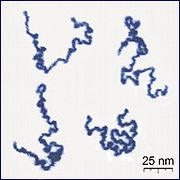

Appearance of real linear polymer chains as recorded using an atomic force microscope on a surface, under liquid medium. Chain contour length for this polymer is ~204 nm; thickness is ~0.4 nm.

Polymer is a substance composed of macromolecules (synonym: polymer molecules).

Macromolecule = A molecule of high relative molecular mass, the

structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of

units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative

molecular mass.

A polymer (/ˈpɒlɪmər/; Greek poly-, "many" + -mer, "part") is a large molecule, or macromolecule, composed of many repeated subunits. Due to their broad range of properties, both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life. Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function. Polymers, both natural and synthetic, are created via polymerization of many small molecules, known as monomers. Their consequently large molecular mass relative to small molecule compounds produces unique physical properties, including toughness, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form glasses and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals. The terms polymer and resin are often synonymous with plastic.

The term "polymer" derives from the Greek word πολύς (polus, meaning "many, much") and μέρος (meros, meaning "part"), and refers to a molecule whose structure is composed of multiple repeating units, from which originates a characteristic of high relative molecular mass and attendant properties. The units composing polymers derive, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass. The term was coined in 1833 by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, though with a definition distinct from the modern IUPAC definition. The modern concept of polymers as covalently bonded macromolecular structures was proposed in 1920 by Hermann Staudinger, who spent the next decade finding experimental evidence for this hypothesis.

Polymers are studied in the fields of biophysics and macromolecular science, and polymer science (which includes polymer chemistry and polymer physics). Historically, products arising from the linkage of repeating units by covalent chemical bonds have been the primary focus of polymer science; emerging important areas of the science now focus on non-covalent links. Polyisoprene of latex rubber is an example of a natural/biological polymer, and the polystyrene of styrofoam is an example of a synthetic polymer. In biological contexts, essentially all biological macromolecules—i.e., proteins (polyamides), nucleic acids

(polynucleotides), and polysaccharides—are purely polymeric, or are

composed in large part of polymeric components—e.g.,

isoprenylated/lipid-modified glycoproteins, where small lipidic

molecules and oligosaccharide modifications occur on the polyamide backbone of the protein.

The simplest theoretical models for polymers are ideal chains.

Common examples

Polymers are of two types: naturally occurring and synthetic or man made. (DJS: I would say free-radical and condensation.)

Natural polymeric materials such as hemp, shellac, amber, wool, silk and natural rubber have been used for centuries. A variety of other natural polymers exist, such as cellulose, which is the main constituent of wood and paper.

The list of synthetic polymers, roughly in order of worldwide demand, includes polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, synthetic rubber, phenol formaldehyde resin (or Bakelite), neoprene, nylon, polyacrylonitrile, PVB, silicone, and many more. More than 330 million tons of these polymers are made every year (2015).

Most commonly, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms. A simple example is polyethylene ('polythene' in British English), whose repeating unit is based on ethylene monomer.

However, other structures do exist; for example, elements such as

silicon form familiar materials such as silicones, examples being Silly Putty and waterproof plumbing sealant. Oxygen is also commonly present in polymer backbones, such as those of polyethylene glycol, polysaccharides (in glycosidic bonds), and DNA (in phosphodiester bonds).

Synthesis

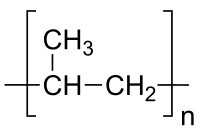

The repeating unit of the polymer polypropylene

Polymerization is the process of combining many small molecules

known as monomers into a covalently bonded chain or network. During the

polymerization process, some chemical groups may be lost from each

monomer. This is the case, for example, in the polymerization of PET polyester. The monomers are terephthalic acid (HOOC—C6H4—COOH) and ethylene glycol (HO—CH2—CH2—OH) but the repeating unit is —OC—C6H4—COO—CH2—CH2—O—,

which corresponds to the combination of the two monomers with the loss

of two water molecules. The distinct piece of each monomer that is

incorporated into the polymer is known as a repeat unit or monomer residue.

Laboratory synthetic methods are generally divided into two categories, step-growth polymerization and chain-growth polymerization.

The essential difference between the two is that in chain growth

polymerization, monomers are added to the chain one at a time only, such as in polyethylene, whereas in step-growth polymerization chains of monomers may combine with one another directly, such as in polyester. However, some newer methods such as plasma polymerization do not fit neatly into either category. Synthetic polymerization reactions may be carried out with or without a catalyst. Laboratory synthesis of biopolymers, especially of proteins, is an area of intensive research.

Biological synthesis

Microstructure of part of a DNA double helix biopolymer

There are three main classes of biopolymers: polysaccharides, polypeptides, and polynucleotides.

In living cells, they may be synthesized by enzyme-mediated processes, such as the formation of DNA catalyzed by DNA polymerase. The synthesis of proteins involves multiple enzyme-mediated processes to transcribe genetic information from the DNA to RNA and subsequently translate that information to synthesize the specified protein from amino acids. The protein may be modified further following translation in order to provide appropriate structure and functioning. There are other biopolymers such as rubber, suberin, melanin and lignin.

Modification of natural polymers

Naturally

occurring polymers such as cotton, starch and rubber were familiar

materials for years before synthetic polymers such as polyethene and perspex

appeared on the market.

Many commercially important polymers are synthesized by chemical

modification of naturally occurring polymers. Prominent examples include

the reaction of nitric acid and cellulose to form nitrocellulose and the formation of vulcanized rubber by heating natural rubber in the presence of sulfur.

Ways in which polymers can be modified include oxidation, cross-linking and endcapping.

Especially in the production of polymers the gas separation by membranes has acquired increasing importance in the petrochemical industry

and is now a relatively well-established unit operation.

The process of polymer degassing is necessary to suit polymer for

extrusion and pelletizing, increasing safety, environmental, and product

quality aspects. Nitrogen is generally used for this purpose, resulting

in a vent gas primarily composed of monomers and nitrogen.

Properties

Polymer

properties are broadly divided into several classes based on the scale

at which the property is defined as well as upon its physical basis. The most basic property of a polymer is the identity of its constituent monomers. A second set of properties, known as microstructure,

essentially describes the arrangement of these monomers within the

polymer at the scale of a single chain. These basic structural

properties play a major role in determining bulk physical properties of

the polymer, which describe how the polymer behaves as a continuous

macroscopic material. Chemical properties, at the nano-scale, describe

how the chains interact through various physical forces. At the

macro-scale, they describe how the bulk polymer interacts with other

chemicals and solvents.

Monomers and repeat units

The

identity of the repeat units (monomer residues, also known as "mers")

comprising a polymer is its first and most important attribute. Polymer

nomenclature is generally based upon the type of monomer residues

comprising the polymer. Polymers that contain only a single type of

repeat unit are known as homopolymers, while polymers containing two or

more types of repeat units are known as copolymers. Terpolymers contain three types of repeat units.

Poly(styrene), for example, is composed only of styrene monomer residues, and is therefore classified as a homopolymer. Ethylene-vinyl acetate,

on the other hand, contains more than one variety of repeat unit and is

thus a copolymer. Some biological polymers are composed of a variety of

different but structurally related monomer residues; for example, polynucleotides such as DNA are composed of four types of nucleotide subunits.

A polymer molecule containing ionizable subunits is known as a polyelectrolyte or ionomer.

Microstructure

The microstructure of a polymer (sometimes called configuration)

relates to the physical arrangement of monomer residues along the

backbone of the chain.

These are the elements of polymer structure that require the breaking

of a covalent bond in order to change. Structure has a strong influence

on the other properties of a polymer. For example, two samples of

natural rubber may exhibit different durability, even though their

molecules comprise the same monomers.

Polymer architecture

Branch point in a polymer

An important microstructural feature of a polymer is its architecture

and shape, which relates to the way branch points lead to a deviation

from a simple linear chain. A branched polymer molecule is composed of a main chain with one or more substituent side chains or branches. Types of branched polymers include star polymers, comb polymers, brush polymers, dendronized polymers, ladder polymers, and dendrimers. There exist also two-dimensional polymers

which are composed of topologically planar repeat units. A polymer's

architecture affects many of its physical properties including, but not

limited to, solution viscosity, melt viscosity, solubility in various

solvents, glass transition temperature and the size of individual

polymer coils in solution. A variety of techniques may be employed for

the synthesis of a polymeric material with a range of architectures, for

example living polymerization.

Chain length

A common means of expressing the length of a chain is the degree of polymerization, which quantifies the number of monomers incorporated into the chain. As with other molecules, a polymer's size may also be expressed in terms of molecular weight.

Since synthetic polymerization techniques typically yield a statistical

distribution of chain lengths, the molecular weight is expressed in

terms of weighted averages. The number-average molecular weight (Mn) and weight-average molecular weight (Mw) are most commonly reported. The ratio of these two values (Mw / Mn) is the dispersity (Đ), which is commonly used to express the width of the molecular weight distribution.

The physical properties of polymer strongly depend on the length (or equivalently, the molecular weight) of the polymer chain. One important example of the physical consequences of the molecular weight is the scaling of the viscosity (resistance to flow) in the melt. The influence of the weight-average molecular weight (Mw) on the melt viscosity (η) depends on whether the polymer is above or below the onset of entanglements. Below the entanglement molecular weight, , whereas above the entanglement molecular weight, . In the latter case, increasing the polymer chain length 10-fold would increase the viscosity over 1000 times. Increasing chain length furthermore tends to decrease chain mobility, increase strength and toughness, and increase the glass transition temperature (Tg). This is a result of the increase in chain interactions such as Van der Waals attractions and entanglements that come with increased chain length.

These interactions tend to fix the individual chains more strongly in

position and resist deformations and matrix breakup, both at higher

stresses and higher temperatures.

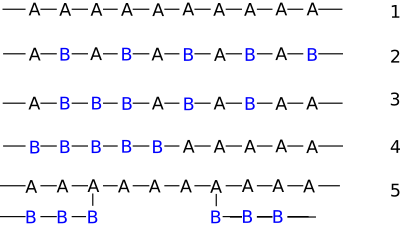

Monomer arrangement in copolymers

Monomers within a copolymer may be organized along the backbone in a

variety of ways. A copolymer containing a controlled arrangement of

monomers is called a sequence-controlled polymer. Alternating, periodic and block copolymers are simple examples of sequence-controlled polymers.

- Alternating copolymers possess two regularly alternating monomer residues: [AB]n (structure 2 at right). An example is the equimolar copolymer of styrene and maleic anhydride formed by free-radical chain-growth polymerization. A step-growth copolymer such as Nylon 66 can also be considered a strictly alternating copolymer of diamine and diacid residues, but is often described as a homopolymer with the dimeric residue of one amine and one acid as a repeat unit.

- Periodic copolymers have monomer residue types arranged in a repeating sequence: [AnBm...] m being different from n.

- Statistical copolymers have monomer residues arranged according to a statistical rule. A statistical copolymer in which the probability of finding a particular type of monomer residue at a particular point in the chain is independent of the types of surrounding monomer residue may be referred to as a truly random copolymer (structure 3). For example, the chain-growth copolymer of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate is random.

- Block copolymers have long sequences of different monomer units (structure 4). Polymers with two or three blocks of two distinct chemical species (e.g., A and B) are called diblock copolymers and triblock copolymers, respectively. Polymers with three blocks, each of a different chemical species (e.g., A, B, and C) are termed triblock terpolymers.

- Graft or grafted copolymers contain side chains or branches whose repeat units have a different composition or configuration than the main chain. (structure 5) The branches are added on to a preformed main chain macromolecule.

Tacticity

Tacticity describes the relative stereochemistry of chiral centers in neighboring structural units within a macromolecule. There are three types of tacticity: isotactic (all substituents on the same side), atactic (random placement of substituents), and syndiotactic (alternating placement of substituents).

Morphology

Polymer morphology generally describes the arrangement and microscale ordering of polymer chains in space.

Crystallinity

When applied to polymers, the term crystalline has a somewhat ambiguous usage. In some cases, the term crystalline finds identical usage to that used in conventional crystallography. For example, the structure of a crystalline protein or polynucleotide, such as a sample prepared for x-ray crystallography,

may be defined in terms of a conventional unit cell composed of one or

more polymer molecules with cell dimensions of hundreds of angstroms

or more. A synthetic polymer may be loosely described as crystalline if

it contains regions of three-dimensional ordering on atomic (rather

than macromolecular) length scales, usually arising from intramolecular

folding and/or stacking of adjacent chains. Synthetic polymers may

consist of both crystalline and amorphous regions; the degree of

crystallinity may be expressed in terms of a weight fraction or volume

fraction of crystalline material. Few synthetic polymers are entirely

crystalline.

The crystallinity of polymers is characterized by their degree of

crystallinity, ranging from zero for a completely non-crystalline

polymer to one for a theoretical completely crystalline polymer.

Polymers with microcrystalline regions are generally tougher (can be

bent more without breaking) and more impact-resistant than totally

amorphous polymers.

Polymers with a degree of crystallinity approaching zero or one will

tend to be transparent, while polymers with intermediate degrees of

crystallinity will tend to be opaque due to light scattering by

crystalline or glassy regions. Thus for many polymers, reduced

crystallinity may also be associated with increased transparency.

Chain conformation

The space occupied by a polymer molecule is generally expressed in terms of radius of gyration,

which is an average distance from the center of mass of the chain to

the chain itself. Alternatively, it may be expressed in terms of pervaded volume, which is the volume of solution spanned by the polymer chain and scales with the cube of the radius of gyration.

Mechanical properties

A polyethylene sample that has necked under tension.

The bulk properties of a polymer are those most often of end-use

interest. These are the properties that dictate how the polymer actually

behaves on a macroscopic scale.

Tensile strength

The tensile strength of a material quantifies how much elongating stress the material will endure before failure.

This is very important in applications that rely upon a polymer's

physical strength or durability. For example, a rubber band with a

higher tensile strength will hold a greater weight before snapping. In

general, tensile strength increases with polymer chain length and crosslinking of polymer chains.

Young's modulus of elasticity

Young's modulus quantifies the elasticity of the polymer.. It is defined, for small strains,

as the ratio of rate of change of stress to strain. Like tensile

strength, this is highly relevant in polymer applications involving the

physical properties of polymers, such as rubber bands. The modulus is

strongly dependent on temperature. Viscoelasticity describes a complex time-dependent elastic response, which will exhibit hysteresis in the stress-strain curve when the load is removed. Dynamic mechanical analysis or DMA measures this complex modulus by oscillating the load and measuring the resulting strain as a function of time.

Transport properties

Transport

properties such as diffusivity relate to how rapidly molecules move

through the polymer matrix. These are very important in many

applications of polymers for films and membranes.

Phase behavior

Crystallization and melting

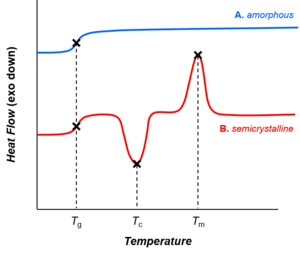

Thermal transitions in (A) amorphous and (B) semicrystalline polymers, represented as traces from differential scanning calorimetry. As the temperature increases, both amorphous and semicrystalline polymers go through the glass transition (Tg). Amorphous polymers (A) do not exhibit other phase transitions. However, semicrystalline polymers (B) undergo crystallization and melting (at temperatures Tc and Tm, respectively).

Depending on their chemical structures, polymers may be either

semi-crystalline or amorphous. Semi-crystalline polymers can undergo crystallization and melting transitions,

whereas amorphous polymers do not. In polymers, crystallization and

melting do not suggest solid-liquid phase transitions, as in the case of

water or other molecular fluids. Instead, crystallization and melting

refer to the phase transitions between two solid states (i.e., semi-crystalline and amorphous). Crystallization occurs above the glass transition temperature (Tg) and below the melting temperature (Tm).

Glass transition

All polymers (amorphous or semi-crystalline) go through glass transitions. The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a crucial physical parameter for polymer manufacturing, processing, and use. Below Tg, molecular motions are frozen and polymers are brittle and glassy. Above Tg,

molecular motions are activated and polymers are rubbery and viscous.

The glass transition temperature may be engineered by altering the

degree of branching or crosslinking in the polymer or by the addition of

plasticizers.

Whereas crystallization and melting are first-order phase transitions, the glass transition is not.

The glass transition shares features of second-order phase transitions

(such as discontinuity in the heat capacity, as shown in the figure),

but it is generally not considered a thermodynamic transition between

equilibrium states.

Mixing behavior

In general, polymeric mixtures are far less miscible than mixtures of small molecule materials. This effect results from the fact that the driving force for mixing is usually entropy,

not interaction energy. In other words, miscible materials usually form

a solution not because their interaction with each other is more

favorable than their self-interaction, but because of an increase in

entropy and hence free energy associated with increasing the amount of

volume available to each component. This increase in entropy scales with

the number of particles (or moles) being mixed. Since polymeric

molecules are much larger and hence generally have much higher specific

volumes than small molecules, the number of molecules involved in a

polymeric mixture is far smaller than the number in a small molecule

mixture of equal volume. The energetics of mixing, on the other hand, is

comparable on a per volume basis for polymeric and small molecule

mixtures. This tends to increase the free energy of mixing for polymer

solutions and thus make solvation less favorable. Thus, concentrated

solutions of polymers are far rarer than those of small molecules.

Furthermore, the phase behavior of polymer solutions and mixtures

is more complex than that of small molecule mixtures. Whereas most

small molecule solutions exhibit only an upper critical solution temperature phase transition, at which phase separation occurs with cooling, polymer mixtures commonly exhibit a lower critical solution temperature phase transition, at which phase separation occurs with heating.

In dilute solution, the properties of the polymer are

characterized by the interaction between the solvent and the polymer. In

a good solvent, the polymer appears swollen and occupies a large

volume. In this scenario, intermolecular forces between the solvent and

monomer subunits dominate over intramolecular interactions. In a bad

solvent or poor solvent, intramolecular forces dominate and the chain

contracts. In the theta solvent,

or the state of the polymer solution where the value of the second

virial coefficient becomes 0, the intermolecular polymer-solvent

repulsion balances exactly the intramolecular monomer-monomer

attraction. Under the theta condition (also called the Flory condition), the polymer behaves like an ideal random coil. The transition between the states is known as a coil-globule transition.

Inclusion of plasticizers

Inclusion of plasticizers tends to lower Tg

and increase polymer flexibility. Plasticizers are generally small

molecules that are chemically similar to the polymer and create gaps

between polymer chains for greater mobility and reduced interchain

interactions. A good example of the action of plasticizers is related to

polyvinylchlorides or PVCs. An uPVC, or unplasticized

polyvinylchloride, is used for things such as pipes. A pipe has no

plasticizers in it, because it needs to remain strong and

heat-resistant. Plasticized PVC is used in clothing for a flexible

quality. Plasticizers are also put in some types of cling film to make

the polymer more flexible.

Chemical properties

The

attractive forces between polymer chains play a large part in

determining polymer's properties. Because polymer chains are so long,

these interchain forces are amplified far beyond the attractions between

conventional molecules. Different side groups on the polymer can lend

the polymer to ionic bonding or hydrogen bonding

between its own chains. These stronger forces typically result in

higher tensile strength and higher crystalline melting points.

The intermolecular forces in polymers can be affected by dipoles in the monomer units. Polymers containing amide or carbonyl groups can form hydrogen bonds

between adjacent chains; the partially positively charged hydrogen

atoms in N-H groups of one chain are strongly attracted to the partially

negatively charged oxygen atoms in C=O groups on another. These strong

hydrogen bonds, for example, result in the high tensile strength and

melting point of polymers containing urethane or urea linkages. Polyesters have dipole-dipole bonding

between the oxygen atoms in C=O groups and the hydrogen atoms in H-C

groups. Dipole bonding is not as strong as hydrogen bonding, so a

polyester's melting point and strength are lower than Kevlar's (Twaron), but polyesters have greater flexibility.

Ethene, however, has no permanent dipole. The attractive forces between polyethylene chains arise from weak van der Waals forces.

Molecules can be thought of as being surrounded by a cloud of negative

electrons. As two polymer chains approach, their electron clouds repel

one another. This has the effect of lowering the electron density on one

side of a polymer chain, creating a slight positive dipole on this

side. This charge is enough to attract the second polymer chain. Van der

Waals forces are quite weak, however, so polyethylene can have a lower

melting temperature compared to other polymers.

Optical properties

Polymers such as PMMA and HEMA:MMA are used as matrices in the gain medium of solid-state dye lasers

that are also known as polymer lasers. These polymers have a high

surface quality and are also highly transparent so that the laser

properties are dominated by the laser dye used to dope the polymer matrix. These type of lasers, that also belong to the class of organic lasers, are known to yield very narrow linewidths which is useful for spectroscopy and analytical applications. An important optical parameter in the polymer used in laser applications is the change in refractive index with temperature

also known as dn/dT. For the polymers mentioned here the (dn/dT) ~ −1.4 × 10−4 in units of K−1 in the 297 ≤ T ≤ 337 K range.

Standardized nomenclature

There

are multiple conventions for naming polymer substances. Many commonly

used polymers, such as those found in consumer products, are referred to

by a common or trivial name. The trivial name is assigned based on

historical precedent or popular usage rather than a standardized naming

convention. Both the American Chemical Society (ACS) and IUPAC have proposed standardized naming conventions; the ACS and IUPAC conventions are similar but not identical. Examples of the differences between the various naming conventions are given in the table below:

| Common name | ACS name | IUPAC name |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene oxide) or PEO | Poly(oxyethylene) | Poly(oxyethene) |

| Poly(ethylene terephthalate) or PET | Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyloxycarbonyl-1,4-phenylenecarbonyl) | Poly(oxyetheneoxyterephthaloyl) |

| Nylon 6 | Poly[amino(1-oxo-1,6-hexanediyl)] | Poly[amino(1-oxohexan-1,6-diyl)] |

In both standardized conventions, the polymers' names are intended to

reflect the monomer(s) from which they are synthesized rather than the

precise nature of the repeating subunit. For example, the polymer

synthesized from the simple alkene ethene is called polyethylene, retaining the -ene suffix even though the double bond is removed during the polymerization process:

Characterization

Polymer characterization spans many techniques for determining the

chemical composition, molecular weight distribution, and physical

properties. Select common techniques include the following:

- Size-exclusion chromatography (also called gel permeation chromatography), sometimes coupled with static light scattering, can used to determine the number-average molecular weight, weight-average molecular weight, and dispersity.

- Scattering techniques, such as static light scattering and small-angle neutron-scattering, are used to determine the dimensions (radius of gyration) of macromolecules in solution or in the melt. These techniques are also used to characterize the three-dimensional structure of microphase-separated block polymers, polymeric micelles, and other materials.

- Wide-angle X-ray scattering (also called wide-angle X-ray diffraction) is used to determine the crystalline structure of polymers (or lack thereof).

- Spectroscopy techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, can be used to determine the chemical composition.

- Differential scanning calorimetry is used to characterize the thermal properties of polymers, such as the glass transition temperature, crystallization temperature, and melting temperature. The glass transition temperature can also be determined by dynamic mechanical analysis.

- Thermogravimetry is a useful technique to evaluate the thermal stability of the polymer.

- Rheology is used to characterize the flow and deformation behavior. It can be used to determine the viscosity, modulus, and other rheological properties. Rheology is also often used to determine the molecular architecture (molecular weight, molecular weight distribution, branching) and to understand how the polymer can be processed.

Degradation

A

plastic item with thirty years of exposure to heat and cold, brake

fluid, and sunlight. Notice the discoloration, swelling, and crazing of the material

Polymer degradation is a change in the properties—tensile strength, color,

shape, or molecular weight—of a polymer or polymer-based product under

the influence of one or more environmental factors, such as heat, light, chemicals and, in some cases, galvanic action. It is often due to the scission of polymer chain bonds via hydrolysis, leading to a decrease in the molecular mass of the polymer.

Although such changes are frequently undesirable, in some cases, such as biodegradation and recycling, they may be intended to prevent environmental pollution. Degradation can also be useful in biomedical settings. For example, a copolymer of polylactic acid and polyglycolic acid is employed in hydrolysable stitches that slowly degrade after they are applied to a wound.

The susceptibility of a polymer to degradation depends on its

structure. Epoxies and chains containing aromatic functionalities are

especially susceptible to UV degradation while polyesters are susceptible to degradation by hydrolysis, while polymers containing an unsaturated backbone are especially susceptible to ozone cracking. Carbon based polymers are more susceptible to thermal degradation than inorganic polymers such as polydimethylsiloxane and are therefore not ideal for most high-temperature applications. High-temperature matrices such as bismaleimides (BMI), condensation polyimides (with an O-C-N bond), triazines (with a nitrogen (N) containing ring), and blends thereof are susceptible to polymer degradation in the form of galvanic corrosion when bare carbon fiber reinforced polymer CFRP is in contact with an active metal such as aluminium in salt water environments.

The degradation of polymers to form smaller molecules may proceed

by random scission or specific scission. The degradation of

polyethylene occurs by random scission—a random breakage of the bonds

that hold the atoms

of the polymer together. When heated above 450 °C, polyethylene

degrades to form a mixture of hydrocarbons. Other polymers, such as

poly(alpha-methylstyrene), undergo specific chain scission with breakage

occurring only at the ends. They literally unzip or depolymerize back to the constituent monomer.

The sorting of polymer waste for recycling purposes may be facilitated by the use of the Resin identification codes developed by the Society of the Plastics Industry to identify the type of plastic.

Product failure

Chlorine attack of acetal resin plumbing joint

In a finished product, such a change is to be prevented or delayed. Failure of safety-critical polymer components can cause serious accidents, such as fire in the case of cracked and degraded polymer fuel lines. Chlorine-induced cracking of acetal resin plumbing joints and polybutylene pipes has caused many serious floods in domestic properties, especially in the US in the 1990s. Traces of chlorine

in the water supply attacked vulnerable polymers in the plastic

plumbing, a problem which occurs faster if any of the parts have been

poorly extruded or injection molded.

Attack of the acetal joint occurred because of faulty molding, leading

to cracking along the threads of the fitting which is a serious stress concentration.

Ozone-induced cracking in natural rubber tubing

Polymer oxidation has caused accidents involving medical devices. One of the oldest known failure modes is ozone cracking caused by chain scission when ozone gas attacks susceptible elastomers, such as natural rubber and nitrile rubber. They possess double bonds in their repeat units which are cleaved during ozonolysis.

Cracks in fuel lines can penetrate the bore of the tube and cause fuel

leakage. If cracking occurs in the engine compartment, electric sparks

can ignite the gasoline

and can cause a serious fire. In medical use degradation of polymers

can lead to changes of physical and chemical characteristics of

implantable devices.

Fuel lines can also be attacked by another form of degradation: hydrolysis. Nylon 6,6 is susceptible to acid hydrolysis, and in one accident, a fractured fuel line led to a spillage of diesel into the road. If diesel fuel leaks onto the road, accidents to following cars can be caused by the slippery nature of the deposit, which is like black ice. Furthermore, the asphalt concrete road surface will suffer damage as a result of the diesel fuel dissolving the asphaltenes from the composite material, this resulting in the degradation of the asphalt surface and structural integrity of the road.