A catt of the Bakhtiari people, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province, Iran.

Livestock market in Mali.

Pastoralism is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horses and sheep.

"Pastoralism" often has a mobile aspect but this can take many

forms and be at different scales. Sedentary pastoralism is becoming more

common as the hardening of political borders, expansion of crop

agriculture, and building of fences reduces ability to move. Mobile

pastoralism includes moving herds distances in search of fresh pasture

and water, something that can occur daily or even within a few hours,

to transhumance, where animals are moved seasonally, to nomadism, where

pastoralists and families move with the animals year-round. In sedentary

pastoralism, or pastoral farming, pastoralists grow crops and improve

pastures for their livestock. One example is a savanna area where

pastoralists and their animals gather when rainwater is abundant and the

pasture is rich, then scatter during the drying of the savanna. Another is the movement of livestock from summer pastures in

lowlands, to montane pastures in the summer where grass is green and

plentiful during the dry season. Grazing in woodlands and forests may be referred to as silvopastoralism.

Pastoralist herds interact with their environment, and mediate

human relations with the environment as a way of turning uncultivated

plants like wild grass into consumable, high quality, food. In many

places, grazing herds on savannas and woodlands can help maintain the

biodiversity of the savannas and prevent them from evolving into dense

shrublands or forests. Grazing and browsing at the appropriate levels

often can increase biodiversity in Mediterranean climate regions. Pastoralists may also use fire to make ecosystems more suitable for grazing and browsing animals. For instance, the Turkana people of northwest Kenya

use fire to prevent the invasion of the savanna by woody plant species.

Biomass of the domesticated and wild animals was increased by a higher

quality of grass.

Pastoralism is found in many variations throughout the world,

generally where enviornmental charactersitics such as aridity, poor

soils, cold or hot temperature, and lack of water make crop growing

difficult or impossible. Pastoralism remains a way of life in Africa,

the Tibetan plateau, the Eurasian steppes,

the Andes, Patagonia, the Pampas, Australia, and other many other

places. Composition of herds, management practices, social organization

and all other aspects of pastoralism vary between areas and between

social groups. Many traditional practices have also had to adapt to the

changing circumstance of the modern world, including climatic conditions

affecting the availability of grasses and the loss of mobility over

large landscapes. Ranches of the United States and sheep stations and cattle stations of Australia are seen by some as modern variations.

Origins

Khoikhoi dismantling their huts, preparing to move to new pastures. Aquatint by Samuel Daniell (1805). The Khoikhoi practiced pastoralism for thousands of years in southern Africa.

One theory is that pastoralism was created from mixed farming. Bates and Lees proposed that it was the incorporation of irrigation into farming which ensued in specialization.

Advantages of mixed farming include reducing risk of failure, spreading

labour, and re-utilizing resources. The importance of these advantages

and disadvantages to different farmers differs according to the

sociocultural preferences of the farmers and the biophysical conditions

as determined by rainfall, radiation, soil type, and disease.

The increased productivity of irrigation agriculture led to an

increase in population and an added impact on resources. Bordering areas

of land remained in use for animal breeding. This meant that large

distances had to be covered by herds to collect sufficient forage.

Specialization occurred as a result of the increasing importance of both

intensive agriculture and pastoralism. Both agriculture and pastoralism

developed alongside each other, with continuous interactions.

There is another theory that suggests pastoralism evolved from hunting and gathering.

Hunters of wild goats and sheep were knowledgeable about herd mobility

and the needs of the animals. Such hunters were mobile and followed the

herds on their seasonal rounds. Undomesticated herds were chosen to

become more controllable for the proto-pastoralist nomadic hunter and

gatherer groups by taming and domesticating

them. Hunter-gatherers' strategies in the past have been very diverse

and contingent upon the local environment conditions, like those of

mixed farmers. Foraging strategies have included hunting or trapping big game and smaller animals, fishing, collecting shellfish or insects, and gathering wild plant foods such as fruits, seeds, and nuts.

These diverse strategies for survival amongst the migratory herds could

also provide an evolutionary route towards nomadic pastoralism.

Resources

Pastoralism

occurs in uncultivated areas. Wild animals eat the forage from the

marginal lands and humans survive from milk, blood, and often meat of

the herds and often trade by-products like wool and milk for money and food.

Pastoralists do not exist at basic subsistence.

Pastoralists often compile wealth and participate in international

trade. Pastoralists have trade relations with agriculturalists, horticulturalists,

and other groups. Pastoralists are not extensively dependent on milk,

blood, and meat of their herd. McCabe noted that when common property

institutions are created, in long-lived communities, resource

sustainability is much higher, which is evident in the East African grasslands of pastoralist populations.

However, it needs to be noted that the property rights structure is

only one of the many different parameters that affect the sustainability

of resources, and common or private property per se, does not

necessarily lead to sustainability.

Some pastoralists supplement herding with hunting and gathering, fishing and/or small-scale farming or pastoral farming.

Mobility

Mongol pastoralist in the Khövsgöl Province

Mobility allows pastoralists to adapt to the environment, which opens

up the possibility for both fertile and infertile regions to support

human existence. Important components of pastoralism include low

population density, mobility, vitality, and intricate information

systems. The system is transformed to fit the environment rather than

adjusting the environment to support the "food production system." Mobile pastoralists can often cover a radius of a hundred to five hundred kilometers.

Pastoralists and their livestock have impacted the environment.

Lands long used for pastoralism have transformed under the forces of

grazing livestock and anthropogenic fire.

Fire was a method of revitalizing pastureland and preventing forest

regrowth. The collective environmental weights of fire and livestock

browsing have transformed landscapes in many parts of the world. Fire

has permitted pastoralists to tend the land for their livestock.

Political boundaries are based on environmental boundaries. The Maquis shrublands of the Mediterranean region are dominated by pyrophytic plants that thrive under conditions of anthropogenic fire and livestock grazing.

Nomadic pastoralists

have a global food-producing strategy depending on the management of

herd animals for meat, skin, wool, milk, blood, manure, and transport.

Nomadic pastoralism is practiced in different climates and environments

with daily movement and seasonal migration. Pastoralists are among the

most flexible populations. Pastoralist societies have had field armed

men protect their livestock and their people and then to return into a

disorganized pattern of foraging. The products of the herd animals are

the most important resources, although the use of other resources,

including domesticated and wild plants, hunted animals, and goods

accessible in a market economy are not excluded. The boundaries between

states impact the viability of subsistence and trade relations with

cultivators.

Pastoralist strategies typify effective adaptation to the environment.

Precipitation differences are evaluated by pastoralists. In East

Africa, different animals are taken to specific regions throughout the

year that corresponds to the seasonal patterns of precipitation. Transhumance is the seasonal migration of livestock and pastoralists between higher and lower pastures.

Some pastoralists are constantly moving, which may put them at

odds with sedentary people of towns and cities. The resulting conflicts

can result in war for disputed lands. These disputes are recorded in

ancient times in the Middle East, as well as for East Asia. Other pastoralists are able to remain in the same location which results in longer-standing housing.

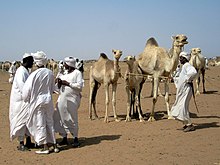

Camel market in Sudan

Different mobility patterns can be observed: Somali

pastoralists keep their animals in one of the harshest environments but

they have evolved of the centuries. Somalis have well developed

pastoral culture where complete system of life and governance has been

refined. Somali poetry

depicts humans interactions, pastoral animals, beasts on the prowl, and

other natural things such the rain, celestial events and historic

events of significance.

Mobility was an important strategy for the Ariaal;

however with the loss of grazing land impacted by the growth in

population, severe drought, the expansion of agriculture, and the

expansion of commercial ranches and game parks, mobility was lost. The

poorest families were driven out of pastoralism and into towns to take

jobs. Few Ariaal families benefited from education, healthcare, and income earning.

The flexibility of pastoralists to respond to environmental

change was reduced by colonization. For example, mobility was limited in

the Sahel region of Africa with settlement being encouraged. The

population tripled and sanitation and medical treatment were improved.

The Afar pastoralists in Ethiopia uses an indigenous communication method called dagu

for information. This helps them in getting crucial information about

climate and availability of pastures at various locations.

Information

Pastoralists

have mental maps of the value of specific environments at different

times of year. Pastoralists have an understanding of ecological

processes and the environment. Information sharing is vital for creating knowledge through the networks of linked societies.

Pastoralists produce food in the world’s harshest environments,

and pastoral production supports the livelihoods of rural populations on

almost half of the world’s land. Several hundred million people are

pastoralists, mostly in Africa and Asia. ReliefWeb

reported that "Several hundred million people practice pastoralism—the

use of extensive grazing on rangelands for livestock production, in over

100 countries worldwide. The African Union estimated that Africa has

about 268 million pastoralists—over a quarter of the total

population—living on about 43 percent of the continent’s total land

mass." Pastoralists manage rangelands covering about a third of the Earth’s terrestrial surface and are able to produce food where crop production is not possible.

Nenets reindeer herders in Russia

Pastoralism has been shown, "based on a review of many studies, to be

between 2 and 10 times more productive per unit of land than the

capital intensive alternatives that have been put forward". However,

many of these benefits go unmeasured and are frequently squandered by

policies and investments that seek to replace pastoralism with more

capital intensive modes of production.

They have traditionally suffered from poor understanding,

marginalization and exclusion from dialogue. The Pastoralist Knowledge

Hub, managed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN serves

as a knowledge repository on technical excellence on pastoralism as well

as "a neutral forum for exchange and alliance building among

pastoralists and stakeholders working on pastoralist issues".

Pastoralism and farm animal genetic resource

There is a variation in genetic makeup of the farm animals driven mainly by natural and human based selection.

For example, pastoralists in large parts of Sub Saharan Africa are

preferring livestock breeds which are adapted to their environment and

able to tolerate drought and diseases. However in other animal production systems these breeds are discouraged and more productive exotic ones are favored. This situation could not be left unaddressed due to the changes in market preferences and climate all over the world,

which could lead to changes in livestock diseases occurrence and

decline forage quality and availability. Hence pastoralists are

conserving farm animal genetic through community based conservation

(CBC) of local livestock breeds.

Generally conserving farm animal genetic resources under pastoralism is

advantageous in terms of reliability and associated cost.

Tragedy of the commons

Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons (1968) described how common property resources, such as the land shared by pastoralists, eventually become overused and ruined. According to Hardin's paper, the pastoralist land use strategy suffered criticisms of being unstable and a cause of environmental degradation.

Tuareg pastoralists and their herds flee south into Nigeria from Niger during the 2005–06 Niger food crisis

However, one of Hardin's conditions for a "tragedy of the commons" is

that people can't communicate with each other or make agreements and

contracts. Many scholars have pointed out that this is ridiculous, and

yet it is applied in development projects around the globe, motivating

the destruction of community and other governance systems that have

managed sustainable pastoral systems for thousands of years. The

outcomes have often been disastrous.

Pastoralists in the Sahel zone in Africa were held responsible for the depletion of resources. The depletion of resources was actually triggered by a prior interference and punitive climate conditions.

Hardin's paper suggests a solution to the problems, offering a coherent

basis for privatization of land, which stimulates the transfer of land

from tribal peoples to the state or to individuals. The privatized programs impact the livelihood of the pastoralist societies while weakening the environment. Settlement programs often serve the needs of the state in reducing the autonomy and livelihoods of pastoral people.

The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia and other countries in the Sahel and Horn of Africa regions have been exacerbated by climate change, land degradation, and population growth.

However, recently it has been shown that pastoralism supports

human existence in harsh environments and often represents a sustainable

approach to land use.