The Internet protocol suite is the conceptual model and set of communications protocols used in the Internet and similar computer networks. It is commonly known as TCP/IP because the foundational protocols in the suite are the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP). During its development, versions of it were known as the Department of Defense (DoD) model because the development of the networking method was funded by the United States Department of Defense through DARPA. Its implementation is a protocol stack.

The Internet protocol suite provides end-to-end data communication specifying how data should be packetized, addressed, transmitted, routed, and received. This functionality is organized into four abstraction layers, which classify all related protocols according to the scope of networking involved. From lowest to highest, the layers are the link layer, containing communication methods for data that remains within a single network segment (link); the internet layer, providing internetworking between independent networks; the transport layer, handling host-to-host communication; and the application layer, providing process-to-process data exchange for applications.

The technical standards underlying the Internet protocol suite and its constituent protocols are maintained by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). The Internet protocol suite predates the OSI model, a more comprehensive reference framework for general networking systems.

History

Early research

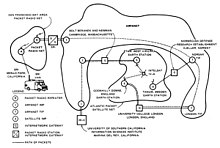

Diagram of the first internetworked connection

An SRI International Packet Radio Van, used for the first three-way internetworked transmission.

The Internet protocol suite resulted from research and development conducted by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the late 1960s. After initiating the pioneering ARPANET in 1969, DARPA started work on a number of other data transmission technologies. In 1972, Robert E. Kahn joined the DARPA Information Processing Technology Office,

where he worked on both satellite packet networks and ground-based

radio packet networks, and recognized the value of being able to

communicate across both. In the spring of 1973, Vinton Cerf, who helped develop the existing ARPANET Network Control Program (NCP) protocol, joined Kahn to work on open-architecture interconnection models with the goal of designing the next protocol generation for the ARPANET.

By the summer of 1973, Kahn and Cerf had worked out a fundamental

reformulation, in which the differences between local network protocols

were hidden by using a common internetwork protocol,

and, instead of the network being responsible for reliability, as in

the existing ARPANET protocols, this function was delegated to the

hosts. Cerf credits Hubert Zimmermann, Gérard Le Lann and Louis Pouzin, designer of the CYCLADES network, with important influences on this design. The new protocol was implemented as the Transmission Control Program in 1974.

Initially, the Transmission Control Program managed both datagram

transmissions and routing, but as experience with the protocol grew,

collaborators recommended division of functionality into layers of

distinct protocols. Advocates included Jonathan Postel of the University of Southern California's Information Sciences Institute, who edited the Request for Comments (RFCs), the technical and strategic document series that has both documented and catalyzed Internet development., and the research group of Robert Metcalfe at Xerox PARC. Postel stated, "We are screwing up in our design of Internet protocols by violating the principle of layering."

Encapsulation of different mechanisms was intended to create an

environment where the upper layers could access only what was needed

from the lower layers. A monolithic design would be inflexible and lead

to scalability issues. The Transmission Control Program was split into

two distinct protocols, the Internet Protocol as connectionless layer

and the Transmission Control Protocol as a reliable connection-oriented

service.

The design of the network included the recognition that it should

provide only the functions of efficiently transmitting and routing

traffic between end nodes and that all other intelligence should be

located at the edge of the network, in the end nodes. This design is

known as the end-to-end principle.

Using this design, it became possible to connect other networks to the

ARPANET that used the same principle, irrespective of other local

characteristics, thereby solving Kahn's initial internetworking problem.

A popular expression is that TCP/IP, the eventual product of Cerf and

Kahn's work, can run over "two tin cans and a string." Years later, as a joke, the IP over Avian Carriers formal protocol specification was created and successfully tested.

DARPA contracted with BBN Technologies, Stanford University, and the University College London

to develop operational versions of the protocol on several hardware

platforms. During development of the protocol the version number of the

packet routing layer progressed from version 1 to version 4, the latter

of which was installed in the ARPANET in 1983. It became known as Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) as the protocol that is still in use in the Internet, alongside its current successor, Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6).

Early Implementation

In

1975, a two-network TCP/IP communications test was performed between

Stanford and University College London. In November 1977, a

three-network TCP/IP test was conducted between sites in the US, the UK,

and Norway. Several other TCP/IP prototypes were developed at multiple

research centers between 1978 and 1983.

A computer called a router is provided with an interface to each network. It forwards network packets back and forth between them. Originally a router was called gateway, but the term was changed to avoid confusion with other types of gateways.

Adoption

In March 1982, the US Department of Defense declared TCP/IP as the standard for all military computer networking. In the same year, Peter T. Kirstein's research group at University College London adopted the protocol.

The migration of the ARPANET to TCP/IP was officially completed on flag day January 1, 1983, when the new protocols were permanently activated.

In 1985, the Internet Advisory Board (later Internet Architecture Board)

held a three-day TCP/IP workshop for the computer industry, attended by

250 vendor representatives, promoting the protocol and leading to its

increasing commercial use. In 1985, the first Interop

conference focused on network interoperability by broader adoption of

TCP/IP. The conference was founded by Dan Lynch, an early Internet

activist. From the beginning, large corporations, such as IBM and DEC,

attended the meeting.

IBM, AT&T and DEC were the first major corporations to adopt TCP/IP, this despite having competing proprietary protocols. In IBM, from 1984, Barry Appelman's

group did TCP/IP development. They navigated the corporate politics to

get a stream of TCP/IP products for various IBM systems, including MVS, VM, and OS/2. At the same time, several smaller companies, such as FTP Software and the Wollongong Group, began offering TCP/IP stacks for DOS and Microsoft Windows. The first VM/CMS TCP/IP stack came from the University of Wisconsin.

Some of the early TCP/IP stacks were written single-handedly by a few programmers. Jay Elinsky and Oleg Vishnepolsky of IBM Research wrote TCP/IP stacks for VM/CMS and OS/2, respectively. In 1984 Donald Gillies at MIT wrote a ntcp

multi-connection TCP which ran atop the IP/PacketDriver layer

maintained by John Romkey at MIT in 1983-4. Romkey leveraged this TCP

in 1986 when FTP Software was founded. Starting in 1985, Phil Karn created a multi-connection TCP application for ham radio systems (KA9Q TCP).

The spread of TCP/IP was fueled further in June 1989, when the University of California, Berkeley agreed to place the TCP/IP code developed for BSD UNIX

into the public domain. Various corporate vendors, including IBM,

included this code in commercial TCP/IP software releases. Microsoft

released a native TCP/IP stack in Windows 95. This event helped cement

TCP/IP's dominance over other protocols on Microsoft-based networks,

which included IBM Systems Network Architecture (SNA), and on other platforms such as Digital Equipment Corporation's DECnet, Open Systems Interconnection (OSI), and Xerox Network Systems (XNS).

The British academic network JANET converted to TCP/IP in 1991.

Formal specification and standards

The technical standards underlying the Internet protocol suite and its constituent protocols have been delegated to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).

The characteristic architecture of the Internet Protocol Suite is

its broad division into operating scopes for the protocols that

constitute its core functionality. The defining specification of the

suite is RFC 1122, which broadly outlines four abstraction layers.

These have stood the test of time, as the IETF has never modified this

structure. As such a model of networking, the Internet Protocol Suite

predates the OSI model, a more comprehensive reference framework for general networking systems.

Key architectural principles

Conceptual data flow in a simple network topology of two hosts (A and B)

connected by a link between their respective routers. The application

on each host executes read and write operations as if the processes were

directly connected to each other by some kind of data pipe. After

establishment of this pipe, most details of the communication are hidden

from each process, as the underlying principles of communication are

implemented in the lower protocol layers. In analogy, at the transport

layer the communication appears as host-to-host, without knowledge of

the application data structures and the connecting routers, while at the

internetworking layer, individual network boundaries are traversed at

each router.

Encapsulation of application data descending through the layers described in RFC 1122

The end-to-end principle

has evolved over time. Its original expression put the maintenance of

state and overall intelligence at the edges, and assumed the Internet

that connected the edges retained no state and concentrated on speed and

simplicity. Real-world needs for firewalls, network address

translators, web content caches and the like have forced changes in this

principle.

The robustness principle

states: "In general, an implementation must be conservative in its

sending behavior, and liberal in its receiving behavior. That is, it

must be careful to send well-formed datagrams, but must accept any

datagram that it can interpret (e.g., not object to technical errors

where the meaning is still clear)."

"The second part of the principle is almost as important: software on

other hosts may contain deficiencies that make it unwise to exploit

legal but obscure protocol features."

Encapsulation

is used to provide abstraction of protocols and services. Encapsulation

is usually aligned with the division of the protocol suite into layers

of general functionality. In general, an application (the highest level

of the model) uses a set of protocols to send its data down the layers.

The data is further encapsulated at each level.

An early architectural document, RFC 1122, emphasizes architectural principles over layering. RFC 1122, titled Host Requirements,

is structured in paragraphs referring to layers, but the document

refers to many other architectural principles and does not emphasize

layering. It loosely defines a four-layer model, with the layers having

names, not numbers, as follows:

- The application layer is the scope within which applications, or processes, create user data and communicate this data to other applications on another or the same host. The applications make use of the services provided by the underlying lower layers, especially the transport layer which provides reliable or unreliable pipes to other processes. The communications partners are characterized by the application architecture, such as the client-server model and peer-to-peer networking. This is the layer in which all application protocols, such as SMTP, FTP, SSH, HTTP, operate. Processes are addressed via ports which essentially represent services.

- The transport layer performs host-to-host communications on either the local network or remote networks separated by routers.[28] It provides a channel for the communication needs of applications. UDP is the basic transport layer protocol, providing an unreliable connectionless datagram service. The Transmission Control Protocol provides flow-control, connection establishment, and reliable transmission of data.

- The internet layer exchanges datagrams across network boundaries. It provides a uniform networking interface that hides the actual topology (layout) of the underlying network connections. It is therefore also the layer that establishes internetworking. Indeed, it defines and establishes the Internet. This layer defines the addressing and routing structures used for the TCP/IP protocol suite. The primary protocol in this scope is the Internet Protocol, which defines IP addresses. Its function in routing is to transport datagrams to the next host, functioning as an IP router, that has the connectivity to a network closer to the final data destination.

- The link layer defines the networking methods within the scope of the local network link on which hosts communicate without intervening routers. This layer includes the protocols used to describe the local network topology and the interfaces needed to affect transmission of Internet layer datagrams to next-neighbor hosts.

Link layer

The protocols of the link layer operate within the scope of the local network connection to which a host is attached. This regime is called the link

in TCP/IP parlance and is the lowest component layer of the suite. The

link includes all hosts accessible without traversing a router. The size

of the link is therefore determined by the networking hardware design.

In principle, TCP/IP is designed to be hardware independent and may be

implemented on top of virtually any link-layer technology. This includes

not only hardware implementations, but also virtual link layers such as

virtual private networks and networking tunnels.

The link layer is used to move packets between the Internet layer

interfaces of two different hosts on the same link. The processes of

transmitting and receiving packets on the link can be controlled both in

the software device driver for the network card, as well as in firmware or by specialized chipsets.

These perform functions, such as framing, to prepare the Internet layer

packets for transmission, and finally transmit the frames over a physical medium.

The TCP/IP model includes specifications of translating the network

addressing methods used in the Internet Protocol to link layer

addresses, such as media access control

(MAC) addresses. All other aspects below that level, however, are

implicitly assumed to exist, and are not explicitly defined in the

TCP/IP model.

The link layer in the TCP/IP model has corresponding functions in Layer 2 of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model.

Internet layer

The internet layer has the responsibility of sending packets across potentially multiple networks. Internetworking requires sending data from the source network to the destination network. This process is called routing.

The Internet Protocol performs two basic functions:

- Host addressing and identification: This is accomplished with a hierarchical IP addressing system.

- Packet routing: This is the basic task of sending packets of data (datagrams) from source to destination by forwarding them to the next network router closer to the final destination.

The internet layer is not only agnostic of data structures at the

transport layer, but it also does not distinguish between operation of

the various transport layer protocols. IP carries data for a variety of

different upper layer protocols. These protocols are each identified by a unique protocol number: for example, Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) and Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP) are protocols 1 and 2, respectively.

Some of the protocols carried by IP, such as ICMP which is used

to transmit diagnostic information, and IGMP which is used to manage IP Multicast

data, are layered on top of IP but perform internetworking functions.

This illustrates the differences in the architecture of the TCP/IP stack

of the Internet and the OSI model. The TCP/IP model's internet layer

corresponds to layer three of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI)

model, where it is referred to as the network layer.

The internet layer provides an unreliable datagram transmission

facility between hosts located on potentially different IP networks by

forwarding the transport layer datagrams to an appropriate next-hop

router for further relaying to its destination. With this functionality,

the internet layer makes possible internetworking, the interworking of

different IP networks, and it essentially establishes the Internet. The

Internet Protocol is the principal component of the internet layer, and

it defines two addressing systems to identify network hosts' computers,

and to locate them on the network. The original address system of the ARPANET and its successor, the Internet, is Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4). It uses a 32-bit IP address

and is therefore capable of identifying approximately four billion

hosts. This limitation was eliminated in 1998 by the standardization of Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) which uses 128-bit addresses. IPv6 production implementations emerged in approximately 2006.

Transport layer

The

transport layer establishes basic data channels that applications use

for task-specific data exchange. The layer establishes host-to-host

connectivity, meaning it provides end-to-end message transfer services

that are independent of the structure of user data and the logistics of

exchanging information for any particular specific purpose and

independent of the underlying network. The protocols in this layer may

provide error control, segmentation, flow control, congestion control, and application addressing (port numbers). End-to-end message transmission or connecting applications at the transport layer can be categorized as either connection-oriented, implemented in TCP, or connectionless, implemented in UDP.

For the purpose of providing process-specific transmission channels for applications, the layer establishes the concept of the network port.

This is a numbered logical construct allocated specifically for each of

the communication channels an application needs. For many types of

services, these port numbers

have been standardized so that client computers may address specific

services of a server computer without the involvement of service

announcements or directory services.

Because IP provides only a best effort delivery, some transport layer protocols offer reliability. However, IP can run over a reliable data link protocol such as the High-Level Data Link Control (HDLC).

For example, the TCP is a connection-oriented protocol that addresses numerous reliability issues in providing a reliable byte stream:

- data arrives in-order

- data has minimal error (i.e., correctness)

- duplicate data is discarded

- lost or discarded packets are resent

- includes traffic congestion control

The newer Stream Control Transmission Protocol

(SCTP) is also a reliable, connection-oriented transport mechanism. It

is message-stream-oriented—not byte-stream-oriented like TCP—and

provides multiple streams multiplexed over a single connection. It also

provides multi-homing

support, in which a connection end can be represented by multiple IP

addresses (representing multiple physical interfaces), such that if one

fails, the connection is not interrupted. It was developed initially for

telephony applications (to transport SS7 over IP), but can also be used for other applications.

The User Datagram Protocol is a connectionless datagram protocol. Like IP, it is a best effort, "unreliable" protocol. Reliability is addressed through error detection using a weak checksum algorithm. UDP is typically used for applications such as streaming media (audio, video, Voice over IP etc.) where on-time arrival is more important than reliability, or for simple query/response applications like DNS lookups, where the overhead of setting up a reliable connection is disproportionately large. Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) is a datagram protocol that is designed for real-time data such as streaming audio and video.

The applications at any given network address are distinguished by their TCP or UDP port. By convention certain well known ports are associated with specific applications.

The TCP/IP model's transport or host-to-host layer corresponds

roughly to the fourth layer in the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI)

model, also called the transport layer.

Application layer

The application layer

includes the protocols used by most applications for providing user

services or exchanging application data over the network connections

established by the lower level protocols. This may include some basic

network support services such as protocols for routing and host

configuration. Examples of application layer protocols include the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), and the Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). Data coded according to application layer protocols are encapsulated into transport layer protocol units (such as TCP or UDP messages), which in turn use lower layer protocols to effect actual data transfer.

The TCP/IP model does not consider the specifics of formatting

and presenting data, and does not define additional layers between the

application and transport layers as in the OSI model (presentation and

session layers). Such functions are the realm of libraries and application programming interfaces.

Application layer protocols generally treat the transport layer (and lower) protocols as black boxes

which provide a stable network connection across which to communicate,

although the applications are usually aware of key qualities of the

transport layer connection such as the end point IP addresses and port

numbers. Application layer protocols are often associated with

particular client-server applications, and common services have well-known port numbers reserved by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). For example, the HyperText Transfer Protocol uses server port 80 and Telnet uses server port 23. Clients connecting to a service usually use ephemeral ports,

i.e., port numbers assigned only for the duration of the transaction at

random or from a specific range configured in the application.

The transport layer and lower-level layers are unconcerned with the specifics of application layer protocols. Routers and switches do not typically examine the encapsulated traffic, rather they just provide a conduit for it. However, some firewall and bandwidth throttling applications must interpret application data. An example is the Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP). It is also sometimes necessary for network address translator (NAT) traversal to consider the application payload.

The application layer in the TCP/IP model is often compared as

equivalent to a combination of the fifth (Session), sixth

(Presentation), and the seventh (Application) layers of the Open Systems

Interconnection (OSI) model.

Furthermore, the TCP/IP model distinguishes between user protocols and support protocols.

Support protocols provide services to a system of network

infrastructure. User protocols are used for actual user applications.

For example, FTP is a user protocol and DNS is a support protocol.

Comparison of TCP/IP and OSI layering

The

three top layers in the OSI model, i.e. the application layer, the

presentation layer and the session layer, are not distinguished

separately in the TCP/IP model which only has an application layer above

the transport layer. While some pure OSI protocol applications, such as

X.400,

also combined them, there is no requirement that a TCP/IP protocol stack

must impose monolithic architecture above the transport layer. For

example, the NFS application protocol runs over the eXternal Data Representation (XDR) presentation protocol, which, in turn, runs over a protocol called Remote Procedure Call (RPC). RPC provides reliable record transmission, so it can safely use the best-effort UDP transport.

Different authors have interpreted the TCP/IP model differently,

and disagree whether the link layer, or the entire TCP/IP model, covers

OSI layer 1 (physical layer) issues, or whether a hardware layer is assumed below the link layer.

Several authors have attempted to incorporate the OSI model's

layers 1 and 2 into the TCP/IP model, since these are commonly referred

to in modern standards (for example, by IEEE and ITU).

This often results in a model with five layers, where the link layer or

network access layer is split into the OSI model's layers 1 and 2.

The IETF protocol development effort is not concerned with strict

layering. Some of its protocols may not fit cleanly into the OSI model,

although RFCs sometimes refer to it and often use the old OSI layer

numbers. The IETF has repeatedly stated that Internet protocol and architecture development is not intended to be OSI-compliant. RFC 3439, addressing Internet architecture, contains a section entitled: "Layering Considered Harmful".

For example, the session and presentation layers of the OSI suite

are considered to be included to the application layer of the TCP/IP

suite. The functionality of the session layer can be found in protocols

like HTTP and SMTP and is more evident in protocols like Telnet and the Session Initiation Protocol

(SIP). Session layer functionality is also realized with the port

numbering of the TCP and UDP protocols, which cover the transport layer

in the TCP/IP suite. Functions of the presentation layer are realized in

the TCP/IP applications with the MIME standard in data exchange.

Conflicts are apparent also in the original OSI model, ISO 7498,

when not considering the annexes to this model, e.g., the ISO 7498/4

Management Framework, or the ISO 8648 Internal Organization of the

Network layer (IONL). When the IONL and Management Framework documents

are considered, the ICMP and IGMP are defined as layer management

protocols for the network layer. In like manner, the IONL provides a

structure for "subnetwork dependent convergence facilities" such as ARP and RARP.

IETF protocols can be encapsulated recursively, as demonstrated by tunneling protocols such as Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE). GRE uses the same mechanism that OSI uses for tunneling at the network layer.

Implementations

The Internet protocol suite does not presume any specific hardware or

software environment. It only requires that hardware and a software

layer exists that is capable of sending and receiving packets on a

computer network. As a result, the suite has been implemented on

essentially every computing platform. A minimal implementation of TCP/IP

includes the following: Internet Protocol (IP), Address Resolution Protocol (ARP), Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), User Datagram Protocol (UDP), and Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP). In addition to IP, ICMP, TCP, UDP, Internet Protocol version 6 requires Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP), ICMPv6, and IGMPv6 and is often accompanied by an integrated IPSec security layer.

Application programmers are typically concerned only with

interfaces in the application layer and often also in the transport

layer, while the layers below are services provided by the TCP/IP stack

in the operating system. Most IP implementations are accessible to

programmers through sockets and APIs.

Unique implementations include Lightweight TCP/IP, an open source stack designed for embedded systems, and KA9Q NOS, a stack and associated protocols for amateur packet radio systems and personal computers connected via serial lines.

Microcontroller firmware in the network adapter typically handles

link issues, supported by driver software in the operating system.

Non-programmable analog and digital electronics are normally in charge

of the physical components below the link layer, typically using an application-specific integrated circuit

(ASIC) chipset for each network interface or other physical standard.

High-performance routers are to a large extent based on fast

non-programmable digital electronics, carrying out link level switching.