From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The temperature of an ideal monatomic gas is proportional to the average kinetic energy of its atoms. The size of helium atoms relative to their spacing is shown to scale under 1950 atmospheres of pressure. The atoms have a certain, average speed, slowed down here two trillion fold from room temperature.

Under a microscope, the molecules making up a liquid are too small to be visible, but the jittering motion of pollen grains or dust particles can be seen. Known as Brownian motion, it results directly from collisions between the grains or particles and liquid molecules. As analyzed by Albert Einstein in 1905, this experimental evidence for kinetic theory is generally seen as having confirmed the concrete material existence of atoms and molecules.

Assumptions

The theory for ideal gases makes the following assumptions:- The gas consists of very small particles known as molecules. This smallness of their size is such that the total volume of the individual gas molecules added up is negligible compared to the volume of the smallest open ball containing all the molecules. This is equivalent to stating that the average distance separating the gas particles is large compared to their size.

- These particles have the same mass.

- The number of molecules is so large that statistical treatment can be applied.

- These molecules are in constant, random, and rapid motion.

- The rapidly moving particles constantly collide among themselves and with the walls of the container. All these collisions are perfectly elastic. This means, the molecules are considered to be perfectly spherical in shape, and elastic in nature.

- Except during collisions, the interactions among molecules are negligible. (That is, they exert no forces on one another.)

- This implies:

- 1. Relativistic effects are negligible.

- 2. Quantum-mechanical effects are negligible. This means that the inter-particle distance is much larger than the thermal de Broglie wavelength and the molecules are treated as classical objects.

- 3. Because of the above two, their dynamics can be treated classically. This means, the equations of motion of the molecules are time-reversible.

- The average kinetic energy of the gas particles depends only on the absolute temperature of the system. The kinetic theory has its own definition of temperature, not identical with the thermodynamic definition.

- The time during collision of molecule with the container's wall is negligible as compared to the time between successive collisions.

- Because they have mass, the gas molecules will be affected by gravity.

An important book on kinetic theory is that by Chapman and Cowling.[1] An important approach to the subject is called Chapman–Enskog theory.[2] There have been many modern developments and there is an alternative approach developed by Grad based on moment expansions.[3] In the other limit, for extremely rarefied gases, the gradients in bulk properties are not small compared to the mean free paths. This is known as the Knudsen regime and expansions can be performed in the Knudsen number.

Properties

Pressure and kinetic energy

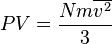

Pressure is explained by kinetic theory as arising from the force exerted by molecules or atoms impacting on the walls of a container. Consider a gas of N molecules, each of mass m, enclosed in a cuboidal container of volume V=L3. When a gas molecule collides with the wall of the container perpendicular to the x coordinate axis and bounces off in the opposite direction with the same speed (an elastic collision), then the momentum lost by the particle and gained by the wall is:The particle impacts one specific side wall once every

The force due to this particle is:

.

.

which is a microscopic property.

which is a microscopic property.Temperature and kinetic energy

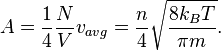

Rewriting the above result for the pressure as , we may combine it with the ideal gas law

, we may combine it with the ideal gas law (1)

(1)

is the Boltzmann constant and

is the Boltzmann constant and  the absolute temperature defined by the ideal gas law, to obtain

the absolute temperature defined by the ideal gas law, to obtain ,

,

.

.

. Then the temperature

. Then the temperature  takes the form

takes the form (2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Eq.(1) and Eq.(4) are called the "classical results", which could also be derived from statistical mechanics; for more details, see .[4]

Since there are

degrees of freedom in a monatomic-gas system with

degrees of freedom in a monatomic-gas system with  particles, the kinetic energy per degree of freedom per molecule is

particles, the kinetic energy per degree of freedom per molecule is (5)

(5)

As noted in the article on heat capacity, diatomic gases should have 7 degrees of freedom, but the lighter gases act as if they have only 5.

Thus the kinetic energy per kelvin (monatomic ideal gas) is:

- per mole: 12.47 J

- per molecule: 20.7 yJ = 129 μeV.

- per mole: 3406 J

- per molecule: 5.65 zJ = 35.2 meV.....

Collisions with container

One can calculate the number of atomic or molecular collisions with a wall of a container per unit area per unit time.Assuming an ideal gas, a derivation[5] results in an equation for total number of collisions per unit time per area:

Speed of molecules

From the kinetic energy formula it can be shown thatTransport properties

The kinetic theory of gases deals not only with gases in thermodynamic equilibrium, but also very importantly with gases not in thermodynamic equilibrium. This means considering what are known as 'transport properties', such a viscosity and thermal conductivity.History

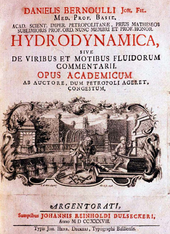

In approximately 50 BCE, the Roman philosopher Lucretius proposed that apparently static macroscopic bodies were composed on a small scale of rapidly moving atoms all bouncing off each other.[6] This Epicurean atomistic point of view was rarely considered in the subsequent centuries, when Aristotlean ideas were dominant.In 1738 Daniel Bernoulli published Hydrodynamica, which laid the basis for the kinetic theory of gases. In this work, Bernoulli posited the argument, still used to this day, that gases consist of great numbers of molecules moving in all directions, that their impact on a surface causes the gas pressure that we feel, and that what we experience as heat is simply the kinetic energy of their motion. The theory was not immediately accepted, in part because conservation of energy had not yet been established, and it was not obvious to physicists how the collisions between molecules could be perfectly elastic.[7]:36–37

Other pioneers of the kinetic theory (which were neglected by their contemporaries) were Mikhail Lomonosov (1747),[8] Georges-Louis Le Sage (ca. 1780, published 1818),[9] John Herapath (1816)[10] and John James Waterston (1843),[11] which connected their research with the development of mechanical explanations of gravitation. In 1856 August Krönig (probably after reading a paper of Waterston) created a simple gas-kinetic model, which only considered the translational motion of the particles.[12]

In 1857 Rudolf Clausius, according to his own words independently of Krönig, developed a similar, but much more sophisticated version of the theory which included translational and contrary to Krönig also rotational and vibrational molecular motions. In this same work he introduced the concept of mean free path of a particle. [13] In 1859, after reading a paper by Clausius, James Clerk Maxwell formulated the Maxwell distribution of molecular velocities, which gave the proportion of molecules having a certain velocity in a specific range. This was the first-ever statistical law in physics.[14] In his 1873 thirteen page article 'Molecules', Maxwell states: "we are told that an 'atom' is a material point, invested and surrounded by 'potential forces' and that when 'flying molecules' strike against a solid body in constant succession it causes what is called pressure of air and other gases."[15] In 1871, Ludwig Boltzmann generalized Maxwell's achievement and formulated the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. Also the logarithmic connection between entropy and probability was first stated by him.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, however, atoms were considered by many physicists to be purely hypothetical constructs, rather than real objects. An important turning point was Albert Einstein's (1905)[16] and Marian Smoluchowski's (1906)[17] papers on Brownian motion, which succeeded in making certain accurate quantitative predictions based on the kinetic theory.

.

.

,

, .

.