Overall mortality and morbidity

A

strong inverse correlation between early life intelligence and

mortality has been shown across different populations, in different

countries, and in different epochs."

A study of one million Swedish men found showed "a strong link between cognitive ability and the risk of death."

The strong correlation between intelligence and mortality has

raised questions as to how better public education could delay

mortality.

There is a known inverse correlation between socioeconomic

position and health. A 2006 study found that controlling for IQ caused a

marked reduction in this association.

Research in Scotland

has shown that a 15-point lower IQ meant people had a fifth less chance

of seeing their 76th birthday, while those with a 30-point disadvantage

were 37% less likely than those with a higher IQ to live that long.

Another Scottish study found that once individuals had reached

old age (79 in this study), it was no longer childhood intelligence or

current intelligence scores that best predicted mortality but the

relative decline in cognitive abilities from age 11 to age 79. They also

found that fluid abilities were better predictors of survival in old age than crystallized abilities.

The relationship between childhood intelligence and mortality has even been found to hold for gifted children,

those with an intelligence over 135. A 15-point increase in

intelligence was associated with a decreased risk of mortality of 32%.

This relationship was present until an intelligence score of 163 at

which point there was no further advantage of a higher intelligence on

mortality risk.

A meta-analysis of the relationship between intelligence and mortality found that there was a 24% increase in mortality for a 1SD

(15 point) drop in IQ score. This meta-analysis also concluded that the

association between intelligence and mortality was similar for men and

women despite sex differences in disease prevalence and life

expectancies.

A whole population follow-up over 68 years showed that the

association with overall mortality was also present for most major

causes of death. The exceptions were cancers unrelated to smoking and

suicide.

There is also a strong inverse correlation between intelligence

and adult morbidity. Long term sick leave in adulthood has been shown to

be related to lower cognitive abilities, as has likelihood of receiving a disability pension.

Physical illness

Coronary heart disease

Among the findings of cognitive epidemiology is that men with a higher IQ have less risk of dying from coronary heart disease. The association is attenuated, but not removed, when controlling for socio-economic variables, such as educational attainment or income. This suggests that IQ may be an independent risk factor for mortality.

One study found that low verbal, visuospatial and arithmetic scores were particularly good predictors of coronary heart disease.

Atherosclerosis

or thickening of the artery walls due to fatty substances is a major

factor in heart disease and some forms of stroke. It has also been

linked to lower IQ.

Obesity

Lower intelligence in childhood and adolescence correlates with an increased risk of obesity.

One study found that a 15-point increase in intelligence score was

associated with a 24% decrease in risk of obesity at age 51.

The direction of this relationship has been greatly debated with some

arguing that obesity causes lower intelligence, however, recent studies

have indicated that a lower intelligence increases the chances of

obesity.

Blood pressure

Higher intelligence in childhood and adulthood has been linked to lower blood pressure and a lower risk of hypertension.

Stroke

Strong evidence has been found in support of a link between intelligence and stroke,

with those with lower intelligence being at greater risk of stroke. One

study found visuospatial reasoning was the best predictor of stroke

compared to other cognitive tests.

Further this study found that controlling for socioeconomic variables

did little to attenuate the relationship between visuospatial reasoning

and stroke.

Cancer

Studies exploring the link between cancer

and intelligence have come to varying conclusions. A few studies, which

were mostly small have found an increased risk of death from cancer in

those with lower intelligence. Other studies have found an increased risk of skin cancer with higher intelligence. However, on the whole most studies have found no consistent link between cancer and intelligence.

Psychiatric

Bipolar disorder and intelligence

Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterized by periods of elevated mood known as mania or hypomania and periods of depression. Anecdotal and biographical evidence popularized the idea that sufferers of bipolar disorder are tormented geniuses that are uniquely equipped with high levels of creativity and superior intelligence. Bipolar disorder is relatively rare, affecting only 2.5% of the population, as it is also the case with especially high intelligence.

The uncommon nature of the disorder and rarity of high IQ pose unique

challenges in sourcing large enough samples that are required to conduct

a rigorous analysis of the association between intelligence and bipolar

disorder.

Nevertheless, there has been much progress starting from the mid-90s,

with several studies beginning to shed a light on this elusive

relationship.

One such study examined individual compulsory school grades of

Swedish pupils between the ages of 15 and 16 to find that individuals

with excellent school performance had a nearly four times increased rate

to develop a variation of bipolar disorder

later in life than those with average grades. The same study also found

that students with lowest grades were at a moderately increased risk of

developing bipolar disorder with nearly a twofold increase when

compared to average-grade students.

A New Zealand study of 1,037 males and females from the 1972–1973 birth cohort of Dunedin suggests that lower childhood IQs were associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia spectrum disorders, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder

in adulthood; whereas higher childhood IQ predicted an increased

likelihood of mania. This study only included eight cases of mania and

thus should only be used to support already existing trends.

In the largest study yet published analyzing the relationship between bipolar disorder and intelligence, Edinburgh University

researchers looked at the link between intelligence and bipolar

disorder in a sample of over one million men enlisted in the Swedish

army during a 22-year follow-up period. Regression results showed that

the risk of hospitalization for bipolar disorder with comorbidity

to other mental health illnesses decreased in a linear pattern with an

increase in IQ. However, when researchers restricted the analysis to men

without any psychiatric comorbidity, the relationship between bipolar

disorder and intelligence followed a J-curve.

Note:

Illustrative graph only – not based on actual data points, but

representative of established research on the relationship between IQ

and Bipolar Disorders. Please refer to Gale for further information.

These findings suggest that men of extremely high intelligence are at a

higher risk of experiencing bipolar in its purest form, and demands

future investigation of the correlation between extreme brightness and pure bipolar.

Additional support of a potential association between high

intelligence and bipolar disorder comes from biographical and anecdotal

evidence, and primarily focus on the relationship between creativity and bipolar disorder. Doctor Kay Redfield Jamison

has been a prolific writer on the subject publishing several articles

and an extensive book analyzing the relationship between the artistic

temperament and mood disorders. Although a link between bipolar disorder and creativity has been established, there is no confirming evidence suggesting any significant relationship between creativity and intelligence.

Additionally, even though some of these studies suggest a potential

benefit to bipolar disorder in regards to intelligence, there is

significant amount of controversy as to the individual and societal cost

of this presumed intellectual advantage. Bipolar disorder is

characterized by periods of immense pain and suffering, self-destructive

behaviors, and has one of the highest mortality rates of all mental

illnesses.

Schizophrenia and cognition

Schizophrenia is chronic and disabling mental illness that is characterized by abnormal behavior, psychotic episodes and inability to recognize between reality and fantasy.

Even though schizophrenia can severely handicap its sufferers, there

has been a great interest in the relationship of this disorder and

intelligence. Interest in the association of intelligence and

schizophrenia has been widespread partly stems from the perceived

connection between schizophrenia and creativity, and posthumous research of famous intellectuals that have been insinuated to have suffered from the illness. Hollywood played a pivotal role popularizing the myth of the schizophrenic genius with the movie A Beautiful Mind that depicted the life story of Nobel Laureate, John Nash and his struggle with the illness.

Although stories of extremely bright schizophrenic individuals

such as that of John Nash do exist, they are the outliers and not the

norm. Studies analyzing the association between schizophrenia and

intelligence overwhelmingly suggest that schizophrenia is linked to

lower intelligence and decreased cognitive functioning. Since the manifestation of schizophrenia is partly characterized by cognitive and motor declines, current research focuses on understanding premorbid IQ patterns of schizophrenia patients.

In the most comprehensive meta-analysis published since the groundbreaking study by Aylward et al. in 1984, researchers at Harvard University found a medium-sized deficit in global cognition prior to the onset of schizophrenia. The mean premorbid IQ estimate for schizophrenia samples was 94.7 or 0.35 standard deviations below the mean,

and thus at the lower end of the average IQ range. Additionally, all

studies containing reliable premorbid and post-onset IQ estimates of

schizophrenia patients found significant decline in IQ scores when

comparing premorbid IQ to post-onset IQ. However, while the decline in IQ over the course of the onset of schizophrenia is consistent with theory,

some alternative explanations for this decline suggested by the

researchers include the clinical state of the patients and/or side

effects of antipsychotic medications.

A recent study published in March 2015 edition of the American Journal of Psychiatry

suggests that not only there is no correlation between high IQ and

schizophrenia, but rather that a high IQ may be protective against the

illness. Researchers from the Virginia Commonwealth University

analyzed IQ data from over 1.2 million Swedish males born between 1951

and 1975 at ages 18 to 20 years old to investigate future risk of

schizophrenia as a function of IQ scores. The researchers created stratified models using pairs of relatives to adjust for family clusters and later applied regression models to examine the interaction between IQ and genetic predisposition to schizophrenia. Results from the study suggest that subjects with low IQ were more sensitive to the effect of genetic liability

to schizophrenia than those with high IQ and that the relationship

between IQ and schizophrenia is not a consequence of shared genetic or

familial-environmental risk factors, but may instead be causal.

Post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic exposure

The Archive of General Psychiatry published a longitudinal study

of a randomly selected sample of 713 study participants (336 boys and

377 girls), from both urban and suburban settings. Of that group, nearly

76 percent had suffered through at least one traumatic event.

Those participants were assessed at age 6 years and followed up to age

17 years. In that group of children, those with an IQ above 115 were

significantly less likely to have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as a

result of the trauma, less likely to display behavioral problems, and

less likely to experience a trauma. The low incidence of Post-Traumatic

Stress Disorder among children with higher IQs was true even if the

child grew up in an urban environment (where trauma averaged three times

the rate of the suburb), or had behavioral problems.

Other disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorder, severe depression, and schizophrenia are less prevalent in higher IQ bands. Some studies have found that higher IQ persons show a higher prevalence of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, but a 2017 meta study found the opposite, that people who suffered from OCD had slightly lower average IQs.

Substance abuse

Substance abuse is a patterned use of drug consumption

in which a person uses substances in amounts or with methods that are

harmful to themselves or to others. Substance abuse is commonly

associated with a range of maladaptive behaviors

that are both detrimental to the individual and to society. Given the

terrible consequences that can transpire from abusing substances, recreational experimentation and/or recurrent use of drugs

are traditionally thought to be most prevalent among marginalized

strands of society. Nevertheless, the very opposite is true; research

both in national and individual levels have found that the relationship

between IQ and substance abuse indicates positive correlations between

superior intelligence, higher alcohol consumption and drug consumption.

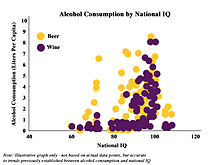

Note:

Illustrative graph only – not based on actual data points, but accurate

to trends previously established between alcohol consumption and

national IQ. For actual data points please refer to Belasen and Hafer

2013 publication.

A significant positive association between worldwide national alcohol consumption per capita and country level IQ scores has been found.

The relationship between childhood IQ scores and illegal drugs use by adolescence and middle age has been found. High IQ scores at age 10 are positively associated with intake of cannabis, cocaine (only after 30 years of age), ecstasy, amphetamine and polydrug and also highlight a stronger association between high IQ and drug use for women than men. Additionally, these findings are independent of socio-economic status or psychological distress during formative years. A high IQ at age 11 was predictive of increased alcohol dependency

later in life and a one standard deviation increase in IQ scores

(15-points) was associated with a higher risk of illegal drug use.

The counterintuitive nature of the correlation between high IQ

and substance abuse has sparked a fervent debate in the scientific

community with some researchers attributing these findings to IQ being

an inadequate proxy of intelligence, while others fault employed research methodologies and unrepresentative data.

However, with the increased number of studies publishing similar

results, overwhelming consensus is that the association between high IQ

and substance abuse is real, statistically significant and independent

of other variables.

There are several competing theories trying to make sense of this

apparent paradox. Doctor James White postulates that people with higher

IQs are more critical of information and thus less likely to accept

facts at face value. While marketing campaigns against drugs may deter

individuals with lower IQs from using drugs with disjoint arguments or

over-exaggeration of negative consequences, people with a higher IQ will

seek to verify the validity of such claims in their immediate

environment. White also eludes to an often-overlooked problem of people

with higher IQ, the lack of adequate challenges and intellectual stimulation.

White posits that high IQ individuals that are not sufficiently engaged

in their lives may choose to forgo good judgment for the sake of

stimulation.

The most prominent

theory attempting to explain the positive relationship between IQ and

substance abuse; however, is the Savanna–IQ interaction hypothesis by social psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa. The theory is founded on the assumption that intelligence is a domain-specific adaptation that has evolved as humans moved away from the birthplace of human race, the savanna. Therefore, theory follows that as humans explored beyond the savannas, intelligence rather than instinct dictated survival. Natural selection

privileged those who possessed high IQ while simultaneously favoring

those with an appetite for evolutionary novel behaviors and experiences.

For Kanazawa, this drive to seek evolutionary novel activities and

sensations translates to being more open and callous about experimenting

with and/or abusing substances in modern culture. For all the attention

that the Savanna–IQ interaction hypothesis has garnered with the

general public,

this theory however, receives equal amounts of praise and criticism in

the academic community with key pain points being the fact that humans

have continued to evolve after moving away from the savannas and Kanazawa's misattribution of aspects of the openness personality trait to being indicative of superior general intelligence.

Dementia

A decrease in IQ has also been shown as an early predictor of late-onset Alzheimer's Disease and other forms of dementia.

In a 2004 study, Cervilla and colleagues showed that tests of

cognitive ability provide useful predictive information up to a decade

before the onset of dementia.

However, when diagnosing individuals with a higher level of cognitive ability, a study of those with IQ's of 120 or more,

patients should not be diagnosed from the standard norm but from an

adjusted high-IQ norm that measured changes against the individual's

higher ability level.

In 2000, Whalley and colleagues published a paper in the journal Neurology,

which examined links between childhood mental ability and late-onset

dementia. The study showed that mental ability scores were

significantly lower in children who eventually developed late-onset

dementia when compared with other children tested.

Alcohol

The

relationship between alcohol consumption and intelligence is not

straightforward. In some cohorts higher intelligence has been linked to a

reduced risk of binge drinking. In one Scottish study higher

intelligence was linked to a lower chance of binge drinking; however,

units of alcohol consumed were not measured and alcohol induced

hangovers in middle age were used as a proxy for binge drinking.

Several studies have found the opposite effect with individuals of

higher intelligence being more likely to drink more frequently, consume

more units and have a higher risk of developing a drinking problem,

especially in women.

Drugs

In U.S. study the link between drug intake and intelligence suggests that individuals with lower IQ take more drugs. However, in the UK the opposite relationship has been found with higher intelligence being related to greater illegal drug use.

Smoking

The

relationship between intelligence and smoking has changed along with

public and government attitudes towards smoking. For people born in 1921

there was no correlation between intelligence and having smoked or not

smoked; however, there was a relationship between higher intelligence

and quitting smoking by adulthood. In another British study, high childhood IQ was shown to inversely correlate with the chances of starting smoking.

Diet

One British study found that high childhood IQ was shown to correlate with one's chance of becoming a vegetarian in adulthood.

Those of higher intelligence are also more likely to eat a healthier

diet including more fruit and vegetables, fish, poultry and wholemeal

bread and to eat less fried food.

Exercise

Higher

intelligence has been linked to exercising. More intelligent children

tend to exercise more as adults and to exercise vigorously.

A study of 11,282 individuals in Scotland who took intelligence

tests at ages 7, 9 and 11 in the 1950s and 1960s, found an "inverse

linear association" between childhood intelligence and hospital

admissions for injuries in adulthood. The association between childhood

IQ and the risk of later injury remained even after accounting for

factors such as the child's socioeconomic background.

Socioeconomic status

Practically all indicators of physical health and mental competence favour people of higher socioeconomic status (SES). Social class attainment is important because it can predict health across the lifespan, where people from lower social class have higher morbidity and mortality. SES and health outcomes are general across time, place, disease, and are finely graded up the SES continuum. Gottfredson argues that general intelligence (g) is the fundamental cause for health inequality.

The argument is that g is the fundamental cause of social class

inequality in health, because it meets six criteria that every candidate

for the cause must meet: stable distribution over time, is replicable,

is a transportable form of influence, has a general effect on health, is

measurable, and is falsifiable.

Stability: Any casual agent has to be persistent and stable

across time for its pattern of effects to be general over ages and

decades. Large and stable individual differences in g are developed by adolescence and the dispersion of g in population's intelligence present in every generation,

no matter what social circumstances are present. Therefore, equalizing

socioeconomic environments does very little to reduce the dispersion in

IQ. The dispersion of IQ in a society in general is more stable, than its dispersion of socioeconomic status.

Replicability: Siblings who vary in IQ also vary in socioeconomic success which can be comparable with strangers of comparable IQ. Also, g theory predicts that if genetic g is the principal mechanism carrying socioeconomic inequality between generations, then the maximum correlation between the parent and child SES will be near to their genetic correlation for IQ (.50).

Transportability: The performance and functional literacy

studies both illustrated how g is transportable across life situations

and it represents a set of largely generalizable reasoning and

problem-solving skills. G appear to be linearly linked to performance in school, jobs and achievements.

Generality: Studies show that IQ measured at the age of 11 predicted longevity, premature death, lung and stomach cancers, dementia,

loss of functional independence, more than 60 years later. Research

has shown that higher IQ at age 11 is significantly related to higher

social class in midlife. Therefore, it is safe to assume that higher SES, as well as higher IQ, generally predicts better health.

Measurability: g factor can be extracted from any broad set of

mental tests and has provided a common, reliable source for measuring

general intelligence in any population.

Falsifiability: theoretically, if g theory

would conceive health self-care as a job, as a set of instrumental

tasks performed by the individuals, it could predict g to influence the

health performance in the same way as it predicts performance in

education and job.

Chronic illnesses are the major illnesses in developed countries today, and their major risk factors are health habits and lifestyle. The higher social strata

knows the most and the lower social strata knows the least, whether

class is assessed by education, occupation or income and even when the

information seems to be most useful for the poorest. Higher g promotes

more learning, and it increases exposure to learning opportunities. So,

the problem is not in the lack of access to health-care, but the

patient's failure to use it effectively when delivered. Low literacy

has been associated with low use of preventive care, poor comprehension

of one's illness – even when care is free. Health self-management is

important because literacy provides the ability to acquire new

information and complete complex tasks and that limited problem solving

abilities make low-literacy patients less likely to change their

behaviour on the basis of new information. Chronic lack of good judgement and effective reasoning leads to chronically poor self-management.

Explanations of the correlation between intelligence and health

There

have been many reasons posited for the links between health and

intelligence. Although some have argued that the direction is one in

which health has an influence on intelligence, most have focused on the

influence of intelligence on health. Although health may definitely

affect intelligence, most of the cognitive epidemiological studies have

looked at intelligence in childhood when ill health is far less frequent

and a more unlikely cause of poor intelligence. Thus most explanations have focused on the effects intelligence has on health through its influence on mediating causes.

Various explanations for these findings have been proposed:

"First, ...intelligence is associated with more education, and thereafter with more professional occupations

that might place the person in healthier environments. ...Second, people with higher intelligence might engage in more healthy behaviours. ...Third, mental test scores from early life might act as a record of insults to the brain that have occurred before that date. ...Fourth, mental test scores obtained in youth might be an indicator of a well-put-together system. It is hypothesized that a well-wired body is more able to respond effectively to environmental insults..."

System integrity hypothesis vs evolution hypothesis

The

System integrity hypothesis posits that childhood intelligence is just

one aspect of a well wired and well-functioning body and suggests that

there is a latent trait that encompasses intelligence, health and many

other factors.

This trait indexes how well the body is functioning and how well the

body can respond to change and return to a normal balance again

(allostatic load). According to the system integrity hypothesis lower IQ

does not cause mortality but instead poor system integrity causes lower

intelligence and poorer health as well as a range of other traits which

can be thought of as markers of system integrity. Professor Ian Deary

has proposed that fluctuating asymmetry, speed of information

processing, physical co-ordination, physical strength, metabolic

syndrome and genetic correlation may be further potential markers of

system integrity which by definition should explain a large part of or

nullify the relationship between intelligence and mortality.

An opposing theory to the system integrity theory is the

evolutionary novelty theory which suggests that those with higher

intelligence are better equipped to deal with evolutionary novel events.

It is proposed that intelligence evolved to tackle evolutionarily novel

situations and that those with a higher IQ are better able to process

when such a novel situation is dangerous or a health hazard and thus are

likely to be in better health. This theory provides a theoretical

background for evidence found that supports the idea that intelligence

is related to mortality through health behaviours such as wearing a

seatbelt or quitting smoking.

Evolutionary novelty theory emphasises the role of behaviour in the link

between mortality and intelligence whereas system integrity emphasis

the role of genes. Thus system integrity predicts that individuals of

higher intelligence will be better protected from diseases that are

caused primarily by genetics whereas evolutionary adaptive theory

suggests that individuals of higher intelligence will be better

protected from diseases that are less heritable and are caused by poor

life choices. One study which tested this idea looked at the incidence

of heritable and non-heritable cancers in individuals of differing

levels of intelligence. They found that those of higher intelligence

were less likely to suffer from cancer that was not heritable, that was

based on lifestyle, thus supporting the evolutionary novelty theory.

However this was only a preliminary study and only included the disease

cancer, which has been found in previous studies to have an ambiguous

relationship with intelligence.

Disease and injury prevention

Having

higher intelligence scores may mean that individuals are better at

preventing disease and injury. Their cognitive abilities may equip them

with a better propensity for understanding the injury and health risks

of certain behaviours and actions.

Fatal and non-fatal accidental injury have been associated with lower

intelligence.

This may be because individuals of higher intelligence are more likely

to take precautions such as wearing seat belts, helmets etc. as they are

aware of the risks.

Further there is evidence that more intelligent people behave in a healthier way.

People with higher IQ test scores tend to be less likely to smoke or drink alcohol heavily. They also eat better diets, and they are more physically active. So they have a range of better behaviours that may partly explain their lower mortality risk.

— -Dr. David Batty

Individuals with higher cognitive abilities are also better equipped

for dealing with stress, a factor that has been implemented in many

health problems ranging from anxiety to cardiovascular disease. It has

been suggested that higher intelligence leads to a better sense of

control over one's own life and a reduction in feelings of stress.

One study found that individuals with lower intelligence experienced a

greater number of functional somatic symptoms, symptoms that cannot be

explained by organic pathology and are thought to be stress related.

However most of the relationship was mediated by work conditions.

Disease and injury management

There

is evidence that higher intelligence is related to better self-care

when one has an illness or injury. One study asked participants to take

aspirin or a placebo on a daily basis during a study on cardiovascular

health. Participants with higher intelligence persisted with taking the

medication for longer than those with lower intelligence indicating

that they could care for themselves better.

Studies have shown that individuals with lower intelligence have lower

health literacy and a study looking at the link between health literacy

and actual health found that it was mediated almost entirely by

intelligence.

It has been claimed that up to a third of medications are not taken

correctly and thus jeopardize the patients' health. This is particularly

relevant for those with heart problems as the misuse of some heart

medications can actually double the risk of death.

More intelligent individuals also make use of preventative healthcare

more often for example visiting the doctors. Some have argued however

that this is an artefact of higher SES; that those with lower

intelligence tend to be from a lower social class and have less access

to medical facilities. However it has been found that even when access

to healthcare is equal, those with lower intelligence still make less

use of the services.

Psychiatric illness

A

diagnosis of any mental illness, even mild psychological distress, is

linked to an increased risk of illness and premature death. The majority

of psychiatric illness' are also linked to lower intelligence.

Thus it has been proposed that psychiatric morbidity may be another

pathway through which intelligence and mortality are related.

Despite this the direction of causation between Intelligence and mental

health issues has been disputed. Some argue that mental health issues

such as depression and schizophrenia may cause a decline in mental

functioning and thus scores on intelligence tests whilst others believe

that it is lower intelligence that effects likelihood of developing a

mental health issue.

Although evidence for both points of view has been found, most of the

cognitive epidemiological studies are carried out using intelligence

scores from childhood, when the psychiatric condition was not present,

ensuring that it was not the condition which caused the lower scores.

This link has been shown to explain part of the relationship between

childhood intelligence and mortality, however the amount of variance

explained varies from less than 10 percent to about 5 percent.

Socioeconomic position in adulthood

Although

childhood economic status may be seen as a confounder in the

relationship between intelligence and mortality, as it is likely to

affect intelligence, it is likely that adult SES mediates the

relationship. The idea is that intelligent children will find themselves

getting a better education, better jobs and will settle in a safer and

healthier environment. They will have better access to health resources,

good nutrition and will be less likely to experience the hazards and

health risks associated with living in poorer neighbourhoods. Several

studies have found that there is an association between adult SES and

mortality.

Proposed general fitness factor of both cognitive ability and health, the f-factor

Because of the above-mentioned findings, some researchers have proposed a general factor of fitness analogous to the g-factor

for general mental ability/intelligence. This factor is supposed to

combine fertility factors, health factors, and the g-factor. For

instance, one study found a small but significant correlation between

three measures of sperm quality and intelligence.