and psychoanalysts rather than as journalists. The lack of source footnotes and bibliographies in most works of New Journalism is often cited by critics as showing a lack of intellectual rigor, verifiability, and even author laziness and sloppiness.

More reasoned, though still essentially negative, Arlen in his 1972 "Notes on the New Journalism", put the New Journalism into a larger socio-historical perspective by tracing the techniques from earlier writers and from the constraints and opportunities of the current age. But much of the more routine New Journalism "consists in exercises by writer ... in gripping and controlling and confronting a subject within the journalist's own temperament. Presumably," he wrote, "this is the 'novelistic technique.'" However, he conceded that the best of this work had "considerably expanded the possibilities of journalism."

Much negative criticism of New Journalism were directed at individual writers. For example, Cynthia Ozick asserted in The New Republic, that Capote in In Cold Blood was doing little more than trying to devise a form: "One more esthetic manipulation." Sheed offered, in "A Fun-House Mirror", a witty refutation of Wolfe's claim that he takes on the expression and the guise of whomever he is writing about. "The Truman Capotes may hold up a tolerably clear glass to nature," he wrote, "but Wolfe holds up a fun-house mirror, and I for one don't give a hoot whether he calls the reflection fact or fiction."

"Parajournalism" and the New Yorker affair

Among the hostile critics of the New Journalism were Dwight Macdonald, whose most vocal criticism comprised a chapter in what became known as "the New Yorker affair" of 1965. Wolfe had written a two-part semi-fictional parody in New York of The New Yorker and its editor, William Shawn. Reaction, notably from New Yorker writers, was loud and prolonged,c but the most significant reaction came from Macdonald, who counterattacked in two articles in The New York Review of Books. In the first, Macdonald termed Wolfe's approach "parajournalism" and applied it to all similar styles. "Parajournalism," Macdonald wrote,

... seems to be journalism—"the collection and dissemination of current news"—but the appearance is deceptive. It is a bastard form, having it both ways, exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.

The New Yorker parody, he added, "... revealed the ugly side of Parajournalism when it tries to be serious."

In his second article, MacDonald addressed himself to the accuracy of Wolfe's report. He charged that Wolfe "takes a middle course, shifting gears between fact and fantasy, spoof and reportage, until nobody knows which end is, at the moment, up". New Yorker writers Renata Adler and Gerald Jonas joined the fray in the Winter 1966 issue of Columbia Journalism Review.

Wolfe himself returned to the affair a full seven years later, devoting the second of his two February New York articles (1972) to his detractors but not to dispute their attack on his factual accuracy. He argued that most of the contentions arose because for traditional literati nonfiction should not succeed—which his nonfiction obviously had.

Gail Sheehy and "Redpants"

In The New Journalism: A Critical Perspective, Murphy writes, "Partly because Wolfe took liberties with the facts in his New Yorker parody, New Journalism began to get a reputation for juggling the facts in the search for truth, fictionalizing some details to get a larger 'reality.'" Widely criticized was the technique of the composite character, the most notorious example of which was "Redpants," a presumed prostitute whom Gail Sheehy wrote about in New York in a series on that city's sexual subculture. When it later became known that the character was distilled from a number of prostitutes, there was an outcry against Sheehy's method and, by extension, to the credibility of all of New Journalism. In the Wall Street Journal, one critic wrote:

It's all part of the New Journalism, or the Now Journalism, and it's practiced widely these days. Some editors and reporters vigorously defend it. Others just as vigorously attack it. No one has polled the reader, but whether he approves or disapproves, it's getting harder and harder for him to know what he can believe.

Newsweek reported that critics felt Sheehy's energies were better suited to fiction than fact. John Tebbel, in an article in Saturday Review, although treating New Journalism in its more generic sense as new a trend, chided it for the fictional technique of narrative leads which the new nonfiction writers had introduced into journalism and deplored its use in newspapers.

Criticism against New Journalism as a distinct genre

Newfield, in 1972, changed his attitude following his earlier, 1967, review of Wolfe. "New Journalism does not exist", the later article titled "Is there a 'new journalism'?" says. "It is a false category. There is only good writing and bad writing, smart ideas and dumb ideas, hard work and laziness." While the practice of journalism had improved during the past fifteen years, he argued, it was because of an influx of good writers notable for unique styles, not because they belonged to any school or movement.

Jimmy Breslin, who is often labelled a New Journalist, took the same view: "Believe me, there is no new journalism. It is a gimmick to say there is ... Story telling is older than the alphabet and that is what it is all about."