In philosophy of mind, panpsychism (/pænˈsaɪkɪzəm/) is the view that the mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe". It is one of the oldest philosophical theories, and has been ascribed in some form to philosophers including Thales, Plato, Spinoza, Leibniz, Schopenhauer, William James, Alfred North Whitehead, and Bertrand Russell. In the 19th century, panpsychism was the default philosophy of mind in Western thought, but it saw a decline in the mid-20th century with the rise of logical positivism. Recent interest in the hard problem of consciousness and developments in the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and quantum mechanics have revived interest in panpsychism in the 21st century because it addresses the hard problem directly.

Overview

Etymology

The term panpsychism comes from the Greek pan (πᾶν: "all, everything, whole") and psyche (ψυχή: "soul, mind"). The use of "psyche" is controversial because it is synonymous with "soul", a term usually taken to refer to something supernatural; more common terms now found in the literature include mind, mental properties, mental aspect, and experience.

Concept

Panpsychism holds that mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is sometimes defined as a theory in which "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe". Panpsychists posit that the type of mentality we know through our own experience is present, in some form, in a wide range of natural bodies. This notion has taken on a wide variety of forms. Some historical and non-Western panpsychists ascribe attributes such as life or spirits to all entities (animism). Contemporary academic proponents, however, hold that sentience or subjective experience is ubiquitous, while distinguishing these qualities from more complex human mental attributes. They therefore ascribe a primitive form of mentality to entities at the fundamental level of physics but may not ascribe mentality to most aggregate things, such as rocks or buildings.

Terminology

The philosopher David Chalmers, who has explored panpsychism as a viable theory, distinguishes between microphenomenal experiences (the experiences of microphysical entities) and macrophenomenal experiences (the experiences of larger entities, such as humans).

Philip Goff draws a distinction between panexperientialism and pancognitivism. In the form of panpsychism under discussion in the contemporary literature, conscious experience is present everywhere at a fundamental level, hence the term panexperientialism. Pancognitivism, by contrast, is the view that thought is present everywhere at a fundamental level—a view that had some historical advocates, but no present-day academic adherents. Contemporary panpsychists do not believe microphysical entities have complex mental states such as beliefs, desires, and fears.

Originally, the term panexperientialism had a narrower meaning, having been coined by David Ray Griffin to refer specifically to the form of panpsychism used in process philosophy (see below).

History

Antiquity

Panpsychist views are a staple in pre-Socratic Greek philosophy. According to Aristotle, Thales (c. 624 – 545 BCE), the first Greek philosopher, posited a theory which held "that everything is full of gods". Thales believed that magnets demonstrated this. This has been interpreted as a panpsychist doctrine. Other Greek thinkers associated with panpsychism include Anaxagoras (who saw the unifying principle or arche as nous or mind), Anaximenes (who saw the arche as pneuma or spirit) and Heraclitus (who said "The thinking faculty is common to all").

Plato argues for panpsychism in his Sophist, in which he writes that all things participate in the form of Being and that it must have a psychic aspect of mind and soul (psyche). In the Philebus and Timaeus, Plato argues for the idea of a world soul or anima mundi. According to Plato:

This world is indeed a living being endowed with a soul and intelligence ... a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related.

Stoicism developed a cosmology that held that the natural world is infused with the divine fiery essence pneuma, directed by the universal intelligence logos. The relationship between beings' individual logos and the universal logos was a central concern of the Roman Stoic Marcus Aurelius. The metaphysics of Stoicism finds connections with Hellenistic philosophies such as Neoplatonism. Gnosticism also made use of the Platonic idea of anima mundi.

Renaissance

After Emperor Justinian closed Plato's Academy in 529 CE, neoplatonism declined. Though there were mediaeval theologians, such as John Scotus Eriugena, who ventured into what might be called panpsychism, it was not a dominant strain in philosophical theology. But in the Italian Renaissance, it enjoyed something of a revival in the thought of figures such as Gerolamo Cardano, Bernardino Telesio, Francesco Patrizi, Giordano Bruno, and Tommaso Campanella. Cardano argued for the view that soul or anima was a fundamental part of the world, and Patrizi introduced the term panpsychism into philosophical vocabulary. According to Bruno, "There is nothing that does not possess a soul and that has no vital principle". Platonist ideas resembling the anima mundi (world soul) also resurfaced in the work of esoteric thinkers such as Paracelsus, Robert Fludd, and Cornelius Agrippa.

Early modern

In the 17th century, two rationalists, Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, can be said to be panpsychists. In Spinoza's monism, the one single infinite and eternal substance is "God, or Nature" (Deus sive Natura), which has the aspects of mind (thought) and matter (extension). Leibniz's view is that there are infinitely many absolutely simple mental substances called monads that make up the universe's fundamental structure. While it has been said that George Berkeley's idealist philosophy is also a form of panpsychism, Berkeley rejected panpsychism and posited that the physical world exists only in the experiences minds have of it, while restricting minds to humans and certain other specific agents.

19th century

In the 19th century, panpsychism was at its zenith. Philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer, C.S. Peirce, Josiah Royce, William James, Eduard von Hartmann, F.C.S. Schiller, Ernst Haeckel, William Kingdon Clifford and Thomas Carlyle as well as psychologists such as Gustav Fechner, Wilhelm Wundt, Rudolf Hermann Lotze all promoted panpsychist ideas.

Arthur Schopenhauer argued for a two-sided view of reality as both Will and Representation (Vorstellung). According to Schopenhauer, "All ostensible mind can be attributed to matter, but all matter can likewise be attributed to mind".

Josiah Royce, the leading American absolute idealist, held that reality is a "world self", a conscious being that comprises everything, though he did not necessarily attribute mental properties to the smallest constituents of mentalistic "systems". The American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce espoused a sort of psycho-physical monism in which the universe is suffused with mind, which he associated with spontaneity and freedom. Following Pierce, William James also espoused a form of panpsychism. In his lecture notes, James wrote:

Our only intelligible notion of an object in itself is that it should be an object for itself, and this lands us in panpsychism and a belief that our physical perceptions are effects on us of 'psychical' realities

English philosopher Alfred Barratt, the author of Physical Metempiric (1883), has been described as advocating panpsychism.

In 1893, Paul Carus proposed a philosophy similar to panpsychism, "panbiotism", according to which "everything is fraught with life; it contains life; it has the ability to live".

20th century

Bertrand Russell's neutral monist views tended toward panpsychism. The physicist Arthur Eddington also defended a form of panpsychism. The psychologists Gerard Heymans, James Ward and Charles Augustus Strong also endorsed variants of panpsychism.

In 1990, the physicist David Bohm published "A new theory of the relationship of mind and matter," a paper based on his interpretation of quantum mechanics. The philosopher Paavo Pylkkänen has described Bohm's view as a version of panprotopsychism.

One widespread misconception is that the arguably greatest systematic metaphysician of the 20th century, Alfred North Whitehead, was also panpsychism's most significant 20th century proponent. This misreading attributes to Whitehead an ontology according to which the basic nature of the world is made up of atomic mental events, termed "actual occasions". But rather than signifying such exotic metaphysical objects—which would in fact exemplify the fallacy of misplaced concreteness Whitehead criticizes—Whitehead's concept of "actual occasion" refers to the "immediate experienced occasion" of any possible perceiver, having in mind only himself as perceiver at the outset, in accordance with his strong commitment to radical empiricism.

Contemporary

Panpsychism has recently seen a resurgence in the philosophy of mind, set into motion by Thomas Nagel's 1979 article "Panpsychism" and further spurred by Galen Strawson's 2006 realistic monist article "Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism". Other recent proponents include American philosophers David Ray Griffin and David Skrbina, British philosophers Gregg Rosenberg, Timothy Sprigge, and Philip Goff, and Canadian philosopher William Seager. The British philosopher David Papineau, while distancing himself from orthodox panpsychists, has written that his view is "not unlike panpsychism" in that he rejects a line in nature between "events lit up by phenomenology [and] those that are mere darkness".

The integrated information theory of consciousness (IIT), proposed by the neuroscientist and psychiatrist Giulio Tononi in 2004 and since adopted by other neuroscientists such as Christof Koch, postulates that consciousness is widespread and can be found even in some simple systems.

In 2019, cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman published The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes. Hoffman argues that consensus reality lacks concrete existence, and is nothing more than an evolved user-interface. He argues that the true nature of reality is abstract "conscious agents". Science editor Annaka Harris argues that panpsychism is a viable theory in her 2019 book Conscious, though she stops short of fully endorsing it.

Panpsychism has been postulated by psychoanalyst Robin S. Brown as a means to theorizing relations between "inner" and "outer" tropes in the context of psychotherapy. Panpsychism has also been applied in environmental philosophy by Australian philosopher Freya Mathews, who has put forward the notion of ontopoetics as a version of panpsychism.

The geneticist Sewall Wright endorsed a version of panpsychism. He believed that consciousness is not a mysterious property emerging at a certain level of the hierarchy of increasing material complexity, but rather an inherent property, implying the most elementary particles have these properties.

Varieties

Panpsychism encompasses many theories, united only by the notion that mind in some form is ubiquitous.

Philosophical frameworks

Cosmopsychism

Cosmopsychism hypothesizes that the cosmos is a unified object that is ontologically prior to its parts. It has been described as an alternative to panpsychism, or as a form of panpsychism. Proponents of cosmopsychism claim that the cosmos as a whole is the fundamental level of reality and that it instantiates consciousness. They differ on that point from panpsychists, who usually claim that the smallest level of reality is fundamental and instantiates consciousness. Accordingly, human consciousness, for example, merely derives from a larger cosmic consciousness.

Panexperientialism

Panexperientialism is associated with the philosophies of, among others, Charles Hartshorne and Alfred North Whitehead, although the term itself was invented by David Ray Griffin to distinguish the process philosophical view from other varieties of panpsychism. Whitehead's process philosophy argues that the fundamental elements of the universe are "occasions of experience", which can together create something as complex as a human being. Building on Whitehead's work, process philosopher Michel Weber argues for a pancreativism. Goff has used the term panexperientialism more generally to refer to forms of panpsychism in which experience rather than thought is ubiquitous.

Panprotopsychism

Panprotopsychists believe that higher-order phenomenal properties (such as qualia) are logically entailed by protophenomenal properties, at least in principle. This is similar to how facts about H2O molecules logically entail facts about water: the lower-level facts are sufficient to explain the higher-order facts, since the former logically entail the latter. It also makes sense of questions about the unity of consciousness relating to the diversity of phenomenal experiences and the deflation of the self. Adherents of panprotopsychism believe that "protophenomenal" facts logically entail consciousness. Protophenomenal properties are usually picked out through a combination of functional and negative definitions: panphenomenal properties are those that logically entail phenomenal properties (a functional definition), which are themselves neither physical nor phenomenal (a negative definition).

Panprotopsychism is advertised as a solution to the combination problem: the problem of explaining how the consciousness of microscopic physical things might combine to give rise to the macroscopic consciousness of the whole brain. Because protophenomenal properties are by definition the constituent parts of consciousness, it is speculated that their existence would make the emergence of macroscopic minds less mysterious. The philosopher David Chalmers argues that the view faces difficulty with the combination problem. He considers it "ad hoc", and believes it diminishes the parsimony that made the theory initially interesting.

Russellian monism

Russellian monism is a type of neutral monism. The theory is attributed to Bertrand Russell, and may also be called Russell's panpsychism, or Russell's neutral monism. Russell believed that all causal properties are extrinsic manifestations of identical intrinsic properties. Russell called these identical internal properties quiddities. Just as the extrinsic properties of matter can form higher-order structure, so can their corresponding and identical quiddities. Russell believed the conscious mind was one such structure.

Religious or mystical ontologies

Advaita Vedānta

Advaita Vedānta is a form of idealism in Indian philosophy which views consensus reality as illusory. Anand Vaidya and Purushottama Bilimoria have argued that it can be considered a form of panpsychism or cosmopsychism.

Animism and hylozoism

Animism maintains that all things have a soul, and hylozoism maintains that all things are alive. Both could reasonably be interpreted as panpsychist, but both have fallen out of favour in contemporary academia. Modern panpsychists have tried to distance themselves from theories of this sort, careful to carve out the distinction between the ubiquity of experience and the ubiquity of mind and cognition.

Panpsychism and metempsychosis

Between 1840 and 1864, the Austrian mystic Jakob Lorber claimed to have received a 26-volume revelation. Various books of the Lorber Revelations say that specifica, closely resembling Leibniz's monads, form the most basic, irreducible substance of all physical and metaphysical creation. According to the Lorber Revelations, specifica grow in complexity and intelligence to form ever higher level clusters of intelligence until a fully intelligent human soul is reached. In this scenario panpsychism and metempsychosis are used to overcome the combination problem.

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature is an important and multifaceted doctrine in Mahayana Buddhism that is related to the capacity to attain Buddhahood. In numerous Indian sources, the idea is connected to the mind, especially the Buddhist concept of the luminous mind. In some Buddhist traditions, the Buddha-nature doctrine may be interpreted as implying a form of panpsychism. Graham Parks argues that most "traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean philosophy would qualify as panpsychist in nature".

The Huayan, Tiantai, and Tendai schools of Buddhism explicitly attribute Buddha-nature to inanimate objects such as lotus flowers and mountains. This idea was defended by figures such as the Tiantai patriarch Zhanran, who spoke of the Buddha-nature of grasses and trees. Similarly, Soto Zen master Dogen argued that "insentient beings expound" the teachings of the Buddha, and wrote about the "mind" (心, shin) of "fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles". The 9th-century Shingon figure Kukai went so far as to argue that natural objects such as rocks and stones are part of the supreme embodiment of the Buddha. According to Parks, Buddha-nature is best described "in western terms" as something "psychophysical".

Scientific theories

Conscious realism

It is a natural and near-universal assumption that the world has the properties and causal structures that we perceive it to have; to paraphrase Einstein's famous remark, we naturally assume that the moon is there whether anyone looks or not. Both theoretical and empirical considerations, however, increasingly indicate that this is not correct.

— Donald Hoffman, Conscious agent networks: Formal analysis and applications to cognition

Conscious realism is a theory proposed by Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist specialising in perception. He has written numerous papers on the topic which he summarised in his 2019 book The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes. Conscious realism builds upon Hoffman's former User-Interface Theory. In combination they argue that (1) consensus reality and spacetime are illusory, and are merely a "species specific evolved user interface"; (2) Reality is made of a complex, dimensionless, and timeless network of "conscious agents".

The consensus view is that perception is a reconstruction of one's environment. Hoffman views perception as a construction rather than a reconstruction. He argues that perceptual systems are analogous to information channels, and thus subject to data compression and reconstruction. The set of possible reconstructions for any given data set is quite large. Of that set, the subset that is homomorphic in relation to the original is minuscule, and does not necessarily—or, seemingly, even often—overlap with the subset that is efficient or easiest to use.

For example, consider a graph, such as a pie chart. A pie chart is easy to understand and use not because it is perfectly homomorphic with the data it represents, but because it is not. If a graph of, for example, the chemical composition of the human body were to look exactly like a human body, then we could not understand it. It is only because the graph abstracts away from the structure of its subject matter that it can be visualized. Alternatively, consider a graphical user interface on a computer. The reason graphical user interfaces are useful is that they abstract away from lower-level computational processes, such as machine code, or the physical state of a circuit-board. In general, it seems that data is most useful to us when it is abstracted from its original structure and repackaged in a way that is easier to understand, even if this comes at the cost of accuracy. Hoffman offers the "fitness beats truth theorem" as mathematical proof that perceptions of reality bear little resemblance to reality's true nature. From this he concludes that our senses do not faithfully represent the external world.

Even if reality is an illusion, Hoffman takes consciousness as an indisputable fact. He represents rudimentary units of consciousness (which he calls "conscious agents") as Markovian kernels. Though the theory was not initially panpsychist, he reports that he and his colleague Chetan Prakash found the math to be more parsimonious if it were. They hypothesize that reality is composed of these conscious agents, who interact to form "larger, more complex" networks.

Integrated information theory

Giulio Tononi first articulated Integrated information theory (IIT) in 2004, and it has undergone two major revisions since then. Tononi approaches consciousness from a scientific perspective, and has expressed frustration with philosophical theories of consciousness for lacking predictive power. Though integral to his theory, he refrains from philosophical terminology such as qualia or the unity of consciousness, instead opting for mathematically precise alternatives like entropy function and information integration. This has allowed Tononi to create a measurement for integrated information, which he calls phi (Φ). He believes consciousness is nothing but integrated information, so Φ measures consciousness. As it turns out, even basic objects or substances have a nonzero degree of Φ. This would mean that consciousness is ubiquitous, albeit to a minimal degree.

The philosopher Hedda Hassel Mørch's views IIT as similar to Russellian monism, while other philosophers, such as Chalmers and John Searle, consider it a form of panpsychism. IIT does not hold that all systems are conscious, leading Tononi and Koch to state that IIT incorporates some elements of panpsychism but not others. Koch has called IIT a "scientifically refined version" of panpsychism.

In relation to other theories

Because panpsychism encompasses a wide range of theories, it can in principle be compatible with reductive materialism, dualism, functionalism, or other perspectives depending on the details of a given formulation.

Dualism

David Chalmers and Philip Goff have each described panpsychism as an alternative to both materialism and dualism. Chalmers says panpsychism respects the conclusions of both the causal argument against dualism and the conceivability argument for dualism. Goff has argued that panpsychism avoids the disunity of dualism, under which mind and matter are ontologically separate, as well as dualism's problems explaining how mind and matter interact. By contrast, Uwe Meixner argues that panpsychism has dualist forms, which he contrasts to idealist forms.

Emergentism

Panpsychism is incompatible with emergentism. In general, theories of consciousness fall under one or the other umbrella; they hold either that consciousness is present at a fundamental level of reality (panpsychism) or that it emerges higher up (emergentism).

Idealism

There is disagreement over whether idealism is a form of panpsychism or a separate view. Both views hold that everything that exists has some form of experience. According to the philosophers William Seager and Sean Allen-Hermanson, "idealists are panpsychists by default". Charles Hartshorne contrasted panpsychism and idealism, saying that while idealists rejected the existence of the world observed with the senses or understood it as ideas within the mind of God, panpsychists accepted the reality of the world but saw it as composed of minds. Chalmers also contrasts panpsychism with idealism (as well as materialism and dualism). Meixner writes that formulations of panpsychism can be divided into dualist and idealist versions. He further divides the latter into "atomistic idealistic panpsychism", which he ascribes to David Hume, and "holistic idealistic panpsychism", which he favors.

Neutral monism

Neutral monism rejects the dichotomy of mind and matter, instead taking a third substance as fundamental that is neither mental nor physical. Proposals for the nature of the third substance have varied, with some theorists choosing to leave it undefined. This has led to a variety of formulations of neutral monism, which may overlap with other philosophies. In versions of neutral monism in which the world's fundamental constituents are neither mental nor physical, it is quite distinct from panpsychism. In versions where the fundamental constituents are both mental and physical, neutral monism may lead to panpsychism, panprotopsychism, or dual aspect theory.

In The Conscious Mind, David Chalmers writes that, in some instances, the differences between "Russell's neutral monism" and his property dualism are merely semantic. Philip Goff believes that neutral monism can reasonably be regarded as a form of panpsychism "in so far as it is a dual aspect view". Neutral monism, panpsychism, and dual aspect theory are grouped together or used interchangeably in some contexts.

Physicalism and materialism

Chalmers calls panpsychism an alternative to both materialism and dualism. Similarly, Goff calls panpsychism an alternative to both physicalism and substance dualism. Strawson, on the other hand, describes panpsychism as a form of physicalism, in his view the only viable form. Panpsychism can be combined with reductive materialism but cannot be combined with eliminative materialism because the latter denies the existence of the relevant mental attributes.

Arguments for

Hard problem of consciousness

But what consciousness is, we know not; and how it is that anything so remarkable as a state of consciousness comes about as the result of irritating nervous tissue, is just as unaccountable as the appearance of the Djin when Aladdin rubbed his lamp in the story, or as any other ultimate fact of nature.

— Thomas Henry Huxley (1896)

It evidently feels like something to be a human brain. This means that when things in the world are organised in a particular way, they begin to have an experience. The questions of why and how this material structure has experience, and why it has that particular experience rather than another experience, are known as the hard problem of consciousness. The term is attributed to Chalmers. He argues that even after "all the perceptual and cognitive functions within the vicinity of consciousness" are accounted for, "there may still remain a further unanswered question: Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience?"

Though Chalmers gave the hard problem of consciousness its present name, similar views were expressed before. Isaac Newton, John Locke, Gottfried Leibniz, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Henry Huxley, Wilhelm Wundt, all wrote about the seeming incompatibility of third-person functional descriptions of mind and matter and first-person conscious experience. Likewise, Asian philosophers like Dharmakirti and Guifeng Zongmi discussed the problem of how consciousness arises from unconscious matter. Similar sentiments have been articulated through philosophical inquiries such as the problem of other minds, solipsism, the explanatory gap, philosophical zombies, and Mary's room. These problems have caused Chalmers to consider panpsychism a viable solution to the hard problem, though he is not committed to any single view.

Brian Jonathan Garrett has compared the hard problem to vitalism, the now discredited hypothesis that life is inexplicable and can only be understood if some vital life force exists. He maintains that given time, consciousness and its evolutionary origins will be understood just as life is now understood. Daniel Dennett called the hard problem a "hunch", and maintained that conscious experience, as it is usually understood, is merely a complex cognitive illusion. Patricia Churchland, also an eliminative materialist, maintains that philosophers ought to be more patient: neuroscience is still in its early stages, so Chalmers's hard problem is premature. Clarity will come from learning more about the brain, not from metaphysical speculation.

Solutions

In The Conscious Mind (1996), Chalmers attempts to pinpoint why the hard problem is so hard. He concludes that consciousness is irreducible to lower-level physical facts, just as the fundamental laws of physics are irreducible to lower-level physical facts. Therefore, consciousness should be taken as fundamental in its own right and studied as such. Just as fundamental properties of reality are ubiquitous (even small objects have mass), consciousness may also be, though he considers that an open question.

In Mortal Questions (1979), Thomas Nagel argues that panpsychism follows from four premises:

- P1: There is no spiritual plane or disembodied soul; everything that exists is material.

- P2: Consciousness is irreducible to lower-level physical properties.

- P3: Consciousness exists.

- P4: Higher-order properties of matter (i.e., emergent properties) can, at least in principle, be reduced to their lower-level properties.

Before the first premise is accepted, the range of possible explanations for consciousness is fully open. Each premise, if accepted, narrows down that range of possibilities. If the argument is sound, then by the last premise panpsychism is the only possibility left.

- If (P1) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it exists within the physical world.

- If (P2) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it (a) exists as distinct property of matter or (b) is fundamentally entailed by matter.

- If (P3) is true, then consciousness exists, and is either (a) its own property of matter or (b) composed by the matter of the brain but not logically entailed by it.

- If (P4) is true, then (b) is false, and consciousness must be its own unique property of matter.

Therefore, if all four premises are true, consciousness is its own unique property of matter and panpsychism is true.

Mind-body problem

Dualism makes the problem insoluble; materialism denies the existence of any phenomenon to study, and hence of any problem.

— John R. Searle, Consciousness and Language, p. 47

In 2015, Chalmers proposed a possible solution to the mind-body problem through the argumentative format of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The goal of such arguments is to argue for sides of a debate (the thesis and antithesis), weigh their vices and merits, and then reconcile them (the synthesis). Chalmers's thesis, antithesis, and synthesis are as follows:

- Thesis: materialism is true; everything is fundamentally physical.

- Antithesis: dualism is true; not everything is fundamentally physical.

- Synthesis: panpsychism is true.

(1) A centerpiece of Chalmers's argument is the physical world's causal closure. Newton's law of motion explains this phenomenon succinctly: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Cause and effect is a symmetrical process. There is no room for consciousness to exert any causal power on the physical world unless it is itself physical.

(2) On one hand, if consciousness is separate from the physical world then there is no room for it to exert any causal power on the world (a state of affairs philosophers call epiphenomenalism). If consciousness plays no causal role, then it is unclear how Chalmers could even write this paper. On the other hand, consciousness is irreducible to the physical processes of the brain.

(3) Panpsychism has all the benefits of materialism because it could mean that consciousness is physical while also escaping the grasp of epiphenomenalism. After some argumentation Chalmers narrows it down further to Russellian monism, concluding that thoughts, actions, intentions and emotions may just be the quiddities of neurotransmitters, neurons, and glial cells.

Problem of substance

Physics is mathematical, not because we know so much about the physical world, but because we know so little: it is only its mathematical properties that we can discover. For the rest our knowledge is negative.

— Bertrand Russell, An Outline of Philosophy (1927)

Rather than solely trying to solve the problem of consciousness, Russell also attempted to solve the problem of substance, which is arguably a form of the problem of infinite regress.

(1) Like many sciences, physics describes the world through mathematics. Unlike other sciences, physics cannot describe what Schopenhauer called the "object that grounds" mathematics. Economics is grounded in resources being allocated, and population dynamics is grounded in individual people within that population. The objects that ground physics, however, can be described only through more mathematics. In Russell's words, physics describes "certain equations giving abstract properties of their changes". When it comes to describing "what it is that changes, and what it changes from and to—as to this, physics is silent". In other words, physics describes matter's extrinsic properties, but not the intrinsic properties that ground them.

(2) Russell argued that physics is mathematical because "it is only mathematical properties we can discover". This is true almost by definition: if only extrinsic properties are outwardly observable, then they will be the only ones discovered. This led Alfred North Whitehead to conclude that intrinsic properties are "intrinsically unknowable".

(3) Consciousness has many similarities to these intrinsic properties of physics. It, too, cannot be directly observed from an outside perspective. And it, too, seems to ground many observable extrinsic properties: presumably, music is enjoyable because of the experience of listening to it, and chronic pain is avoided because of the experience of pain, etc. Russell concluded that consciousness must be related to these extrinsic properties of matter. He called these intrinsic properties quiddities. Just as extrinsic physical properties can create structures, so can their corresponding and identical quiddites. The conscious mind, Russell argued, is one such structure.

Proponents of panpsychism who use this line of reasoning include Chalmers, Annaka Harris, and Galen Strawson. Chalmers has argued that the extrinsic properties of physics must have corresponding intrinsic properties; otherwise the universe would be "a giant causal flux" with nothing for "causation to relate", which he deems a logical impossibility. He sees consciousness as a promising candidate for that role. Galen Strawson calls Russell's panpsychism "realistic physicalism". He argues that "the experiential considered specifically as such" is what it means for something to be physical. Just as mass is energy, Strawson believes that consciousness "just is" matter.

Max Tegmark, theoretical physicist and creator of the mathematical universe hypothesis, disagrees with these conclusions. By his account, the universe is not just describable by math but is math; comparing physics to economics or population dynamics is a disanalogy. While population dynamics may be grounded in individual people, those people are grounded in "purely mathematical objects" such as energy and charge. The universe is, in a fundamental sense, made of nothing.

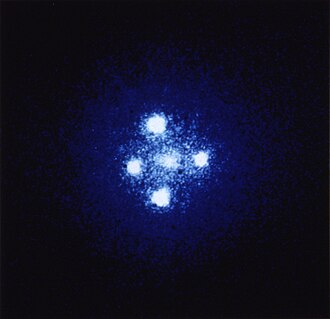

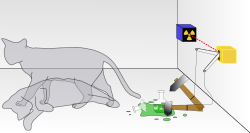

Quantum mechanics

In a 2018 interview, Chalmers called quantum mechanics "a magnet for anyone who wants to find room for crazy properties of the mind", but not entirely without warrant. The relationship between observation (and, by extension, consciousness) and the wave-function collapse is known as the measurement problem. It seems that atoms, photons, etc. are in quantum superposition (which is to say, in many seemingly contradictory states or locations simultaneously) until measured in some way. This process is known as a wave-function collapse. According to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, one of the oldest interpretations and the most widely taught, it is the act of observation that collapses the wave-function. Erwin Schrödinger famously articulated the Copenhagen interpretation's unusual implications in the thought experiment now known as Schrödinger's cat. He imagines a box that contains a cat, a flask of poison, radioactive material, and a Geiger counter. The apparatus is configured so that when the Geiger counter detects radioactive decay, the flask will shatter, poisoning the cat. Unless and until the Geiger counter detects the radioactive decay of a single atom, the cat survives. The radioactive decay the Geiger counter detects is a quantum event; each decay corresponds to a quantum state transition of a single atom of the radioactive material. According to Schrödinger's wave equation, until they are observed, quantum particles, including the atoms of the radioactive material, are in quantum state superposition; each unmeasured atom in the radioactive material is in a quantum superposition of decayed and not decayed. This means that while the box remains sealed and its contents unobserved, the Geiger counter is also in a superposition of states of decay detected and no decay detected; the vial is in a superposition of both shattered and not shattered and the cat in a superposition of dead and alive. But when the box is unsealed, the observer finds a cat that is either dead or alive; there is no superposition of states. Since the cat is no longer in a superposition of states, then neither is the radioactive atom (nor the vial or the Geiger counter). Hence Schrödinger's wave function no longer holds and the wave function that described the atom—and its superposition of states—is said to have "collapsed": the atom now has only a single state, corresponding to the cat's observed state. But until an observer opens the box and thereby causes the wave function to collapse, the cat is both dead and alive. This has raised questions about, in John S. Bell's words, "where the observer begins and ends".

The measurement problem has largely been characterised as the clash of classical physics and quantum mechanics. Bohm argued that it is rather a clash of classical physics, quantum mechanics, and phenomenology; all three levels of description seem to be difficult to reconcile, or even contradictory. Though not referring specifically to quantum mechanics, Chalmers has written that if a theory of everything is ever discovered, it will be a set of "psychophysical laws", rather than simply a set of physical laws. With Chalmers as their inspiration, Bohm and Pylkkänen set out to do just that in their panprotopsychism. Chalmers, who is critical of the Copenhagen interpretation and most quantum theories of consciousness, has coined this "the Law of the Minimisation of Mystery".

The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics does not take observation as central to the wave-function collapse, because it denies that the collapse happens. On the many-worlds interpretation, just as the cat is both dead and alive, the observer both sees a dead cat and sees a living cat. Even though observation does not play a central role in this case, questions about observation are still relevant to the discussion. In Roger Penrose's words:

I do not see why a conscious being need be aware of only "one" of the alternatives in a linear superposition. What is it about consciousnesses that says that consciousness must not be "aware" of that tantalising linear combination of both a dead and a live cat? It seems to me that a theory of consciousness would be needed for one to square the many world view with what one actually observes.

Chalmers believes that the tentative variant of panpsychism outlined in The Conscious Mind (1996) does just that. Leaning toward the many-worlds interpretation due to its mathematical parsimony, he believes his variety of panpsychist property dualism may be the theory Penrose is seeking. Chalmers believes that information will play an integral role in any theory of consciousness because the mind and brain have corresponding informational structures. He considers the computational nature of physics further evidence of information's central role, and suggests that information that is physically realised is simultaneously phenomenally realised; both regularities in nature and conscious experience are expressions of information's underlying character. The theory implies panpsychism, and also solves the problem Penrose poses. On Chalmers's formulation, information in any given position is phenomenally realised, whereas the informational state of the superposition as a whole is not. Panpsychist interpretations of quantum mechanics have been put forward by such philosophers as Whitehead, Shan Gao, Michael Lockwood, and Hoffman, who is a cognitive scientist. Protopanpsychist interpretations have been put forward by Bohm and Pylkkänen.

Tegmark has formally calculated the "decoherence rates" of neurons, finding that the brain is a "classical rather than a quantum system" and that quantum mechanics does not relate "to consciousness in any fundamental way". Hagan et al. criticize Tegmark's estimate and present a revised calculation that yields a range of decoherence rates within the realm of physiological relevance.

In 2007, Steven Pinker criticized explanations of consciousness invoking quantum physics, saying: "to my ear, this amounts to the feeling that quantum mechanics sure is weird, and consciousness sure is weird, so maybe quantum mechanics can explain consciousness"; a view echoed by physicist Stephen Hawking. In 2017, Penrose rejected these characterizations, stating that disagreements are about the nature of quantum mechanics.

Arguments against

Theoretical issues

One criticism of panpsychism is that it cannot be empirically tested. A corollary of this criticism is that panpsychism has no predictive power. Tononi and Koch write: "Besides claiming that matter and mind are one thing, [panpsychism] has little constructive to say and offers no positive laws explaining how the mind is organized and works".

John Searle has alleged that panpsychism's unfalsifiability goes deeper than run-of-the-mill untestability: it is unfalsifiable because "It does not get up to the level of being false. It is strictly speaking meaningless because no clear notion has been given to the claim". The need for coherence and clarification is accepted by David Skrbina, a proponent of panpsychism.

Many proponents of panpsychism base their arguments not on empirical support but on panpsychism's theoretical virtues. Chalmers says that while no direct evidence exists for the theory, neither is there direct evidence against it, and that "there are indirect reasons, of a broadly theoretical character, for taking the view seriously". Notwithstanding Tononi and Koch's criticism of panpsychism, they state that it integrates consciousness into the physical world in a way that is "elegantly unitary".

A related criticism is what seems to many to be the theory's bizarre nature. Goff dismisses this objection: though he admits that panpsychism is counterintuitive, he argues that Einstein's and Darwin's theories are also counterintuitive. "At the end of the day," he writes, "you should judge a view not for its cultural associations but by its explanatory power".

Problem of mental causation

Philosophers such as Chalmers have argued that theories of consciousness should be capable of providing insight into the brain and mind to avoid the problem of mental causation. If they fail to do that, the theory will succumb to epiphenomenalism, a view commonly criticised as implausible or even self-contradictory. Proponents of panpsychism (especially those with neutral monist tendencies) hope to bypass this problem by dismissing it as a false dichotomy; mind and matter are two sides of the same coin, and mental causation is merely the extrinsic description of intrinsic properties of mind. Robert Howell has argued that all causal functions are still accounted for dispositionally (i.e., in terms of the behaviors described by science), leaving phenomenality causally inert. He concludes, "This leaves us once again with epiphenomenal qualia, only in a very surprising place". Neutral monists reject such dichotomous views of mind-body interaction.

Combination problem

The combination problem (which is related to the binding problem) can be traced to William James, but was given its present name by William Seager in 1995. The problem arises from the tension between the seemingly irreducible nature of consciousness and its ubiquity. If consciousness is ubiquitous, then in panpsychism, every atom (or every bit, depending on the version of panpsychism) has a minimal level of it. How then, as Keith Frankish puts it, do these "tiny consciousnesses combine" to create larger conscious experiences such as "the twinge of pain" he feels in his knee? This objection has garnered significant attention, and many have attempted to answer it. None of the proposed answers has gained widespread acceptance.

Concepts related to this problem include the classical sorites paradox (aggregates and organic wholes), mereology (the philosophical study of parts and wholes), Gestalt psychology, and Leibniz's concept of the vinculum substantiale.