From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

| Mission type | Multi-target orbiter |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2007-043A |

| Website | dawn |

| Mission duration | ~9 years[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Orbital Sciences · JPL · UCLA |

| BOL mass | 1,240 kg (2,730 lb) (wet)[2] |

| Power | 1300 W (Solar array) at 3 AU[2] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | September 27, 2007 11:34:00 UTC[3] (7 years, 5 months and 7 days ago) |

| Rocket | Delta II 7925H |

| Launch site | Space Launch Complex 17B Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, United States |

| Flyby of Mars (Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | February 4, 2009 (6 years, 1 month and 2 days ago) |

| Distance | 549 km (341 mi) |

| 4 Vesta orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | July 16, 2011 04:47 UTC[4] (3 years, 7 months and 18 days ago) |

| Departed orbit | September 5, 2012 (2 years, 6 months and 1 day ago) |

| Ceres orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | March 6, 2015[5] |

Dawn mission patch |

|

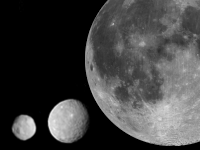

Dawn is a space probe launched by NASA in 2007 to study the two largest protoplanets of the asteroid belt: Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres.[6] Dawn entered orbit around Ceres on March 6, 2015,[7] but has been taking high-resolution images of Ceres since December 1, 2014.[8][5]

Dawn was the first spacecraft to visit Vesta, entering orbit on July 16, 2011, and successfully completed its 14-month Vesta survey mission in late 2012.[9][10] Dawn is the first spacecraft to visit Ceres and to orbit two separate extraterrestrial bodies.[7]

The mission is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, with major components contributed by European partners from the Netherlands, Italy and Germany. It is the first NASA exploratory mission to use ion propulsion to enter orbits; previous multi-target missions using conventional drives, such as the Voyager program, were restricted to flybys.[2]

Project history

Initial cancellations

The status of the Dawn mission changed several times. The project was cancelled in December 2003,[11] and then reinstated in February 2004. In October 2005, work on Dawn was placed in "stand down" mode, and in January 2006, the mission was discussed in the press as "indefinitely postponed", even though NASA had made no new announcements regarding its status.[12] On March 2, 2006, Dawn was again cancelled by NASA.[13]Reinstatement

The spacecraft's manufacturer, Orbital Sciences Corporation, appealed NASA's decision, offering to build the spacecraft at cost, forgoing any profit in order to gain experience in a new market field. NASA then put the cancellation under review,[14] and on March 27, 2006, it was announced that the mission would not be cancelled after all.[15][16] In the last week of September 2006, the Dawn mission's instrument payload integration reached full functionality. Although originally projected to cost US$373 million, cost overruns inflated the final cost of the mission to US$446 million in 2007.[17] The Dawn mission team is led by Christopher T. Russell.Scientific background

The Dawn mission was designed to study two large bodies in the asteroid belt in order to answer questions about the formation of the Solar System, as well as to test the feasibility of its ion drive. Ceres and Vesta were chosen as two contrasting protoplanets, the first one apparently "wet" (i.e. icy and cold) and the other "dry" (i.e. rocky), whose accretion was terminated by the formation of Jupiter. The two bodies provide a bridge in scientific understanding between the formation of rocky planets and the icy bodies of the Solar System, and under what conditions a rocky planet can hold water.[18]

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) adopted a new definition of planet on August 24, 2006, which introduced the term "dwarf planet" for ellipsoidal worlds that were too small to qualify for planetary status by "clearing their orbital neighborhood" of other orbiting matter. If it succeeds, Dawn will be the first mission to study a dwarf planet, arriving at Ceres a few months before the arrival of the New Horizons probe at Pluto in July 2015.

Ceres is a dwarf planet whose mass comprises about one-third of the total mass of the bodies in the asteroid belt, and whose spectral characteristics suggest a composition similar to that of a water-rich carbonaceous chondrite.[19] Vesta, a smaller, water-poor achondritic asteroid, has experienced significant heating and differentiation. It shows signs of a metallic core, a Mars-like density and lunar-like basaltic flows.[20]

Available evidence indicates that both bodies formed very early in the history of the Solar System, thereby retaining a record of events and processes from the time of the formation of the terrestrial planets. Radionuclide dating of pieces of meteorites thought to come from Vesta suggests that Vesta differentiated quickly, in three million years or less. Thermal evolution studies suggest that Ceres must have formed some time later, more than three million years after the formation of CAIs (the oldest known objects of Solar System origin).[20]

Moreover, Vesta appears to be the source of many smaller objects in the Solar System. Most (but not all) V-type near-Earth asteroids, and some outer main-belt asteroids, have spectra similar to Vesta, and are thus known as vestoids. Five percent of the meteoritic samples found on Earth, the howardite–eucrite–diogenite (HED) meteorites, are thought to be the result of a collision or collisions with Vesta.

In 2005, Peter Thomas of Cornell University proposed that Ceres has a differentiated interior;[21] its oblateness appears too small for an undifferentiated body, which indicates that it consists of a rocky core overlain with an icy mantle.[21] There is a large collection of potential samples from Vesta accessible to scientists, in the form of over 1,400 HED meteorites,[22] giving insight into Vestan geologic history and structure. Vesta is thought to consist of a metallic iron–nickel core, an overlying rocky olivine mantle and crust.[23][24][25]

Objectives

The Dawn mission's goal is to characterize the conditions and processes of the Solar System's earliest eon by investigating in detail two of the largest protoplanets remaining intact since their formation.[26] The primary question that the mission addresses is the role of size and water in determining the evolution of the planets.[26] Ceres and Vesta are highly suitable bodies with which to address this question, as they are two of the most massive of the protoplanets. Ceres is geologically very primitive and icy, while Vesta is evolved and rocky. Their contrasting characteristics are thought to have resulted from them forming in two different regions of the early Solar System.[26]

There are three principal scientific drivers for the mission. First, the Dawn mission can capture the earliest moments in the origin of the Solar System, granting an insight into the conditions under which these objects formed. Second, Dawn determines the nature of the building blocks from which the terrestrial planets formed, improving scientific understanding of this formation. Finally, it contrasts the formation and evolution of two small planets that followed very different evolutionary paths, allowing scientists to determine what factors control that evolution.[26]

Specifications

Dimensions

With its solar array in the retracted launch position, the Dawn spacecraft is 2.36 meters (7.7 ft) long. With its solar arrays fully extended, Dawn is 19.7 meters (65 ft) long.[27] Total area of solar arrays is 36.4 square metres (392 sq ft).[28]Propulsion system

The Dawn spacecraft is propelled by three xenon ion thrusters that inherited NSTAR engineering technology from the Deep Space 1 spacecraft.[29] They have a specific impulse of 3,100 s and produce a thrust of 90 mN.[30] The whole spacecraft, including the ion propulsion thrusters, is powered by a 10 kW (at 1 au) triple-junction gallium arsenide photovoltaic solar array manufactured by Dutch Space.[31][32] To get to Vesta, Dawn was allocated 275 kg (606 lb) of xenon, with another 110 kg (243 lb) to reach Ceres,[33] out of a total capacity of 425 kg (937 pounds) of on-board propellant.[34] With the propellant it carries, Dawn can perform a velocity change of more than 10 km/s over the course of its mission, far more than any previous spacecraft achieved with onboard propellant after separation from its launch rocket.[33] Dawn is NASA's first purely exploratory mission to use ion propulsion engines.[35] The spacecraft also has twelve 0.9N hydrazine thrusters for attitude control, which can assist in orbital insertion.[36]

Microchip

Dawn carries a memory chip bearing the names of more than 360,000 space enthusiasts.[37] The names were submitted online as part of a public outreach effort between September 2005 and November 4, 2006.[38] The microchip, which is about the size of a United States nickel coin, was installed on May 17, 2007, above the spacecraft's forward ion thruster, underneath its high-gain antenna.[39] More than one microchip was made, with a back-up copy put on display at the 2007 Open House event at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.Payload

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory provided overall planning and management of the mission, the flight system and scientific payload development, and provided the Ion Propulsion System. Orbital Sciences Corporation provided the spacecraft, which constituted the company's first interplanetary mission. The Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) provided the framing cameras, the Italian Space Agency provided the mapping spectrometer, and the Los Alamos National Laboratory provided the gamma ray and neutron spectrometer.[2]

- Framing camera (FC) — The framing camera uses 20 mm aperture, f/7.9 refractive optical system with a focal length of 150 mm.[40][41] A frame-transfer charge-coupled device (CCD), a Thomson TH7888A,[41] at the focal plane has 1024 × 1024 sensitive 93-μrad pixels, yielding a 5.5° x 5.5° field of view. An 8-position filter wheel permits panchromatic (clear filter) and spectrally selective imaging (7 narrow band filters). The broadest filter allows imaging at wavelengths ranging from 400 to 1050 nm. In addition, the framing camera will acquire images for optical navigation while in the vicinities of Vesta and Ceres. The FC computer is a custom radiation-hardened Xilinx system with a LEON2 core and 8 GiB of memory.[41] The camera will offer resolutions of 17 m/pixel for Vesta and 66 m/pixel for Ceres.[41] Because the framing camera is vital for both science and navigation, the payload has two identical and physically separate cameras (FC1 & FC2) for redundancy, each with its own optics, electronics, and structure.[2][42]

- Visible and infrared spectrometer (VIR) — This instrument is a modification of the visible and infrared thermal-imaging spectrometer used on the Rosetta and Venus Express spacecraft. It also draws its heritage from the Saturn orbiter Cassini's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer. The spectrometer's VIR spectral frames are 256 (spatial) × 432 (spectral), and the slit length is 64 mrad. The mapping spectrometer incorporates two channels, both fed by a single grating. A CCD yields frames from 0.25 to 1.0 μm, while an array of HgCdTe photodiodes cooled to about 70K spans the spectrum from 0.95 to 5.0 μm.[2][43]

- Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRaND) — This instrument is based on similar instruments flown on the Lunar Prospector and Mars Odyssey space missions. This instrument includes 21 sensors with a very wide field of view.[40] It will be used to measure the abundances of the major rock-forming elements (oxygen, magnesium, aluminium, silicon, calcium, titanium, and iron) on Vesta and Ceres, as well as potassium, thorium, uranium, and water (inferred from hydrogen content).[44][45][46][47][48][49]

Mission summary

Launch preparations

On April 10, 2007, the spacecraft arrived at the Astrotech Space Operations subsidiary of SPACEHAB, Inc. in Titusville, Florida, where it was prepared for launch.[51][52] The launch was originally scheduled for June 20, but was delayed until June 30 due to delays with part deliveries.[53] A broken crane at the launch pad, used to raise the solid rocket boosters, further delayed the launch for a week, until July 7; prior to this, on June 15, the second stage was successfully hoisted into position.[54] A mishap at the Astrotech Space Operations facility, involving slight damage to one of the solar arrays, did not have an effect on the launch date; however, bad weather caused the launch to slip to July 8. Range tracking problems then delayed the launch to July 9, and then July 15. Launch planning was then suspended in order to avoid conflicts with the Phoenix mission to Mars, which was successfully launched on August 4.Launch

Dawn launching on a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 17 on September 27, 2007.

The launch of Dawn was rescheduled for September 26, 2007,[55][56][57] then September 27, due to bad weather delaying fueling of the second stage, the same problem that delayed the July 7 launch attempt. The launch window extended from 07:20–07:49 EDT (11:20–11:49 GMT).[58] During the final built-in hold at T−4 minutes, a ship entered the exclusion area offshore, the strip of ocean where the rocket boosters were likely to fall after separation. After commanding the ship to leave the area, the launch was required to wait for the end of a collision avoidance window with the International Space Station.[59] Dawn finally launched from pad 17-B at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on a Delta 7925-H rocket[60] at 07:34 EDT,[61][62][63] reaching escape velocity with the help of a spin-stabilized solid-fueled third stage.[64][65] Thereafter, Dawn's ion thrusters took over.

Transit (Earth to Vesta)

After initial checkout, during which the ion thrusters accumulated more than 11 days of thrust, Dawn began long-term cruise propulsion on December 17, 2007.[66] On October 31, 2008, Dawn completed its first thrusting phase to send it on to Mars for a gravity assist flyby in February 2009. During this first interplanetary cruise phase, Dawn spent 270 days, or 85% of this phase, using its thrusters. It expended less than 72 kilograms of xenon propellant for a total change in velocity of 1.81 kilometers per second. On November 20, 2008, Dawn performed its first trajectory correction maneuver (TCM1), firing its number 1 thruster for 2 hours, 11 minutes.Dawn made its closest approach (549 km) to Mars on February 17, 2009 during a successful gravity assist.[67][68] On this day, the spacecraft placed itself in safe mode, resulting in some data acquisition loss. The spacecraft was reported to be back in full operation two days later, with no impact on the subsequent mission identified. The root cause of the event was reported to be a software programming error.[69]

To cruise from Earth to its targets, Dawn traveled in an elongated outward spiral trajectory. NASA posts and continually updates the current location and status of Dawn online.[70] The actual Vesta chronology and estimated Ceres chronology are as follows:[1]

- September 27, 2007: launch

- February 17, 2009: Mars gravity assist

- July 16, 2011: Vesta arrival and capture

- August 11–31, 2011: Vesta survey orbit

- September 29, 2011–November 2, 2011: Vesta first high altitude orbit

- December 12, 2011–May 1, 2012: Vesta low altitude orbit

- June 15, 2012–July 25, 2012: Vesta second high altitude orbit

- September 5, 2012: Vesta departure

- March 6, 2015: Ceres arrival

- Early 2016: End of primary Ceres operations

Vesta approach

As Dawn approached Vesta, the Framing Camera instrument took progressively higher-resolution images, which were published online and at news conferences by NASA and MPI.Dawn was scheduled to be inserted into orbit at 05:00 UTC on July 16 after a period of thrusting with its ion engines. Because its antenna was pointed away from the Earth during thrusting, scientists were not able to immediately confirm whether or not Dawn successfully made the maneuver. The spacecraft would then reorient itself, and was scheduled to check in at 06:30 UTC on July 17.[74] NASA later confirmed that it received telemetry from Dawn indicating that the spacecraft successfully entered orbit around Vesta.[75] The exact time of insertion could not be confirmed, since it depended on Vesta's mass distribution, which was not precisely known and at that time had only been estimated.[76]

Vesta orbit

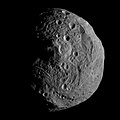

After being captured by Vesta's gravity and entering its orbit on July 16, 2011,[77] Dawn moved to a lower, closer orbit by running its xenon-ion engine using solar power. On August 2, it paused its spiralling approach to enter a 69-hour survey orbit at an altitude of 2,750 km. It assumed a 12.3-hour high-altitude mapping orbit at 680 km on September 27, and finally entered a 4.3-hour low-altitude mapping orbit at 210 km on December 8.[78][79][80]Dawn was originally scheduled to depart Vesta and begin its two and a half year journey to Ceres on August 26, 2012.[10] However, a problem with one of the spacecraft's reaction wheels forced Dawn to delay its departure from Vesta's gravity until September 5, 2012.[9][88][89][90][91]

-

The snowman shaped craters on Vesta

Results

| Geologic Map of Vesta.[92] |

|---|

The most ancient and heavily cratered regions are brown; areas modified by the Veneneia and Rheasilvia impacts are purple (the Saturnalia Fossae Formation, in the north)[93] and light cyan (the Divalia Fossae Formation, equatorial),[92] respectively; the Rheasilvia impact basin interior (in the south) is dark blue, and neighboring areas of Rheasilvia ejecta (including an area within Veneneia) are light purple-blue;[94][95] areas modified by more recent impacts or mass wasting are yellow/orange or green, respectively.

|

Transit (Vesta to Ceres)

During its time in orbit around Vesta the probe experienced failures of reaction wheels. Investigators will modify their activities upon arrival at Ceres for close range geographical survey mapping. The Dawn team will orient the probe by what they have stated is a "hybrid" mode. This mode will utilize both reaction wheels and ion thrusters. Engineers have determined that the hybrid mode will conserve fuel. On November 13, 2013, during the transit, in a test preparation, Dawn engineers completed a 27-hour-long series of exercises of said hybrid mode.[96]On September 11, 2014, Dawn's ion thrusting unexpectedly halted and the probe began operating in a triggered safe mode. To avoid a lapse in propulsion, the mission team hastily exchanged the active ion engine and electrical controller with another. The team stated that they had a plan in place to revive this disabled component later in 2014. The controller in the ion propulsion system may have been damaged by a high-energy particle of radiation. Upon exiting the safe mode on September 15, the probe resumed normal ion thrusting.[97]

Further, the Dawn investigators also found that they could not aim the main communications antenna towards Earth. Another antenna of weaker capacity was instead retasked. To correct the problem the probe's computer was reset and the aiming mechanism of the main antenna was restored.

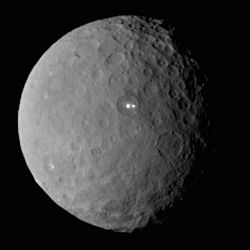

Ceres approach

Dawn began photographing an extended disk of Ceres on December 1, 2014,[8] with images of partial rotations on January 13 and 25, 2015 released as animations. Images taken from Dawn of Ceres after January 26 exceed the resolution of the Hubble Space Telescope,[98] while images taken of Pluto by New Horizons will exceed the resolution of the Hubble telescope by approximately May 5, 2015.[99]Progression of images of Ceres by Dawn between January and February 2015

Dawn entered Ceres orbit on March 6, 2015[5], four months prior to the arrival of New Horizons at Pluto; Dawn will thus be the first mission to study a dwarf planet at close range.[101][102]

| Date | distance (km) |

diameter (px) |

resolution (km/px) |

portion of disk illuminated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 1 | 1,200,000 | 9 | 112 | 94% |

| January 13 | 383,000 | 27 | 36 | 95% |

| January 25 | 237,000 | 43 | 22 | 96% |

| February 3 | 146,000 | 70 | 14 | 97% |

| February 12 | 83,000 | 122 | 7.8 | 98% |

| February 19 | 46,000 | 222 | 4.3 | 87% |

| February 25 | 40,000 | 255 | 3.7 | 44% |

| March 1 | 49,000 | 207 | 4.6 | 23% |

| April 10 | 33,000 | 306 | 3.1 | 17% |

| April 15 | 22,000 | 453 | 2.1 | 49% |