Grigori Rasputin

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name |

Григорий Ефимович Распутин

|

| Church | Russian Orthodox Church |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin |

| Born | 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 Pokrovskoye, Tyumensky Uyezd, Tobolsk Governorate (Siberia), Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916 (aged 47) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Parents |

|

| Spouse |

Praskovya Fedorovna Dubrovina (m. 1887)

|

| Children |

|

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (/ræˈspjuːtɪn/; Russian: Григорий Ефимович Распутин [ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪj jɪˈfʲiməvʲɪtɕ rɐˈsputʲɪn]; 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 – 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Emperor Nicholas II, the last monarch of Russia, and gained considerable influence in late imperial Russia.

Rasputin was born to a peasant family in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye in the Tyumensky Uyezd of Tobolsk Governorate (now Yarkovsky District of Tyumen Oblast). He had a religious conversion experience after taking a pilgrimage to a monastery in 1897. He has been described as a monk or as a "strannik" (wanderer or pilgrim), though he held no official position in the Russian Orthodox Church. He traveled to St. Petersburg in 1903 or the winter of 1904–05, where he captivated some church and social leaders. He became a society figure and met the tsar and Tsarina Alexandra in November 1905.

In late 1906, Rasputin began acting as a healer for the only son of Tsar Nicholas II, Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia. He was a divisive figure at court, seen by some Russians as a mystic, visionary, and prophet, and by others as a religious charlatan. The high point of Rasputin's power was in 1915 when Nicholas II left St. Petersburg to oversee Russian armies fighting World War I, increasing both Alexandra and Rasputin's influence. Russian defeats mounted during the war, however, and both Rasputin and Alexandra became increasingly unpopular. In the early morning of 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916, Rasputin was assassinated by a group of conservative noblemen who opposed his influence over Alexandra and the tsar.

Historians often suggest that Rasputin's terrible reputation helped discredit the tsarist government and thus helped precipitate the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty which happened a few weeks after he was assassinated. Accounts of his life and influence were often based on hearsay and rumor.

Early life

Pokrovskoye in 1912

Rasputin with his children

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of Pokrovskoye, along the Tura River in the Tobolsk Governorate (now Tyumen Oblast) in Siberia. According to official records, he was born on 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 and christened the following day. He was named for St. Gregory of Nyssa, whose feast was celebrated on 10 January.

There are few records of Rasputin's parents. His father, Yefim,

was a peasant farmer and church elder who had been born in Pokrovskoye

in 1842, and married Rasputin's mother, Anna Parshukova, in 1863. Yefim

also worked as a government courier, ferrying people and goods between Tobolsk and Tyumen

The couple had seven other children, all of whom died in infancy and

early childhood; there may have been a ninth child, Feodosiya. According

to historian Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin was certainly close to

Feodosiya and was godfather to her children, but "the records that have

survived do not permit us to say more than that".

According to historian Douglas Smith,

Rasputin's youth and early adulthood are "a black hole about which we

know almost nothing", though the lack of reliable sources and

information did not stop others from fabricating stories about his

parents and his youth after Rasputin's rise to fame.

Historians agree, however, that like most Siberian peasants, including

his mother and father, Rasputin was not formally educated and remained

illiterate well into his early adulthood.

Local archival records suggest that he had a somewhat unruly youth –

possibly involving drinking, small thefts, and disrespect for local

authorities – but contain no evidence of his being charged with stealing

horses, blasphemy, or bearing false witness, all major crimes that he

was later rumored to have committed as a young man.

In 1886, Rasputin travelled to Abalak, Russia, some 250 km east-northeast of Tyumen

and 2,800 km east of Moscow, where he met a peasant girl named

Praskovya Dubrovina. After a courtship of several months, they married

in February 1887. Praskovya remained in Pokrovskoye throughout

Rasputin's later travels and rise to prominence and remained devoted to

him until his death. The couple had seven children, though only three

survived to adulthood: Dmitry (b. 1895), Maria (b. 1898), and Varvara (b. 1900).

Religious conversion

In 1897, Rasputin developed a renewed interest in religion and left

Pokrovskoye to go on a pilgrimage. His reasons for doing so are unclear;

according to some sources, Rasputin left the village to escape

punishment for his role in a horse theft. Other sources suggest that he had a vision – either of the Virgin Mary or of St. Simeon of Verkhoturye

– while still others suggest that Rasputin's pilgrimage was inspired by

his interactions with a young theological student, Melity Zaborovsky.

Whatever his reasons, Rasputin's departure was a radical life change:

he was twenty-eight, had been married ten years, and had an infant son

with another child on the way. According to Douglas Smith, his decision

"could only have been occasioned by some sort of emotional or spiritual

crisis".

Rasputin had undertaken earlier, shorter pilgrimages to the Holy

Znamensky Monastery at Abalak and to Tobolsk's cathedral, but his visit

to the St. Nicholas Monastery at Verkhoturye in 1897 was transformative. There, he met and was "profoundly humbled" by a starets

(elder) known as Makary. Rasputin may have spent several months at

Verkhoturye, and it was perhaps here that he learned to read and write,

but he later complained about the monastery, claiming that some of the

monks engaged in homosexuality and criticizing monastic life as too

coercive.

He returned to Pokrovskoye a changed man, looking disheveled and

behaving differently than he had before. He became a vegetarian, swore

off alcohol, and prayed and sang much more fervently than he had in the

past.

Rasputin spent the years that followed living as a Strannik

(a holy wanderer, or pilgrim), leaving Pokrovskoye for months or even

years at a time to wander the country and visited a variety of holy

sites. It is possible that Rasputin wandered as far as Athos, Greece – the center of Eastern Orthodox monastic life – in 1900.

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a small circle of acolytes,

primarily family members and other local peasants, who prayed with him

on Sundays and other holy days when he was in Pokrovskoye. Building a

makeshift chapel in Efim's root cellar – Rasputin was still living

within his father's household at the time – the group held secret prayer

meetings there. These meetings were the subject of some suspicion and

hostility from the village priest and other villagers. It was rumored

that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting,

that the group sang strange songs that the villagers had not heard

before, and even that Rasputin had joined the Khlysty, a religious sect whose ecstatic rituals were rumored to include self-flagellation and sexual orgies.

According to historian Joseph Fuhrmann, however, "repeated

investigations failed to establish that Rasputin was ever a member of

the sect", and rumors that he was a Khlyst appear to have been

unfounded.

Rise to prominence

Makary, Bishop Theofan (Feofan) of Poltava and Rasputin

Word of Rasputin's activity and charisma began to spread in Siberia during the early 1900s. Sometime between 1902 and 1904, he travelled to the city of Kazan on the Volga river, where he acquired a reputation as a wise and perceptive starets, or holy man, who could help people resolve their spiritual crises and anxieties. Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers, he won over the father superior of the Seven Lakes Monastery outside Kazan, as well as a local church officials Archimandrite

Andrei and Bishop Chrysthanos, who gave him a letter of recommendation

to Bishop Sergei, the rector of the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary

at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, and arranged for him to travel to St. Petersburg, either in 1903 or in the winter of 1904–05.

Upon meeting Sergei at the Nevsky Monastery, Rasputin was introduced to church leaders, including Archimandrite Feofan,

who was the inspector of the theological seminary, was well-connected

in St. Petersburg society, and later served as confessor to the tsar and

his wife.

Feofan was so impressed with Rasputin that he invited him to stay in

his home and became one of Rasputin's most important and influential

friends in St. Petersburg.

According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin stayed in St.

Petersburg for only a few months on his first visit and returned to

Pokrovskoye in the fall of 1903.

Historian Douglas Smith, however, argues that it is impossible to know

whether Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg or returned to Pokrovskoye at

some point between his first arrival there and 1905. Regardless, by 1905 Rasputin had formed friendships with several members of the aristocracy, including the "Black Princesses", Militsa and Anastasia of Montenegro, who had married the tsar's cousins (Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich and Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich), and were instrumental in introducing Rasputin to the tsar and his family.

Rasputin first met the tsar on 1 November 1905, at the Peterhof Palace.

The tsar recorded the event in his diary, writing that he and

Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God – Grigory, from

Tobolsk province". Rasputin returned to Pokrovskoye shortly after their first meeting and did not return to St. Petersburg until July 1906. On his return, Rasputin sent Nicholas a telegram asking to present the tsar with an icon of Simeon of Verkhoturye. He met with Nicholas and Alexandra on 18 July and again in October, when he first met their children.

At some point, the royal family became convinced that Rasputin

possessed the power to heal Alexei, but historians disagree over when:

according to Orlando Figes, Rasputin was first introduced to the tsar

and tsarina as a healer who could help their son in November 1905,

while Joseph Fuhrmann has speculated that it was in October 1906 that

Rasputin was first asked to pray for the health of Alexei.

Healer to Alexei

Alexandra Feodorovna with her children, Rasputin and the nurse Maria Ivanova Vishnyakova (1908)

Much of Rasputin's influence with the royal family stemmed from the

belief by Alexandra and others that he had eased the pain and stopped

the bleeding of the tsarevich – who suffered from hemophilia – on

several occasions. According to historian Marc Ferro, the tsarina had a "passionate attachment" to Rasputin as a result of her belief that he could heal her son's affliction. Harold Shukman wrote that Rasputin became "an indispensable member of the royal entourage" as a result.

It is unclear when Rasputin first learned of Alexei's hemophilia, or

when he first acted as a healer for Alexei. He may have been aware of

Alexei's condition as early as October 1906,

and was summoned by Alexandra to pray for Alexei when he had an

internal hemorrhage in the spring of 1907. Alexei recovered the next

morning. Rasputin had been rumored to be capable of faith-healing since his arrival in St. Petersburg, and the tsarina's friend Anna Vyrubova

became convinced that Rasputin had miraculous powers shortly

thereafter. Vyrubova would become one of Rasputin's most influential

advocates.

During the summer of 1912, Alexei developed a hemorrhage in his

thigh and groin after a jolting carriage ride near the royal hunting

grounds at Spala, which caused a large hematoma. In severe pain and delirious with fever, the tsarevich appeared to be close to death. In desperation, the tsarina asked Vyrubova to send Rasputin (who was in Siberia) a telegram, asking him to pray for Alexei.

Rasputin wrote back quickly, telling the tsarina that "God has seen

your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will

not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much."

The next morning, Alexei's condition was unchanged, but Alexandra was

encouraged by the message and regained some hope that Alexei would

survive. Alexei's bleeding stopped the following day.

Historian Robert K. Massie has calls Alexei's recovery "one of the most mysterious episodes of the whole Rasputin legend".

The cause of his recovery is unclear: Massie speculated that Rasputin's

suggestion not to let doctors disturb Alexei had aided his recovery by

allowing him to rest and heal, or that his message may have aided

Alexei's recovery by calming Alexandra and reducing the emotional stress

on Alexei. Alexandra, however, believed that Rasputin had performed a miracle, and concluded that he was essential to Alexei's survival. Some writers and historians, such as Ferro, claim that Rasputin stopped Alexei's bleeding on other occasions through hypnosis.

Controversy

Rasputin among admirers, 1914

The royal family's belief that Rasputin possessed the power to heal Alexei brought him considerable status and power at court. The tsar appointed Rasputin his lampadnik

(lamplighter) who was charged with keeping the lamps lit that burned in

front of religious icons in the palace, and he thus had regular access

to the palace and royal family.

By December 1906, Rasputin had become close enough to the royal family

to ask a special favor of the tsar: that he be permitted to change his

surname to Rasputin-Novyi (Rasputin-New). Nicholas granted the request

and the name change was speedily processed, suggesting that the tsar

viewed and treated Rasputin favorably at that time. Rasputin used his status and power to full effect, accepting bribes and sexual favors from admirers

and working diligently to expand his influence. He soon became a

controversial figure; he was accused by his enemies of religious heresy

and rape, was suspected of exerting undue political influence over the

tsar, and was even rumored to be having an affair with the tsarina.

Alternative religious movements had become popular among the

city's aristocracy before Rasputin's arrival in St. Petersburg in 1903,

such as spiritualism and theosophy, and many of the aristocracy were intensely curious about the occult and the supernatural.

The Saint Petersburg elite were fascinated by Rasputin but did not

widely accept him. He did not fit in with the royal family, and he had a

very strained relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church. The Holy Synod frequently attacked Rasputin, accusing him of a variety of immoral or evil practices.

Rasputin with his wife and daughter Matryona (Maria) in his St. Petersburg apartment in 1911

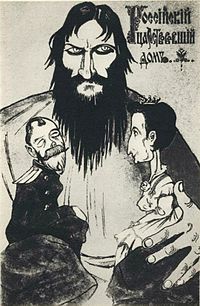

Caricature of Rasputin and the Imperial couple (1916)

World War I, the disappearance of feudalism,

and a meddling government bureaucracy all contributed to Russia's

declining economy at a very rapid rate. Many laid the blame with

Alexandra and with Rasputin, because of his influence over her. Here is

an example:

Vladimir Purishkevich was an outspoken member of the Duma. On 19 November 1916, Purishkevich made a rousing speech in the Duma, in which he stated, "The tsar's ministers who have been turned into marionettes, marionettes whose threads have been taken firmly in hand by Rasputin and the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna – the evil genius of Russia and the Tsarina… who has remained a German on the Russian throne and alien to the country and its people." Felix Yusupov attended the speech and afterwards contacted Purishkevich, who quickly agreed to participate in the murder of Rasputin.

Rasputin's influence over the royal family was used against him and

the Romanovs by politicians and journalists who wanted to weaken the

integrity of the dynasty, force the tsar to give up his absolute

political power, and separate the Russian Orthodox Church from the

state.

Assassination attempt

On 12 July [O.S. 29 June] 1914 a 33-year-old peasant woman named Chionya Guseva attempted to assassinate Rasputin by stabbing him in the stomach outside his home in Pokrovskoye. Rasputin was seriously wounded, and for a time it was not clear that he would survive. After surgery and some time in a hospital in Tyumen, he recovered.

Guseva was a follower of Iliodor, a former priest who had supported Rasputin before denouncing his sexual escapades and self-aggrandizement in December 1911.

A radical conservative and anti-semite, Iliodor had been part of a

group of establishment figures who had attempted to drive a wedge

between the royal family and Rasputin in 1911. When this effort failed,

Iliodor was banished from Saint Petersburg and was ultimately defrocked.

Guseva claimed to have acted alone, having read about Rasputin in the

newspapers and believing him to be a "false prophet and even an

Antichrist". Both the police and Rasputin, however, believed that Iliodor had played some role in the attempt on Rasputin's life.

Iliodor fled the country before he could be questioned about the

assassination attempt, and Guseva was found to be not responsible for

her actions by reason of insanity.

Death

Felix Yusupov (1914) married Irina Aleksandrovna Romanova, the Tsar's niece.

A group of nobles led by Prince Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and right-wing politician Vladimir Purishkevich

decided that Rasputin's influence over the tsarina had made him a

threat to the empire, and they concocted a plan in December 1916 to kill

him, apparently by luring him to the Yusupovs' Moika Palace.

Basement of the Yusupov Palace on the Moika in St. Petersburg where Rasputin was murdered

The wooden Bolshoy Petrovsky Bridge, from which Rasputin's body was thrown into the Malaya Nevka River

Rasputin was murdered during the early morning on 30 December [O.S.

17 December] 1916 at the home of Felix Yusupov. He died of three

gunshot wounds, one of which was a close-range shot to his forehead.

Little is certain about his death beyond this, and the circumstances of

his death have been the subject of considerable speculation. According

to historian Douglas Smith, "what really happened at the Yusupov home on

17 December will never be known". The story that Yusupov recounted in his memoirs, however, has become the most frequently told version of events.

Rasputin's body with bullet wound in forehead

Yusupov claimed that he invited Rasputin to his home shortly after

midnight and ushered him into the basement. Yusupov offered Rasputin tea

and cakes which had been laced with cyanide. Rasputin initially refused

the cakes but then began to eat them and, to Yusupov's surprise, he did

not appear to be affected by the poison. Rasputin then asked for some Madeira wine

(which had also been poisoned) and drank three glasses, but still

showed no sign of distress. At around 2:30 am, Yusupov excused himself

to go upstairs, where his fellow conspirators were waiting. He took a

revolver from Dmitry Pavlovich, then returned to the basement and told

Rasputin that he'd "better look at the crucifix and say a prayer",

referring to a crucifix in the room, then shot him once in the chest.

The conspirators then drove to Rasputin's apartment, with Sukhotin

wearing Rasputin's coat and hat in an attempt to make it look as though

Rasputin had returned home that night. They then returned to the Moika Palace and Yusupov went back to the basement to ensure that Rasputin was dead.

Suddenly, Rasputin leapt up and attacked Yusupov, who freed himself

with some effort and fled upstairs. Rasputin followed and made it into

the palace's courtyard before being shot by Purishkevich and collapsing

into a snowbank. The conspirators then wrapped his body in cloth, drove

it to the Petrovsky Bridge, and dropped it into the Malaya Nevka River.

Aftermath

News of Rasputin's murder spread quickly, even before his body was

found. According to Douglas Smith, Purishkevich spoke openly about

Rasputin's murder to two soldiers and to a policeman who was

investigating reports of shots shortly after the event, but he urged

them not to tell anyone else. An investigation was launched the next morning. The Stock Exchange Gazette

ran a report of Rasputin's death "after a party in one of the most

aristocratic homes in the center of the city" on the afternoon of 30

December [O.S. 17 December] 1916.

Two workmen noticed blood on the railing of the Petrovsky Bridge

and found a boot on the ice below, and police began searching the area.

Rasputin's body was found under the river ice on 1 January (O.S. 19

December) approximately 200 meters downstream from the bridge.

Dr. Dmitry Kosorotov, the city's senior autopsy surgeon, conducted an

autopsy. Kosorotov's report was lost, but he later stated that

Rasputin's body had shown signs of severe trauma, including three

gunshot wounds (one at close range to the forehead), a slice wound to

his left side, and many other injuries, many of which Kosorotov felt had

been sustained post-mortem.

Kosorotov found a single bullet in Rasputin's body but stated that it

was too badly deformed and of a type too widely used to trace. He found

no evidence that Rasputin had been poisoned.

According to both Douglas Smith and Joseph Fuhrmann, Kosorotov found no

water in Rasputin's lungs, and reports were incorrect that Rasputin had

been thrown into the water alive. Some later accounts claimed that Rasputin's penis had been severed, but Kosorotov found his genitals intact.

Rasputin was buried on 2 January (O.S. 21 December) at a small church that Anna Vyrubova had been building at Tsarskoye Selo.

The funeral was attended only by the royal family and a few of their

intimates. Rasputin's wife, mistress, and children were not invited, although his daughters met with the royal family at Vyrubova's home later that day. His body was exhumed and burned by a detachment of soldiers shortly after the tsar abdicated the throne in March 1917, in order to prevent his burial site from becoming a rallying point for supporters of the old regime.

Theory of British involvement

Some writers have suggested that agents of the British Secret Intelligence Service (BSIS) were involved in Rasputin's assassination.

According to this theory, British agents were concerned that Rasputin

was urging the tsar to make a separate peace with Germany, which would

allow Germany to concentrate its military efforts on the Western Front.

There are several variants of this theory, but they generally suggest

that British intelligence agents were directly involved in planning and

carrying out the assassination under the command of Samuel Hoare and Oswald Rayner, who had attended Oxford University with Yusopov, or that Rayner had personally shot Rasputin.

However, historians do not seriously consider this theory. According to

historian Douglas Smith, "there is no convincing evidence that places

any British agents at the murder scene". Historian Keith Jeffery

states that if British Intelligence agents had been involved in the

assassination of Rasputin, "I would have expected to find some trace of

that" in the Secret Intelligence Service archives, but no such evidence exists.

Daughter

Rasputin's daughter, Maria Rasputin (born Matryona Rasputina) (1898–1977), emigrated to France after the October Revolution and then to the United States. There, she worked as a dancer and then a lion tamer in a circus.