While many assume urban design is about the process of designing and shaping the physical features of cities, and regional spaces, it is also about social design and other larger scale issues. Linking the fields of architecture as well as planning to better organize physical space and community environments.

Some important focuses of urban design on this page include its historical impact, paradigm shifts, its interdisciplinary nature, and issues related to urban design.

Theory

Urban design deals with the larger scale of groups of buildings, infrastructure, streets, and public spaces, entire neighbourhoods and districts, and entire cities, with the goal of making urban environments that are equitable, beautiful, performative, and sustainable.

Urban design is an interdisciplinary field that utilizes the procedures and the elements of architecture and other related professions, including landscape design, urban planning, civil engineering, and municipal engineering. It borrows substantive and procedural knowledge from public administration, sociology, law, urban geography, urban economics and other related disciplines from the social and behavioral sciences, as well as from the natural sciences. In more recent times different sub-subfields of urban design have emerged such as strategic urban design, landscape urbanism, water-sensitive urban design, and sustainable urbanism. Urban design demands an understanding of a wide range of subjects from physical geography to social science, and an appreciation for disciplines, such as real estate development, urban economics, political economy, and social theory.

Urban designers work to create inclusive cities that protect the commons, ensure equal access to and distribution of public goods, and meet the needs of all residents, particularly women, people of color, and other marginalized populations. Through design interventions, urban designers work to revolutionize the way we conceptualize our social, political, and spatial systems as strategies to produce and reproduce a more equitable and innovative future.

Urban design is about making connections between people and places, movement and urban form, nature and the built fabric. Urban design draws together the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity, and economic viability into the creation of places with distinct beauty and identity. Urban design draws these and other strands together, creating a vision for an area and then deploying the resources and skills needed to bring the vision to life.

Urban design theory deals primarily with the design and management of public space (i.e. the 'public environment', 'public realm' or 'public domain'), and the way public places are used and experienced. Public space includes the totality of spaces used freely on a day-to-day basis by the general public, such as streets, plazas, parks, and public infrastructure. Some aspects of privately owned spaces, such as building facades or domestic gardens, also contribute to public space and are therefore also considered by urban design theory. Important writers on urban design theory include Christopher Alexander, Peter Calthorpe, Gordon Cullen, Andres Duany, Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl, Allan B. Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, Aldo Rossi, Colin Rowe, Robert Venturi, William H. Whyte, Camillo Sitte, Bill Hillier (Space syntax), and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk.

History

Although contemporary professional use of the term 'urban design' dates from the mid-20th century, urban design as such has been practiced throughout history. Ancient examples of carefully planned and designed cities exist in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas, and are particularly well known within Classical Chinese, Roman, and Greek cultures. Specifically, Hippodamus of Miletus was a famous ancient Greek architect and urban planner, and all around academic that is often considered to be a "father of European urban planning", and the namesake of the "Hippodamian plan", also known as the grid plan of a city layout.

European Medieval cities are often, and often erroneously, regarded as exemplars of undesigned or 'organic' city development. There are many examples of considered urban design in the Middle Ages. In England, many of the towns listed in the 9th-century Burghal Hidage were designed on a grid, examples including Southampton, Wareham, Dorset and Wallingford, Oxfordshire, having been rapidly created to provide a defensive network against Danish invaders. 12th century western Europe brought renewed focus on urbanisation as a means of stimulating economic growth and generating revenue. The burgage system dating from that time and its associated burgage plots brought a form of self-organising design to medieval towns. Rectangular grids were used in the Bastides of 13th and 14th century Gascony, and the new towns of England created in the same period.

Throughout history, the design of streets and deliberate configuration of public spaces with buildings have reflected contemporaneous social norms or philosophical and religious beliefs. Yet the link between designed urban space and the human mind appears to be bidirectional. Indeed, the reverse impact of urban structure upon human behaviour and upon thought is evidenced by both observational study and historical records. There are clear indications of impact through Renaissance urban design on the thought of Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei. Already René Descartes in his Discourse on the Method had attested to the impact Renaissance planned new towns had upon his own thought, and much evidence exists that the Renaissance streetscape was also the perceptual stimulus that had led to the development of coordinate geometry.

Early modern era

- Early modern

Vienna Ring Road, Vienna, (Georges-Eugène Haussmann)

Circus, Bath completed in 1768

The beginnings of modern urban design in Europe are associated with the Renaissance but, especially, with the Age of Enlightenment. Spanish colonial cities were often planned, as were some towns settled by other imperial cultures. These sometimes embodied utopian ambitions as well as aims for functionality and good governance, as with James Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah, Georgia. In the Baroque period the design approaches developed in French formal gardens such as Versailles were extended into urban development and redevelopment. In this period, when modern professional specializations did not exist, urban design was undertaken by people with skills in areas as diverse as sculpture, architecture, garden design, surveying, astronomy, and military engineering. In the 18th and 19th centuries, urban design was perhaps most closely linked with surveyors engineers and architects. The increase in urban populations brought with it problems of epidemic disease, the response to which was a focus on public health, the rise in the UK of municipal engineering and the inclusion in British legislation of provisions such as minimum widths of street in relation to heights of buildings in order to ensure adequate light and ventilation.

Much of Frederick Law Olmsted's work was concerned with urban design, and the newly formed profession of landscape architecture also began to play a significant role in the late 19th century.

Modern urban design

In the 19th century, cities were industrializing and expanding at a tremendous rate. Private businesses largely dictated the pace and style of this development. The expansion created many hardships for the working poor and concern for public health increased. However, the laissez-faire style of government, in fashion for most of the Victorian era, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism. This gave more power to the public. The public wanted the government to provide citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. Around 1900, modern urban design emerged from developing theories on how to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age.

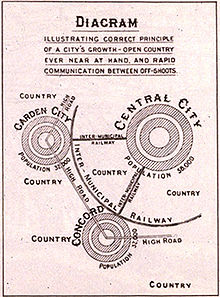

The first modern urban planning theorist was Sir Ebenezer Howard. His ideas, although utopian, were adopted around the world because they were highly practical. He initiated the garden city movement in 1898 garden city movement. His garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by parks. Howard wanted the cities to be proportional with separate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. Inspired by the Utopian novel Looking Backward and Henry George's work Progress and Poverty, Howard published his book Garden Cities of To-morrow in 1898. His work is an important reference in the history of urban planning. He envisioned the self-sufficient garden city to house 32,000 people on a site of 6,000 acres (2,428 ha). He planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks, and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the center. When it reached full population, Howard wanted another garden city to be developed nearby. He envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail. His model for a garden city was first created at Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire. Howard's movement was extended by Sir Frederic Osborn to regional planning.

20th century

In the early 1900s, urban planning became professionalized. With input from utopian visionaries, civil engineers, and local councilors, new approaches to city design were developed for consideration by decision-makers such as elected officials. In 1899, the Town and Country Planning Association was founded. In 1909, the first academic course on urban planning was offered by the University of Liverpool. Urban planning was first officially embodied in the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909 Howard's 'garden city' compelled local authorities to introduce a system where all housing construction conformed to specific building standards. In the United Kingdom following this Act, surveyor, civil engineers, architects, and lawyers began working together within local authorities. In 1910, Thomas Adams became the first Town Planning Inspector at the Local Government Board and began meeting with practitioners. In 1914, The Town Planning Institute was established. The first urban planning course in America wasn't established until 1924 at Harvard University. Professionals developed schemes for the development of land, transforming town planning into a new area of expertise.

In the 20th century, urban planning was changed by the automobile industry. Car-oriented design impacted the rise of 'urban design'. City layouts now revolved around roadways and traffic patterns.

In June 1928, the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) was founded at the Chateau de la Sarraz in Switzerland, by a group of 28 European architects organized by Le Corbusier, Hélène de Mandrot, and Sigfried Giedion. The CIAM was one of many 20th century manifestos meant to advance the cause of "architecture as a social art".

- Modernism

Palace of Assembly (Chandigarh) (1952–1961) (Le Corbusier)

FDR Drive designed by Robert Moses

Postwar

Team X was a group of architects and other invited participants who assembled starting in July 1953 at the 9th Congress of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) and created a schism within CIAM by challenging its doctrinaire approach to urbanism.

In 1956, the term "Urban design" was first used at a series of conferences hosted by Harvard University. The event provided a platform for Harvard's Urban Design program. The program also utilized the writings of famous urban planning thinkers: Gordon Cullen, Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, and Christopher Alexander.

In 1961, Gordon Cullen published The Concise Townscape. He examined the traditional artistic approach to city design of theorists including Camillo Sitte, Barry Parker, and Raymond Unwin. Cullen also created the concept of 'serial vision'. It defined the urban landscape as a series of related spaces.

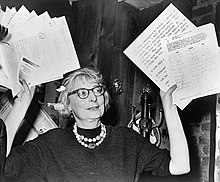

Also in 1961, Jane Jacobs published The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She critiqued the modernism of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture). Jacobs also claimed crime rates in publicly owned spaces were rising because of the Modernist approach of 'city in the park'. She argued instead for an 'eyes on the street' approach to town planning through the resurrection of main public space precedents (e.g. streets, squares).

In the same year, Kevin Lynch published The Image of the City. He was seminal to urban design, particularly with regards to the concept of legibility. He reduced urban design theory to five basic elements: paths, districts, edges, nodes, landmarks. He also made the use of mental maps to understand the city popular, rather than the two-dimensional physical master plans of the previous 50 years.

Other notable works:

- Architecture of the City by Aldo Rossi (1966)

- Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (1972)

- Collage City by Colin Rowe (1978)

- The Next American Metropolis by Peter Calthorpe (1993)

- The Social Logic of Space by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson (1984)

The popularity of these works resulted in terms that become everyday language in the field of urban planning. Aldo Rossi introduced 'historicism' and 'collective memory' to urban design. Rossi also proposed a 'collage metaphor' to understand the collection of new and old forms within the same urban space. Peter Calthorpe developed a manifesto for sustainable urban living via medium-density living. He also designed a manual for building new settlements in his concept of Transit Oriented Development (TOD). Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson introduced Space Syntax to predict how movement patterns in cities would contribute to urban vitality, anti-social behaviour, and economic success. 'Sustainability', 'livability', and 'high quality of urban components' also became commonplace in the field.

Current trends

- New Urbanism

Market Street, Celebration, Florida

Poundbury, Dorset

Today, urban design seeks to create sustainable urban environments with long-lasting structures, buildings, and overall livability. Walkable urbanism is another approach to practice that is defined within the Charter of New Urbanism. It aims to reduce environmental impacts by altering the built environment to create smart cities that support sustainable transport. Compact urban neighborhoods encourage residents to drive less. These neighborhoods have significantly lower environmental impacts when compared to sprawling suburbs. To prevent urban sprawl, Circular flow land use management was introduced in Europe to promote sustainable land use patterns.

As a result of the recent New Classical Architecture movement, sustainable construction aims to develop smart growth, walkability, architectural tradition, and classical design. It contrasts with modernist and globally uniform architecture. In the 1980s, urban design began to oppose the increasing solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl. Managed Urbanisation with the view to making the urbanising process completely culturally and economically, and environmentally sustainable, and as a possible solution to the urban sprawl, Frank Reale has submitted an interesting concept of Expanding Nodular Development (E.N.D.) that integrates many urban designs and ecological principles, to design and build smaller rural hubs with high-grade connecting freeways, rather than adding more expensive infrastructure to existing big cities and the resulting congestion.

Paradigm shifts

Throughout the young existence of the Urban Design discipline, many paradigm shifts have occurred that have affected the trajectory of the field regarding theory and practice. These paradigm shifts cover multiple subject areas outside of the traditional design disciplines.

- Team 10 - The first major paradigm shift was the formation of Team 10 out of CIAM, or the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne. They believed that Urban Design should introduce ideas of ‘Human Association’, which pivots the design focus from the individual patron to concentrating on the collective urban population.

- The Brundtland Report and Silent Spring - Another paradigm shift was the publication of the Brundtland Report and the book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. These writings introduced the idea that human settlements could have detrimental impacts on ecological processes, as well as human health, which spurred a new era of environmental awareness in the field.

- The Planner's Triangle - The Planner's Triangle, created by Scott Cambell, emphasized three main conflicts in the planning process. This diagram exposed the complex relationships between Economic Development, Environmental Protection, and Equity and Social Justice. For the first time, the concept of Equity and Social Justice was considered as equally important as Economic Development and Environmental Protection within the design process.

- Death of Modernism (Demolition of Pruitt Igoe) - Pruitt Igoe was a spatial symbol and representation of Modernist theory regarding social housing. In its failure and demolition, these theories were put into question and many within the design field considered the era of Modernism to be dead.

- Neoliberalism & the election of Reagan - The election of President Reagan and the rise of Neoliberalism affected the Urban Design discipline because it shifted the planning process to emphasize capitalistic gains and spatial privatization. Inspired by the trickle-down approach of Reaganomics, it was believed that the benefits of a capitalist emphasis within design would positively impact everyone. Conversely, this led to exclusionary design practices and to what many consider as “the death of public space”.

- Right to the City - The spatial and political battle over our citizens' rights to the city has been an ongoing one. David Harvey, along with Dan Mitchell and Edward Soja, discussed rights to the city as a matter of shifting the historical thinking of how spatial matter was determined in a critical form. This change of thinking occurred in three forms: ontologically, sociologically, and the combination of this socio-spatial dialect. Together the aim shifted to be able to measure what matters in a socio-spatial context.

- Black Lives Matter (Ferguson) - The Black Lives Matter movement challenged design thinking because it emphasized the injustices and inequities suffered by people of color in urban space, as well as emphasized their right to public space without discrimination and brutality. It claims that minority groups lack certain spatial privileges and that this deficiency can result in matters of life and death. In order to reach an equitable state of urbanism, there needs to be equal identification of socio-economic lives within our urbanscapes.

New approaches

There have been many different theories and approaches applied to the practice of urban design.

New Urbanism is an approach that began in the 1980s as a place-making initiative to combat suburban sprawl. Its goal is to increase density by creating compact and complete towns and neighborhoods. The 10 principles of new urbanism are walkability, connectivity, mixed-use and diversity, mixed housing, quality architecture and urban design, traditional neighborhood structure, increased density, smart transportation, sustainability, and quality of life. New urbanism and the developments that it has created are sources of debates within the discipline, primarily with the landscape urbanist approach but also due to its reproduction of idyllic architectural tropes that do not respond to the context. Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Peter Calthorpe, and Jeff Speck are all strongly associated with New Urbanism and its evolution over the years.

Landscape Urbanism is a theory that first surfaced in the 1990s, arguing that the city is constructed of interconnected and ecologically rich horizontal field conditions, rather than the arrangement of objects and buildings. Charles Waldheim, Mohsen Mostafavi, James Corner, and Richard Weller are closely associated with this theory. Landscape urbanism theorises sites, territories, ecosystems, networks, and infrastructures through landscape practice according to Corner, while applying a dynamic concept to cities as ecosystems that grow, shrink or change phases of development according to Waldheim.

Everyday Urbanism is a concept introduced by Margaret Crawford and influenced by Henry Lefebvre that describes the everyday lived experience shared by urban residents including commuting, working, relaxing, moving through city streets and sidewalks, shopping, buying, eating food, and running errands. Everyday urbanism is not concerned with aesthetic value. Instead, it introduces the idea of eliminating the distance between experts and ordinary users and forces designers and planners to contemplate a 'shift of power' and address social life from a direct and ordinary perspective.

Tactical Urbanism (also known as DIY Urbanism, Planning-by-Doing, Urban Acupuncture, or Urban Prototyping) is a city, organizational, or citizen-led approach to neighborhood-building that uses short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies to catalyze long term change.

Top-up Urbanism is the theory and implementation of two techniques in urban design: top-down and bottom-up. Top-down urbanism is when the design is implemented from the top of the hierarchy - normally the government or planning department. Bottom-up or grassroots urbanism begins with the people or the bottom of the hierarchy. Top-up means that both methods are used together to make a more participatory design, so it is sure to be comprehensive and well regarded in order to be as successful as possible.

Infrastructural Urbanism is the study of how the major investments that go into making infrastructural systems can be leveraged to be more sustainable for communities. Instead of the systems being solely about efficiency in both cost and production, infrastructural urbanism strives to utilize these investments to be more equitable for social and environmental issues as well. Linda Samuels is a designer investigating how to accomplish this change in infrastructure in what she calls "next-generation infrastructure" which is “multifunctional; public; visible; socially productive; locally specific, flexible, and adaptable; sensitive to the eco-economy; composed of design prototypes or demonstration projects; symbiotic; technologically smart; and developed collaboratively across disciplines and agencies.”

Sustainable Urbanism is the study from the 1990s of how a community can be beneficial for the ecosystem, the people, and the economy for which it is associated. It is based on Scott Campbell's planner's triangle which tries to find the balance between economy, equity, and the environment. Its main concept is to try and make cities as self-sufficient as possible while not damaging the ecosystem around them, today with an increased focus on climate stability. A key designer working with sustainable urbanism is Douglas Farr.

Feminist Urbanism is the study and critique of how the built environment affects genders differently because of patriarchal social and political structures in society. Typically, the people at the table making design decisions are men, so their conception about public space and the built environment relates to their life perspectives and experiences, which do not reflect the same experiences of women or children. Dolores Hayden is a scholar who has researched this topic from 1980 to the present day. Hayden's writing says, “when women, men, and children of all classes and races can identify the public domain as the place where they feel most comfortable as citizens, Americans will finally have homelike urban space.”

Educational Urbanism is an emerging discipline, at the crossroads of urban planning, educational planning, and pedagogy. An approach that tackles the notion that economic activities, the need for new skills at the workplace, and the spatial configuration of the workplace rely on the spatial reorientation in the design of educational spaces and the urban dimension of educational planning.

Black Urbanism is an approach in which black communities are active creators, innovators, and authors of the process of designing and creating the neighborhoods and spaces of the metropolitan areas they have done so much to help revive over the past half-century. The goal is not to build black cities for black people but to explore and develop the creative energy that exists in so-called black areas: that has the potential to contribute to the sustainable development of the whole city.

Debates in urbanism

Underlying the practice of urban design are the many theories about how to best design the city. Each theory makes a unique claim about how to effectively design thriving, sustainable urban environments. Debates over the efficacy of these approaches fill the urban design discourse. Landscape Urbanism and New Urbanism are commonly debated as distinct approaches to addressing suburban sprawl. While Landscape Urbanism proposes landscape as the basic building block of the city and embraces horizontality, flexibility, and adaptability, New Urbanism offers the neighborhood as the basic building block of the city and argues for increased density, mixed uses, and walkability. Opponents of Landscape Urbanism point out that most of its projects are urban parks, and as such, its application is limited. Opponents of New Urbanism claim that its preoccupation with traditional neighborhood structures is nostalgic, unimaginative, and culturally problematic. Everyday Urbanism argues for grassroots neighborhood improvements rather than master-planned, top-down interventions. Each theory elevates the roles of certain professions in the urban design process, further fueling the debate. In practice, urban designers often apply principles from many urban design theories. Emerging from the conversation is a universal acknowledgement of the importance of increased interdisciplinary collaboration in designing the modern city.

Urban design as an integrative profession

Urban designers work with architects, landscape architects, transportation engineers, urban planners, and industrial designers to reshape the city. Cooperation with public agencies, authorities and the interests of nearby property owners is necessary to manage public spaces. Users often compete over the spaces and negotiate across a variety of spheres. Input is frequently needed from a wide range of stakeholders. This can lead to different levels of participation as defined in Arnstein's Ladder of Citizen Participation.

While there are some professionals who identify themselves specifically as urban designers, a majority have backgrounds in urban planning, architecture, or landscape architecture. Many collegiate programs incorporate urban design theory and design subjects into their curricula. There is an increasing number of university programs offering degrees in urban design at the post-graduate level.

Urban design considers:

- Pedestrian zones

- Incorporation of nature within a city

- Aesthetics

- Urban structure – arrangement and relation of business and people

- Urban typology, density, and sustainability - spatial types and morphologies related to the intensity of use, consumption of resources, production, and maintenance of viable communities

- Accessibility – safe and easy transportation

- Legibility and wayfinding – accessible information about travel and destinations

- Animation – Designing places to stimulate public activity

- Function and fit – places support their varied intended uses

- Complimentary mixed uses – Locating activities to allow constructive interaction between them

- Character and meaning – Recognizing differences between places

- Order and incident – Balancing consistency and variety in the urban environment

- Continuity and change – Locating people in time and place, respecting heritage and contemporary culture

- Civil society – people are free to interact as civic equals, important for building social capital

- Participation/engagement – including people in the decision-making process can be done at many different scales.

The original urban design was thought to be separated from architecture and urban planning. Urban Design has developed to a certain extent, and comes from the foundation of engineering. In Anglo-Saxon countries, it is often considered as a branch under the architecture, urban planning, and landscape architecture and limited as the construction of the urban physical environment. However Urban Design is more integrated into the social science-based, cultural, economic, political, and other aspects. Not only focus on space and architectural group, but also look at the whole city from a broader and more holistic perspective to shape a better living environment. Compared to architecture, the spatial and temporal scale of Urban Design processing is much larger. It deals with neighborhoods, communities, and even the entire city.

The urban design education

Following the 1956 Urban Design conference, Harvard University established the first graduate program with urban design in its title, The Master of Architecture in Urban Design, although as a subject taught in universities its history in Europe is far older. Urban design programs explore the built environment from diverse disciplinary backgrounds and points of view. The pedagogically innovative combination of interdisciplinary studios, lecture courses, seminars, and independent study creates an intimate and engaging educational atmosphere in which students thrive and learn. Soon after in 1961, Washington University in St. Louis founded their Master of Urban Design program. Today, twenty urban design programs exist in the United States:

- Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI

- Ball State University - Indianapolis, IN

- Clemson University - Charleston, SC

- Columbia University - New York, NY

- City College of New York - New York, NY

- Georgia Tech - Atlanta, GA

- Harvard University - Cambridge, MA

- Iowa State University - Ames, IA

- New York Institute of Technology - New York, NY

- Pratt - Brooklyn, NY

- Savannah College of Art and Design - Savannah, GA

- University of California - Berkeley, CA

- University of Colorado Denver - Denver, CO

- University of Maryland - College Park, MD

- University of Miami - Miami, FL

- University of Michigan - Ann Arbor, MI

- University of Notre Dame - Notre Dame, IN

- University of Pennsylvania - Philadelphia, PA

- University of Texas - Austin, TX

- Washington University in St. Louis - St. Louis, MO

- University of North Carolina at Charlotte - Charlotte, NC

Issues

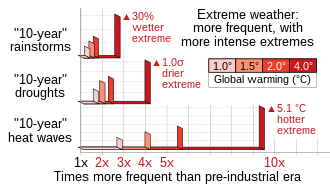

The field of urban design holds enormous potential for helping us address today's biggest challenges: an expanding population, mass urbanization, rising inequality, and climate change. In its practice as well as its theories, urban design attempts to tackle these pressing issues. As climate change progresses, urban design can mitigate the results of flooding, temperature changes, and increasingly detrimental storm impacts through a mindset of sustainability and resilience. In doing so, the urban design discipline attempts to create environments that are constructed with longevity in mind. Cities today must be designed to minimize resource consumption, waste generation, and pollution while also withstanding the unknown impacts of climate change. To be truly resilient, our cities need to be able to not just bounce back from a catastrophic climate event but to bounce forward to an improved state.

Another issue in this field is that it is often assumed that there are no mothers of planning and urban design. However, this is not the case, many women have made proactive contributions to the field, including the work of Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, Florence Kelley, and Lillian Wald, to name a few of whom were prominent leaders in the City Social movement. The City Social was a movement that steamed between the commonly known City Practical and City Beautiful movements. It was a movement that’s main concerns lay with the economic and social equalities regarding urban issues.

Justice is and will always be a key issue in urban design. As previously mentioned, past urban strategies have caused injustices within communities incapable of being remedied via simple means. As urban designers tackle the issue of justice, they often are required to look at the injustices of the past and must be careful not to overlook the nuances of race, place, and socioeconomic status in their design efforts. This includes ensuring reasonable access to basic services, transportation, and fighting against gentrification and the commodification of space for economic gain. Organizations such as the Divided Cities Initiatives at Washington University in St. Louis and the Just City Lab at Harvard work on promoting justice in urban design.

Until the 1970s, the design of towns and cities took little account of the needs of people with disabilities. At that time, disabled people began to form movements demanding recognition of their potential contribution if social obstacles were removed. Disabled people challenged the 'medical model' of disability which saw physical and mental problems as an individual 'tragedy' and people with disabilities as 'brave' for enduring them. They proposed instead a 'social model' which said that barriers to disabled people result from the design of the built environment and attitudes of able-bodied people. 'Access Groups' were established composed of people with disabilities who audited their local areas, checked planning applications, and made representations for improvements. The new profession of 'access officer' was established around that time to produce guidelines based on the recommendations of access groups and to oversee adaptations to existing buildings as well as to check on the accessibility of new proposals. Many local authorities now employ access officers who are regulated by the Access Association. A new chapter of the Building Regulations (Part M) was introduced in 1992. Although it was beneficial to have legislation on this issue the requirements were fairly minimal but continue to be improved with ongoing amendments. The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 continues to raise awareness and enforce action on disability issues in the urban environment.