Etymology

The term 'lucid dream' was coined by Dutch author and psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden in his 1913 article A Study of Dreams,

though descriptions of dreamers being aware that they are dreaming

predates the actual term. Frederik Van Eeden studied his personal dreams

since 1896. He wrote down the most interesting ones, and, out of all

these dreams, 352 were what we know now as “lucid dreams”. Throughout

all the data he collected from dreaming, he created different names for

different types of dreams. He named 7 different types of dreams: initial

dreams, pathological, ordinary dreaming, vivid dreaming, demoniacal,

general dream-sensations, and lucid dreaming. Frederick Van Eeden said

the seventh type of dreaming, lucid dreaming, was the most interesting

and worthy of the most careful observation of studies. Eeden studied

lucid dreaming between January 20, 1898, and December 26, 1912. In this

state of dreaming Eeden explains that you are completely aware of your

surroundings and are able to direct your actions freely, yet the sleep

is stimulating and uninterrupted.

History

Ancient

Early references to the phenomenon are found in ancient Greek writing. For example, the philosopher Aristotle

wrote: 'often when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness

which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream'. Meanwhile, the physician Galen of Pergamon used lucid dreams as a form of therapy. In addition, a letter written by Saint Augustine of Hippo in 415 AD tells the story of a dreamer, Doctor Gennadius, and refers to lucid dreaming.

Zhuangzi dreaming of a butterfly

In Eastern thought, cultivating the dreamer's ability to be aware

that he or she is dreaming is central to both the Tibetan Buddhist

practice of dream Yoga, and the ancient Indian Hindu practice of Yoga nidra. The cultivation of such awareness was common practice among early Buddhists.

17th century

Philosopher and physician Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) was fascinated by dreams and described his own ability to lucid dream in his Religio Medici,

stating: '...yet in one dream I can compose a whole Comedy, behold the

action, apprehend the jests and laugh my self-awake at the conceits

thereof'.

Samuel Pepys

in his diary entry for 15 August 1665 records a dream, stating: "I had

my Lady Castlemayne in my arms and was admitted to use all the dalliance

I desired with her, and then dreamt that this could not be awake, but

that it was only a dream".

19th century

In 1867, the French sinologist Marie-Jean-Léon, Marquis d'Hervey de Saint Denys anonymously published Les Rêves et Les Moyens de Les Diriger; Observations Pratiques

('Dreams and the ways to direct them; practical observations'), in

which he describes his own experiences of lucid dreaming, and proposes

that it is possible for anyone to learn to dream consciously.

20th century

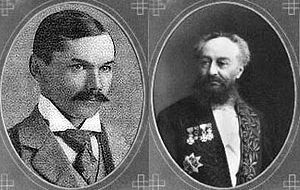

Frederik van Eeden and Marquis d'Hervey de Saint Denys, pioneers of lucid dreaming.

In 1913, Dutch psychiatrist and writer Frederik (Willem) van Eeden (1860–1932) coined the term 'lucid dream' in an article entitled "A Study of Dreams".

Some have suggested that the term is a misnomer because van Eeden

was referring to a phenomenon more specific than a lucid dream. Van Eeden intended the term lucid to denote "having insight", as in the phrase a lucid interval applied to someone in temporary remission from a psychosis, rather than as a reference to the perceptual quality of the experience, which may or may not be clear and vivid.

Scientific research

In 1968, Celia Green

analyzed the main characteristics of such dreams, reviewing previously

published literature on the subject and incorporating new data from

participants of her own. She concluded that lucid dreams were a category

of experience quite distinct from ordinary dreams and said they were

associated with rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep). Green was also the first to link lucid dreams to the phenomenon of false awakenings.

Lucid dreaming was subsequently researched by asking dreamers to

perform pre-determined physical responses while experiencing a dream,

including eye movement signals.

In 1980, Stephen LaBerge at Stanford University developed such techniques as part of his doctoral dissertation. In 1985, LaBerge performed a pilot study that showed that time perception

while counting during a lucid dream is about the same as during waking

life. Lucid dreamers counted out ten seconds while dreaming, signaling

the start and the end of the count with a pre-arranged eye signal

measured with electrooculogram recording. LaBerge's results were confirmed by German researchers D. Erlacher and M. Schredl in 2004.

In a further study by Stephen LaBerge, four subjects were

compared either singing while dreaming or counting while dreaming.

LaBerge found that the right hemisphere was more active during singing

and the left hemisphere was more active during counting.

Neuroscientist J. Allan Hobson

has hypothesized what might be occurring in the brain while lucid. The

first step to lucid dreaming is recognizing one is dreaming. This

recognition might occur in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is one of the few areas deactivated during REM sleep and where working memory

occurs. Once this area is activated and the recognition of dreaming

occurs, the dreamer must be cautious to let the dream continue but be

conscious enough to remember that it is a dream. While maintaining this

balance, the amygdala and parahippocampal cortex might be less intensely activated. To continue the intensity of the dream hallucinations, it is expected the pons and the parieto-occipital junction stay active.

Using electroencephalography

(EEG) and other polysomnographical measurements, LaBerge and others

have shown that lucid dreams begin in the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) stage

of sleep.

LaBerge also proposes that there are higher amounts of beta-1 frequency

band (13–19 Hz) brain wave activity experienced by lucid dreamers,

hence there is an increased amount of activity in the parietal lobes making lucid dreaming a conscious process.

Paul Tholey, a German Gestalt psychologist and a professor of psychology and sports science,

originally studied dreams in order to answer the question if one dreams

in colour or black and white. In his phenomenological research, he

outlined an epistemological frame using critical realism.

Tholey instructed his probands to continuously suspect waking life to

be a dream, in order that such a habit would manifest itself during

dreams. He called this technique for inducing lucid dreams the Reflexionstechnik reflection technique.

Probands learned to have such lucid dreams; they observed their dream

content and reported it soon after awakening. Tholey could examine the

cognitive abilities of dream figures.

Nine trained lucid dreamers were directed to set other dream figures

arithmetic and verbal tasks during lucid dreaming. Dream figures who

agreed to perform the tasks proved more successful in verbal than in

arithmetic tasks. Tholey discussed his scientific results with Stephen

LaBerge, who has a similar approach.

Alternative theories

Other researchers suggest that lucid dreaming is not a state of sleep, but of brief wakefulness, or "micro-awakening". Experiments by Stephen LaBerge used "perception of the outside world" as a criterion for wakefulness while studying lucid dreamers, and their sleep state was corroborated with physiological measurements.

LaBerge's subjects experienced their lucid dream while in a state of

REM, which critics felt may mean that the subjects are fully awake. J

Allen Hobson responded that lucid dreaming must be a state of both

waking and dreaming.

Philosopher Norman Malcolm

has argued against the possibility of checking the accuracy of dream

reports, pointing out that "the only criterion of the truth of a

statement that someone has had a certain dream is, essentially, his

saying so."

Definition

Paul Tholey laid the epistemological

basis for the research of lucid dreams, proposing seven different

conditions of clarity that a dream must fulfill in order to be defined

as a lucid dream:

- Awareness of the dream state (orientation)

- Awareness of the capacity to make decisions

- Awareness of memory functions

- Awareness of self

- Awareness of the dream environment

- Awareness of the meaning of the dream

- Awareness of concentration and focus (the subjective clarity of that state).

Later, in 1992, a study by Deirdre Barrett examined whether lucid dreams contained four "corollaries" of lucidity:

- The dreamer is aware that they are dreaming

- Objects disappear after waking

- Physical laws need not apply in the dream

- The dreamer has a clear memory of the waking world

Barrett found less than a quarter of lucidity accounts exhibited all four.

Subsequently, Stephen LaBerge

studied the prevalence of being able to control the dream scenario

among lucid dreams, and found that while dream control and dream

awareness are correlated, neither requires the other. LaBerge found

dreams that exhibit one clearly without the capacity for the other;

also, in some dreams where the dreamer is lucid and aware they could

exercise control, they choose simply to observe.

Prevalence and frequency

In 2016, a meta-analytic study by David Saunders and colleagues on 34 lucid dreaming studies, taken from a period of 50 years,

demonstrated that 55% of a pooled sample of 24,282 people claimed to

have experienced lucid dreams at least once or more in their lifetime.

Furthermore, for those that stated they did experience lucid dreams,

approximately 23% reported to experience them on a regular basis, as

often as once a month or more.

Suggested applications

Treating nightmares

It has been suggested that sufferers of nightmares

could benefit from the ability to be aware they are indeed dreaming. A

pilot study was performed in 2006 that showed that lucid dreaming

therapy treatment was successful in reducing nightmare frequency. This

treatment consisted of exposure to the idea, mastery of the technique,

and lucidity exercises. It was not clear what aspects of the treatment

were responsible for the success of overcoming nightmares, though the

treatment as a whole was said to be successful.

Australian psychologist Milan Colic has explored the application of principles from narrative therapy

to clients' lucid dreams, to reduce the impact not only of nightmares

during sleep but also depression, self-mutilation, and other problems in

waking life. Colic found that therapeutic conversations could reduce

the distressing content of dreams, while understandings about life—and

even characters—from lucid dreams could be applied to their lives with

marked therapeutic benefits.

Psychotherapists have applied lucid dreaming as a part of

therapy. Studies have shown that, by inducing a lucid dream, recurrent

nightmares can be alleviated. It is unclear whether this alleviation is

due to lucidity or the ability to alter the dream itself. A 2006 study

performed by Victor Spoormaker and Van den Bout evaluated the validity

of lucid dreaming treatment (LDT) in chronic nightmare sufferers.

LDT is composed of exposure, mastery and lucidity exercises. Results of

lucid dreaming treatment revealed that the nightmare frequency of the

treatment groups had decreased. In another study, Spoormaker, Van den

Bout, and Meijer (2003) investigated lucid dreaming treatment for

nightmares by testing eight subjects who received a one-hour individual

session, which consisted of lucid dreaming exercises. The results of the study revealed that the nightmare frequency had decreased and the sleep quality had slightly increased.

Holzinger, Klösch, and Saletu managed a psychotherapy study under

the working name of ‘Cognition during dreaming – a therapeutic

intervention in nightmares’, which included 40 subjects, men and women,

18–50 years old, whose life quality was significantly altered by

nightmares.

The test subjects were administered Gestalt group therapy and 24 of

them were also taught to enter the state of lucid dreaming by Holzinger.

This was purposefully taught in order to change the course of their

nightmares. The subjects then reported the diminishment of their

nightmare prevalence from 2–3 times a week to 2–3 times per month.

Creativity

In her book The Committee of Sleep, Deirdre Barrett

describes how some experienced lucid dreamers have learned to remember

specific practical goals such as artists looking for inspiration seeking

a show of their own work once they become lucid or computer programmers

looking for a screen with their desired code. However, most of these

dreamers had many experiences of failing to recall waking objectives

before gaining this level of control.

Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming by Stephen LaBerge and Howard Rheingold

(1990) discusses creativity within dreams and lucid dreams, including

testimonials from a number of people who claim they have used the

practice of lucid dreaming to help them solve a number of creative

issues, from an aspiring parent thinking of potential baby names to a

surgeon practicing surgical techniques. The authors discuss how

creativity in dreams could stem from "conscious access to the contents

of our unconscious minds"; access to "tacit knowledge" - the things we

know but can't explain, or things we know but are unaware that we know.

In popular culture

Risks

Though

lucid dreaming can be beneficial to a number of aspects of life, some

risks have been suggested. People who have never had the experience of

lucid dreaming may not understand what is happening when they first

experience a lucid dream. The person who lucid dreams could begin to

feel isolated from others due to feeling different. It could become more

difficult over time to wake up from a lucid dream. Someone struggling

with certain mental illnesses could find it hard to be able to tell the

difference between reality and the actual dream.

Long term risks with lucid dreaming have not been extensively studied.