From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Wine | |

|---|---|

| Source plant(s) | Vitis vinifera, V. labrusca, V. aestivalis, V. ruprestris, V. rotundifolia and V. riparia' |

| Part(s) of plant | fruit |

| Geographic origin | Caucasus and Middle East |

| Active ingredients | ethanol |

| Main producers | France, Italy, Spain, United States, Argentina, Australia, China, Germany, South Africa, Portugal, Chile, Romania, Greece, Russia, Hungary |

| Legal status |

|

Wine is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented grapes or other fruits. The natural chemical balance of grapes lets them ferment without the addition of sugars, acids, enzymes, water, or other nutrients.[1] Yeast consumes the sugars in the grapes and converts them into ethanol and carbon dioxide. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts produce different styles of wine. The well-known variations result from the very complex interactions between the biochemical development of the fruit, reactions involved in fermentation, terroir and subsequent appellation, along with human intervention in the overall process.

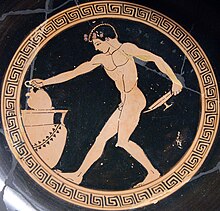

Wine has been produced for thousands of years, with the earliest wines being drunk c. 6000 BC in Georgia.[2][3][4] It had reached the Balkans by c. 4500 BC and was consumed and celebrated in ancient Greece and Rome. It has been consumed for its intoxicating effects throughout history and the psychoactive effects are evident at normal serving sizes.[5][6]

Wines made from produce besides grapes include rice wine, pomegranate wine, apple wine and elderberry wine and are generically called fruit wine.

Wine has played an important role in religion. Red wine was associated with blood by the ancient Egyptians[7] and was used by both the Greek cult of Dionysus and the Romans in their Bacchanalia; Judaism also incorporates it in the Kiddush and Christianity in the Eucharist.

Etymology

The English word "wine" comes from the Proto-Germanic *winam, an early borrowing from the Latin vinum, "wine" or "(grape) vine", itself derived from the Proto-Indo-European stem *win-o- (cf. Hittite: wiyana; Lycian: oino; Ancient Greek: οἶνος oinos; Aeolic Greek: ϝοῖνος woinos, Armenian: gini).[8][9][10]

The earliest attested terms referring to wine are the Mycenaean Greek 𐀕𐀶𐀺𐄀𐀚𐀺 me-tu-wo ne-wo (*μέθυϝος νέϝῳ),[11][12] meaning "in (the month)" or "(festival) of the new wine", and 𐀺𐀜𐀷𐀴𐀯 wo-no-wa-ti-si,[13] meaning "wine garden", written in Linear B inscriptions.[14][15][16][17] Linear B also includes, inter alia, an ideogram for wine, i.e. 𐂖.

Some scholars have noted the similarities between the words for wine in Kartvelian (e.g. Georgian ღვინო [ɣvinɔ]), Indo-European languages (e.g. Armenian gini, Latin vinum, Ancient Greek οἶνος, Russian вино [vʲɪˈno]), and Semitic (*wayn; Hebrew יין [jaiin]), pointing to the possibility of a common origin of the word denoting "wine" in these language families.[18] The Georgian word goes back to Proto-Kartvelian *ɣwino-,[19] which is probably borrowed from Proto-Armenian *ɣʷeinyo-,[20][21][22][23] whence Armenian gini. On the other hand, Fähnrich considers *ɣwino- a native Kartvelian word derived from the verbal root *ɣun- ('to bend').[24] See *ɣwino- for more.

Wines from other fruits, such as apples and berries, are usually named after the fruit from which they are produced combined with the word "wine" (for example, apple wine and elderberry wine) and are generically called fruit wine or country wine (not to be confused with the French term vin de pays). Besides the grape varieties traditionally used for winemaking, most fruits naturally lack either a high amount of fermentable sugars, relatively low acidity, yeast nutrients needed to promote or maintain fermentation or a combination of these three characteristics. This is probably one of the main reasons why wine derived from grapes has historically been more prevalent by far than other types and why specific types of fruit wine have generally been confined to regions in which the fruits were native or introduced for other reasons.

Other wines, such as barley wine and rice wine (e.g. sake), are made from starch-based materials and resemble beer more than wine, while ginger wine is fortified with brandy. In these latter cases, the term "wine" refers to the similarity in alcohol content rather than to the production process.[25] The commercial use of the English word "wine" (and its equivalent in other languages) is protected by law in many jurisdictions.[26]

History

A 2003 report by archaeologists indicates a possibility that grapes were mixed with rice to produce mixed fermented beverages in China in the early years of the seventh millennium BC. Pottery jars from the Neolithic site of Jiahu, Henan, contained traces of tartaric acid and other organic compounds commonly found in wine. However, other fruits indigenous to the region, such as hawthorn, cannot be ruled out.[29][30] If these beverages, which seem to be the precursors of rice wine, included grapes rather than other fruits, they would have been any of the several dozen indigenous wild species in China, rather than Vitis vinifera, which was introduced there some 6,000 years later.[29]

The spread of wine culture westwards was most probably due to the Phoenicians who spread outward from a base of city-states along the Lebanese and Israeli coast.[31] The wines of Byblos were exported to Egypt during the Old Kingdom and then throughout the Mediterranean. Evidence includes two Phoenician shipwrecks from 750 BC discovered by Robert Ballard, whose cargo of wine was still intact.[32] As the first great traders in wine (cherem), the Phoenicians seem to have protected it from oxidation with a layer of olive oil, followed by a seal of pinewood and resin, again similar to retsina.

Literary references to wine are abundant in Homer (8th century BC, but possibly relating earlier compositions), Alkman (7th century BC), and others. In ancient Egypt, six of 36 wine amphoras were found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun bearing the name "Kha'y", a royal chief vintner. Five of these amphoras were designated as originating from the king's personal estate, with the sixth from the estate of the royal house of Aten.[33] Traces of wine have also been found in central Asian Xinjiang in modern-day China, dating from the second and first millennia BC.[34]

The first known mention of grape-based wines in India is from the late 4th-century BC writings of Chanakya, the chief minister of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. In his writings, Chanakya condemns the use of alcohol while chronicling the emperor and his court's frequent indulgence of a style of wine known as madhu.[35]

The ancient Romans planted vineyards near garrison towns so wine could be produced locally rather than shipped over long distances. Some of these areas are now world renowned for wine production.[36] The Romans discovered that burning sulfur candles inside empty wine vessels keeps them fresh and free from a vinegar smell.[37] In medieval Europe, the Roman Catholic Church supported wine because the clergy required it for the Mass. Monks in France made wine for years, aging it in caves.[38] An old English recipe that survived in various forms until the 19th century calls for refining white wine from bastard—bad or tainted bastardo wine.[39]

Grape varieties

Wine is usually made from one or more varieties of the European species Vitis vinifera, such as Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay and Merlot. When one of these varieties is used as the predominant grape (usually defined by law as minimums of 75% to 85%), the result is a "varietal" as opposed to a "blended" wine. Blended wines are not considered inferior to varietal wines, rather they are a different style of winemaking; some of the world's most highly regarded wines, from regions like Bordeaux and the Rhone Valley, are blended from different grape varieties.[citation needed]Wine can also be made from other species of grape or from hybrids, created by the genetic crossing of two species. V. labrusca (of which the Concord grape is a cultivar), V. aestivalis, V. ruprestris, V. rotundifolia and V. riparia are native North American grapes usually grown to eat fresh or for grape juice, jam, or jelly, and only occasionally made into wine.

Hybridization is different from grafting. Most of the world's vineyards are planted with European V. vinifera vines that have been grafted onto North American species' rootstock, a common practice due to their resistance to phylloxera, a root louse that eventually kills the vine. In the late 19th century, most of Europe's vineyards (excluding some of the driest in the south) were devastated by the infestation, leading to widespread vine deaths and eventual replanting. Grafting is done in every wine-producing region in the world except in Argentina, the Canary Islands and Chile—the only places not yet exposed to the insect.[40]

In the context of wine production, terroir is a concept that encompasses the varieties of grapes used, elevation and shape of the vineyard, type and chemistry of soil, climate and seasonal conditions, and the local yeast cultures.[41] The range of possible combinations of these factors can result in great differences among wines, influencing the fermentation, finishing, and aging processes as well. Many wineries use growing and production methods that preserve or accentuate the aroma and taste influences of their unique terroir.[42] However, flavor differences are less desirable for producers of mass-market table wine or other cheaper wines, where consistency takes precedence. Such producers try to minimize differences in sources of grapes through production techniques such as micro-oxygenation, tannin filtration, cross-flow filtration, thin-film evaporation, and spinning cones.[43]

Classification

Regulations govern the classification and sale of wine in many regions of the world. European wines tend to be classified by region (e.g. Bordeaux, Rioja and Chianti), while non-European wines are most often classified by grape (e.g. Pinot noir and Merlot). Market recognition of particular regions has recently been leading to their increased prominence on non-European wine labels. Examples of recognized non-European locales include Napa Valley, Santa Clara Valley and Sonoma Valley in California; Willamette Valley in Oregon; Columbia Valley in Washington; Barossa Valley in South Australia and Hunter Valley in New South Wales; Luján de Cuyo in Argentina; Central Valley in Chile; Vale dos Vinhedos in Brazil; Hawke's Bay and Marlborough in New Zealand; and Okanagan Valley and Niagara Peninsula in Canada.Some blended wine names are marketing terms whose use is governed by trademark law rather than by specific wine laws. For example, Meritage (sounds like "heritage") is generally a Bordeaux-style blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, but may also include Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, and Malbec. Commercial use of the term Meritage is allowed only via licensing agreements with the Meritage Association.

European classifications[edit]

France has various appellation systems based on the concept of terroir, with classifications ranging from Vin de Table ("table wine") at the bottom, through Vin de Pays and Appellation d'Origine Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (AOVDQS), up to Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) or similar, depending on the region.[44][45] Portugal has developed a system resembling that of France and, in fact, pioneered this concept in 1756 with a royal charter creating the Demarcated Douro Region and regulating the production and trade of wine.[46] Germany created a similar scheme in 2002, although it has not yet achieved the authority of the other countries' classification systems.[47][48] Spain, Greece and Italy have classifications based on a dual system of region of origin and product quality.[49]Beyond Europe

New World wines—those made outside the traditional wine regions of Europe—are usually classified by grape rather than by terroir or region of origin, although there have been unofficial attempts to classify them by quality.[50][51]Vintages

In the United States, for a wine to be vintage-dated and labeled with a country of origin or American Viticultural Area (AVA) (e.g. Sonoma Valley), 95% of its volume must be from grapes harvested in that year.[52] If a wine is not labeled with a country of origin or AVA the percentage requirement is lowered to 85%.[52]Vintage wines are generally bottled in a single batch so that each bottle will have a similar taste. Climate's impact on the character of a wine can be significant enough to cause different vintages from the same vineyard to vary dramatically in flavor and quality.[53] Thus, vintage wines are produced to be individually characteristic of the particular vintage and to serve as the flagship wines of the producer. Superior vintages from reputable producers and regions will often command much higher prices than their average ones. Some vintage wines (e.g. Brunello), are only made in better-than-average years.

For consistency, non-vintage wines can be blended from more than one vintage, which helps winemakers sustain a reliable market image and maintain sales even in bad years.[54][55] One recent study suggests that for the average wine drinker, the vintage year may not be as significant for perceived quality as had been thought, although wine connoisseurs continue to place great importance on it.[56]

Tasting

Some wine labels suggest opening the bottle and letting the wine "breathe" for a couple of hours before serving, while others recommend drinking it immediately. Decanting (the act of pouring a wine into a special container just for breathing) is a controversial subject among wine enthusiasts. In addition to aeration, decanting with a filter allows the removal of bitter sediments that may have formed in the wine. Sediment is more common in older bottles, but aeration may benefit younger wines.[57]

During aeration, a younger wine's exposure to air often "relaxes" the drink, making it smoother and better integrated in aroma, texture, and flavor. Older wines generally "fade" (lose their character and flavor intensity) with extended aeration.[58] Despite these general rules, breathing does not necessarily benefit all wines. Wine may be tasted as soon as the bottle is opened to determine how long it should be aerated, if at all.[citation needed]

When tasting wine, individual flavors may also be detected, due to the complex mix of organic molecules (e.g. esters and terpenes) that grape juice and wine can contain. Experienced tasters can distinguish between flavors characteristic of a specific grape and flavors that result from other factors in winemaking. Typical intentional flavor elements in wine—chocolate, vanilla, or coffee—are those imparted by aging in oak casks rather than the grape itself.[59]

Vertical and horizontal tasting involves a range of vintages within the same grape and vineyard, or the latter in which there is one vintage from multiple vineyards.

Banana flavors (isoamyl acetate) are the product of yeast metabolism, as are spoilage aromas such as sweaty, barnyard, band-aid (4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol),[60] and rotten egg (hydrogen sulfide).[61] Some varieties can also exhibit a mineral flavor due to the presence of water-soluble salts as a result of limestone's presence in the vineyard's soil.

Wine aroma comes from volatile compounds released into the air.[62] Vaporization of these compounds can be accelerated by twirling the wine glass or serving at room temperature. Many drinkers prefer to chill red wines that are already highly aromatic, like Chinon and Beaujolais.[63]

The ideal temperature for serving a particular wine is a matter of debate, but some broad guidelines have emerged that will generally enhance the experience of tasting certain common wines. A white wine should foster a sense of coolness, achieved by serving at "cellar temperature" (13 °C [55 °F]). Light red wines drunk young should also be brought to the table at this temperature, where they will quickly rise a few degrees. Red wines are generally perceived best when served chambré ("at room temperature"). However, this does not mean the temperature of the dining room—often around (21 °C [70 °F])—but rather the coolest room in the house and, therefore, always slightly cooler than the dining room itself. Pinot noir should be brought to the table for serving at (16 °C [61 °F]) and will reach its full bouquet at (18 °C [64 °F]). Cabernet Sauvignon, zinfandel, and Rhone varieties should be served at (18 °C [64 °F]) and allowed to warm on the table to 21 °C (70 °F) for best aroma.[64]

Collecting

Outstanding vintages from the best vineyards may sell for thousands of dollars per bottle, though the broader term "fine wine" covers those typically retailing in excess of US$30–50.[65] "Investment wines" are considered by some to be Veblen goods: those for which demand increases rather than decreases as their prices rise. Particular selections have higher value, such as "Verticals", in which a range of vintages of a specific grape and vineyard, are offered. The most notable was a Chateau d'Yquem 135 year vertical containing every vintage from 1860 to 2003 sold for $1.5 million. The most common wines purchased for investment include those from Bordeaux and Burgundy; cult wines from Europe and elsewhere; and vintage port. Characteristics of highly collectible wines include:- A proven track record of holding well over time

- A drinking-window plateau (i.e., the period for maturity and approachability) that is many years long

- A consensus among experts as to the quality of the wines

- Rigorous production methods at every stage, including grape selection and appropriate barrel aging

Production

In 2012, Italy was the top producer of wine in the world, followed by France, Spain, the United States and Argentina.[citation needed]

|

| Rank | Country (with link to wine article) |

Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,349,330 | |

| 2 | 4,963,300 | |

| 3 | 3,890,730 | |

| 4 | 2,250,000 | |

| 5 | 1,539,600 | |

| 6 | 1,429,790 | |

| 7 | 1,400,000 | |

| 8 | 939,779 | |

| 9 | 891,600 | |

| 10 | 802,441 | |

| World** | 28,475,929 | |

** May include official, semi-official or estimated data.

| Rank | Country (with link to wine article) |

Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4,711,600 | |

| 2 | 4,251,380 | |

| 3 | 3,520,870 | |

| 4 | 2,259,870 | |

| 5 | 1,504,600 | |

| 6 | 1,450,000 | |

| 7 | 1,026,100 | |

| 8 | 978,269 | |

| 9 | 961,972 | |

| 10 | 791,794 | |

| World** | 26,416,532 | |

** May include official, semi-official or estimated data.

*** FAO data based on imputation methodology.

Wine grapes grow almost exclusively between 30 and 50 degrees latitude north and south of the equator. The world's southernmost vineyards are in the Central Otago region of New Zealand's South Island near the 45th parallel south,[70] and the northernmost are in Flen, Sweden, just north of the 59th parallel north.[71]

Exporting countries

** May include official, semi-official or estimated data. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The UK was the world's largest importer of wine in 2007.[73]

Wine production in the European Union in 2005 and 2006

2005 Estimate (thousands of hectoliters)

2006 Estimate (thousands of hectoliters)

2006 Estimate (thousands of hectoliters)

- Italy: 52,036

- France: 51,700

- Spain: 39,301

- Germany: 8,995

- Portugal: 7,390

- Greece: 3,908

World production in 2003[edit]

In 2003, world wine production had reached 269 millions of hectoliters. The world's main 15 wine producers were:| Country | millions of hectoliters |

|---|---|

| France | 47.3 |

| Italy | 46.8 |

| Spain | 39.5 |

| USA | 23.5 |

| Australia | 12.6 |

| Argentina | 12.2 |

| China | 10.8 |

| Germany | 10.2 |

| South Africa | 7.6 |

| Portugal | 6.8 |

| Chile | 5.8 |

| Romania | 5.5 |

| Greece | 4.2 |

| Russia | 4.1 |

| Hungary | 4.0 |

The world's 10 main wine exporting countries in 2005

| Country | thousands of hectoliters |

|---|---|

| Italy | 15,100 |

| Spain | 14,439 |

| France | 13,900 |

| Australia | 7,019 |

| Chile | 4,209 |

| USA | 3,482 |

| Germany | 2,970 |

| South Africa | 2,818 |

| Portugal | 2,800 |

| Moldova | 2,425 |

| TOTAL | 78,729 |

The top 5 countries for wine production in 2008

Country Wine Production 2009 Percentage of World Total1 Italy 4,994,940 metric tonnes 18.42%

2 France 4,552,077 metric tonnes 16.79%

3 Spain 3,250,610 metric tonnes 11.99%

4 United States 2,250,000 metric tonnes 8.30%

5 China 1,580,000 metric tonnes 5.82%

Sources: FAOSTAT data 2008 (last accessed by Top 5 of Anything: Nov, 2010)

The Wine Institute, a nonprofit group, tracked that the U.S. has been the largest wine consuming nation in the world since 2010, with residents individually consuming a total of 2.82 gallons a year in 2013, up from under 2 gallons in 1979.[74] Wine shipments within the U.S. from California alone were 215 million cases in 2013, up 3% from the previous year, with an estimated retail value of $23.1 billion, up 5%.[75] All American regions produce wine however, 95% comes from four regions with California as the most prolific producer, followed by Washington, Oregon and New York.

Consumption

Wine-consumption data from a list of countries by alcohol consumption measured in liters of pure ethyl alcohol consumed per capita in a given year, according to the most recent data from the World Health Organization. The methodology includes persons 15 years of age or older.[76]

|

|

Uses

Wine is an alcoholic beverage used as food drink, psychoactive drug, and sometimes intended for use as medicine.

Wine is a popular and important beverage that accompanies and enhances a wide range of cuisines, from the simple and traditional to the most sophisticated and complex. Wine is important in cuisine not just for its value as a beverage, but as a flavor agent, primarily in stocks and braising, since its acidity lends balance to rich savory or sweet dishes. Wine sauce is an example of a culinary sauce that uses wine as a primary ingredient.[77] Natural wines may exhibit a broad range of alcohol content, from below 9% to above 16% ABV, with most wines being in the 12.5%–14.5% range.[78] Fortified wines (usually with brandy) may contain 20% alcohol or more.

Religious significance

Ancient religions

The use of wine in ancient Near Eastern and Ancient Egyptian religious ceremonies was common. Libations often included wine, and the religious mysteries of Dionysus used wine as a sacramental entheogen to induce a mind-altering state.Judaism

| “ | Baruch atah Hashem (Ado-nai) Eloheinu melech ha-olam, boray p’ree hagafen – Praised be the Lord, our God, King of the universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine. | ” |

—The blessing over wine said before consuming the drink.

|

||

Christianity

Jesus making wine from water in The Marriage at Cana, a 14th-century fresco from the Visoki Dečani monastery

All alcohol is prohibited under Islamic law, although there has been a long tradition of drinking wine in some Islamic areas, especially in Persia.

In Christianity, wine is used in a sacred rite called the Eucharist, which originates in the Gospel account of the Last Supper (Gospel of Luke 22:19) describing Jesus sharing bread and wine with his disciples and commanding them to "do this in remembrance of me." Beliefs about the nature of the Eucharist vary among denominations (see Eucharistic theologies contrasted).

While some Christians consider the use of wine from the grape as essential for the validity of the sacrament, many Protestants also allow (or require) pasteurized grape juice as a substitute. Wine was used in Eucharistic rites by all Protestant groups until an alternative arose in the late 19th century. Methodist dentist and prohibitionist Thomas Bramwell Welch applied new pasteurization techniques to stop the natural fermentation process of grape juice. Some Christians who were part of the growing temperance movement pressed for a switch from wine to grape juice, and the substitution spread quickly over much of the United States, as well as to other countries to a lesser degree.[82] There remains an ongoing debate between some American Protestant denominations as to whether wine can and should be used for the Eucharist or allowed as an ordinary beverage, with Catholics and some mainline Protestants allowing wine drinking in moderation, and some conservative Protestant groups opposing consumption of alcohol altogether.

Certain exceptions to the ban on alcohol apply. Alcohol derived from a source other than the grape (or its byproducts) and the date[85] is allowed in "very small quantities" (loosely defined as a quantity that does not cause intoxication) under the Sunni Hanafi madhab, for specific purposes (such as medicines), where the goal is not intoxication. However, modern Hanafi scholars regard alcohol consumption as totally forbidden.[86]

Studies of the health effects of wine have focused on cardiovascular health, cancer, Alzheimer's disease, alcoholism, cirrhosis of the liver, and oral bacteria. Although excessive alcohol consumption has adverse health effects, epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated that moderate consumption of alcohol and wine is statistically associated with a decrease in cardiovascular illness such as heart failure.[87] Additional news reports on the French paradox also back the relationship.[88] This paradox concerns the comparatively low incidence of coronary heart disease in France despite relatively high levels of saturated fat in the traditional French diet. Some epidemiologists suspect that this is due to higher wine consumption by the French, but the scientific evidence for this theory is limited. Because the average moderate wine drinker is likely to exercise more often, to be more health conscious, and to be from a higher educational and socioeconomic background, the association between moderate wine drinking and better health may be related to confounding factors or represent a correlation rather than cause and effect.[87]

Population studies have observed a J-curve correlation between wine consumption and the prevalence of heart disease: heavy drinkers have an elevated prevalence, while moderate drinkers (up to 20g of alcohol per day, approximately 200 ml (7 imp fl oz; 7 US fl oz) of 12.7% ABV wine) have a lower prevalence than non-drinkers. Studies have also found that moderate consumption of other alcoholic beverages is correlated with decreased mortality from cardiovascular causes,[89] although the association is stronger for wine. Additionally, some studies have found a greater correlation of health benefits with red than white wine, though other studies have found no difference. Red wine contains more polyphenols than white wine, and these could be protective against cardiovascular disease.[87]

A chemical in grapes, red wine, peanuts and blueberries called resveratrol has been shown to have both cardioprotective and chemoprotective effects in animal studies.[90][91][92][93] Low doses of resveratrol in the diet of middle-aged mice has a widespread influence on the genetic factors related to aging and may confer special protection on the heart. Specifically, low doses of resveratrol mimic the effects of caloric restriction—diets with 20–30% fewer calories than a typical diet.[94] Resveratrol is produced naturally by grape skins in response to fungal infection, including exposure to yeast during fermentation. As white wine has minimal contact with grape skins during this process, it generally contains lower levels of the chemical.[95] Beneficial compounds in wine also include other polyphenols, antioxidants, and flavonoids.[96]

Sipping slowly when drinking may result in optimal absorption of the resveratrol in wine. Due to inactivation in the gut and liver, most of the resveratrol consumed while drinking red wine does not reach the blood circulation. However, when sipping slowly, absorption via the mucous membranes in the mouth can result in up to 100 times the blood levels of resveratrol, according to Stephen Taylor, Ph.D.[97]

Red wines from the south of France and from Sardinia in Italy have the highest levels of procyanidins, compounds in grape seeds which could be responsible for red wine's heart benefits. Red wines from these areas contain between two and four times as much procyanidins as other red wines tested. Procyanidins suppress the synthesis of a peptide called endothelin-1 that constricts blood vessels.[98]

A 2007 study found that both red and white wines are effective antibacterial agents against strains of Streptococcus.[99] In addition, a report in the October 2008 issue of Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention posits that moderate consumption of red wine may decrease the risk of lung cancer in men.[100]

While evidence from laboratory and epidemiological (observational) studies suggest a cardioprotective effect, no controlled studies have been completed on the effect of alcoholic beverages on the risk of developing heart disease or stroke. Excessive consumption of alcohol can cause cirrhosis of the liver and alcoholism;[101] the American Heart Association states that "the American Heart Association cautions people NOT to start drinking ... if they do not already drink alcohol. Consult your doctor on the benefits and risks of consuming alcohol in moderation."[102]

Wine's effect on the brain is also under study. One study concluded that wine made from the Cabernet Sauvignon grape reduces the risk of Alzheimer's Disease.[103][104] Another study found that among alcoholics, wine damages the hippocampus, a brain area involved in memory processes, to a greater degree than other alcoholic beverages.[105]

Sulfites in wine can cause some people, particularly those with asthma, to have adverse reactions. Sulfites are present in all wines and are formed as a natural product of the fermentation process; many winemakers add sulfur dioxide in order to help preserve wine. Sulfur dioxide is also added to foods such as dried apricots and orange juice. The level of added sulfites varies; some wines have been marketed with low sulfite content.[106]

A study of women in the United Kingdom, called The Million Women Study, concluded that moderate alcohol consumption can increase the risk of certain cancers, including breast, pharynx and liver cancer.[107] Lead author of the study, Professor Valerie Beral, asserted that there is scant evidence that any positive health effects of red wine outweigh the risk of cancer. She said, "It's an absolute myth that red wine is good for you." Professor Roger Corder, author of the bestselling bookThe Red Wine Diet, countered that two small glasses of a very tannic, procyanidin-rich wine would confer a benefit, although "most supermarket wines are low-procyanidin and high-alcohol."[108] No professional medical association recommends that people who are nondrinkers should start drinking wine.[109]

Most wines are sold in glass bottles and sealed with corks (50% of which come from Portugal).[113] An increasing number of wine producers have been using alternative closures such as screwcaps and synthetic plastic "corks". Although alternative closures are less expensive and prevent cork taint, they have been blamed for such problems as excessive reduction.[citation needed]

Some wines are packaged in thick plastic bags within corrugated fiberboard boxes, and are called "box wines", or "cask wine". Tucked inside the package is a tap affixed to the bag in box, or bladder, that is later extended by the consumer for serving the contents. Box wine can stay acceptably fresh for up to a month after opening because the bladder collapses as wine is dispensed, limiting contact with air and, thus, slowing the rate of oxidation. In contrast, bottled wine oxidizes more rapidly after opening because of the increasing ratio of air to wine as the contents are dispensed; it can degrade considerably in a few days.

Environmental considerations of wine packaging reveal benefits and drawbacks of both bottled and box wines. The glass used to make bottles is a nontoxic, naturally occurring substance that is completely recyclable, whereas the plastics used for box-wine containers are typically much less environmentally friendly. However, wine-bottle manufacturers have been cited for Clean Air Act violations. A New York Times editorial suggested that box wine, being lighter in package weight, has a reduced carbon footprint from its distribution; however, box-wine plastics, even though possibly recyclable, can be more labor-intensive (and therefore expensive) to process than glass bottles. In addition, while a wine box is recyclable, its plastic bladder most likely is not.[114]

While some Christians consider the use of wine from the grape as essential for the validity of the sacrament, many Protestants also allow (or require) pasteurized grape juice as a substitute. Wine was used in Eucharistic rites by all Protestant groups until an alternative arose in the late 19th century. Methodist dentist and prohibitionist Thomas Bramwell Welch applied new pasteurization techniques to stop the natural fermentation process of grape juice. Some Christians who were part of the growing temperance movement pressed for a switch from wine to grape juice, and the substitution spread quickly over much of the United States, as well as to other countries to a lesser degree.[82] There remains an ongoing debate between some American Protestant denominations as to whether wine can and should be used for the Eucharist or allowed as an ordinary beverage, with Catholics and some mainline Protestants allowing wine drinking in moderation, and some conservative Protestant groups opposing consumption of alcohol altogether.

Islam

Alcoholic beverages, including wine, are forbidden under most interpretations of Islamic law.[83] Iran had previously had a thriving wine industry that disappeared after the Islamic Revolution in 1979.[84] In Greater Persia, mey (Persian wine) was a central theme of poetry for more than a thousand years, long before the advent of Islam. Some Alevi sects use wine in their religious services.Certain exceptions to the ban on alcohol apply. Alcohol derived from a source other than the grape (or its byproducts) and the date[85] is allowed in "very small quantities" (loosely defined as a quantity that does not cause intoxication) under the Sunni Hanafi madhab, for specific purposes (such as medicines), where the goal is not intoxication. However, modern Hanafi scholars regard alcohol consumption as totally forbidden.[86]

Health effects

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 355 kJ (85 kcal) |

2.6 g

|

|

| Sugars | 0.6 g |

0.0 g

|

|

0.1 g

|

|

| Other constituents | |

| 10.6 g | |

10.6 g alcohol is 13%vol.

100 g wine is approximately 100 ml (3.4 fl oz.) Sugar and alcohol content can vary. |

|

|

|

Source: USDA Nutrient Database |

|

Population studies have observed a J-curve correlation between wine consumption and the prevalence of heart disease: heavy drinkers have an elevated prevalence, while moderate drinkers (up to 20g of alcohol per day, approximately 200 ml (7 imp fl oz; 7 US fl oz) of 12.7% ABV wine) have a lower prevalence than non-drinkers. Studies have also found that moderate consumption of other alcoholic beverages is correlated with decreased mortality from cardiovascular causes,[89] although the association is stronger for wine. Additionally, some studies have found a greater correlation of health benefits with red than white wine, though other studies have found no difference. Red wine contains more polyphenols than white wine, and these could be protective against cardiovascular disease.[87]

A chemical in grapes, red wine, peanuts and blueberries called resveratrol has been shown to have both cardioprotective and chemoprotective effects in animal studies.[90][91][92][93] Low doses of resveratrol in the diet of middle-aged mice has a widespread influence on the genetic factors related to aging and may confer special protection on the heart. Specifically, low doses of resveratrol mimic the effects of caloric restriction—diets with 20–30% fewer calories than a typical diet.[94] Resveratrol is produced naturally by grape skins in response to fungal infection, including exposure to yeast during fermentation. As white wine has minimal contact with grape skins during this process, it generally contains lower levels of the chemical.[95] Beneficial compounds in wine also include other polyphenols, antioxidants, and flavonoids.[96]

Sipping slowly when drinking may result in optimal absorption of the resveratrol in wine. Due to inactivation in the gut and liver, most of the resveratrol consumed while drinking red wine does not reach the blood circulation. However, when sipping slowly, absorption via the mucous membranes in the mouth can result in up to 100 times the blood levels of resveratrol, according to Stephen Taylor, Ph.D.[97]

Red wines from the south of France and from Sardinia in Italy have the highest levels of procyanidins, compounds in grape seeds which could be responsible for red wine's heart benefits. Red wines from these areas contain between two and four times as much procyanidins as other red wines tested. Procyanidins suppress the synthesis of a peptide called endothelin-1 that constricts blood vessels.[98]

A 2007 study found that both red and white wines are effective antibacterial agents against strains of Streptococcus.[99] In addition, a report in the October 2008 issue of Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention posits that moderate consumption of red wine may decrease the risk of lung cancer in men.[100]

While evidence from laboratory and epidemiological (observational) studies suggest a cardioprotective effect, no controlled studies have been completed on the effect of alcoholic beverages on the risk of developing heart disease or stroke. Excessive consumption of alcohol can cause cirrhosis of the liver and alcoholism;[101] the American Heart Association states that "the American Heart Association cautions people NOT to start drinking ... if they do not already drink alcohol. Consult your doctor on the benefits and risks of consuming alcohol in moderation."[102]

Wine's effect on the brain is also under study. One study concluded that wine made from the Cabernet Sauvignon grape reduces the risk of Alzheimer's Disease.[103][104] Another study found that among alcoholics, wine damages the hippocampus, a brain area involved in memory processes, to a greater degree than other alcoholic beverages.[105]

Sulfites in wine can cause some people, particularly those with asthma, to have adverse reactions. Sulfites are present in all wines and are formed as a natural product of the fermentation process; many winemakers add sulfur dioxide in order to help preserve wine. Sulfur dioxide is also added to foods such as dried apricots and orange juice. The level of added sulfites varies; some wines have been marketed with low sulfite content.[106]

A study of women in the United Kingdom, called The Million Women Study, concluded that moderate alcohol consumption can increase the risk of certain cancers, including breast, pharynx and liver cancer.[107] Lead author of the study, Professor Valerie Beral, asserted that there is scant evidence that any positive health effects of red wine outweigh the risk of cancer. She said, "It's an absolute myth that red wine is good for you." Professor Roger Corder, author of the bestselling bookThe Red Wine Diet, countered that two small glasses of a very tannic, procyanidin-rich wine would confer a benefit, although "most supermarket wines are low-procyanidin and high-alcohol."[108] No professional medical association recommends that people who are nondrinkers should start drinking wine.[109]

Honoré Daumier: All These Grapes Seem to Have Fallen Ill… (Tous ces raisins me font l'effet d'avoir la maladie…)

Forgery and manipulation of wines

Incidents of fraud, such as mislabeling the origin or quality of wines, have resulted in regulations on labeling. "Wine scandals" that have received media attention include:- The 1985 Diethylene Glycol Wine Scandal, in which diethylene glycol was used as a sweetener in some Austrian wines.

- In 1986, methanol (a toxic type of alcohol) was used to alter certain wines manufactured in Italy.

- In 2008, some Italian wines were found to include sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid.[110]

- In 2010, some Chinese red wines were found to be adulterated, and as a consequence China's Hebei province has shut down nearly 30 wineries.[111][112]

Packaging

Some wines are packaged in thick plastic bags within corrugated fiberboard boxes, and are called "box wines", or "cask wine". Tucked inside the package is a tap affixed to the bag in box, or bladder, that is later extended by the consumer for serving the contents. Box wine can stay acceptably fresh for up to a month after opening because the bladder collapses as wine is dispensed, limiting contact with air and, thus, slowing the rate of oxidation. In contrast, bottled wine oxidizes more rapidly after opening because of the increasing ratio of air to wine as the contents are dispensed; it can degrade considerably in a few days.

Environmental considerations of wine packaging reveal benefits and drawbacks of both bottled and box wines. The glass used to make bottles is a nontoxic, naturally occurring substance that is completely recyclable, whereas the plastics used for box-wine containers are typically much less environmentally friendly. However, wine-bottle manufacturers have been cited for Clean Air Act violations. A New York Times editorial suggested that box wine, being lighter in package weight, has a reduced carbon footprint from its distribution; however, box-wine plastics, even though possibly recyclable, can be more labor-intensive (and therefore expensive) to process than glass bottles. In addition, while a wine box is recyclable, its plastic bladder most likely is not.[114]

Storage

Wine cellars, or wine rooms, if they are above-ground, are places designed specifically for the storage and aging of wine. In an "active" wine cellar, temperature and humidity are maintained by a climate-control system. "Passive" wine cellars are not climate-controlled, and so must be carefully located. Because wine is a natural, perishable food product, all types—including red, white, sparkling, and fortified—can spoil when exposed to heat, light, vibration or fluctuations in temperature and humidity. When properly stored, wines can maintain their quality and in some cases improve in aroma, flavor, and complexity as they age. Some wine experts contend that the optimal temperature for aging wine is 13 °C (55 °F),[115] others 15 °C (59 °F).[116] Wine refrigerators offer an alternative to wine cellars and are available in capacities ranging from small, 16-bottle units to furniture-quality pieces that can contain 400 bottles. Wine refrigerators are not ideal for aging, but rather serve to chill wine to the perfect temperature for drinking. These refrigerators keep the humidity low (usually under 50%), below the optimal humidity of 50% to 70%. Lower humidity levels can dry out corks over time, allowing oxygen to enter the bottle, which reduces the wine's quality through oxidation.[117]Professions

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Cooper | A craftsperson of wooden barrels and casks. A cooperage is a facility that produces such casks |

| Négociant | A wine merchant that purchases the product of smaller growers and/or winemakers to sell them under its own name |

| Oenologist | A wine scientist or wine chemist; a student of oenology. A winemaker may be trained as an oenologist, but often hires one as a consultant |

| Sommelier | A specialist in charge of developing a restaurant's wine list, educating the staff about wine, and assisting customers with their selections |

| Vintner, Winemaker | A wine producer; a person who makes wine |

| Viticulturist | A specialist in the science of grapevines; a manager of vineyard pruning, irrigation, and pest control |