Intersex, in humans and other animals, describes variations in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies". Intersex people were historically termed hermaphrodites, "congenital eunuchs", or even congenitally "frigid". Such terms have fallen out of favor, now considered to be misleading and stigmatizing.

Intersex people have been treated in different ways by different cultures. Whether or not they were socially tolerated or accepted by any particular culture, the existence of intersex people was known to many ancient and pre-modern cultures and legal systems, and numerous historical accounts exist.

Intersex people have been treated in different ways by different cultures. Whether or not they were socially tolerated or accepted by any particular culture, the existence of intersex people was known to many ancient and pre-modern cultures and legal systems, and numerous historical accounts exist.

Ancient history

Sumer

A Sumerian creation myth from more than 4,000 years ago has Ninmah, a mother goddess, fashioning humanity out of clay. She boasts that she will determine the fate – good or bad – for all she fashions:

Enki answered Ninmah: "I will counterbalance whatever fate – good or bad – you happen to decide.

Ninmah took clay from the top of the abzu [ab: water; zu: far] in her hand and she fashioned from it first a man who could not bend his outstretched weak hands. Enki looked at the man who cannot bend his outstretched weak hands, and decreed his fate: he appointed him as a servant of the king. (Three men and one woman with atypical biology are formed and Enki gives each of them various forms of status to ensure respect for their uniqueness)

...Sixth, she fashioned one with neither penis nor vagina on its body. Enki looked at the one with neither penis nor vagina on its body and gave it the name Nibru (eunuch(?)), and decreed as its fate to stand before the king.

Ancient Judaism

In traditional Jewish culture, intersex individuals were either androgynos or tumtum and took on different gender roles, sometimes conforming to men's, sometimes to women's.

Ancient Islam

By the eighth century CE, records of Islamic legal rulings discuss individuals known in Arabic as khuntha.

This term, which has been translated as "hermaphrodite," was used to

apply to individuals with a range of intersex conditions, including mixed gonadal disgenesis, male hypospadias, partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, 5-alpha reductase deficiency, gonadal aplasia, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

In Islamic law, inheritance

was determined based on sex, so it was sometimes necessary to attempt

to determine the biological sex of sexually ambiguous heirs. The first recorded case of this sort has been attributed to the seventh-century Rashidun caliph named 'Ali, who attempted to settle an inheritance case between five brothers in which one brother had both a male and female urinary opening. 'Ali advised the brothers that sex could be determined by site of urination in a practice called hukm al-mabal;

if urine exited the male opening, the individual was male, and if it

exited the female opening, the individual was female. If it exited both

openings simultaneously, as it did in this case, the heir would be given

half of a male inheritance and half of a female inheritance. Later, in the thirteenth century CE, Shafi'i law expert Abu Zakariya al-Nawawi ruled that an individual whose sex could not be determined by hukm al-mabal,

such as those with urination from both openings or those with no

identifiable sex organs, was assigned the intermediary sex category khuntha mushkil.

Both Hanafi and Hanbali lawmakers also recognized that puberty could clarify a new dominant sex in intersex individuals who were labeled khuntha, male, or female in childhood. If a khuntha

or male developed female secondary sex characteristics, performed

vaginal sex, lactacted, menstruated, or conceived, this person's legal

sex could change to female. Conversely, if a khuntha or female

developed male secondary sex characteristics, performed penetrative sex

with a woman, or had an erection, their legal sex could change to male.

This understanding of the effect of puberty on intersex conditions

appears in Islamic law as early as the eleventh century CE, notably by Ibn Qudama.

In the sixteenth century CE, Ibrahim al-Halabi, a member of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence

in Islam, directed slave owners to use special gender-neutral language

when freeing intersex slaves. He recognized that language manumitting

"males" or "females" would not directly apply to them.

Ancient South Asia

Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous composite form of male deity Shiva and female deity Parvati, originated in Kushan culture as far back as the first century CE. A statue depicting Ardhanarishvara is included in India's Meenkashi Temple; this statue clearly shows both male and female bodily elements.

Due to the presence of intersex traits, Ardhanarishvara is associated with the hijra, a third sex category that has been accepted in South Asia for centuries. After interviewing and studying the hijra for many years, Serena Nanda writes in her book Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India as follows: "There is a widespread belief in India that hijras are born hermaphrodites [intersex] and are taken away by the hijra community at birth or in childhood, but I found no evidence to support this belief among the hijras I met, all of whom joined the community voluntarily, often in their teens."

According to Gilbert Herdt, the hijra differentiate between "born" and "made" individuals, or those who have physical intersex traits by birth and those who become hijra through penectomy, respectively. According to Indian tradition, the hijra

perform a traditional song and dance as part of a family's celebration

of the birth of a male child; during the performance, they also inspect

the newborn's genitals to verify its sex. Herdt states that it is widely

accepted that if the child is intersex, the hijra have a right to claim it as part of their community.

However, Warne and Raza argue that an association between intersex and

hijra people is mostly unfounded but provokes parental fear. The hijra are mentioned in some versions of the Ramayana, a Hindu epic poem from around 300 BCE, in a myth about the hero Rama instructing his devotees to return to the city Ayodhya

rather than follow him across the city's adjacent river into

banishment. Since he gives this instruction specifically to "all you men

and women," his hijra followers, being neither, remain on the banks of the river for fourteen years until Rama returns from exile.

In the Tantric

sect of Hinduism, there is a belief that all individuals possess both

male and female components. This belief can be seen explicitly in the

Tantric concept of a Supreme Being with both male and female sex organs, which constitutes "one complete sex" and the ideal physical form.

Ancient Greece

According to Leah DeVun, a "traditional Hippocratic/Galenic model of sexual difference – popularized by the late antique physician Galen

and the ascendant theory for much of the Middle Ages – viewed sex as a

spectrum that encompassed masculine men, feminine women, and many shades

in between, including hermaphrodites, a perfect balance of male and

female".

DeVun contrasts this with an Artistotelian view of intersex, which

argued that "hermaphrodites were not an intermediate sex but a case of

doubled or superfluous genitals", and this later influenced Aquinas.

In the mythological tradition, Hermaphroditus was a beautiful youth who was the son of Hermes (Roman Mercury) and Aphrodite (Venus). Ovid wrote the most influential narrative of how Hermaphroditus became androgynous, emphasizing that although the handsome youth was on the cusp of sexual adulthood, he rejected love as Narcissus had, and likewise at the site of a reflective pool. There the water nymph Salmacis

saw and desired him. He spurned her, and she pretended to withdraw

until, thinking himself alone, he undressed to bathe in her waters. She

then flung herself upon him, and prayed that they might never be parted.

The gods granted this request, and thereafter the body of

Hermaphroditus contained both male and female. As a result, men who

drank from the waters of the spring Salmacis supposedly "grew soft with

the vice of impudicitia". The myth of Hylas, the young companion of Hercules who was abducted by water nymphs,

shares with Hermaphroditus and Narcissus the theme of the dangers that

face the beautiful adolescent male as he transitions to adult

masculinity, with varying outcomes for each.

Ancient Rome

Hermaphroditus in a wall painting from Herculaneum (first half of the 1st century AD)

Pliny notes that "there are even those who are born of both sexes, whom we call hermaphrodites, at one time androgyni" (andr-, "man," and gyn-, "woman", from the Greek). However, the era also saw a historical account of a congenital eunuch.

The Sicilian historian Diodorus (latter 1st-century BC) wrote of "hermaphroditus" in the first century BCE:

Hermaphroditus, as he has been called, who was born of Hermes and Aphrodite and received a name which is a combination of those of both his parents. Some say that this Hermaphroditus is a god and appears at certain times among men, and that he is born with a physical body which is a combination of that of a man and that of a woman, in that he has a body which is beautiful and delicate like that of a woman, but has the masculine quality and vigour of man. But there are some who declare that such creatures of two sexes are monstrosities, and coming rarely into the world as they do they have the quality of presaging the future, sometimes for evil and sometimes for good.

Isidore of Seville (c.

560–636) described a hermaphrodite fancifully as those who "have the

right breast of a man and the left of a woman, and after coitus in turn

can both sire and bear children." Under Roman law, as many others, a hermaphrodite had to be classed as either male or female. Will Roscoe

writes that the hermaphrodite represented a "violation of social

boundaries, especially those as fundamental to daily life as male and

female."

In traditional Roman religion, a hermaphroditic birth was a kind of prodigium, an occurrence that signalled a disturbance of the pax deorum, Rome's treaty with the gods. But Pliny observed that while hermaphrodites were once considered portents, in his day they had become objects of delight (deliciae) who were trafficked in an exclusive slave market.[31] According to historian John Clarke, depictions of Hermaphroditus were very popular among the Romans:

Artistic representations of Hermaphroditus bring to the fore the ambiguities in sexual differences between women and men as well as the ambiguities in all sexual acts. ... (A)rtists always treat Hermaphroditus in terms of the viewer finding out his/her actual sexual identity. ... Hermaphroditus is a highly sophisticated representation, invading the boundaries between the sexes that seem so clear in classical thought and representation.[32]

In c.400, Augustine wrote in The Literal Meaning of Genesis that humans were created in two sexes, despite "as happens in some births, in the case of what we call androgynes".

Historical accounts of intersex people include the sophist and philosopher Favorinus, described as a eunuch (εὐνοῦχος) by birth. Mason and others thus describe Favorinus as having an intersex trait.

A broad sense of the term "eunuch" is reflected in the compendium of ancient Roman laws collected by Justinian I in the 6th century known as the Digest or Pandects. Those texts distinguish between the general category of eunuchs (spadones, denoting "one who has no generative power, an impotent person, whether by nature or by castration", D 50.16.128) and the more specific subset of castrati (castrated males, physically incapable of procreation). Eunuchs (spadones) sold in the slave markets were deemed by the jurist Ulpian to be "not defective or diseased, but healthy", because they were anatomically able to procreate just like monorchids (D 21.1.6.2). On the other hand, as Julius Paulus

pointed out, "if someone is a eunuch in such a way that he is missing a

necessary part of his body" (D 21.1.7), then he would be deemed

diseased. In these Roman legal texts, spadones (eunuchs) are

eligible to marry women (D 23.3.39.1), institute posthumous heirs (D

28.2.6), and adopt children (Institutions of Justinian 1.11.9), unless they are castrati.

Middle Ages

An illustration from a 13th-century manuscript of the Decretum Gratiani

In Abnormal (Les anormaux), Michel Foucault

suggested it is likely that, "from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth

century ... hermaphrodites were considered to be monsters and were

executed, burnt at the stake and their ashes thrown to the winds."

However, Christof Rolker disputes this, arguing that "Contrary to

what has been claimed, there is no evidence for hermaphrodites being

persecuted in the Middle Ages, and the learned laws did certainly not

provide any basis for such persecution". Canon Law

sources provide evidence of alternative perspectives, based upon

prevailing visual indications and the performance of gendered roles. The 12th-century Decretum Gratiani

states that "Whether an hermaphrodite may witness a testament, depends

on which sex prevails" ("Hermafroditus an ad testamentum adhiberi

possit, qualitas sexus incalescentis ostendit.").

In the late twelfth century, the canon lawyer Huguccio

stated that, "If someone has a beard, and always wishes to act like a

man (excercere virilia) and not like a female, and always wishes to keep

company with men and not with women, it is a sign that the male sex

prevails in him and then he is able to be a witness, where a woman is

not allowed".

Concerning the ordination of 'hermaphrodites', Huguccio concluded: "If

therefore the person is drawn to the feminine more than the male, the

person does not receive the order. If the reverse, the person is able to

receive but ought not to be ordained on account of deformity and

monstrosity."

Henry de Bracton's De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae ("On the Laws and Customs of England"), c. 1235, classifies mankind as "male, female, or hermaphrodite", and "A hermaphrodite is classed with male or female according to the predominance of the sexual organs."

The thirteenth-century canon lawyer Henry of Segusio argued that a "perfect hermaphrodite" where no sex prevailed should choose their legal gender under oath.

Early modern period

The 17th-century English jurist and judge Edward Coke (Lord Coke), wrote in his Institutes of the Lawes of England

on laws of succession stating, "Every heire is either a male, a female,

or an hermaphrodite, that is both male and female. And an hermaphrodite

(which is also called Androgynus) shall be heire, either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile." The Institutes are widely held to be a foundation of common law.

A few historical accounts of intersex people exist due primarily to the discovery of relevant legal records, including those of Thomas(ine) Hall (17th-century United States), Eleno de Céspedes, a 16th-century intersex person in Spain (in Spanish), and Fernanda Fernández (18th-century Spain).

In 2019 the Smithsonian Channel aired a documentary "American's Hidden Stories: The General was Female?" with evidence that Casimir Pulaski, the important American Revolutionary War hero, may have been intersex.

In a court case, heard at the Castellania in 1774 during the Order of St. John in Malta, 17-year-old Rosa Mifsud from Luqa, later described in the British Medical Journal as a pseudo-hermaphrodite, petitioned for a change in sex classification from female. Two clinicians were appointed by the court to perform an examination. They found that "the male sex is the dominant one". The examiners were the Physician-in-Chief and a senior surgeon, both working at the Sacra Infermeria. The Grandmaster himself who took the final decision for Mifsud to wear only men clothes from then on.

Maria Dorothea Derrier/Karl Dürrge was a German intersex person who made their living for 30 years as a human research subject.

Born in Potsdam in 1780, and designated as female at birth, they

assumed a male identity around 1807. Traveling intersex persons, like

Derrier and Katharina/Karl Hohmann, who allowed themselves to be examined by physicians were instrumental in the development of codified standards for sexing.

Mid modern period

Bronze statue of Lê Văn Duyệt in his tomb

During the Victorian era,

medical authors introduced the terms "true hermaphrodite" for an

individual who has both ovarian and testicular tissue, verified under a

microscope, "male pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with testicular

tissue, but either female or ambiguous sexual anatomy, and "female

pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with ovarian tissue, but either male

or ambiguous sexual anatomy.

Historical accounts including those of Vietnamese general Lê Văn Duyệt (18th/19th-century) who helped to unify Vietnam; Gottlieb Göttlich, a 19th-century German travelling medical case; and Levi Suydam, an intersex person in 19th-century USA whose capacity to vote in male-only elections was questioned.

The memoirs of 19th-century intersex Frenchwoman Herculine Barbin were published by Michel Foucault in 1980. Her birthday is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance on 8 November.

Contemporary period

The Phall-O-Meter satirizes clinical assessments of appropriate clitoris and penis length at birth.

The term intersexuality was coined by Richard Goldschmidt in the 1917 paper Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex. The first suggestion to replace the term 'hermaphrodite' with 'intersex' came from British specialist Cawadias in the 1940s. This suggestion was taken up by specialists in the UK during the 1960s.

Historical accounts from the early twentieth century include that of

Australian Florrie Cox, whose marriage was annulled due to "malformation

frigidity".

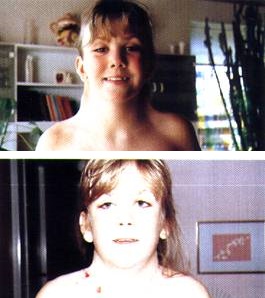

Since the rise of modern medical science in Western societies,

some intersex people with ambiguous external genitalia have had their

genitalia surgically modified to resemble either female or male

genitals. Surgeons pinpointed intersex babies as a "social emergency"

once they were born.

The parents of the intersex babies were not content about the

situation. Psychologists, sexologists, and researchers frequently still

believe that it is better for a baby's genitalia to be changed when they

were younger than when they were a mature adult. These scientists

believe that early intervention helped avoid gender identity confusion. This was called the 'Optimal Gender Policy', and it was initially developed in the 1950s by John Money. Money and others controversially

believed that children were more likely to develop a gender identity

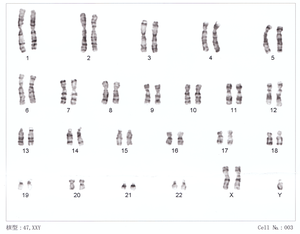

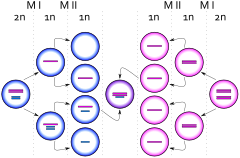

that matched sex of rearing than might be determined by chromosomes,

gonads, or hormones.

The primary goal of assignment was to choose the sex that would lead to

the least inconsistency between external anatomy and assigned psyche

(gender identity).

Since advances in surgery have made it possible for intersex

conditions to be concealed, many people are not aware of how frequently

intersex conditions arise in human beings or that they occur at all.

Dialog between what were once antagonistic groups of activists and

clinicians has led to only slight changes in medical policies and how

intersex patients and their families are treated in some locations.

Numerous civil society organizations and human rights institutions now

call for an end to unnecessary "normalizing" interventions.

The first public demonstration by intersex people took place in

Boston on October 26, 1996, outside the venue in Boston where the American Academy of Pediatrics was holding its annual conference. The group demonstrated against "normalizing" treatments, and carried a sign saying "Hermaphrodites With Attitude". The event is now commemorated by Intersex Awareness Day.

In 2011, Christiane Völling

became the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for

damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention. In April 2015, Malta

became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions

to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.