| Klinefelter syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | XXY syndrome, Klinefelter's syndrome, Klinefelter-Reifenstein-Albright syndrome |

| |

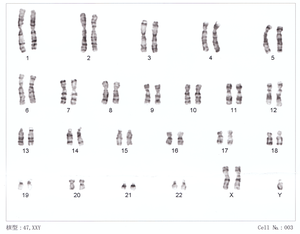

| 47,XXY karyotype | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Often few |

| Usual onset | At fertilisation |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Two or more X chromosomes in males |

| Risk factors | Older mother |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing (karyotype) |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, speech and language therapy, counseling |

| Prognosis | Nearly normal life expectancy |

| Frequency | 1:500 to 1:1,000 males |

Klinefelter syndrome (KS), also known as 47, XXY is the set of symptoms that result from two or more X chromosomes in males. The primary features are infertility and small poorly functioning testicles. Often, symptoms may be subtle and many people do not realize they are affected. Sometimes, symptoms are more prominent and may include weaker muscles, greater height, poor coordination, less body hair, breast growth, and less interest in sex. Often it is only at puberty that these symptoms are noticed. Intelligence is usually normal; however, reading difficulties and problems with speech are more common. Symptoms are typically more severe if three or more X chromosomes are present (48,XXXY syndrome or 49,XXXXY syndrome).

Klinefelter syndrome occurs randomly. The extra X chromosome comes from the father and mother nearly equally. An older mother may have a slightly increased risk of a child with KS. The condition is not typically inherited from one's parents. The underlying mechanisms involves at least one extra X chromosome in addition to a Y chromosome such that the total chromosome number is 47 or more rather than the usual 46. KS is diagnosed by the genetic test known as a karyotype.

While no cure is known, a number of treatments may help. Physical therapy, speech and language therapy, counselling, and adjustments of teaching methods may be useful. Testosterone replacement may be used in those who have significantly lower levels. Enlarged breasts may be removed by surgery. About half of affected males have a chance of fathering children with the help of assisted reproductive technology, but this is expensive and not risk free. XXY males appear to have a higher risk of breast cancer than typical, but still lower than that of females. People with the condition have a nearly normal life expectancy.

Klinefelter syndrome is one of the most common chromosomal disorders, occurring in one to two per 1,000 live male births. It is named after American endocrinologist Harry Klinefelter, who identified the condition in the 1940s. In 1956, identification of the extra X chromosome was first noticed. Mice can also have the XXY syndrome, making them a useful research model.

Signs and symptoms

The primary features are infertility and small poorly functioning testicles. Often, symptoms may be subtle and many people do not realize they are affected. Sometimes, symptoms are more prominent and may include weaker muscles, greater height, poor coordination, less body hair, breast growth, and less interest in sex. Often it is only at puberty that these symptoms are noticed.

Physical

As

babies and children, XXY males may have weaker muscles and reduced

strength. As they grow older, they tend to become taller than average.

They may have less muscle control and coordination than other boys of

their age.

During puberty, the physical traits of the syndrome become more

evident; because these boys do not produce as much testosterone as other

boys, they have a less muscular body, less facial and body hair, and

broader hips. As teens, XXY males may develop breast tissue and also have weaker bones, and a lower energy level than other males.

By adulthood, XXY males look similar to males without the

condition, although they are often taller. In adults, possible

characteristics vary widely and include little to no sign of

affectedness, a lanky, youthful build and facial appearance, or a rounded body type with some degree of gynecomastia (increased breast tissue).

Gynecomastia is present to some extent in about a third of affected

individuals, a slightly higher percentage than in the XY population.

About 10% of XXY males have gynecomastia noticeable enough that they may

choose to have cosmetic surgery.

Affected males are often infertile, or may have reduced fertility. Advanced reproductive assistance is sometimes possible.

The term hypogonadism

in XXY symptoms is often misinterpreted to mean "small testicles" when

it means decreased testicular hormone/endocrine function. Because of

this (primary) hypogonadism, individuals often have a low serum testosterone level, but high serum follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels. Despite this misunderstanding of the term, however, XXY men may also have microorchidism (i.e., small testicles).

The testicle size of affected males are usually less than 2 cm in length (and always shorter than 3.5 cm), 1 cm in width, and 4 ml in volume.

XXY males are also more likely than other men to have certain health problems, such as autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, venous thromboembolic disease, and osteoporosis. In contrast to these potentially increased risks, rare X-linked recessive

conditions are thought to occur less frequently in XXY males than in

normal XY males, since these conditions are transmitted by genes on the X

chromosome, and people with two X chromosomes are typically only carriers rather than affected by these X-linked recessive conditions.

Cognitive and developmental

Some degree of language learning or reading impairment may be present, and neuropsychological testing often reveals deficits in executive functions, although these deficits can often be overcome through early intervention. Also, delays in motor development may occur, which can be addressed through occupational and physical therapies.

XXY males may sit up, crawl, and walk later than other infants; they

may also struggle in school, both academically and with sports.

Endocrine

Men

with Klinefelter's syndrome have testosterone levels that are

significantly lower (−260 ng/dL difference), estradiol levels that are

slightly higher (+6.8 pg/mL) though not significantly different when

restricted to high-accuracy assays (+5.5 pg/mL difference), and the

ratio of estradiol to testosterone is significantly higher (+0.06).

Cause

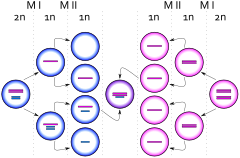

Birth of a cell with karyotype XXY due to a nondisjunction event of one X chromosome from a Y chromosome during meiosis I in the male

Birth of a cell with karyotype XXY due to a nondisjunction event of one X chromosome during meiosis II in the female

Maternal age is the only known risk factor. Women at 40 years have a four times higher risk for a child with Klinefelter syndrome than women aged 24 years.

The extra chromosome is retained because of a nondisjunction event during paternal meiosis I, maternal meiosis I, or maternal meiosis II

(gametogenesis). The relevant nondisjunction in meiosis I occurs when

homologous chromosomes, in this case the X and Y or two X sex

chromosomes, fail to separate, producing a sperm with an X and a Y

chromosome or an egg with two X chromosomes. Fertilizing a normal (X)

egg with this sperm produces an XXY offspring (Klinefelter). Fertilizing

a double X egg with a normal sperm also produces an XXY offspring

(Klinefelter).

Another mechanism for retaining the extra chromosome is through a nondisjunction event during meiosis II

in the egg. Nondisjunction occurs when sister chromatids on the sex

chromosome, in this case an X and an X, fail to separate. An XX egg is

produced, which when fertilized with a Y sperm, yields an XXY offspring.

This XXY chromosome arrangement is one of the most common genetic

variations from the XY karyotype, occurring in about one in 500 live

male births.

In mammals with more than one X chromosome, the genes on all but one X chromosome are not expressed; this is known as X inactivation. This happens in XXY males, as well as normal XX females. However, in XXY males, a few genes located in the pseudoautosomal regions of their X chromosomes have corresponding genes on their Y chromosome and are capable of being expressed.

Variations

48,XXYY or 48,XXXY occurs in one in 18,000–50,000 male births. The incidence of 49,XXXXY is one in 85,000 to 100,000 male births.

These variations are extremely rare. Additional chromosomal material

can contribute to cardiac, neurological, orthopedic, and other

anomalies.

Males with KS may have a mosaic

47,XXY/46,XY constitutional karyotype and varying degrees of

spermatogenic failure. Mosaicism 47,XXY/46,XX with clinical features

suggestive of KS is very rare. Thus far, only about 10 cases have been

described in literature.

Analogous XXY syndromes are known to occur in cats—specifically, the presence of calico or tortoiseshell

markings in male cats is an indicator of the relevant abnormal

karyotype. As such, male cats with calico or tortoiseshell markings are a

model organism for KS, because a color gene involved in cat tabby coloration is on the X chromosome.

Diagnosis

The standard diagnostic method is the analysis of the chromosomes' karyotype on lymphocytes. A small blood sample is sufficient as test material. In the past, the observation of the Barr body was common practice, as well. To investigate the presence of a possible mosaicism,

analysis of the karyotype using cells from the oral mucosa is

performed. Physical characteristics of a Klinefelter syndrome can be

tall stature, low body hair and occasionally an enlargement of the

breast. There is usually a small testicle volume of 1–5 ml per testicle

(standard values: 12–30 ml).

During puberty and adulthood, low testosterone levels with increased

levels of the pituitary hormones FSH and LH in the blood can indicate

the presence of Klinefelter syndrome. A spermiogram can also be part of

the further investigation. Often there is an azoospermia present, rarely

an oligospermia.

Furthermore, Klinefelter syndrome can be diagnosed as a coincidental

prenatal finding in the context of invasive prenatal diagnosis

(amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling). About 10% of KS cases are

found by prenatal diagnosis.

The symptoms of KS are often variable; therefore, a karyotype

analysis should be ordered when small testes, infertility, gynecomastia,

long arms/legs, developmental delay, speech/language deficits, learning

disabilities/academic issues, and/or behavioral issues are present in

an individual.

Treatment

The

genetic variation is irreversible, thus there is no causal therapy.

From the onset of puberty, the existing testosterone deficiency can be

compensated by appropriate hormone replacement therapy. Testosterone preparations are available in the form of syringes, patches or gel. If gynecomastia is present, the surgical removal of the breast may be considered for both the psychological reasons and to reduce the risk of breast cancer.

The use of behavioral therapy can mitigate any language disorders, difficulties at school, and socialization. An approach by occupational therapy is useful in children, especially those who have dyspraxia.

Infertility treatment

Methods of reproductive medicine, such as intracytoplasmic sperm

injection (ICSI) with previously conducted testicular sperm extraction

(TESE), have led to men with Klinefelter's syndrome to produce

biological offspring. By 2010, over 100 successful pregnancies have been reported using IVF technology with surgically removed sperm material from males with KS.

Prognosis

The

lifespan of individuals with Klinefelter syndrome appears to be reduced

by approximately 2.1 years compared to the general male population. These results are still questioned data, are not absolute, and need further testing.

Epidemiology

This syndrome, evenly distributed in all ethnic groups, has a prevalence of one to two subjects per every 1000 males in the general population. However, it is estimated that only 25% of the individuals with Klinefelter syndrome are diagnosed throughout their lives. 3.1% of infertile males have Klinefelter syndrome. The syndrome is also the main cause of male hypogonadism.

History

The syndrome was named after American endocrinologist Harry Klinefelter, who in 1942 worked with Fuller Albright and E. C. Reifenstein at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and first described it in the same year.

The account given by Klinefelter came to be known as Klinefelter

syndrome as his name appeared first on the published paper, and

seminiferous tubule dysgenesis was no longer used. Considering the names

of all three researchers, it is sometimes also called

Klinefelter–Reifenstein–Albright syndrome. In 1956 it was discovered that Klinefelter syndrome resulted from an extra chromosome. Plunkett and Barr found the sex chromatin body in cell nuclei of the body. This was further clarified as XXY in 1959 by Patricia Jacobs and John Anderson Strong. The first published report of a man with a 47,XXY karyotype was by Patricia Jacobs and John Strong at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959.

This karyotype was found in a 24-year-old man who had signs of KS.

Jacobs described her discovery of this first reported human or mammalian

chromosome aneuploidy in her 1981 William Allan Memorial Award address.

Other animals

Klinefelter syndrome can also occur in other animals. In cats it can result in a male tortoiseshell and calico cat (patches of different colored fur), a pattern that is usually only seen in female cats. Not all cats with Klinefelter syndrome have tortoiseshell or calico patterns.