The Three Gorges Dam in Central China is the world's largest power producing facility of any kind.

Hydroelectricity is electricity produced from hydropower. In 2015, hydropower generated 16.6% of the world's total electricity and 70% of all renewable electricity, and was expected to increase about 3.1% each year for the next 25 years.

Hydropower is produced in 150 countries, with the Asia-Pacific region generating 33 percent of global hydropower in 2013. China

is the largest hydroelectricity producer, with 920 TWh of production in

2013, representing 16.9 percent of domestic electricity use.

The cost of hydroelectricity is relatively low, making it a

competitive source of renewable electricity. The hydro station consumes

no water, unlike coal or gas plants. The average cost of electricity

from a hydro station larger than 10 megawatts is 3 to 5 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour.

With a dam and reservoir it is also a flexible source of electricity

since the amount produced by the station can be varied up or down very

rapidly (as little as a few seconds) to adapt to changing energy

demands. Once a hydroelectric complex is constructed, the project

produces no direct waste, and in many cases, has a considerably lower

output level of greenhouse gases than fossil fuel powered energy plants.

History

Museum Hydroelectric power plant ″Under the Town″ in Serbia, built in 1900.

Hydropower has been used since ancient times to grind flour and perform other tasks. In the mid-1770s, French engineer Bernard Forest de Bélidor published Architecture Hydraulique which described vertical- and horizontal-axis hydraulic machines. By the late 19th century, the electrical generator was developed and could now be coupled with hydraulics. The growing demand for the Industrial Revolution would drive development as well. In 1878 the world's first hydroelectric power scheme was developed at Cragside in Northumberland, England by William Armstrong. It was used to power a single arc lamp in his art gallery. The old Schoelkopf Power Station No. 1 near Niagara Falls in the U.S. side began to produce electricity in 1881. The first Edison hydroelectric power station, the Vulcan Street Plant, began operating September 30, 1882, in Appleton, Wisconsin, with an output of about 12.5 kilowatts. By 1886 there were 45 hydroelectric power stations in the U.S. and Canada. By 1889 there were 200 in the U.S. alone.

The Warwick Castle water-powered generator house, used for the generation of electricity for the castle from 1894 until 1940

At the beginning of the 20th century, many small hydroelectric power

stations were being constructed by commercial companies in mountains

near metropolitan areas. Grenoble, France held the International Exhibition of Hydropower and Tourism with over one million visitors. By 1920 as 40% of the power produced in the United States was hydroelectric, the Federal Power Act was enacted into law. The Act created the Federal Power Commission

to regulate hydroelectric power stations on federal land and water. As

the power stations became larger, their associated dams developed

additional purposes to include flood control, irrigation and navigation. Federal funding became necessary for large-scale development and federally owned corporations, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933) and the Bonneville Power Administration (1937) were created. Additionally, the Bureau of Reclamation

which had begun a series of western U.S. irrigation projects in the

early 20th century was now constructing large hydroelectric projects

such as the 1928 Hoover Dam. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was also involved in hydroelectric development, completing the Bonneville Dam in 1937 and being recognized by the Flood Control Act of 1936 as the premier federal flood control agency.

Hydroelectric power stations continued to become larger throughout the 20th century. Hydropower was referred to as white coal for its power and plenty. Hoover Dam's initial 1,345 MW power station was the world's largest hydroelectric power station in 1936; it was eclipsed by the 6809 MW Grand Coulee Dam in 1942. The Itaipu Dam opened in 1984 in South America as the largest, producing 14,000 MW but was surpassed in 2008 by the Three Gorges Dam in China at 22,500 MW. Hydroelectricity would eventually supply some countries, including Norway, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Paraguay and Brazil,

with over 85% of their electricity. The United States currently has

over 2,000 hydroelectric power stations that supply 6.4% of its total

electrical production output, which is 49% of its renewable electricity.

Future potential

The technical potential for hydropower development around the world

is much greater than the actual production: the percent of potential

hydropower capacity that has not been developed is 71% in Europe, 75% in

North America, 79% in South America, 95% in Africa, 95% in the Middle

East, and 82% in Asia-Pacific.

The political realities of new reservoirs in western countries, economic

limitations in the third world and the lack of a transmission system in

undeveloped areas result in the possibility of developing 25% of the

remaining technically exploitable potential before 2050, with the bulk

of that being in the Asia-Pacific area. Some countries have highly

developed their hydropower potential and have very little room for

growth: Switzerland produces 88% of its potential and Mexico 80%.

Generating methods

Turbine row at El Nihuil II Power Station in Mendoza, Argentina

An old turbine runner on display at the Glen Canyon Dam

Cross section of a conventional hydroelectric dam.

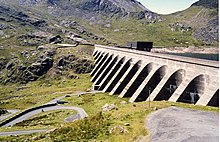

Conventional dams

Most hydroelectric power comes from the potential energy of dammed water driving a water turbine and generator.

The power extracted from the water depends on the volume and on the

difference in height between the source and the water's outflow. This

height difference is called the head. A large pipe (the "penstock") delivers water from the reservoir to the turbine.

Pumped-storage

This method produces electricity to supply high peak demands by moving water between reservoirs

at different elevations. At times of low electrical demand, the excess

generation capacity is used to pump water into the higher reservoir.

When the demand becomes greater, water is released back into the lower

reservoir through a turbine. Pumped-storage schemes currently provide

the most commercially important means of large-scale grid energy storage and improve the daily capacity factor of the generation system. Pumped storage is not an energy source, and appears as a negative number in listings.

Run-of-the-river

Run-of-the-river hydroelectric stations are those with small or no

reservoir capacity, so that only the water coming from upstream is

available for generation at that moment, and any oversupply must pass

unused. A constant supply of water from a lake or existing reservoir

upstream is a significant advantage in choosing sites for

run-of-the-river. In the United States, run of the river hydropower

could potentially provide 60,000 megawatts (80,000,000 hp) (about 13.7%

of total use in 2011 if continuously available).

Tide

A tidal power

station makes use of the daily rise and fall of ocean water due to

tides; such sources are highly predictable, and if conditions permit

construction of reservoirs, can also be dispatchable to generate power during high demand periods. Less common types of hydro schemes use water's kinetic energy or undammed sources such as undershot water wheels.

Tidal power is viable in a relatively small number of locations around

the world. In Great Britain, there are eight sites that could be

developed, which

have the potential to generate 20% of the electricity used in 2012.

Sizes, types and capacities of hydroelectric facilities

Large facilities

Large-scale hydroelectric power stations are more commonly seen as

the largest power producing facilities in the world, with some

hydroelectric facilities capable of generating more than double the

installed capacities of the current largest nuclear power stations.

Although no official definition exists for the capacity range of

large hydroelectric power stations, facilities from over a few hundred megawatts are generally considered large hydroelectric facilities.

| Rank | Station | Country | Location | (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Three Gorges Dam | 30°49′15″N 111°00′08″E | 22,500 | |

| 2. | Itaipu Dam | 25°24′31″S 54°35′21″W | 14,000 | |

| 3. | Xiluodu Dam | 28°15′35″N 103°38′58″E | 13,860 | |

| 4. | Guri Dam | 07°45′59″N 62°59′57″W | 10,200 |

Small

Small hydro is the development of hydroelectric power

on a scale serving a small community or industrial plant. The

definition of a small hydro project varies but a generating capacity of

up to 10 megawatts (MW) is generally accepted as the upper limit of what can be termed small hydro. This may be stretched to 25 MW and 30 MW in Canada and the United States. Small-scale hydroelectricity production grew by 29% from 2005 to 2008, raising the total world small-hydro capacity to 85 GW. Over 70% of this was in China (65 GW), followed by Japan (3.5 GW), the United States (3 GW), and India (2 GW).

A micro-hydro facility in Vietnam

Pico hydroelectricity in Mondulkiri, Cambodia

Small hydro stations may be connected to conventional electrical

distribution networks as a source of low-cost renewable energy.

Alternatively, small hydro projects may be built in isolated areas that

would be uneconomic to serve from a network, or in areas where there is

no national electrical distribution network. Since small hydro projects

usually have minimal reservoirs and civil construction work, they are

seen as having a relatively low environmental impact compared to large

hydro. This decreased environmental impact depends strongly on the

balance between stream flow and power production.

Micro

Micro hydro is a term used for hydroelectric power installations that typically produce up to 100 kW

of power. These installations can provide power to an isolated home or

small community, or are sometimes connected to electric power networks.

There are many of these installations around the world, particularly in

developing nations as they can provide an economical source of energy

without purchase of fuel. Micro hydro systems complement photovoltaic

solar energy systems because in many areas, water flow, and thus

available hydro power, is highest in the winter when solar energy is at a

minimum.

Pico

Pico hydro is a term used for hydroelectric power generation of under 5 kW.

It is useful in small, remote communities that require only a small

amount of electricity. For example, to power one or two fluorescent

light bulbs and a TV or radio for a few homes.

Even smaller turbines of 200-300W may power a single home in a

developing country with a drop of only 1 m (3 ft). A Pico-hydro setup is

typically run-of-the-river,

meaning that dams are not used, but rather pipes divert some of the

flow, drop this down a gradient, and through the turbine before

returning it to the stream.

Underground

An underground power station

is generally used at large facilities and makes use of a large natural

height difference between two waterways, such as a waterfall or mountain

lake. An underground tunnel is constructed to take water from the high

reservoir to the generating hall built in an underground cavern near the

lowest point of the water tunnel and a horizontal tailrace taking water

away to the lower outlet waterway.

Measurement of the tailrace and forebay rates at the Limestone Generating Station in Manitoba, Canada.

Calculating available power

A simple formula for approximating electric power production at a hydroelectric station is:

where

- is power (in watts)

- ("eta") is the coefficient of efficiency (a unitless, scalar coefficient, ranging from 0 for completely inefficient to 1 for completely efficient).

- ("rho") is the density of water (~1000 kg/m3)

- is the volumetric flow rate (in m3/s)

- is the mass flow rate (in kg/s)

- ("Delta h") is the change in height (in meters)

- is acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m/s2)

Efficiency is often higher (that is, closer to 1) with larger and

more modern turbines. Annual electric energy production depends on the

available water supply. In some installations, the water flow rate can

vary by a factor of 10:1 over the course of a year.

Properties

Advantages

The Ffestiniog Power Station can generate 360 MW of electricity within 60 seconds of the demand arising.

Flexibility

Hydropower is a flexible source of electricity since stations can be

ramped up and down very quickly to adapt to changing energy demands. Hydro turbines have a start-up time of the order of a few minutes.

It takes around 60 to 90 seconds to bring a unit from cold start-up to

full load; this is much shorter than for gas turbines or steam plants. Power generation can also be decreased quickly when there is a surplus power generation.

Hence the limited capacity of hydropower units is not generally used to

produce base power except for vacating the flood pool or meeting

downstream needs. Instead, it can serve as backup for non-hydro generators.

Low cost/high value power

The major advantage of conventional hydroelectric dams with reservoirs is their ability to store water at low cost for dispatch later

as high value clean electricity. The average cost of electricity from a

hydro station larger than 10 megawatts is 3 to 5 U.S. cents per

kilowatt-hour.

When used as peak power to meet demand, hydroelectricity has a higher

value than base power and a much higher value compared to intermittent energy sources.

Hydroelectric stations have long economic lives, with some plants still in service after 50–100 years. Operating labor cost is also usually low, as plants are automated and have few personnel on site during normal operation.

Where a dam serves multiple purposes, a hydroelectric station may

be added with relatively low construction cost, providing a useful

revenue stream to offset the costs of dam operation. It has been

calculated that the sale of electricity from the Three Gorges Dam will cover the construction costs after 5 to 8 years of full generation.

However, some data shows that in most countries large hydropower dams

will be too costly and take too long to build to deliver a positive risk

adjusted return, unless appropriate risk management measures are put in

place.

Suitability for industrial applications

While many hydroelectric projects supply public electricity networks, some are created to serve specific industrial enterprises. Dedicated hydroelectric projects are often built to provide the substantial amounts of electricity needed for aluminium electrolytic plants, for example. The Grand Coulee Dam switched to support Alcoa aluminium in Bellingham, Washington, United States for American World War II airplanes before it was allowed to provide irrigation and power to citizens (in addition to aluminium power) after the war. In Suriname, the Brokopondo Reservoir was constructed to provide electricity for the Alcoa aluminium industry. New Zealand's Manapouri Power Station was constructed to supply electricity to the aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point.

Reduced CO2 emissions

Since hydroelectric dams do not use fuel, power generation does not produce carbon dioxide.

While carbon dioxide is initially produced during construction of the

project, and some methane is given off annually by reservoirs, hydro

generally has the lowest life cycle greenhouse gas emissions for power generation.

Compared to fossil fuels generating an equivalent amount of

electricity, hydro displaced three billion tonnes of CO2 emissions in

2011. According to a comparative study by the Paul Scherrer Institute and the University of Stuttgart, hydroelectricity in Europe produces the least amount of greenhouse gases and externality of any energy source. Coming in second place was wind, third was nuclear energy, and fourth was solar photovoltaic. The low greenhouse gas impact of hydroelectricity is found especially in temperate climates.

Greater greenhouse gas emission impacts are found in the tropical

regions because the reservoirs of power stations in tropical regions

produce a larger amount of methane than those in temperate areas.

Like other non-fossil fuel sources, hydropower also has no emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, or other particulates.

Other uses of the reservoir

Reservoirs created by hydroelectric schemes often provide facilities for water sports, and become tourist attractions themselves. In some countries, aquaculture in reservoirs is common. Multi-use dams installed for irrigation support agriculture

with a relatively constant water supply. Large hydro dams can control

floods, which would otherwise affect people living downstream of the

project.

Disadvantages

Ecosystem damage and loss of land

Merowe Dam in Sudan. Hydroelectric power stations that use dams submerge large areas of land due to the requirement of a reservoir. These changes to land color or albedo,

alongside certain projects that concurrently submerge rainforests, can

in these specific cases result in the global warming impact, or

equivalent life-cycle greenhouse gases of hydroelectricity projects, to potentially exceed that of coal power stations.

Large reservoirs associated with traditional hydroelectric power

stations result in submersion of extensive areas upstream of the dams,

sometimes destroying biologically rich and productive lowland and

riverine valley forests, marshland and grasslands. Damming interrupts

the flow of rivers and can harm local ecosystems, and building large

dams and reservoirs often involves displacing people and wildlife. The loss of land is often exacerbated by habitat fragmentation of surrounding areas caused by the reservoir.

Hydroelectric projects can be disruptive to surrounding aquatic ecosystems

both upstream and downstream of the plant site. Generation of

hydroelectric power changes the downstream river environment. Water

exiting a turbine usually contains very little suspended sediment, which

can lead to scouring of river beds and loss of riverbanks. Since turbine gates are often opened intermittently, rapid or even daily fluctuations in river flow are observed.

Water loss by evaporation

A 2011 study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory

concluded that hydroelectric plants in the U.S. consumed between 1,425

and 18,000 gallons of water per megawatt-hour (gal/MWh) of electricity

generated, through evaporation losses in the reservoir. The median loss

was 4,491 gal/MWh, which is higher than the loss for generation

technologies that use cooling towers, including concentrating solar

power (865 gal/MWh for CSP trough, 786 gal/MWh for CSP tower), coal (687

gal/MWh), nuclear (672 gal/MWh), and natural gas (198 gal/MWh). Where

there are multiple uses of reservoirs such as water supply, recreation,

and flood control, all reservoir evaporation is attributed to power

production.

Siltation and flow shortage

When water flows it has the ability to transport particles heavier

than itself downstream. This has a negative effect on dams and

subsequently their power stations, particularly those on rivers or

within catchment areas with high siltation. Siltation

can fill a reservoir and reduce its capacity to control floods along

with causing additional horizontal pressure on the upstream portion of

the dam. Eventually, some reservoirs can become full of sediment and

useless or over-top during a flood and fail.

Changes in the amount of river flow will correlate with the

amount of energy produced by a dam. Lower river flows will reduce the

amount of live storage in a reservoir therefore reducing the amount of

water that can be used for hydroelectricity. The result of diminished

river flow can be power shortages in areas that depend heavily on

hydroelectric power. The risk of flow shortage may increase as a result

of climate change. One study from the Colorado River

in the United States suggest that modest climate changes, such as an

increase in temperature in 2 degree Celsius resulting in a 10% decline

in precipitation, might reduce river run-off by up to 40%. Brazil

in particular is vulnerable due to its heavy reliance on

hydroelectricity, as increasing temperatures, lower water flow and

alterations in the rainfall regime, could reduce total energy production

by 7% annually by the end of the century.

Methane emissions (from reservoirs)

The Hoover Dam in the United States is a large conventional dammed-hydro facility, with an installed capacity of 2,080 MW.

Lower positive impacts are found in the tropical regions, as it has

been noted that the reservoirs of power plants in tropical regions

produce substantial amounts of methane. This is due to plant material in flooded areas decaying in an anaerobic environment and forming methane, a greenhouse gas. According to the World Commission on Dams report,

where the reservoir is large compared to the generating capacity (less

than 100 watts per square metre of surface area) and no clearing of the

forests in the area was undertaken prior to impoundment of the

reservoir, greenhouse gas emissions from the reservoir may be higher

than those of a conventional oil-fired thermal generation plant.

In boreal reservoirs of Canada and Northern Europe, however, greenhouse gas emissions

are typically only 2% to 8% of any kind of conventional fossil-fuel

thermal generation. A new class of underwater logging operation that

targets drowned forests can mitigate the effect of forest decay.

Relocation

Another disadvantage of hydroelectric dams is the need to relocate

the people living where the reservoirs are planned. In 2000, the World

Commission on Dams estimated that dams had physically displaced 40-80

million people worldwide.

Failure risks

Because large conventional dammed-hydro facilities hold back large

volumes of water, a failure due to poor construction, natural disasters

or sabotage can be catastrophic to downriver settlements and

infrastructure.

During Typhoon Nina in 1975 Banqiao Dam

failed in Southern China when more than a year's worth of rain fell

within 24 hours. The resulting flood resulted in the deaths of 26,000

people, and another 145,000 from epidemics. Millions were left homeless.

The creation of a dam in a geologically inappropriate location may cause disasters such as 1963 disaster at Vajont Dam in Italy, where almost 2,000 people died.

The Malpasset Dam failure in Fréjus on the French Riviera (Côte d'Azur), southern France, collapsed on December 2, 1959, killing 423 people in the resulting flood.

Smaller dams and micro hydro

facilities create less risk, but can form continuing hazards even after

being decommissioned. For example, the small earthen embankment Kelly Barnes Dam failed in 1977, twenty years after its power station was decommissioned, causing 39 deaths.

Comparison and interactions with other methods of power generation

Hydroelectricity eliminates the flue gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion, including pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, dust, and mercury in the coal. Hydroelectricity also avoids the hazards of coal mining and the indirect health effects of coal emissions.

Nuclear power

Compared to nuclear power,

hydroelectricity construction requires altering large areas of the

environment while a nuclear power station has a small footprint, and

hydro-powerstation failures have caused tens of thousands of more deaths

than any nuclear station failure. The creation of Garrison Dam,

for example, required Native American land to create Lake Sakakawea,

which has a shoreline of 1,320 miles, and caused the inhabitants to sell

94% of their arable land for $7.5 million in 1949.

However, nuclear power is relatively inflexible; although nuclear

power can reduce its output reasonably quickly. Since the cost of

nuclear power is dominated by its high infrastructure costs, the cost

per unit energy goes up significantly with low production. Because of

this, nuclear power is mostly used for baseload.

By way of contrast, hydroelectricity can supply peak power at much

lower cost. Hydroelectricity is thus often used to complement nuclear or

other sources for load following. Country examples were they are paired in a close to 50/50 share include the electric grid in Switzerland, the Electricity sector in Sweden and to a lesser extent, Ukraine and the Electricity sector in Finland.

Wind power

Wind power goes through predictable variation by season, but is intermittent

on a daily basis. Maximum wind generation has little relationship to

peak daily electricity consumption, the wind may peak at night when

power isn't needed or be still during the day when electrical demand is

highest. Occasionally weather patterns can result in low wind for days

or weeks at a time, a hydroelectric reservoir capable of storing weeks

of output is useful to balance generation on the grid. Peak wind power

can be offset by minimum hydropower and minimum wind can be offset with

maximum hydropower. In this way the easily regulated character of

hydroelectricity is used to compensate for the intermittent nature of

wind power. Conversely, in some cases wind power can be used to spare

water for later use in dry seasons.

In areas that do not have hydropower, pumped storage serves a similar role, but at a much higher cost and 20% lower efficiency. An example of this is Norway's trading with Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and possibly Germany or the UK in the future. Norway is 98% hydropower, while it's flatland neighbors are installing wind power.

World hydroelectric capacity

World renewable energy share (2008)

Trends in the top five hydroelectricity-producing countries

The ranking of hydro-electric capacity is either by actual annual

energy production or by installed capacity power rating. In 2015

hydropower generated 16.6% of the worlds total electricity and 70% of

all renewable electricity.

Hydropower is produced in 150 countries, with the Asia-Pacific region

generated 32 percent of global hydropower in 2010. China is the largest

hydroelectricity producer, with 721 terawatt-hours of production in

2010, representing around 17 percent of domestic electricity use. Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Austria, Switzerland, Venezuela, and several other countries have a majority of the internal electric energy production from hydroelectric power. Paraguay produces 100% of its electricity from hydroelectric dams and exports 90% of its production to Brazil and to Argentina. Norway produces 96% of its electricity from hydroelectric sources.

A hydro-electric station rarely operates at its full power rating

over a full year; the ratio between annual average power and installed

capacity rating is the capacity factor. The installed capacity is the sum of all generator nameplate power ratings.