Anti-Arab racism, also called Anti-Arabism, Anti-Arab sentiment, or Arabophobia, refers to feelings and expressions of hostility, hatred, discrimination, fear, or prejudice toward Arab people, the Arab world or the Arabic language on the basis of an irrational disdain for their ethnic and cultural affiliation.

Notable historical instances of anti-Arab racism include the expulsion of the Moriscos from 1609 to 1614, the pacification of Algeria from 1830 to 1875, the Libyan Genocide from 1929 to 1934, the Nakba in Mandatory Palestine from 1947 to 1949, and the Zanzibar massacre in 1964. In the modern era, anti-Arabism is apparent in many nations, including the United States and Israel, as well as parts of Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas. In the United States, anti-Arab racism surged after the September 11 attacks, resulting in widespread racial profiling and hate crimes against Arab Americans. Arab citizens of Israel and Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories face institutionalized segregation and discrimination, which several scholars have characterized as a form of apartheid. Various advocacy organizations have been formed to protect the civil rights of individuals of Arab descent in the United States, such as the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee and the Council on American–Islamic Relations.

Definition of Arab

Arabs are people whose native language is Arabic. People of Arabic origin, in particular native English and French speakers of Arab ancestry in Europe and the Americas, often identify themselves as Arabs. Due to widespread practice of Islam among Arab populations, Anti-Arabism is commonly confused with Islamophobia.

There are prominent Arab non-Muslim minorities in the Arab world. These minorities include the Arab Christians in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait and Bahrain, among other Arab countries. There are also sizable minorities of Arab Jews, Druze, Baháʼí, and nonreligious people.

Historical anti-Arabism

Anti-Arab prejudice is suggested by many events in history. In the Iberian Peninsula, when the Reconquista by the indigenous Christians from the Moorish colonists was completed with the fall of Granada, all non-Catholics were expelled. In 1492, Arab converts to Christianity, called Moriscos, were expelled from Spain to North Africa after being condemned by the Spanish Inquisition. The Spanish word "moro", meaning moor, today carries a negative meaning.

After the annexation of the Muslim-ruled state of Hyderabad by India in 1948, about 7,000 Arabs were interned and deported.

The Zanzibar Revolution of January 12, 1964, ended the local Arab dynasty. As many as 17,000 Arabs were exterminated by black African revolutionaries, according to reports, and thousands of others fled the country.

In The Arabic Language and National Identity: a Study in Ideology, Yasir Suleiman notes of the writing of Tawfiq al-Fikayki that he uses the term shu'ubiyya to refer to movements he perceives to be anti-Arab, such as the Turkification movement in the Ottoman Empire, extreme-nationalist and Pan-Iranist movements in Iran and communism. The economic boom in Iran which lasted until 1979 led to an overall increase of Iranian nationalism sparking thousands of anti-Arab movements. In al-Fikayki's view, the objectives of anti-Arabism are to attack Arab nationalism, pervert history, emphasize Arab regression, deny Arab culture, and generally be hostile to all things Arab. He concludes that, "In all its various roles, anti-Arabism has adopted a policy of intellectual conquest as a means of penetrating Arab society and combatting Arab nationalism."

In early 20th and late 19th century when Palestinians and Syrians migrated to Latin America Arabophobia was common in these countries.

Modern anti-Arabism

Algeria

Anti-Arabism is a major element of movements known as Berberism that are widespread mainly amongst Algerians of Kabyle and other Berber origin. It has historic roots as Arabs are seen as invaders that occupied Algeria and destroyed its late Roman and early medieval civilization that was considered an integral part of the West; this invasion is considered to have been the source of the resettlement of Algeria's Berber population in Kabylie and other mountainous areas. Regardless, the Kabyles and other Berbers have managed to preserve their culture and achieve high standards of living and education. Furthermore, many Berbers speak their language and French; are non religious, secular, or Evangelical Christian; and openly identify with the Western World. Many Berber Nationalists view Arabs as a hostile people intent on eradicating their own culture and nation. Berber social norms restrict marriage to someone of Arab ethnicity, although it is permitted to marry someone from other ethnic groups.

According to Lawrence Rosen, ethnic background is not a crucial factor in marriage between members of each group in North Africa, when compared to social and economic backgrounds. There are regular Hate incidents between Arabs and Berbers and Anti-Arabism has been accentuated by the Algerian government's anti-Berber policies. Contemporary relations between Berbers and Arabs are sometimes tense, particularly in Algeria, where Berbers rebelled (1963–65, 2001) against Arab rule and have demonstrated and rioted against their cultural marginalization in the new founded state.

The Anti-Arab sentiments among Algerian Berbers (mainly from Kabylie) were always related to the reassertion of Kabyle identity. It began as an intellectual militant movement in schools, universities, and popular culture (mainly nationalistic songs). In addition to that, the authorities' efforts to promote development in Kabylie contributed to a boom of sorts in Tizi Ouzou, whose population almost doubled between 1966 and 1977, and to a greater degree of economic and social integration within the region had the contrary effect of strengthening a collective Berber consciousness and Anti-Arab sentiments.

Arabophobia can be seen at different levels of intellectual, social, and cultural life of some Berbers. After the Berberist crisis in 1949, a new radical intellectual movement emerged under the name L'Académie Berbère. This movement was known by its adoption and promotion of Anti-Arab and Anti-Islam ideologies especially amongst immigrant Kabyles in France and achieved a relative success at the time.

In 1977, the final game of the national soccer championship pitting a team from Kabylie against one from Algiers turned into an Arab-Berber conflict. The Arab national anthem of Algeria was overwhelmed by the shouting of Anti-Arab slogans such as "A bas les arabes" (down with the Arabs).

The roots of modern-day Arabophobia in Algeria can be traced back to multiple factors. For some, Anti-Arabism movement among Berbers is part of the legacy of French Colonization or manipulation of North Africa. As from the beginning, the French understood that to attenuate Muslim resistance to their presence, mainly in Algeria, they had to resort to the divide and rule doctrine. The most obvious divide that could be instrumentalized in this perspective was the ethnic one. Therefore, France employed some official colonial practices to tighten its control over Algeria by creating racial tensions between Arabs and Berbers and between Jews and Muslims.

Others argue that the Berber language and traditions are deeply rooted in the North African cultural mosaic; for centuries, Berber culture has survived conquests, repression, and exclusion from different invaders: Romans, Arabs, and French. Hence, believing that its identity and specificity were threatened, the Berbers took note of the political and ideological implications of Arabism as defended by successive governments. Gradual radicalization and Anti-Arab sentiments began to emerge in Algeria and among the hundreds of thousands of Berbers in France who had been in the forefront of the Berber cultural movement.

Australia

The Cronulla riots in Sydney, Australia in December 2005 have been described as "anti-Arab racism" by community leaders. NSW Premier Morris Iemma said the violence revealed the "ugly face of racism in this country".

A 2004 report by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission said that more than two-thirds of Muslim and Arab Australians say they have experienced racism or racial vilification since the September 11 attacks and that 90% of female respondents experienced racial abuse or violence.

Adam Houda, a Lebanese Muslim lawyer, has been repeatedly harassed by the New South Wales police force. Houda has been arrested or detained six times in 11 years and has sued the police force for malicious prosecution and harassment three times. Houda claims that the police's motivation is racism which he says is "alive and well" in Bankstown. He has been stopped going to prayers, with relatives and friends and has been subjected to a humiliating body search. He has been the object of several groundless accusations of robbery or holding a knife. A senior lawyer told the Sydney Morning Herald that the police harassment was due to the police enmity against Houda's clients and the Australian Arab community. He was first falsely arrested in 2000 for which he was awarded $145,000 damages by a judge who described his persecution as "shocking". Constable Lance Stebbing was found to have maliciously arrested Houda, as well as using profanities against him and approaching him in a "menacing manner". Stebbing was supported by other police, against the testimony of many eyewitnesses. In 2005, Houda accused the police of disabling his mobile phone making it difficult to perform his work as a criminal defense lawyer.

In 2010, Houda, his lawyer Chris Murphy, and Channel Seven journalist Adam Walters claimed that Frank Menilli, a senior New South Wales police officer, behaved in a corrupt fashion by trying to alter Channel Seven's coverage of the Houda Case by promising Walters inside information in exchange for presenting the case in the police's favour. Walters regarded the offer as an "attempted bribe". The latest incident occurred in 2011, when Houda was arrested for refusing a frisk search and resisting arrest after having been approached by police suspecting him of involvement in a recent robbery. These charges were thrown out of court by Judge John Connell who stated "At the end of the day, here were three men of Middle Eastern appearance walking along a suburban street, for all the police knew, minding their own business at an unexceptional time of day, in unexceptional clothing, except two of the men had hooded jumpers. The place they were in could not have raised a reasonable suspicion they were involved in the robberies" Houda is currently suing the six police officers involved for false imprisonment, unlawful arrest, assault and battery and defamation. One of the six is an assistant commissioner. He is seeking $5 million in damages.

France

France used to be a colonial empire, with still great post-colonial power over its former colonies, using Africa as a reservoir for labor, especially in moments of dire need. During World War I, reconstruction and shortages made France bring thousands of North African workers. Out of a total of 116,000 workers from 1914 to 1918, 78,000 Algerians, 54,000 Moroccans, and Tunisians were requisitioned. Two hundred and forty thousand Algerians were mobilized or drafted, and two thirds of these were soldiers who served mostly in France. This constituted more than one-third of the men of those nations from ages 20–40. According to historian Abdallah Laroui, Algeria sent 173,000 soldiers, 25,000 of whom were killed. Tunisia sent 56,000, of whom 12,000 were killed. Moroccan soldiers helped defend Paris and landed at Bordeaux in 1916.

After the war, reconstruction and labor shortages necessitated even larger number of Algerian laborers. Migration (or the need for labor) was reestablished at a high level by 1936. This was partly the result of collective recruitments in the villages conducted by French officers and representatives of companies. Labor recruitment continued throughout the 1940s. North Africans were mostly recruited for dangerous and low-wage jobs, unwanted by ordinary French workers.

This large number of immigrants was of great help for France's rapid post–World War II economic growth. The 1970s were marked by recession followed by the cessation of labor migration programs and crackdowns on illegal immigration. During the 1980s, political disfavor with President Mitterrand's social programs led to the rise of Jean-Marie Le Pen and other far right French nationalists. The public increasingly blamed immigrants for French economic problems. In March 1990, according to a poll reported in Le Monde, 76% of those polled said that there were too many Arabs in France while 39% said they had an "aversion" to Arabs. In the following years, Interior Minister Charles Pasqua was noted for dramatically toughening immigration laws.

In May 2005, riots broke out between North Africans and Romani people in Perpignan, after a young Arab man was shot dead and another Arab man was lynched by a group of Roma.

Chirac's controversial "Hijab ban" law, presented as secularization of schools, was interpreted by its critics as an "indirect legitimization of anti-Arab stereotypes, fostering rather than preventing racism."

A higher rate of racial profiling is conducted on Blacks and Arabs by the French police.

Iran

Human rights group Amnesty International says that in practice, Arabs are among a number of ethnic minorities that are disadvantaged and suffer discrimination by the authorities. Separatist tendencies in Khuzestan exacerbate this. How far the situation facing Arabs in Iran is related to racism or simply a result of policies suffered by all Iranians is a matter of debate (see: Politics of Khuzestan). Iran is a multi-ethnic society with its Arab minority mainly located in the south.

It is claimed by some that anti-Arabism in Iran may be related to the notion that Arabs forced some Persians to convert to Islam in 7th century AD (See: Muslim conquest of Persia). Author Richard Foltz in his article "Internationalization of Islam" states "Even today, many Iranians perceive the Arab destruction of the Sassanid Empire as the single greatest tragedy in Iran's long history. Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, many Iranians (also known as "mawali") came to despise the Umayyads due to discrimination against them by their Arab rulers. The Shu'ubiyah movement was intended to reassert Iranian identity and resist attempts to impose Arab culture while reaffirming their commitment to Islam.

More recently, anti-Arabism has arisen as a consequence of aggression against Iran by the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. During a visit to Khuzestan, which has most of Iran's Arab population, a British journalist, John R. Bradley, wrote that despite the fact that the majority of Arabs supported Iran in the war, "ethnic Arabs complain that, as a result of their divided loyalties during the Iran–Iraq War, they are viewed more than ever by the clerical regime in Tehran as a potential fifth column, and suffer from a policy of discrimination." However, Iran's Arab population played an important role in defending Iran during the Iran-Iraq War and most refused to heed Saddam Hussein's call for an uprising and instead fought against their fellow Arabs. Furthermore, Iran's former defense minister Ali Shamkhani, a Khuzestani Arab, was chief commander of the ground force during the Iran-Iraq War as well as serving as first deputy commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The Arab minority of southern Iran has been subject to discriminations, persecution in Iran. In a report published in February 2006, Amnesty International stated that the "Arab population of Iran is one of the most economically and socially deprived in Iran" and that Arabs have "reportedly been denied state employment under the gozinesh [job placement] criteria."

Furthermore, land expropriation by the Iranian authorities is reportedly so widespread that it appears to amount to a policy aimed at dispossessing Arabs of their traditional lands. This is apparently part of a strategy aimed at the forcible relocation of Arabs to other areas while facilitating the transfer of non-Arabs into Khuzestan and is linked to economic policies such as zero-interest loans which are not available to local Arabs.

— Amnesty International

Critics of such reports have pointed out that they are often based on sketchy sources and are not always to be trusted at face value (see: Criticism of human rights reports on Khuzestan). Furthermore, critics point out that Arabs have social mobility in Iran, with a number of famous Iranians from the worlds of arts, sport, literature, and politics having Arab origins (see: Iranian Arabs) illustrating Arab-Iranian participation in Iranian economics, society, and politics. They contend that Khuzestan province, where most of Iran's Arabs live, is actually one of the more economically advanced provinces of Iran, more so than many of the Persian-populated provinces.

Some critics of the Iranian government contend that it is carrying out a policy of anti-Arab ethnic cleansing. While there has been large amounts of investment in industrial projects such as the Razi Petrochemical Complex, local universities, and other national projects such as hydroelectric dams (such as the Karkheh Dam, which cost $700 million to construct) and nuclear power plants, many critics of Iran's economic development policies have pointed to the poverty suffered by Arabs in Khuzestan as proof of an anti-Arab policy agenda. Following his visit to Khuzestan in July 2005, UN Special Rapporteur for Adequate Housing Miloon Kothari spoke of how up to 250,000 Arabs had been displaced by such industrial projects and noted the favorable treatment given to settlers from Yazd compared to the treatment of local Arabs.

However, it is also true that non-Arab provinces such as Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Sistan and Baluchestan Province, and neighboring Īlām Province also suffer high levels of poverty, indicating that government policy is not disadvantaging Arabs alone but other regions, including some with large ethnically Persian populations. Furthermore, most commentators agree that Iran's state-controlled and highly subsidized economy is the main reason behind the inability of the Iranian government to generate economic growth and welfare at ground levels in all cities across the nation, rather than a state ethnic policy targeted specifically at Arabs; Iran is ranked 156th on The Heritage Foundation's 2006 Index of Economic Freedom.

In the Iranian education system, after primary education cycle (grades 1-5 for children 6 to 11 years old), passing some Arabic courses is mandatory until the end of secondary education cycle (grade 6 to Grade 12, from age 11 to 17). In higher education systems (universities), passing Arabic language courses is selective.

Persians use slurs like "Tazi Kaseef" (lit. Dirty Taazi), "Arabe malakh-khor" (عرب ملخخور) (lit. Locust-eater Arab), "soosmar-khor" (سوسمارخور) (lizard eater) and call Arabs "پابرهنه" (lit. barefoot), "بیتمدن" (lit. uncivilized), "وحشی" (lit. barbarians) and "زیرصحرایی" (lit sub-saharan). Anti-Islamist government Persians refer to Persian Islamic Republic supporters from Hezbollahi families as Arab-parast (عربپرست) (lit. Arab Worshipper). Arabs use slurs against Persians by calling them Fire-worshipers and majoos, "Majus" (مجوس) (Zoroastrians, Magi).

Negative views Persians have of Arabs include eating habits such as Arabs eating lizards.

In Iran, there is a saying, The Arab of the desert eats locusts, while the dogs of Isfahan drink ice-cold water. (عرب در بیابان ملخ میخورد سگ اصفهان آب یخ میخورد). In Iran "to be outright Arab" (از بیخ عرب بودن) means "to be a complete idiot".

Relations are uneasy between specifically Iran and the Persian Gulf Arab countries in particular. Persians and Arabs dispute the name of the Persian Gulf. The Greater and Lesser Tunbs are disputed between the two countries. A National Geographic reporter who interviewed Iranians reported that many of them frequently said We are not Arabs!" "We are not terrorists!".

The Iranian rap artist Behzad Pax released a song in 2015 called "Arab-Kosh" (عربكش) (Arab-killer) which was widely reported on the Arab media who claimed that it was released with the approval of the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. The Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance denied that it gave approval to the song and condemned it as a product of a "sick mind".

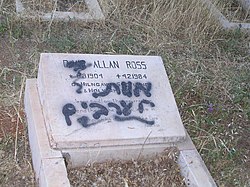

Israel

As a consequence of the Arab–Israeli conflict, there is a high level of hostility between sections of the Jewish and Arab societies in Israel. A group of men in Pisgat Ze'ev started patrolling the neighborhood to stop Jewish women from dating Arab men. The municipality of Petah Tikva has a telephone hotline to inform on Jewish girls who date Arab men, as well as a psychological counseling service. Kiryat Gat launched a school programme to warn Jewish girls against dating local Bedouin men.

Geography textbooks used in Israeli schools were found to portray Arabs as primitive and backwards, with the Nakba, the destruction of Palestinian society in the 1948 Palestine war, disregarded entirely. History textbooks likewise portrayed the Palestinian population negatively, showing them as primitive and collectively to be an enemy. Contrasted with the portrayal of Jews, who were shown to be heroic and progressive, Israeli textbooks delegitimized Arabs and used negative stereotyping of Arabs nearly uniformly.

The Bedouin representatives submitted a report to the United Nations claiming that they are not treated as equal citizens and Bedouin towns are not provided the same level of services, land and water as Jewish towns of the same size are. The city of Beersheba refused to recognize a Bedouin holy site despite a High Court recommendation.

In 1994, a Jewish settler in the West Bank and follower of the Kach party, Baruch Goldstein, massacred 29 Palestinian Muslim worshipers at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. It was known that, prior to the massacre, Goldstein, a physician, refused to treat Arabs, including Arab soldiers with the Israeli army. During his funeral, a rabbi declared that even one million Arabs are "not worth a Jewish fingernail". Goldstein was immediately "denounced with shocked horror even by the mainstream Orthodox", and many in Israel classified Goldstein as insane. The Israeli government condemned the massacre and made Kach illegal. The Israeli army killed a further nine Palestinians during riots following the massacre, and the Israeli government severely restricted Palestinian freedom of movement in Hebron, while letting settlers and foreign tourists roam free, although Israel also forbade a small group of Israeli settlers from entering Palestinian towns and demanded that those settlers turn in their army-issued rifles. Goldstone's grave has become a pilgrimage site for Jewish extremists.

In a number of occasions, Israeli Jewish demonstrators and rioters used racist anti-Arab slogans. For example, during the Arab riots in October 2000 events, Israelis counter-rioted in Nazareth and Tel Aviv, throwing stones at Arabs, destroying Arab property, with some chanting "death to Arabs". Some Israeli-Arab soccer players face chants from the crowd when they play such as "no Arabs, no terrorism". In the most radical event, Abbas Zakour, an Arab member of the Knesset, was stabbed and wounded by unidentified men, who shouted anti-Arab chants. The attack was described as a "hate crime". Among the Israeli teams, Beitar Jerusalem is considered emblematic of Jewish racism; the fans are infamous for their 'Death to Arabs' chant and the team has a ban on Arab players, a policy that is in violation of FIFA's guidelines, though the team has never faced suspension from the football organization. In March 2012, supporters of the team were filmed raiding a Jerusalem mall and beating up Arab employees.

The Israeli political party Yisrael Beiteinu, whose platform includes the redrawing of Israel's borders so that 500,000 Israeli Arabs would be part of a future Palestinian State, won 15 seats in the 2009 Israeli elections, increasing its seats by 4 compared to the 2006 Israeli elections. This policy, also known as the Lieberman Plan, was described as "anti-Arab" by The Guardian. In 2004, Yehiel Hazan, a member of the Knesset, described the Arabs as worms: "You find them everywhere like worms, underground as well as above."

In 2004, then Deputy Defense Minister Ze'ev Boim asked "What is it about Islam as a whole and the Palestinians in particular? Is it some form of cultural deprivation? Is it some genetic defect? There is something that defies explanation in this continued murderousness."

In August 2005, Israeli soldier Eden Natan-Zada traveled to an Israeli Arab town and massacred four civilians. Israeli Arabs said they would draw up a list of grievances after the terrorist attack of Eden Natan-Zada. "This was a planned terror attack and we find it extremely difficult to treat it as an individual action," Abed Inbitawi, an Israeli-Arab spokesman, told The Jerusalem Post. "It marks a certain trend that reflects a growing tendency of fascism and racism in Israeli society generally as well as the establishment towards the minority Arab community," he said.

According to a 2006 poll conducted by Geocartographia for the Centre for the Struggle Against Racism, 41% of Israelis support Arab-Israeli segregation at entertainment venues, 40% believed "the state needs to support the emigration of Arab citizens", and 63% believed Arabs to be a "security and demographic threat" to Israel. The poll found that more than two thirds would not want to live in the same building as an Arab, 36% believed Arab culture to be inferior, and 18% felt hatred when they heard Arabic spoken.

In 2007, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel reported that anti-Arab views had doubled, and anti-Arab racist incidents had increased by 26%. The report quoted polls that suggested 50% of Jewish Israelis do not believe Arab citizens of Israel should have equal rights, 50% said they wanted the government to encourage Arab emigration from Israel, and 75% of Jewish youths said Arabs were less intelligent and less clean than Jews. The Mossawa Advocacy Center for Arab Citizens in Israel reported a tenfold increase in racist incidents against Arabs in 2008. Jerusalem reported the highest number of incidents. The report blamed Israeli leaders for the violence, saying "These attacks are not the hand of fate, but a direct result of incitement against the Arab citizens of this country by religious, public, and elected officials."

In March 2009, following the Gaza War, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) drew criticism when several young soldiers had T-shirts printed up privately with slogans and caricatures portraying dead babies, weeping mothers, and crumbled mosques.

In June 2009, Haaretz reported that Israel's Public Security Minister, Yitzhak Aharonovich, called an undercover police officer a "dirty Arab" whilst touring Tel Aviv.

Since the 2000s, groups such as Lehava have been formed in Israel to prevent that Israeli Arab men form relationships with Jewish women. Some of the material promoted to discourage Jewish women to be with Arab men, are sanctioned by local governments and police departments. Lehava has received permission from Israeli courts to picket the weddings uniting a Palestinian and a Jewish partner.

In 2010, dozens of Israel's top rabbis went on to sign a document forbidding that Jews rent apartments to Arabs, saying that "racism originated in the Torah".

In January 2012, the Israeli High Court upheld a decision, deemed racist, preventing the Palestinian espouses of Israeli Arabs from obtaining Israeli citizenship or resident status.

A poll in 2012 revealed that racist attitudes are embraced by a large majority of Israelis. 59% of Jews said they wanted Jews to be given preference in admission to public employment, 50% wanted the state to generally treat Jews better than Arabs, and over 40% wanted separate housing for Jews and Arabs. According to the poll, 58% supported the use of the term apartheid to represent Israeli policies against Arabs. The poll also showed that the majority of Israeli Jews would not want voting rights extended to Palestinians if the West Bank were annexed by Israel.

In 2013, Nazareth Illit mayor Shimon Gafsou declared that he would never allow that an Arab school, a mosque, or a church be built in his city, despite the fact that Arabs account for 18 percent of its population.

On July 2, 2014, 16-year-old Palestinian Mohammed Abu Khdeir was kidnapped, beaten and burned alive, after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped and killed in the West Bank. Khdeir's family members have blamed Israeli Government anti-Arab hate speech for inciting the murder and rejected the PM's condolence message, as well as a visit by then President Shimon Peres. Two Israeli minors were found guilty of Khdeirs' murder and sentenced to life and 21 years imprisonment respectively.

During the 2015 Israeli legislative election, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu complained, in a video statement to supporters, that his left-wing opponents were supposedly sending Israeli Arabs to vote in droves, in a statement that was widely condemned as racist, including by the US government. Netanyahu went on to win the elections against poll predictions, and several commentators and pollster imputed his victory to his last-minute attack on Israeli Arab voters. During election campaign, then Foreign Affairs Minister Avigdor Lieberman proposed beheading Israeli Arabs that are "disloyal" to the state.

Niger

In October 2006, the government of Niger announced that it would deport the Mahamid Baggara Arabs living in the Diffa region of eastern Niger to Chad. This population numbered about 150,000. While the government was rounding Arabs in preparation for the deportation, two girls died, reportedly after fleeing government forces, and three women suffered miscarriages. Niger's government had eventually suspended the controversial decision to deport Arabs.

Turkey

Turkey has a history of strong anti-Arabism. During the Ottoman Empire, the Arabs were treated as just second-class subjects and suffered from immense discrimination by the Ottoman Turkish rulers, in addition, most of government's main positions were either held by Turks or non-Arab people, except for the Emirate of Hejaz under Ottoman rule. Future policy of anti-Arab sentiment, including the process of Turkification, led to the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans.

Because of the Syrian refugee crisis, anti-Arabism has intensified. Haaretz reported that anti-Arab racism in Turkey mainly affects two groups; tourists from the Gulf who are characterized as "rich and condescending" and the Syrian refugees in Turkey. Haaretz also reported that anti-Syrian sentiment in Turkey is metastasizing into a general hostility toward all Arabs including the Palestinians. Deputy Chairman of the Good Party warned that Turkey risked becoming "a Middle Eastern country" because of the influx of refugees.

Outside historical enmity, anti-Arabism is also widespread in Turkish media, as Turkish media and education curriculum associating Arabs with backwardness. This has continued influencing modern Turkish historiography and the crusade of Turkish soft power, with Arabs being frequently stereotyped as evil, uncivilized, terrorists, incompetent, etc. This depiction is frequently used in contrast to the alleged depiction of Turkic people as "noble, generous, fearsome, loyal, brave and spirited warriors".

Anti-Arab sentiment is also further fueled by ultranationalist groups, including the Grey Wolves and pan-Turkist nationalist parties, who called for invasions on the Arab World's Syria and Iraq, to prevent the ongoing Arab persecution of its Turkic populations in many Arab countries of the Middle East. Subsequently, Turkey has begun a series of persecuting its Arab population, as well as desire to recreate the new Turkish border.

In recent years, anti-Arabism has been linked with various attempts by Arab leaders to meddle into Turkish affairs, Turkey's alliance with Israel, which led to the discrimination against Arabs in Turkey grow.

United Kingdom

In 2008, a Qatari 16-year-old was killed in a racially motivated attack in Hastings, East Sussex.

United States

William A. Dorman, writing in the compendium The United States and the Middle East: A Search for New Perspectives (1992), notes that whereas "anti-Semitism is no longer socially acceptable, at least among the educated classes[, n]o such social sanctions exist for anti-Arabism." Public opinion polls demonstrate that anti-Arabism in the United States is increasing significantly.

Prominent Russian-American Objectivist author, scholar and philosopher Ayn Rand, in her 1974 Ford Hall Forum lecture, explained her support for Israel following the Yom Kippur War of 1973 against a coalition of Arab nations, expressing strong anti-Arab sentiment, saying: "The Arabs are one of the least developed cultures. They are typically nomads. Their culture is primitive, and they resent Israel because it's the sole beachhead of modern science and civilization on their continent. When you have civilized men fighting savages, you support the civilized men, no matter who they are."

During the 1991 Gulf War, hostility toward Arabs increased in the United States. Arab Americans have experienced a backlash as result of terrorist attacks, including events where Arabs were not involved, like the Oklahoma City bombing, and the explosion of TWA Flight 800. According to a report prepared by the Arab American Institute, three days after the Oklahoma City bombing "more than 200 serious hate crimes were committed against Arab Americans and American Muslims. The same was true in the days following September 11."

According to a 2001 poll of Arab Americans conducted by the Arab American Institute, 32% of Arab Americans reported having been subjected to some form of ethnic-based discrimination during their lifetimes, while 20% reported having experienced an instance of ethnic-based discrimination since the September 11 attacks. Of special concern, for example, is the fact that 45% of students and 37% of Arab Americans of the Muslim faith report being targeted by discrimination since September 11.

According to the FBI and Arab groups, the number of attacks against Arabs and Muslims, as well as others mistaken for them, rose considerably after the 9/11 attacks. Hate crimes against people of Middle Eastern origin or descent increased from 354 attacks in 2000, to 1,501 attacks in 2001. Among the victims of the backlash was a Middle Eastern man in Houston, Texas who was shot and wounded after an assailant accused him of "blowing up the country", and four immigrants shot and killed by a man named Larme Price, who confessed to killing them as revenge for the September 11 attacks. Although Price described his victims as Arabs, only one was from an Arab country. This appears to be a trend; because of stereotypes of Arabs, several non-Arab, non-Muslim groups were subjected to attacks in the wake of 9/11, including several Sikh men attacked for wearing their religiously mandated turban.

Earl Krugel and Irv Rubin, two leaders of the Jewish Defense League (JDL), described by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security as a terrorist organization, planned to bomb Arab-American Congressman Darrell Issa's office and the King Fahd Mosque in Culver City, California. The two were arrested as part of a sting operation when they received a shipment of explosives at Krugel's home in Los Angeles. Krugel was murdered in November 2005 while in the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons in Phoenix. His conviction, which was under appeal at that time, was dismissed in U.S. District Court. Rubin committed suicide in 2002 while in Federal Bureau of Prisons custody in Los Angeles. Although the JDL was suspected in the 1985 bombing death of ADC leader Alex Odeh, no arrest has been made in that case.

Stephen E. Herbits, the Secretary-General of the New York–based World Jewish Congress (WJC) made several racist remarks and ethnic slurs in an internal memo against the president of the European Jewish Congress Pierre Besnainou: "He is French. Don't discount this. He cannot be trusted ... He is Tunisian. Do not discount this either. He works like an Arab." The WJC in Israel has condemned the statements as both hateful and racist. "It appears that the struggle in the World Jewish Congress has now turned racist, said Knesset member Shai Hermesh (Kadima), who heads the Israeli board of the WJC. Instead of creating unity among the Jewish people, this organization is just creating division and hatred."

In 2004, American radio host Michael Savage described Arabs as "non-humans", said that Americans want the U.S. to "drop a nuclear weapon" on an Arab country, and advocated that people in the Middle East be "forcibly converted to Christianity" to "turn them into human beings". Savage characterized Israel as "a little country surrounded by racist, fascist bigots who don't want anyone but themselves living in that hell hole called the Middle East". Expressions of anti-Arabism in the United States intensified following the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, which was perpetrated by Nidal Hasan, a Palestinian Arab American. In 2010, the proposed development of an Islamic community center containing a mosque near the World Trade Center site provoked further widespread expressions of virulent anti-Arabism in the United States.

Western media

Parts of Hollywood are regarded as using a disproportionate number of Arabs as villains and of depicting Arabs negatively and stereotypically. According to Godfrey Cheshire, a critic on the New York Press, "the only vicious racial stereotype that's not only still permitted but actively endorsed by Hollywood" is that of Arabs as crazed terrorists.

Like the image projected of Jews in Nazi Germany, the image of Arabs projected by western movies is often that of "money-grubbing caricatures that sought world domination, worshipped a different God, killed innocents, and lusted after blond virgins".

The 2000 film Rules of Engagement drew criticism from Arab groups and was described as "probably the most racist film ever made against Arabs by Hollywood" by the ADC. Paul Clinton of The Boston Globe wrote "at its worst, it's blatantly racist, using Arabs as cartoon-cutout bad guys".

Jack Shaheen, in his book Reel Bad Arabs, surveyed more than 900 film appearances of Arab characters. Of those, only a dozen were positive and 50 were balanced. Shaheen writes that "[Arab] stereotypes are deeply ingrained in American cinema. From 1896 until today, filmmakers have collectively indicted all Arabs as Public Enemy #1 – brutal, heartless, uncivilized religious fanatics and money-mad cultural "others" bent on terrorizing civilized Westerners, especially [Christians] and [Jews]. Much has happened since 1896 ... Throughout it all, Hollywood's caricature of the [Arab] has prowled the silver screen. He is there to this day – repulsive and unrepresentative as ever."

According to Newsweek columnist Meg Greenfield, anti-Arab sentiment presently promotes misconceptions about Arabs and hinders genuine peace in the Middle East.

In 1993, the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee confronted Disney about anti-Arab racist content in its animated film Aladdin. At first Disney denied any problems but eventually relented and changed two lines in the opening song. Members of the ADC were still unhappy with the portrayal of Arabic characters and the referral to the Middle East as "barbaric".

In 1980, The Link, a magazine published by Americans for Middle East Understanding, contained an article "The Arab Stereotype on Television" which detailed negative Arab stereotypes that appeared in TV shows including Woody Woodpecker, Rocky and Bullwinkle, Jonny Quest and an educational children's show on PBS.

Arab advocacy organisations

United States

The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) was founded in 1980 by United States Senator James Abourezk. The ADC claims that it is the largest Arab-American grassroots civil rights organization in the United States. Warren David is the national president of ADC. On March 1, 2010, Sara Najjar-Wilson replaced former Democratic US Congresswoman Mary Rose Oakar as president. ADC claims that is at the forefront in addressing anti-Arabism - discrimination and bias against Arab Americans.

Founded in 1985 by James Zogby, a prominent Democrat, the Arab American Institute (AAI) states that it is a partisan non-profit, membership organization and advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. that focuses on the issues and interests of Arab-Americans nationwide. The AAI also conducts research related to anti-Arabism in the United States. The Anti-Defamation League identifies the Arab American Institute as an anti-Israel protest organization. According to an AAI 2007 poll of Arab-Americans:

Experiences of discrimination are not uniform within the Arab American community, with 76% of young Arab Americans (18 to 29 years old) and 58% of Arab American Muslims reporting that they have "personally experienced discrimination in the past because of [their] ethnicity," as opposed to 42% of respondents overall... . Comparisons with previous AAI polls in which this same question was asked indicate a rise in experiences of discrimination amongst young Arab Americans.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) is an Islamic organization in North America that was created in June 1994. It has been active against anti-Arabism as well.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), which was founded to combat antisemitism and other forms of bigotry, actively investigated and spoke out against the rise in anti-Arab hate crimes following the September 2001 terrorist attacks. In 2003, the ADL urged the Speaker of the United States' House of Representatives to approve a resolution condemning bigotry and violence against Arab-Americans and American Muslims. The American Jewish Committee, and American Jewish Congress have issued similar responses. In 2004, the ADL national director issued the following statement: "we are disturbed that a number of Arab Americans and Islamic institutions have been targets of anger and hatred in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks."

In the 1990s, the Anti-Defamation League clashed with the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee in a legal dispute regarding sensitive information the ADL had collected about ADC members' positions on the Arab-Israeli conflict. In 1999, the dispute was finally settled out of court without any finding of wrongdoing. In 2001, the ADL attempted to bar Arab members of CAIR from attending a conference on multicultural inclusion. In 2007 the ADL accused the Council on American-Islamic Relations of having a "poor record on terrorism." CAIR, in turn, accused the ADL of "attempting to muzzle the First Amendment rights of American Muslims by smearing and demonizing them". When the case was settled, Hussein Ibish, director of communications for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), stated that the ADL had gathered data "systematically in a program whose clear intent was to undermine civil rights and Arab-American organizations".

United Kingdom

In Britain, the Greater London Council (GLC) and Labour Committee on Palestine (LCP) have been involved in fighting anti-Arabism through the promotion of Arab and Palestinian rights. The LCP funded a conference on anti-Arab racism in 1989. The National Association of British Arabs also works against discrimination.

United Nations

The outcome document of the Durban Review Conference organized by the UN Human Rights Council, April 21, 2009, Deplores the global rise and number of incidents of racial or religious intolerance and violence, including Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, Christianophobia and anti-Arabism.