From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An

oligopoly (

, from Ancient Greek

ὀλίγος (olígos) "few" +

πωλεῖν (poleîn) "to sell") is a

market form wherein a

market or

industry

is dominated by a small number of large sellers (oligopolists).

Oligopolies can result from various forms of collusion which reduce

competition and lead to higher prices for consumers. Oligopolies have

their own market structure.

With few sellers, each oligopolist is likely to be aware of the actions of the others. According to

game theory, the decisions of one firm therefore influence and are influenced by decisions of other firms.

Strategic planning by oligopolists needs to take into account the likely responses of the other market. Entry barriers include high

investment requirements, strong

consumer loyalty for existing brands and

economies of scale.

Description

Oligopoly

is a common market form where a number of firms are in competition. As a

quantitative description of oligopoly, the four-firm

concentration ratio

is often utilized. This measure expresses, as a percentage, the market

share of the four largest firms in any particular industry. For example,

as of fourth quarter 2008, if we combine total market share of Verizon

Wireless, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile, we see that these firms,

together, control 97% of the U.S. cellular telephone market.

Oligopolistic

competition

can give rise to both wide-ranging and diverse outcomes. In some

situations, particular companies may employ restrictive trade practices (

collusion, market sharing etc.) in order to inflate prices and restrict production in much the same way that a

monopoly

does. Whenever there is a formal agreement for such collusion, between

companies that usually compete with one another, this practice is known

as a

cartel. A prime example of such a cartel is

OPEC, which has a profound influence on the international price of oil.

Firms often collude in an attempt to stabilize unstable markets,

so as to reduce the risks inherent in these markets for investment and

product development.

There are legal restrictions on such collusion in most countries. There

does not have to be a formal agreement for collusion to take place

(although for the act to be illegal there must be actual communication

between companies)–for example, in some industries there may be an

acknowledged market leader which informally sets prices to which other

producers respond, known as

price leadership.

In other situations, competition between sellers in an oligopoly

can be fierce, with relatively low prices and high production. This

could lead to an efficient outcome approaching

perfect competition.

The competition in an oligopoly can be greater when there are more

firms in an industry than if, for example, the firms were only

regionally based and did not compete directly with each other.

Thus the

welfare

analysis of oligopolies is sensitive to the parameter values used to

define the market's structure. In particular, the level of

dead weight loss is hard to measure. The study of

product differentiation indicates that oligopolies might also create excessive levels of differentiation in order to stifle competition.

Oligopoly theory makes heavy use of

game theory to model the behavior of oligopolies:

- Stackelberg's duopoly. In this model, the firms move sequentially.

- Cournot's duopoly. In this model, the firms simultaneously choose quantities.

- Bertrand's oligopoly. In this model, the firms simultaneously choose prices.

Characteristics

- Profit maximization conditions

- An oligopoly maximizes profits.

- Ability to set price

- Oligopolies are price setters rather than price takers.

- Entry and exit

- Barriers to entry are high.

The most important barriers are government licenses, economies of

scale, patents, access to expensive and complex technology, and

strategic actions by incumbent firms designed to discourage or destroy

nascent firms. Additional sources of barriers to entry often result from

government regulation favoring existing firms making it difficult for

new firms to enter the market.

- Number of firms

- "Few" – a "handful" of sellers. There are so few firms that the actions of one firm can influence the actions of the other firms.

- Long run profits

- Oligopolies can retain long run abnormal profits. High barriers of

entry prevent sideline firms from entering market to capture excess

profits.

- Product differentiation

- Product may be homogeneous (steel) or differentiated (automobiles).

- Perfect knowledge

- Assumptions about perfect knowledge

vary but the knowledge of various economic factors can be generally

described as selective. Oligopolies have perfect knowledge of their own

cost and demand functions but their inter-firm information may be

incomplete. Buyers have only imperfect knowledge as to price, cost and product quality.

- Interdependence

- The distinctive feature of an oligopoly is interdependence.

Oligopolies are typically composed of a few large firms. Each firm is

so large that its actions affect market conditions. Therefore, the

competing firms will be aware of a firm's market actions and will

respond appropriately. This means that in contemplating a market action,

a firm must take into consideration the possible reactions of all

competing firms and the firm's countermoves. It is very much like a game of chess,

in which a player must anticipate a whole sequence of moves and

countermoves in order to determine how to achieve his or her objectives;

this is known as game theory.

For example, an oligopoly considering a price reduction may wish to

estimate the likelihood that competing firms would also lower their

prices and possibly trigger a ruinous price war. Or if the firm is

considering a price increase, it may want to know whether other firms

will also increase prices or hold existing prices constant. This

anticipation leads to price rigidity as firms will be only be willing to

adjust their prices and quantity of output in accordance with a "price

leader" in the market. This high degree of interdependence and need to

be aware of what other firms are doing or might do is to be contrasted

with lack of interdependence in other market structures. In a perfectly competitive (PC) market there is zero interdependence because no firm is large enough to affect market price. All firms in a PC

market are price takers, as current market selling price can be

followed predictably to maximize short-term profits. In a monopoly,

there are no competitors to be concerned about. In a monopolistically-competitive market, each firm's effects on market conditions is so negligible as to be safely ignored by competitors.

- Non-Price Competition

- Oligopolies tend to compete on terms other than price. Loyalty

schemes, advertisement, and product differentiation are all examples of

non-price competition.

Oligopolies in countries with competition laws

Oligopolies

become "mature" when they realise they can profit maximise through

joint profit maximising. As a result of operating in countries with

enforced competition laws, the Oligopolists will operate under tacit

collusion, which is collusion through an understanding that if all the

competitors in the market raise their prices, then collectively all the

competitors can achieve economic profits close to a monopolist, without

evidence of breaching government market regulations. Hence, the kinked

demand curve for a joint profit maximising Oligopoly industry can model

the behaviours of oligopolists pricing decisions other than that of the

price leader (the price leader being the firm that all other firms

follow in terms of pricing decisions). This is because if a firm

unilaterally raises the prices of their good/service, and other

competitors do not follow then, the firm that raised their price will

then lose a significant market as they face the elastic upper segment of

the demand curve. As the joint profit maximising achieves greater

economic profits for all the firms, there is an incentive for an

individual firm to "cheat" by expanding output to gain greater market

share and profit. In Oligopolist cheating, and the incumbent firm

discovering this breach in collusion, the other firms in the market will

retaliate by matching or dropping prices lower than the original drop.

Hence, the market share that the firm that dropped the price gained,

will have that gain minimised or eliminated. This is why on the kinked

demand curve model the lower segment of the demand curve is inelastic.

As a result, price rigidity prevails in such markets.

Modeling

There is no single model describing the operation of an oligopolistic market.

The variety and complexity of the models exist because you can have two

to 10 firms competing on the basis of price, quantity, technological

innovations, marketing, and reputation. However, there are a series of

simplified models that attempt to describe market behavior by

considering certain circumstances. Some of the better-known models are

the

dominant firm model, the

Cournot–Nash model, the

Bertrand model and the

kinked demand model.

Cournot–Nash model

The

Cournot–

Nash

model is the simplest oligopoly model. The model assumes that there are

two "equally positioned firms"; the firms compete on the basis of

quantity rather than price and each firm makes an "output of decision

assuming that the other firm's behavior is fixed."

The market demand curve is assumed to be linear and marginal costs are

constant. To find the Cournot–Nash equilibrium one determines how each

firm reacts to a change in the output of the other firm. The path to

equilibrium is a series of actions and reactions. The pattern continues

until a point is reached where neither firm desires "to change what it

is doing, given how it believes the other firm will react to any

change."

The equilibrium is the intersection of the two firm's reaction

functions. The reaction function shows how one firm reacts to the

quantity choice of the other firm. For example, assume that the firm 1's demand function is

P = (

M −

Q2) −

Q1 where

Q2 is the quantity produced by the other firm and Q

1 is the amount produced by firm 1, and M=60 is the market. Assume that marginal cost is C

M=12.

Firm 1 wants to know its maximizing quantity and price. Firm 1 begins

the process by following the profit maximization rule of equating

marginal revenue to marginal costs. Firm 1's total revenue function is

RT =

Q1 P =

Q1(

M −

Q2 −

Q1) =

MQ1 −

Q1 Q2 −

Q12. The marginal revenue function is

.

- RM = CM

- M − Q2 − 2Q1 = CM

- 2Q1 = (M − CM) − Q2

- Q1 = (M − CM)/2 − Q2/2 = 24 − 0.5 Q2 [1.1]

- Q2 = 2(M − CM) − 2Q1 = 96 − 2 Q1 [1.2]

Equation 1.1 is the reaction function for firm 1. Equation 1.2 is the reaction function for firm 2.

To determine the Cournot–Nash equilibrium you can solve the

equations simultaneously. The equilibrium quantities can also be

determined graphically. The equilibrium solution would be at the

intersection of the two reaction functions. Note that if you graph the

functions the axes represent quantities. The reaction functions are not necessarily symmetric.

The firms may face differing cost functions in which case the reaction

functions would not be identical nor would the equilibrium quantities.

Bertrand model

The Bertrand model is essentially the Cournot–Nash model except the strategic variable is price rather than quantity.

The model assumptions are:

- There are two firms in the market

- They produce a homogeneous product

- They produce at a constant marginal cost

- Firms choose prices PA and PB simultaneously

- Firms outputs are perfect substitutes

- Sales are split evenly if PA = PB

The only Nash equilibrium is PA = PB = MC.

Neither firm has any reason to change strategy. If the firm

raises prices it will lose all its customers. If the firm lowers price P

< MC then it will be losing money on every unit sold.

The Bertrand equilibrium is the same as the competitive result. Each firm will produce where P = marginal costs and there will be zero profits. A generalization of the Bertrand model is the

Bertrand–Edgeworth model that allows for capacity constraints and more general cost functions.

Oligopolistic market Kinked demand curve model

According to this model, each firm faces a demand curve kinked at the existing price.

The conjectural assumptions of the model are; if the firm raises its

price above the current existing price, competitors will not follow and

the acting firm will lose market share and second if a firm lowers

prices below the existing price then their competitors will follow to

retain their market share and the firm's output will increase only

marginally.

If the assumptions hold then:

- The firm's marginal revenue curve is discontinuous (or rather, not differentiable), and has a gap at the kink

- For prices above the prevailing price the curve is relatively elastic

- For prices below the point the curve is relatively inelastic

The gap in the marginal revenue curve means that marginal costs can fluctuate without changing equilibrium price and quantity. Thus prices tend to be rigid.

Examples

In industrialized economies,

barriers to entry have resulted in oligopolies forming in many sectors, with unprecedented levels of competition fueled by increasing

globalization.

Market shares in an oligopoly are typically determined by product

development and advertising. For example, there are now only a small

number of manufacturers of civil passenger aircraft, though Brazil (

Embraer) and Canada (

Bombardier)

have participated in the small passenger aircraft market sector.

Oligopolies have also arisen in heavily-regulated markets such as

wireless communications: in some areas only two or three providers are

licensed to operate.

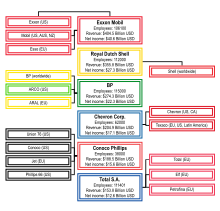

Worldwide

Aircraft

Finance

Food

Technology

Australia

Canada

Media

Other

- Five companies dominate the banking industry: Royal Bank of Canada, Toronto Dominion Bank, Bank of Nova Scotia, Bank of Montreal, and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce

- As of 2008 Rogers Wireless, Bell Mobility and Telus Mobility control a combined 94% of Canada's wireless telecommunications market

- Rogers Communications, Bell Canada, Telus, and Shaw Communications dominate the internet service provider market

- Husky Energy, Imperial Oil, Nexen, Shell Canada, Suncor Energy, Syncrude, and Repsol Oil & Gas Canada dominate the oil and gas sector

India

European Union

- The VHF Data Link market as air-ground part of aeronautical communications is controlled by ARINC and SITA,

commonly known as the organisations providing communication services

for the exchange of data between air-ground applications in the

Commission Regulation (EC) No 29/2009.

United Kingdom

- Five banks (Barclays, Halifax, HSBC, Lloyds TSB and Natwest) dominate the UK banking sector, they were accused of being an oligopoly by the relative newcomer Virgin Money.

- Four companies (Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda and Morrisons) share 74.4% of the grocery market.

- The detergent market is dominated by two players, Unilever and Procter & Gamble.

- Six utilities (EDF Energy, Centrica, RWE npower, E.on, Scottish Power and Scottish and Southern Energy) share 95% of the retail electricity market.

- Four mobile phone networks. Virtual mobile networks like Tesco Mobile have attempted to broaden the market, but there are still just four core network providers in EE, Vodafone, O2 and 3 Mobile.

- Big Four Accounting Firms- (KPMG, PWC, Ernst and Young and Deloitte) These four firms audit 99% of the companies in the FTSE100 and 96% of the companies in the FTSE 250 Index.

United States

Media

- Six movie studios (Walt Disney Pictures, Sony Pictures, Universal Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures, Warner Bros. Entertainment) receive almost 87% of American film revenues.

- The television and high speed internet industry is mostly an oligopoly of seven companies: The Walt Disney Company, CBS Corporation, Viacom, Comcast, Hearst Corporation, Time Warner, and News Corporation (now 21st Century Fox and News Corp). See Concentration of media ownership.

- In March 2012, the United States Department of Justice

announced that it would sue six major publishers for price fixing in

the sale of electronic books. The accused publishers are Apple, Simon

& Schuster Inc, Hachette Book Group, Penguin Group, Macmillan, and

HarperCollins Publishers.

Other

- Four wireless providers (AT&T Mobility, Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile, Sprint Corporation) control 89% of the cellular telephone service market.

This is not to be confused with cellular telephone manufacturing, an

integral portion of the cellular telephone market as a whole.

- Healthcare insurance in the United States

consists of very few insurance companies controlling major market share

in most states. For example, California's insured population of 20

million is the most competitive in the nation and 44% of that market is dominated by two insurance companies, Anthem and Kaiser Permanente.

- Mergers among airlines have left the industry in the United States dominated by four main entities – Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Southwest Airlines and American Airlines – which purposely do not compete on some air travel routes.

- Transcontinental freight lines are vastly controlled by two railroads: Union Pacific Railroad and BNSF Railroad.

- The big box retail industry in the U.S. is dominated by Walmart, Target, and Costco.

- Walgreens and CVS Pharmacy take up 86% of the U.S. pharmacy market.

Demand curve

Above

the kink, demand is relatively elastic because all other firms' prices

remain unchanged. Below the kink, demand is relatively inelastic because

all other firms will introduce a similar price cut, eventually leading

to a price war. Therefore, the best option for the oligopolist is to produce at point E

which is the equilibrium point and the kink point. This is a

theoretical model proposed in 1947, which has failed to receive

conclusive evidence for support.

"Kinked" demand curves are similar to traditional demand curves,

as they are downward-sloping. They are distinguished by a hypothesized

convex bend with a discontinuity at the bend–"kink". Thus the first

derivative at that point is undefined and leads to a jump discontinuity in the

marginal revenue curve.

Classical

economic theory assumes that a profit-maximizing producer with some market power (either due to oligopoly or

monopolistic competition)

will set marginal costs equal to marginal revenue. This idea can be

envisioned graphically by the intersection of an upward-sloping marginal

cost curve and a downward-sloping marginal revenue curve (because the

more one sells, the lower the price must be, so the less a producer

earns per unit). In classical theory, any change in the marginal cost

structure (how much it costs to make each additional unit) or the

marginal revenue structure (how much people will pay for each additional

unit) will be immediately reflected in a new price and/or quantity sold

of the item. This result does not occur if a "kink" exists. Because of

this jump discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve,

marginal costs could change without necessarily changing the price or quantity.

The motivation behind this kink is the idea that in an

oligopolistic or monopolistically competitive market, firms will not

raise their prices because even a small price increase will lose many

customers. This is because competitors will generally ignore price

increases, with the hope of gaining a larger market share as a result of

now having comparatively lower prices. However, even a large price

decrease will gain only a few customers because such an action will

begin a

price war with other firms. The curve is therefore more

price-elastic for price increases and less so for price decreases. Theory predicts that firms will enter the industry in the long run.