"Burning ice". Methane, released by heating, burns; water drips.

Inset: clathrate structure (University of Göttingen, GZG. Abt. Kristallographie).

Source: United States Geological Survey.

Inset: clathrate structure (University of Göttingen, GZG. Abt. Kristallographie).

Source: United States Geological Survey.

Methane clathrates are common constituents of the shallow marine geosphere and they occur in deep sedimentary structures and form outcrops on the ocean floor. Methane hydrates are believed to form by the precipitation or crystallization of methane migrating from deep along geological faults. Precipitation occurs when the methane comes in contact with water within the sea bed subject to temperature and pressure. In 2008, research on Antarctic Vostok and EPICA Dome C ice cores revealed that methane clathrates were also present in deep Antarctic ice cores and record a history of atmospheric methane concentrations, dating to 800,000 years ago. The ice-core methane clathrate record is a primary source of data for global warming research, along with oxygen and carbon dioxide.

General

Methane

hydrates were discovered in Russia in the 1960s, and studies for

extracting gas from it emerged at the beginning of the 21st century.

Structure and composition

The nominal methane clathrate hydrate composition is (CH4)4(H2O)23, or 1 mole

of methane for every 5.75 moles of water, corresponding to 13.4%

methane by mass, although the actual composition is dependent on how

many methane molecules fit into the various cage structures of the water

lattice. The observed density is around 0.9 g/cm3,

which means that methane hydrate will float to the surface of the sea

or of a lake unless it is bound in place by being formed in or anchored

to sediment.

One liter of fully saturated methane clathrate solid would therefore

contain about 120 grams of methane (or around 169 liters of methane gas

at 0 °C and 1 atm), or one cubic metre of methane clathrate releases about 160 cubic metres of gas.

Methane forms a structure I hydrate with two dodecahedral (12 vertices, thus 12 water molecules) and six tetradecahedral

(14 water molecules) water cages per unit cell. (Because of sharing of

water molecules between cages, there are only 46 water molecules per

unit cell.) This compares with a hydration number of 20 for methane in aqueous solution. A methane clathrate MAS NMR spectrum recorded at 275 K and 3.1 MPa shows a peak for each cage type and a separate peak for gas phase methane.

In 2003, a clay-methane hydrate intercalate was synthesized in which a

methane hydrate complex was introduced at the interlayer of a

sodium-rich montmorillonite clay. The upper temperature stability of this phase is similar to that of structure I hydrate.

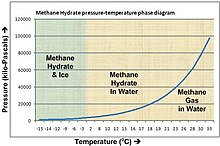

Methane

hydrate phase diagram. The horizontal axis shows temperature from -15

to 33 Celsius, the vertical axis shows pressure from 0 to 120,000

kilopascals (0 to 1,184 atmospheres). Hydrate forms above the line. For

example, at 4 Celsius hydrate forms above a pressure of about 50

atm/5000 kPa, found at about 500m sea depth.

Natural deposits

Worldwide distribution of confirmed or inferred offshore gas hydrate-bearing sediments, 1996. Source: USGS

Gas hydrate-bearing sediment, from the subduction zone off Oregon

Specific structure of a gas hydrate piece, from the subduction zone off Oregon

Methane clathrates are restricted to the shallow lithosphere (i.e. < 2,000 m depth). Furthermore, necessary conditions are found only in either continental sedimentary rocks in polar regions where average surface temperatures are less than 0 °C; or in oceanic sediment at water depths greater than 300 m where the bottom water temperature is around 2 °C. In addition, deep fresh water lakes may host gas hydrates as well, e.g. the fresh water Lake Baikal, Siberia. Continental deposits have been located in Siberia and Alaska in sandstone and siltstone beds at less than 800 m depth. Oceanic deposits seem to be widespread in the continental shelf (see Fig.) and can occur within the sediments at depth or close to the sediment-water interface. They may cap even larger deposits of gaseous methane.

Oceanic

There are two distinct types of oceanic deposit. The most common is dominated (> 99%) by methane contained in a structure I clathrate and generally found at depth in the sediment. Here, the methane is isotopically light (δ13C < −60‰), which indicates that it is derived from the microbial reduction of CO2. The clathrates in these deep deposits are thought to have formed in situ from the microbially produced methane, since the δ13C values of clathrate and surrounding dissolved methane are similar.

However, it is also thought that fresh water used in the

pressurization of oil and gas wells in permafrost and along the

continental shelves worldwide combines with natural methane to form

clathrate at depth and pressure, since methane hydrates are more stable

in fresh water than in salt water. Local variations may be very common,

since the act of forming hydrate, which extracts pure water from saline

formation waters, can often lead to local, and potentially significant,

increases in formation water salinity. Hydrates normally exclude the

salt in the pore fluid from which it forms, thus they exhibit high

electric resistivity just like ice, and sediments containing hydrates

have a higher resistivity compared to sediments without gas hydrates

(Judge [67]).

These deposits are located within a mid-depth zone around 300–500 m thick in the sediments (the gas hydrate stability zone,

or GHSZ) where they coexist with methane dissolved in the fresh, not

salt, pore-waters. Above this zone methane is only present in its

dissolved form at concentrations that decrease towards the sediment

surface. Below it, methane is gaseous. At Blake Ridge on the Atlantic continental rise, the GHSZ started at 190 m depth and continued to 450 m, where it reached equilibrium with the gaseous phase. Measurements indicated that methane occupied 0-9% by volume in the GHSZ, and ~12% in the gaseous zone.

In the less common second type found near the sediment surface some samples have a higher proportion of longer-chain hydrocarbons (< 99% methane) contained in a structure II clathrate. Carbon from this type of clathrate is isotopically heavier (δ13C

is −29 to −57 ‰) and is thought to have migrated upwards from deep

sediments, where methane was formed by thermal decomposition of organic matter. Examples of this type of deposit have been found in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caspian Sea.

Some deposits have characteristics intermediate between the

microbially and thermally sourced types and are considered to be formed

from a mixture of the two.

The methane in gas hydrates is dominantly generated by microbial

consortia degrading organic matter in low oxygen environments, with the

methane itself produced by methanogenic archaea. Organic matter in the uppermost few centimeters of sediments is first attacked by aerobic bacteria, generating CO2, which escapes from the sediments into the water column.

Below this region of aerobic activity, anaerobic processes take over,

including, successively with depth, the microbial reduction of

nitrite/nitrate, metal oxides, and then sulfates are reduced to sulfides. Finally, once sulfate is used up, methanogenesis becomes a dominant pathway for organic carbon remineralization.

If the sedimentation rate is low (about 1 cm/yr), the organic

carbon content is low (about 1% ), and oxygen is abundant, aerobic

bacteria can use up all the organic matter in the sediments faster than

oxygen is depleted, so lower-energy electron acceptors

are not used. But where sedimentation rates and the organic carbon

content are high, which is typically the case on continental shelves and

beneath western boundary current upwelling zones, the pore water in the sediments becomes anoxic

at depths of only a few centimeters or less. In such organic-rich

marine sediments, sulfate then becomes the most important terminal

electron acceptor due to its high concentration in seawater,

although it too is depleted by a depth of centimeters to meters. Below

this, methane is produced. This production of methane is a rather

complicated process, requiring a highly reducing environment (Eh −350 to

−450 mV) and a pH between 6 and 8, as well as a complex syntrophic consortia of different varieties of archaea and bacteria, although it is only archaea that actually emit methane.

In some regions (e.g., Gulf of Mexico) methane in clathrates may

be at least partially derived from thermal degradation of organic

matter, dominantly in petroleum. The methane in clathrates typically has a biogenic isotopic signature and highly variable δ13C (−40 to −100‰), with an approximate average of about −65‰ . Below the zone of solid clathrates, large volumes of methane may form bubbles of free gas in the sediments.

The presence of clathrates at a given site can often be

determined by observation of a "bottom simulating reflector" (BSR),

which is a seismic reflection at the sediment to clathrate stability

zone interface caused by the unequal densities of normal sediments and

those laced with clathrates.

Gas hydrate pingos,

have been discovered in the Arctic oceans Barents sea. Methane is

bubbling from these dome like structures, with some of these gas flares

extending close to the sea surface.

Reservoir size

The size of the oceanic methane clathrate reservoir is poorly known, and estimates of its size decreased by roughly an order of magnitude per decade since it was first recognized that clathrates could exist in the oceans during the 1960s and 1970s. The highest estimates (e.g. 3×1018 m3)

were based on the assumption that fully dense clathrates could litter

the entire floor of the deep ocean. Improvements in our understanding of

clathrate chemistry and sedimentology have revealed that hydrates form

in only a narrow range of depths (continental shelves), at only some locations in the range of depths where they could occur (10-30% of the Gas hydrate stability zone),

and typically are found at low concentrations (0.9–1.5% by volume) at

sites where they do occur. Recent estimates constrained by direct

sampling suggest the global inventory occupies between 1×1015and 5×1015 m3 (0.24 to 1.2 million cubic miles).

This estimate, corresponding to 500–2500 gigatonnes carbon (Gt C), is

smaller than the 5000 Gt C estimated for all other geo-organic fuel

reserves but substantially larger than the ~230 Gt C estimated for other

natural gas sources. The permafrost reservoir has been estimated at about 400 Gt C in the Arctic,

but no estimates have been made of possible Antarctic reservoirs. These

are large amounts. In comparison, the total carbon in the atmosphere is

around 800 gigatons.

These modern estimates are notably smaller than the 10,000 to 11,000 Gt C (2×1016 m3) proposed

by previous researchers as a reason to consider clathrates to be a

geo-organic fuel resource (MacDonald 1990, Kvenvolden 1998). Lower

abundances of clathrates do not rule out their economic potential, but a

lower total volume and apparently low concentration at most sites does suggest that only a limited percentage of clathrates deposits may provide an economically viable resource.

Continental

Methane clathrates in continental rocks are trapped in beds of sandstone or siltstone

at depths of less than 800 m. Sampling indicates they are formed from a

mix of thermally and microbially derived gas from which the heavier

hydrocarbons were later selectively removed. These occur in Alaska, Siberia, and Northern Canada.

In 2008, Canadian and Japanese researchers extracted a constant stream of natural gas from a test project at the Mallik gas hydrate site in the Mackenzie River

delta. This was the second such drilling at Mallik: the first took

place in 2002 and used heat to release methane. In the 2008 experiment,

researchers were able to extract gas by lowering the pressure, without

heating, requiring significantly less energy. The Mallik gas hydrate field was first discovered by Imperial Oil in 1971-1972.

Commercial use

Economic deposits of hydrate are termed Natural Gas Hydrate (NGH) and are unique in that they store 164 m3 of methane, 0.8 m3 water in 1 m3 hydrate.

Most NGH is found beneath the seafloor (95%) where it exists in

thermodynamic equilibrium. The sedimentary methane hydrate reservoir

probably contains 2–10 times the currently known reserves of

conventional natural gas, as of 2013. This represents a potentially important future source of hydrocarbon fuel. However, in the majority of sites deposits are thought to be too dispersed for economic extraction.

Other problems facing commercial exploitation are detection of viable

reserves and development of the technology for extracting methane gas

from the hydrate deposits.

In August 2006, China announced plans to spend 800 million yuan

(US$100 million) over the next 10 years to study natural gas hydrates. A potentially economic reserve in the Gulf of Mexico may contain approximately 100 billion cubic metres (3.5×1012 cu ft) of gas. Bjørn Kvamme and Arne Graue at the Institute for Physics and technology at the University of Bergen have developed a method for injecting CO2 into hydrates and reversing the process; thereby extracting CH4 by direct exchange. The University of Bergen's method is being field tested by ConocoPhillips and state-owned Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation

(JOGMEC), and partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. The

project has already reached injection phase and was analyzing resulting

data by March 12, 2012.

On March 12, 2013, JOGMEC researchers announced that they had successfully extracted natural gas from frozen methane hydrate.

In order to extract the gas, specialized equipment was used to drill

into and depressurize the hydrate deposits, causing the methane to

separate from the ice. The gas was then collected and piped to surface

where it was ignited to prove its presence. According to an industry spokesperson, "It [was] the world's first offshore experiment producing gas from methane hydrate". Previously, gas had been extracted from onshore deposits, but never from offshore deposits which are much more common. The hydrate field from which the gas was extracted is located 50 kilometres (31 mi) from central Japan in the Nankai Trough, 300 meters (980 ft) under the sea. A spokesperson for JOGMEC remarked "Japan could finally have an energy source to call its own". The experiment will continue for two weeks before it is determined how efficient the gas extraction process has been.

Marine geologist Mikio Satoh remarked "Now we know that extraction is

possible. The next step is to see how far Japan can get costs down to

make the technology economically viable."

Japan estimates that there are at least 1.1 trillion cubic meters of

methane trapped in the Nankai Trough, enough to meet the country's needs

for more than ten years.

Both Japan and China announced in May 2017 a breakthrough for mining methane clathrates, when they extracted methane from hydrates in the South China Sea. However, industry consensus is that commercial-scale production remains years away.

Environmental concerns

Experts

caution that environmental impacts are still being investigated and

that methane—a greenhouse gas with around 25 times as much global warming potential

over a 100-year period (GWP100) as carbon dioxide—could potentially

escape into the atmosphere if something goes wrong. Furthermore, while

cleaner than coal, burning natural gas also creates carbon emissions.

Hydrates in natural gas processing

Routine operations

Methane

clathrates (hydrates) are also commonly formed during natural gas

production operations, when liquid water is condensed in the presence of

methane at high pressure. It is known that larger hydrocarbon molecules

like ethane and propane can also form hydrates, although longer

molecules (butanes, pentanes) cannot fit into the water cage structure

and tend to destabilize the formation of hydrates.

Once formed, hydrates can block pipeline and processing

equipment. They are generally then removed by reducing the pressure,

heating them, or dissolving them by chemical means (methanol is commonly

used). Care must be taken to ensure that the removal of the hydrates is

carefully controlled, because of the potential for the hydrate to

undergo a phase transition from the solid hydrate to release water and

gaseous methane at a high rate when the pressure is reduced. The rapid

release of methane gas in a closed system can result in a rapid increase

in pressure.

It is generally preferable to prevent hydrates from forming or

blocking equipment. This is commonly achieved by removing water, or by

the addition of ethylene glycol (MEG) or methanol, which act to depress the temperature at which hydrates will form (i.e. common antifreeze).

In recent years, development of other forms of hydrate inhibitors have

been developed, like Kinetic Hydrate Inhibitors (which by far slow the

rate of hydrate formation) and anti-agglomerates, which do not prevent

hydrates forming, but do prevent them sticking together to block

equipment.

Effect of hydrate phase transition during deep water drilling

When

drilling in oil- and gas-bearing formations submerged in deep water,

the reservoir gas may flow into the well bore and form gas hydrates

owing to the low temperatures and high pressures found during deep water

drilling. The gas hydrates may then flow upward with drilling mud or

other discharged fluids. When the hydrates rise, the pressure in the annulus

decreases and the hydrates dissociate into gas and water. The rapid gas

expansion ejects fluid from the well, reducing the pressure further,

which leads to more hydrate dissociation and further fluid ejection. The

resulting violent expulsion of fluid from the annulus is one potential

cause or contributor to the "kick". (Kicks, which can cause blowouts, typically do not involve hydrates).

Measures which reduce the risk of hydrate formation include:

- High flow-rates, which limit the time for hydrate formation in a volume of fluid, thereby reducing the kick potential.

- Careful measuring of line flow to detect incipient hydrate plugging.

- Additional care in measuring when gas production rates are low and the possibility of hydrate formation is higher than at relatively high gas flow rates.

- Monitoring of well casing after it is "shut in" (isolated) may indicate hydrate formation. Following "shut in", the pressure rises while gas diffuses through the reservoir to the bore hole; the rate of pressure rise exhibit a reduced rate of increase while hydrates are forming.

- Additions of energy (e.g., the energy released by setting cement used in well completion) can raise the temperature and convert hydrates to gas, producing a "kick".

Blowout recovery

Concept

diagram of oil containment domes, forming upsidedown funnels in order

to pipe oil to surface ships. The sunken oil rig is nearby.

At sufficient depths, methane complexes directly with water to form methane hydrates, as was observed during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. BP engineers developed and deployed a subsea oil recovery system over oil spilling from a deepwater oil well 5,000 feet (1,500 m) below sea level

to capture escaping oil. This involved placing a 125-tonne (276,000 lb)

dome over the largest of the well leaks and piping it to a storage

vessel on the surface. This option had the potential to collect some 85% of the leaking oil but was previously untested at such depths.

BP deployed the system on May 7–8, but it failed due to buildup of

methane clathrate inside the dome; with its low density of approximately

0.9 g/cm3 the methane hydrates accumulated in the dome, adding buoyancy and obstructing flow.

Methane clathrates and climate change

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. Despite its short atmospheric half life of 12 years, methane has a global warming potential

of 86 over 20 years and 34 over 100 years (IPCC, 2013). The sudden

release of large amounts of natural gas from methane clathrate deposits

has been hypothesized as a cause of past and possibly future climate changes. Events possibly linked in this way are the Permian-Triassic extinction event and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.

Climate scientists like James E. Hansen predict that methane clathrates in permafrost regions will be released because of global warming, unleashing powerful feedback forces that may cause runaway climate change.

Research carried out in 2008 in the Siberian Arctic found millions of tonnes of methane being released with concentrations in some regions reaching up to 100 times above normal.

In their Correspondence in the September 2013 Nature Geoscience

journal, Vonk and Gustafsson cautioned that the most probable mechanism

to strengthen global warming is large-scale thawing of Arctic

permafrost which will release methane clathrate into the atmosphere.

While performing research in July in plumes in the East Siberian Arctic

Ocean, Gustafsson and Vonk were surprised by the high concentration of

methane.

In 2014 based on their research on the northern United States Atlantic marine continental margins from Cape Hatteras to Georges Bank,

a group of scientists from the US Geological Survey, the Department of

Geosciences, Mississippi State University, Department of Geological

Sciences, Brown University and Earth Resources Technology, claimed there

was widespread leakage of methane.

Scientists from the Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate (CAGE), Environment and Climate at the Arctic University of Norway,

published a study in June 2017, describing over a hundred ocean

sediment craters, some 3,000 meters wide and up to 300 meters deep,

formed due to explosive eruptions, attributed to destabilizing methane

hydrates, following ice-sheet retreat during the last glacial period, around 12,000 years ago, a few centuries after the Bølling-Allerød warming. These areas around the Barents Sea, still seep methane today, and still existing bulges with methane reservoirs could eventually have the same fate.

Natural gas hydrates versus liquified natural gas in transportation

Since methane clathrates are stable at a higher temperature than liquefied natural gas (LNG)

(−20 vs −162 °C), there is some interest in converting natural gas into

clathrates rather than liquifying it when transporting it by seagoing vessels. A significant advantage would be that the production of natural gas hydrate (NGH)

from natural gas at the terminal would require a smaller refrigeration

plant and less energy than LNG would. Offsetting this, for 100 tonnes of

methane transported, 750 tonnes of methane hydrate would have to be

transported; since this would require a ship of 7.5 times greater

displacement, or require more ships, it is unlikely to prove

economically feasible.