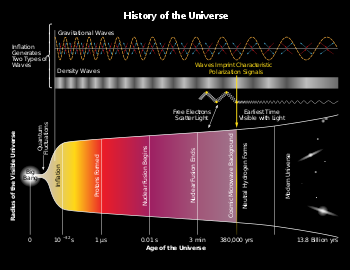

In

physical cosmology,

cosmic inflation,

cosmological inflation, or just

inflation is the exponential

expansion of space in the early

universe. The

inflationary epoch lasted from 10

−36 seconds after the

Big Bang to sometime between 10

−33 and 10

−32 seconds. Following the inflationary period, the Universe continues to expand, but at a less accelerated rate.

[1]

The inflationary hypothesis was developed in the 1980s by physicists

Alan Guth and

Andrei Linde.

[2] It explains the origin of the

large-scale structure of the cosmos.

Quantum fluctuations in the microscopic inflationary region, magnified to cosmic size, become the seeds for the growth of structure in the Universe (see

galaxy formation and evolution and

structure formation).

[3] Many physicists also believe that inflation explains why the Universe appears to be the same in all directions (

isotropic), why the

cosmic microwave background radiation is distributed evenly, why the Universe is flat, and why no

magnetic monopoles have been observed.

While the detailed

particle physics mechanism responsible for inflation is not known, the basic picture makes a number of predictions that have been confirmed by observation.

[4][5] The hypothetical

field thought to be responsible for inflation is called the

inflaton.

[6]

Overview

An expanding universe generally has a

cosmological horizon, which, by analogy with the more familiar

horizon caused by the curvature of the Earth's surface, marks the boundary of the part of the Universe that an observer can see. Light (or other radiation) emitted by objects beyond the cosmological horizon never reaches the observer, because the space in between the observer and the object is expanding too rapidly.

The

observable universe is one

causal patch of a much larger unobservable universe; there are parts of the Universe that cannot communicate with us yet. These parts of the Universe are outside our current cosmological horizon. In the standard hot big bang model, without inflation, the cosmological horizon moves out, bringing new regions into view

[citation needed]. Yet as a local observer sees these regions for the first time, they look no different from any other region of space the local observer has already seen: they have a background radiation that is at nearly exactly the same temperature as the background radiation of other regions, and their space-time curvature is evolving lock-step with ours. This presents a mystery: how did these new regions know what temperature and curvature they were supposed to have? They couldn't have learned it by getting signals, because they were not in communication with our past

light cone before.

[10][11]

Inflation answers this question by postulating that all the regions come from an earlier era with a big vacuum energy, or cosmological constant. A space with a cosmological constant is qualitatively different: instead of moving outward, the cosmological horizon stays put. For any one observer, the distance to the

cosmological horizon is constant. With exponentially expanding space, two nearby observers are separated very quickly; so much so, that the distance between them quickly exceeds the limits of communications. The spatial slices are expanding very fast to cover huge volumes. Things are constantly moving beyond the cosmological horizon, which is a fixed distance away, and everything becomes homogeneous very quickly.

As the inflationary field slowly relaxes to the vacuum, the cosmological constant goes to zero, and space begins to expand normally. The new regions that come into view during the normal expansion phase are exactly the same regions that were pushed out of the horizon during inflation, and so they are necessarily at nearly the same temperature and curvature, because they come from the same little patch of space.

The theory of inflation thus explains why the temperatures and curvatures of different regions are so nearly equal. It also predicts that the total curvature of a space-slice at constant global time is zero. This prediction implies that the total ordinary matter,

dark matter, and residual

vacuum energy in the Universe have to add up to the critical density, and the evidence strongly supports this. More strikingly, inflation allows physicists to calculate the minute differences in temperature of different regions from quantum fluctuations during the inflationary era, and many of these quantitative predictions have been confirmed.

[12][13]

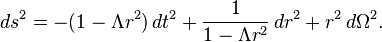

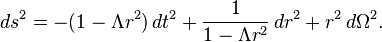

Space expands

To say that space expands exponentially means that two

inertial observers are moving farther apart with accelerating velocity. In stationary coordinates for one observer, a patch of an inflating universe has the following

polar metric:

[14][15]

This is just like an inside-out

black hole metric—it has a zero in the

component on a fixed radius sphere called the

cosmological horizon. Objects are drawn away from the observer at

towards the cosmological horizon, which they cross in a finite proper time. This means that any inhomogeneities are smoothed out, just as any bumps or matter on the surface of a black hole horizon are swallowed and disappear.

Since the

space–time metric has no explicit time dependence, once an observer has crossed the cosmological horizon, observers closer in take its place. This process of falling outward and replacement points closer in are always steadily replacing points further out—an exponential expansion of space–time.

This steady-state exponentially expanding spacetime is called a

de Sitter space, and to sustain it there must be a

cosmological constant, a

vacuum energy proportional to

everywhere. In this case, the

equation of state is

. The physical conditions from one moment to the next are stable: the rate of expansion, called the

Hubble parameter, is nearly constant, and the scale factor of the Universe is proportional to

. Inflation is often called a period of

accelerated expansion because the distance between two fixed observers is increasing exponentially (i.e. at an accelerating rate as they move apart), while

can stay approximately constant (see

deceleration parameter).

Few inhomogeneities remain

Cosmological inflation has the important effect of smoothing out

inhomogeneities,

anisotropies and the

curvature of space. This pushes the Universe into a very simple state, in which it is completely dominated by the inflaton field, the source of the cosmological constant, and the only significant inhomogeneities are the tiny quantum fluctuations in the inflaton. Inflation also dilutes exotic heavy particles, such as the

magnetic monopoles predicted by many extensions to the

Standard Model of

particle physics. If the Universe was only hot enough to form such particles

before a period of inflation, they would not be observed in nature, as they would be so rare that it is quite likely that there are none in the

observable universe. Together, these effects are called the inflationary "no-hair theorem"

[16] by analogy with the

no hair theorem for

black holes.

The "no-hair" theorem works essentially because the cosmological horizon is no different from a black-hole horizon, except for philosophical disagreements about what is on the other side. The interpretation of the no-hair theorem is that the Universe (observable and unobservable) expands by an enormous factor during inflation. In an expanding universe,

energy densities generally fall, or get diluted, as the volume of the Universe increases. For example, the density of ordinary "cold" matter (dust) goes down as the inverse of the volume: when linear dimensions double, the energy density goes down by a factor of eight; the radiation energy density goes down even more rapidly as the Universe expands since the wavelength of each photon is stretched (

redshifted), in addition to the photons being dispersed by the expansion. When linear dimensions are doubled, the energy density in radiation falls by a factor of sixteen (see

the solution of the energy density continuity equation for an ultra-relativistic fluid).

During inflation, the energy density in the inflaton field is roughly constant. However, the energy density in everything else, including inhomogeneities, curvature, anisotropies, exotic particles, and standard-model particles is falling, and through sufficient inflation these all become negligible. This leaves the Universe flat and symmetric, and (apart from the homogeneous inflaton field) mostly empty, at the moment inflation ends and reheating begins.

[17]

Key requirement

A key requirement is that inflation must continue long enough to produce the present observable universe from a single, small inflationary

Hubble volume. This is necessary to ensure that the Universe appears flat, homogeneous and isotropic at the largest observable scales. This requirement is generally thought to be satisfied if the Universe expanded by a factor of at least 10

26 during inflation.

[18]

Reheating

Inflation is a period of

supercooled expansion, when the temperature drops by a factor of 100,000 or so. (The exact drop is model dependent, but in the first models it was typically from 10

27K down to 10

22K.

[19]) This relatively low temperature is maintained during the inflationary phase. When inflation ends the temperature returns to the pre-inflationary temperature; this is called

reheating or thermalization because the large potential energy of the inflaton field decays into particles and fills the Universe with

Standard Model particles, including

electromagnetic radiation, starting the

radiation dominated phase of the Universe. Because the nature of the inflation is not known, this process is still poorly understood, although it is believed to take place through a

parametric resonance.

[20][21]

Motivations

Inflation resolves

several problems in the

Big Bang cosmology that were discovered in the 1970s.

[22] Inflation was first discovered by Guth while investigating the problem of why no

magnetic monopoles are seen today; he found that a positive-energy

false vacuum would, according to

general relativity, generate an exponential expansion of space. It was very quickly realised that such an expansion would resolve many other long-standing problems. These problems arise from the observation that to look like it does

today, the Universe would have to have started from very

finely tuned, or "special" initial conditions at the Big Bang. Inflation attempts to resolve these problems by providing a dynamical mechanism that drives the Universe to this special state, thus making a universe like ours much more likely in the context of the Big Bang theory.

Horizon problem

The

horizon problem is the problem of determining why the Universe appears statistically homogeneous and isotropic in accordance with the

cosmological principle.

[23][24][25] For example, molecules in a canister of gas are distributed homogeneously and isotropically because they are in thermal equilibrium: gas throughout the canister has had enough time to interact to dissipate inhomogeneities and anisotropies. The situation is quite different in the big bang model without inflation, because gravitational expansion does not give the early universe enough time to equilibrate. In a big bang with only the

matter and

radiation known in the

Standard Model, two widely separated regions of the observable universe cannot have equilibrated because they move apart from each other faster than the

speed of light—thus have never come into

causal contact: in the history of the Universe, back to the earliest times, it has not been possible to send a light signal between the two regions. Because they have no interaction, it is difficult to explain why they have the same temperature (are thermally equilibrated). This is because the

Hubble radius in a radiation or matter-dominated universe expands much more quickly than physical lengths and so points that are out of communication are coming into communication. Historically, two proposed solutions were the

Phoenix universe of

Georges Lemaître[26] and the related

oscillatory universe of

Richard Chase Tolman,

[27] and the

Mixmaster universe of

Charles Misner.

[24][28] Lemaître and Tolman proposed that a universe undergoing a number of cycles of contraction and expansion could come into thermal equilibrium. Their models failed, however, because of the buildup of

entropy over several cycles. Misner made the (ultimately incorrect) conjecture that the Mixmaster mechanism, which made the Universe

more chaotic, could lead to statistical homogeneity and isotropy.

Flatness problem

Another problem is the

flatness problem (which is sometimes called one of the

Dicke coincidences, with the other being the

cosmological constant problem).

[29][30] It had been known in the 1960s that the density of matter in the Universe was comparable to the

critical density necessary for a flat universe (that is, a universe whose large scale

geometry is the usual

Euclidean geometry, rather than a

non-Euclidean hyperbolic or

spherical geometry).

[31]:61

Therefore, regardless of the

shape of the universe the contribution of spatial curvature to the expansion of the Universe could not be much greater than the contribution of matter. But as the Universe expands, the curvature

redshifts away more slowly than matter and radiation. Extrapolated into the past, this presents a

fine-tuning problem because the contribution of curvature to the Universe must be exponentially small (sixteen orders of magnitude less than the density of radiation at

big bang nucleosynthesis, for example). This problem is exacerbated by recent observations of the cosmic microwave background that have demonstrated that the Universe is flat to the accuracy of a few percent.

[32]

Magnetic-monopole problem

The

magnetic monopole problem (sometimes called the exotic-relics problem) says that if the early universe were very hot, a large number of very heavy

[why?], stable

magnetic monopoles would be produced. This is a problem with

Grand Unified Theories, which proposes that at high temperatures (such as in the early universe) the

electromagnetic force,

strong, and

weak nuclear forces are not actually fundamental forces but arise due to

spontaneous symmetry breaking from a single

gauge theory.

[33] These theories predict a number of heavy, stable particles that have not yet been observed in nature. The most notorious is the magnetic monopole, a kind of stable, heavy "knot" in the magnetic field.

[34][35] Monopoles are expected to be copiously produced in Grand Unified Theories at high temperature,

[36][37] and they should have persisted to the present day, to such an extent that they would become the primary constituent of the Universe.

[38][39] Not only is that not the case, but all searches for them have failed, placing stringent limits on the density of relic magnetic monopoles in the Universe.

[40] A period of inflation that occurs below the temperature where magnetic monopoles can be produced would offer a possible resolution of this problem: monopoles would be separated from each other as the Universe around them expands, potentially lowering their observed density by many orders of magnitude. Though, as cosmologist

Martin Rees has written, "Skeptics about exotic physics might not be hugely impressed by a theoretical argument to explain the absence of particles that are themselves only hypothetical. Preventive medicine can readily seem 100 percent effective against a disease that doesn't exist!"

[41]

History

Precursors

In the early days of

General Relativity,

Albert Einstein introduced the

cosmological constant to allow a

static solution, which was a three-dimensional sphere with a uniform density of matter. A little later,

Willem de Sitter found a highly symmetric inflating universe, which described a universe with a cosmological constant that is otherwise empty.

[42] It was discovered that Einstein's solution is unstable, and if there are small fluctuations, it eventually either collapses or turns into de Sitter's.

In the early 1970s

Zeldovich noticed the serious flatness and horizon problems of big bang cosmology; before his work, cosmology was presumed to be symmetrical on purely philosophical grounds.

[citation needed] In the Soviet Union, this and other considerations led Belinski and

Khalatnikov to analyze the chaotic

BKL singularity in General Relativity. Misner's

Mixmaster universe attempted to use this chaotic behavior to solve the cosmological problems, with limited success.

In the late 1970s,

Sidney Coleman applied the

instanton techniques developed by

Alexander Polyakov and collaborators to study the fate of the

false vacuum in quantum field theory. Like a metastable phase in statistical mechanics—water below the freezing temperature or above the boiling point—a quantum field would need to nucleate a large enough bubble of the new vacuum, the new phase, in order to make a transition. Coleman found the most likely decay pathway for vacuum decay and calculated the inverse lifetime per unit volume. He eventually noted that gravitational effects would be significant, but he did not calculate these effects and did not apply the results to cosmology.

In the Soviet Union,

Alexei Starobinsky noted that quantum corrections to general relativity should be important in the early universe. These generically lead to curvature-squared corrections to the

Einstein–Hilbert action and a form of

f(R) modified gravity. The solution to Einstein's equations in the presence of curvature squared terms, when the curvatures are large, leads to an effective cosmological constant. Therefore, he proposed that the early universe went through a de Sitter phase, an inflationary era.

[43] This resolved the problems of cosmology, and led to specific predictions for the corrections to the microwave background radiation, corrections that were calculated in detail shortly afterwards.

In 1978, Zeldovich noted the monopole problem, which was an unambiguous quantitative version of the horizon problem, this time in a fashionable subfield of particle physics, which led to several speculative attempts to resolve it. In 1980, working in the west,

Alan Guth realized that false vacuum decay in the early universe would solve the problem, leading him to propose scalar driven inflation. Starobinsky's and Guth's scenarios both predicted an initial deSitter phase, differing only in the details of the mechanism.

Early inflationary models

According to

Andrei Linde, the earliest theory of inflation was proposed by

Erast Gliner (1965) but the theory was not taken seriously except by

Andrei Sakharov, 'who made an attempt to calculate density perturbations produced in this scenario."

[44] Independently, inflation was proposed in January 1980 by

Alan Guth as a mechanism to explain the nonexistence of magnetic monopoles;

[45][46] it was Guth who coined the term "inflation".

[2] At the same time, Starobinsky argued that quantum corrections to gravity would replace the initial singularity of the Universe with an

exponentially expanding deSitter phase.

[47] In October 1980, Demosthenes Kazanas suggested that exponential expansion could eliminate the

particle horizon and perhaps solve the horizon problem,

[48] while Sato suggested that an exponential expansion could eliminate

domain walls (another kind of exotic relic).

[49] In 1981 Einhorn and Sato

[50] published a model similar to Guth's and showed that it would resolve the puzzle of the

magnetic monopole abundance in

Grand Unified Theories. Like Guth, they concluded that such a model not only required fine tuning of the cosmological constant, but also would very likely lead to a much too granular universe, i.e., to large density variations resulting from bubble wall collisions.

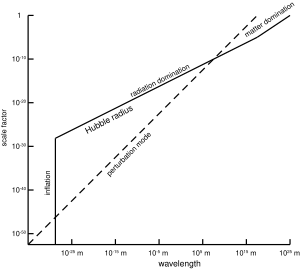

The physical size of the

Hubble radius (solid line) as a function of the linear expansion (scale factor) of the universe. During cosmological inflation, the Hubble radius is constant. The physical wavelength of a perturbation mode (dashed line) is also shown. The plot illustrates how the perturbation mode grows larger than the horizon during cosmological inflation before coming back inside the horizon, which grows rapidly during radiation domination. If cosmological inflation had never happened, and radiation domination continued back until a

gravitational singularity, then the mode would never have been outside the horizon in the very early universe, and no

causal mechanism could have ensured that the universe was homogeneous on the scale of the perturbation mode.

Guth proposed that as the early universe cooled, it was trapped in a

false vacuum with a high energy density, which is much like a

cosmological constant. As the very early universe cooled it was trapped in a

metastable state (it was

supercooled), which it could only decay out of through the process of

bubble nucleation via

quantum tunneling.

Bubbles of

true vacuum spontaneously form in the sea of false vacuum and rapidly begin expanding at the

speed of light. Guth recognized that this model was problematic because the model did not reheat properly: when the bubbles nucleated, they did not generate any radiation. Radiation could only be generated in collisions between bubble walls. But if inflation lasted long enough to solve the initial conditions problems, collisions between bubbles became exceedingly rare. In any one causal patch it is likely that only one bubble will nucleate.

Slow-roll inflation

The bubble collision problem was solved by

Andrei Linde[51] and independently by

Andreas Albrecht and

Paul Steinhardt[52] in a model named

new inflation or

slow-roll inflation (Guth's model then became known as

old inflation). In this model, instead of tunneling out of a false vacuum state, inflation occurred by a

scalar field rolling down a potential energy hill. When the field rolls very slowly compared to the expansion of the Universe, inflation occurs. However, when the hill becomes steeper, inflation ends and reheating can occur.

Effects of asymmetries

Eventually, it was shown that new inflation does not produce a perfectly symmetric universe, but that tiny quantum fluctuations in the inflaton are created. These tiny fluctuations form the primordial seeds for all structure created in the later universe.

[53] These fluctuations were first calculated by

Viatcheslav Mukhanov and G. V. Chibisov in the

Soviet Union in analyzing Starobinsky's similar model.

[54][55][56] In the context of inflation, they were worked out independently of the work of Mukhanov and Chibisov at the three-week 1982 Nuffield Workshop on the Very Early Universe at

Cambridge University.

[57] The fluctuations were calculated by four groups working separately over the course of the workshop:

Stephen Hawking;

[58] Starobinsky;

[59] Guth and So-Young Pi;

[60] and

James M. Bardeen,

Paul Steinhardt and

Michael Turner.

[61]

Observational status

Inflation is a mechanism for realizing the

cosmological principle, which is the basis of the standard model of physical cosmology: it accounts for the homogeneity and isotropy of the observable universe. In addition, it accounts for the observed flatness and absence of magnetic monopoles. Since Guth's early work, each of these observations has received further confirmation, most impressively by the detailed observations of the

cosmic microwave background made by the

Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) spacecraft.

[12] This analysis shows that the Universe is flat to an accuracy of at least a few percent, and that it is homogeneous and isotropic to a part in 100,000.

In addition, inflation predicts that the structures visible in the Universe today formed through the

gravitational collapse of perturbations that were formed as quantum mechanical fluctuations in the inflationary epoch. The detailed form of the spectrum of perturbations called a

nearly-scale-invariant Gaussian random field (or Harrison–Zel'dovich spectrum) is very specific and has only two free parameters, the amplitude of the spectrum and the

spectral index, which measures the slight deviation from scale invariance predicted by inflation (perfect scale invariance corresponds to the idealized de Sitter universe).

[62] Inflation predicts that the observed perturbations should be in

thermal equilibrium with each other (these are called

adiabatic or

isentropic perturbations). This structure for the perturbations has been confirmed by the WMAP spacecraft and other cosmic microwave background experiments,

[12] and

galaxy surveys, especially the ongoing

Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

[63] These experiments have shown that the one part in 100,000 inhomogeneities observed have exactly the form predicted by theory. Moreover, there is evidence for a slight deviation from scale invariance. The

spectral index,

ns is equal to one for a scale-invariant spectrum. The simplest models of inflation predict that this quantity is between 0.92 and 0.98.

[64][65][66][67] From the data taken by the WMAP spacecraft it can be inferred that

ns = 0.963 ± 0.012,

[68] implying that it differs from one at the level of two

standard deviations (2σ). This is considered an important confirmation of the theory of inflation.

[12]

A number of theories of inflation have been proposed that make radically different predictions, but they generally have much more

fine tuning than is necessary.

[64][65] As a physical model, however, inflation is most valuable in that it robustly predicts the initial conditions of the Universe based on only two adjustable parameters: the spectral index (that can only change in a small range) and the amplitude of the perturbations. Except in contrived models, this is true regardless of how inflation is realized in particle physics.

Occasionally, effects are observed that appear to contradict the simplest models of inflation. The first-year WMAP data suggested that the spectrum might not be nearly scale-invariant, but might instead have a slight curvature.

[69] However, the third-year data revealed that the effect was a statistical anomaly.

[12] Another effect has been remarked upon since the first cosmic microwave background satellite, the

Cosmic Background Explorer: the amplitude of the

quadrupole moment of the cosmic microwave background is unexpectedly low and the other low multipoles appear to be preferentially aligned with the

ecliptic plane. Some have claimed that this is a signature of non-Gaussianity and thus contradicts the simplest models of inflation. Others have suggested that the effect may be due to other new physics, foreground contamination, or even

publication bias.

[70]

An experimental program is underway to further test inflation with more precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background. In particular, high precision measurements of the so-called "B-modes" of the

polarization of the background radiation could provide evidence of the

gravitational radiation produced by inflation, and could also show whether the energy scale of inflation predicted by the simplest models (10

15–10

16 GeV) is correct.

[65][66]

In March 2014, it was announced that B-mode polarization of the background radiation consistent with that predicted from inflation had been demonstrated by a South Pole experiment, a collaboration led by four principal investigators from the California Institute of Technology, Harvard University, Stanford University, and the University of Minnesota

BICEP2.

[7][8][9][71][72][73] However, on 19 June 2014, lowered confidence in confirming the findings was reported;

[72][74][75] on 19 September 2014, a further reduction in confidence was reported

[76][77] and, on 30 January 2015, even less confidence yet was reported.

[78][79]

Other potentially corroborating measurements are expected to be performed by the

Planck spacecraft, although it is unclear if the signal will be visible, or if contamination from foreground sources will interfere with these measurements.

[80] Other forthcoming measurements, such as those of

21 centimeter radiation (radiation emitted and absorbed from neutral hydrogen before the

first stars turned on), may measure the power spectrum with even greater resolution than the cosmic microwave background and galaxy surveys, although it is not known if these measurements will be possible or if interference with

radio sources on Earth and in the galaxy will be too great.

[81]

Dark energy is broadly similar to inflation, and is thought to be causing the expansion of the present-day universe to accelerate. However, the energy scale of dark energy is much lower, 10

−12 GeV, roughly 27

orders of magnitude less than the scale of inflation.

Theoretical status

In the early proposal of Guth, it was thought that the inflaton was the

Higgs field, the field that explains the mass of the elementary particles.

[46] It is now believed by some that the inflaton cannot be the Higgs field

[82] although the recent discovery of the Higgs boson has increased the number of works considering the Higgs field as inflaton.

[83] One problem of this identification is the current tension with experimental data at the electroweak scale,

[84] which is currently under study at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Other models of inflation relied on the properties of grand unified theories.

[52] Since the simplest models of

grand unification have failed, it is now thought by many physicists that inflation will be included in a

supersymmetric theory like

string theory or a supersymmetric grand unified theory. At present, while inflation is understood principally by its detailed predictions of the

initial conditions for the hot early universe, the particle physics is largely

ad hoc modelling. As such, though predictions of inflation have been consistent with the results of observational tests, there are many open questions about the theory.

Fine-tuning problem

One of the most severe challenges for inflation arises from the need for

fine tuning in inflationary theories. In new inflation, the

slow-roll conditions must be satisfied for inflation to occur. The slow-roll conditions say that the inflaton

potential must be flat (compared to the large

vacuum energy) and that the inflaton particles must have a small mass

[clarification needed].

[85] In order for the new inflation theory of Linde, Albrecht and Steinhardt to be successful, therefore, it seemed that the Universe must have a scalar field with an especially flat potential and special initial conditions. However, there are ways to explain these fine-tunings. For example, classically scale invariant field theories, where scale invariance is broken by quantum effects, provide an explanation of the flatness of inflationary potentials, as long as the theory can be studied through perturbation theory.

[86]

Andrei Linde

Andrei Linde proposed a theory known as

chaotic inflation in which he suggested that the conditions for inflation are actually satisfied quite generically and inflation will occur in virtually

any universe that begins in a chaotic, high energy state and has a scalar field with unbounded potential energy.

[87] However, in his model the inflaton field necessarily takes values larger than one

Planck unit: for this reason, these are often called

large field models and the competing new inflation models are called

small field models. In this situation, the predictions of

effective field theory are thought to be invalid, as

renormalization should cause large corrections that could prevent inflation.

[88]

This problem has not yet been resolved and some cosmologists argue that the small field models, in which inflation can occur at a much lower energy scale, are better models of inflation.

[89] While inflation depends on quantum field theory (and the

semiclassical approximation to

quantum gravity) in an important way, it has not been completely reconciled with these theories.

Robert Brandenberger has commented on fine-tuning in another situation.

[90] The amplitude of the primordial inhomogeneities produced in inflation is directly tied to the energy scale of inflation. There are strong suggestions that this scale is around 10

16 GeV or 10

−3 times the

Planck energy. The natural scale is naïvely the Planck scale so this small value could be seen as another form of fine-tuning (called a

hierarchy problem): the energy density given by the scalar potential is down by 10

−12 compared to the

Planck density. This is not usually considered to be a critical problem, however, because the scale of inflation corresponds naturally to the scale of gauge unification.

Eternal inflation

In many models of inflation, the inflationary phase of the Universe's expansion lasts forever in at least some regions of the Universe. This occurs because inflating regions expand very rapidly, reproducing themselves. Unless the rate of decay to the non-inflating phase is sufficiently fast, new inflating regions are produced more rapidly than non-inflating regions. In such models most of the volume of the Universe at any given time is inflating. All models of eternal inflation produce an infinite multiverse, typically a fractal.

Although new inflation is classically rolling down the potential, quantum fluctuations can sometimes bring it back up to previous levels. These regions in which the inflaton fluctuates upwards expand much faster than regions in which the inflaton has a lower potential energy, and tend to dominate in terms of physical volume. This steady state, which first developed by Vilenkin,

[91] is called "eternal inflation". It has been shown that any inflationary theory with an unbounded potential is eternal.

[92][not in citation given] It is a popular conclusion among physicists that this steady state cannot continue forever into the past.

[93][94][95] The inflationary spacetime, which is similar to

de Sitter space, is incomplete without a contracting region. However, unlike de Sitter space, fluctuations in a contracting inflationary space will collapse to form a

gravitational singularity, a point where densities become infinite.

Therefore, it is necessary to have a theory for the Universe's initial conditions. Linde, however, believes inflation may be past eternal.

[96]

In eternal inflation, regions with inflation have an exponentially growing volume, while regions that are not inflating don't. This suggests that the volume of the inflating part of the Universe in the global picture is always unimaginably larger than the part that has stopped inflating, even though inflation eventually ends as seen by any single pre-inflationary observer. Scientists disagree about how to assign a probability distribution to this hypothetical

anthropic landscape. If the probability of different regions is counted by volume, one should expect that inflation will never end, or applying boundary conditions that a local observer exists to observe it, that inflation will end as late as possible. Some physicists believe this paradox can be resolved by weighting observers by their pre-inflationary volume.

Initial conditions

Some physicists have tried to avoid the initial conditions problem by proposing models for an eternally inflating universe with no origin.

[97][98][99][100] These models propose that while the Universe, on the largest scales, expands exponentially it was, is and always will be, spatially infinite and has existed, and will exist, forever.

Other proposals attempt to describe the ex nihilo creation of the Universe based on

quantum cosmology and the following inflation. Vilenkin put forth one such scenario.

[91] Hartle and Hawking offered the

no-boundary proposal for the initial creation of the Universe in which inflation comes about naturally.

[101]

Alan Guth has described the inflationary universe as the "ultimate free lunch":

[102][103] new universes, similar to our own, are continually produced in a vast inflating background. Gravitational interactions, in this case, circumvent (but do not violate) the

first law of thermodynamics (

energy conservation) and the

second law of thermodynamics (

entropy and the

arrow of time problem). However, while there is consensus that this solves the initial conditions problem, some have disputed this, as it is much more likely that the Universe came about by a

quantum fluctuation.

Donald Page was an outspoken critic of inflation because of this anomaly.

[104] He stressed that the thermodynamic

arrow of time necessitates low

entropy initial conditions, which would be highly unlikely. According to them, rather than solving this problem, the inflation theory further aggravates it – the reheating at the end of the inflation era increases entropy, making it necessary for the initial state of the Universe to be even more orderly than in other Big Bang theories with no inflation phase.

Hawking and Page later found ambiguous results when they attempted to compute the probability of inflation in the Hartle-Hawking initial state.

[105] Other authors have argued that, since inflation is eternal, the probability doesn't matter as long as it is not precisely zero: once it starts, inflation perpetuates itself and quickly dominates the Universe.

[106][107]:223–225 However, Albrecht and Lorenzo Sorbo have argued that the probability of an inflationary cosmos, consistent with today's observations, emerging by a random fluctuation from some pre-existent state,

compared with a non-inflationary cosmos overwhelmingly favours the inflationary scenario, simply because the "seed" amount of non-gravitational energy required for the inflationary cosmos is so much less than any required for a non-inflationary alternative, which outweighs any entropic considerations.

[108]

Another problem that has occasionally been mentioned is the trans-Planckian problem or trans-Planckian effects.

[109] Since the energy scale of inflation and the Planck scale are relatively close, some of the quantum fluctuations that have made up the structure in our universe were smaller than the Planck length before inflation. Therefore, there ought to be corrections from Planck-scale physics, in particular the unknown quantum theory of gravity. There has been some disagreement about the magnitude of this effect: about whether it is just on the threshold of detectability or completely undetectable.

[110]

Hybrid inflation

Another kind of inflation, called

hybrid inflation, is an extension of new inflation. It introduces additional scalar fields, so that while one of the scalar fields is responsible for normal slow roll inflation, another triggers the end of inflation: when inflation has continued for sufficiently long, it becomes favorable to the second field to decay into a much lower energy state.

[111]

In hybrid inflation, one of the scalar fields is responsible for most of the energy density (thus determining the rate of expansion), while the other is responsible for the slow roll (thus determining the period of inflation and its termination). Thus fluctuations in the former inflaton would not affect inflation termination, while fluctuations in the latter would not affect the rate of expansion. Therefore hybrid inflation is not eternal.

[112][113] When the second (slow-rolling) inflaton reaches the bottom of its potential, it changes the location of the minimum of the first inflaton's potential, which leads to a fast roll of the inflaton down its potential, leading to termination of inflation.

Inflation and string cosmology

The discovery of

flux compactifications have opened the way for reconciling inflation and string theory.

[114] A new theory, called

brane inflation suggests that inflation arises from the motion of

D-branes[115] in the compactified geometry, usually towards a stack of anti-D-branes. This theory, governed by the

Dirac-Born-Infeld action, is very different from ordinary inflation. The dynamics are not completely understood. It appears that special conditions are necessary since inflation occurs in tunneling between two vacua in the

string landscape. The process of tunneling between two vacua is a form of old inflation, but new inflation must then occur by some other mechanism.

Inflation and loop quantum gravity

When investigating the effects the theory of

loop quantum gravity would have on cosmology, a

loop quantum cosmology model has evolved that provides a possible mechanism for cosmological inflation. Loop quantum gravity assumes a quantized spacetime. If the energy density is larger than can be held by the quantized spacetime, it is thought to bounce back.

Inflation and generalized uncertainty principle (GUP)

The effects of generalized uncertainty principle (GUP) on the inflationary dynamics and the thermodynamics of the

early Universe are studied.

[116] Using the GUP approach,

Tawfik et al. evaluated the tensorial and scalar density fluctuations in the inflation era and compared them with the standard case. They found a good agreement with the

Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data. Assuming that a quantum gas of scalar particles is confined within a thin layer near the apparent horizon of the

Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker Universe that satisfies the boundary condition,

Tawfik et al. calculated the number and entropy densities and the free energy arising from the quantum states using the GUP approach. Furthermore, a qualitative estimation for effects of the quantum gravity on all these thermodynamic quantities was introduced.

Alternatives to inflation

The flatness and horizon problems are naturally solved in the

Einstein-Cartan-Sciama-Kibble theory of gravity, without needing an exotic form of matter and introducing free parameters.

[117][118] This theory extends general relativity by removing a constraint of the symmetry of the affine connection and regarding its antisymmetric part, the

torsion tensor, as a dynamical variable. The minimal coupling between torsion and Dirac spinors generates a spin-spin interaction that is significant in fermionic matter at extremely high densities. Such an interaction averts the unphysical Big Bang singularity, replacing it with a cusp-like bounce at a finite minimum scale factor, before which the Universe was contracting. The rapid expansion immediately after the

Big Bounce explains why the present Universe at largest scales appears spatially flat, homogeneous and isotropic. As the density of the Universe decreases, the effects of torsion weaken and the Universe smoothly enters the radiation-dominated era.

There are models that explain some of the observations explained by inflation. However none of these "alternatives" has the same breadth of explanation as inflation, and still require inflation for a more complete fit with observation; they should therefore be regarded as adjuncts to inflation, rather than as alternatives.

String theory requires that, in addition to the three observable spatial dimensions, there exist additional dimensions that are curled up or

compactified (see also

Kaluza–Klein theory). Extra dimensions appear as a frequent component of

supergravity models and other approaches to

quantum gravity. This raised the contingent question of why four space-time dimensions became large and the rest became unobservably small. An attempt to address this question, called

string gas cosmology, was proposed by

Robert Brandenberger and

Cumrun Vafa.

[119] This model focuses on the dynamics of the early universe considered as a hot gas of strings. Brandenberger and Vafa show that a dimension of

spacetime can only expand if the strings that wind around it can efficiently annihilate each other. Each string is a one-dimensional object, and the largest number of dimensions in which two strings will

generically intersect (and, presumably, annihilate) is three. Therefore, one argues that the most likely number of non-compact (large) spatial dimensions is three. Current work on this model centers on whether it can succeed in stabilizing the size of the compactified dimensions and produce the correct spectrum of primordial density perturbations. For a recent review, see

[120] The authors admits that their model "does not solve the entropy and flatness problems of standard cosmology ..... and we can provide no explanation for why the current universe is so close to being spatially flat".

[121]

The

ekpyrotic and

cyclic models are also considered adjuncts to inflation. These models solve the

horizon problem through an expanding epoch well

before the Big Bang, and then generate the required spectrum of primordial density perturbations during a contracting phase leading to a

Big Crunch. The Universe passes through the Big Crunch and emerges in a hot

Big Bang phase. In this sense they are reminiscent of the

oscillatory universe proposed by

Richard Chace Tolman: however in Tolman's model the total age of the Universe is necessarily finite, while in these models this is not necessarily so. Whether the correct spectrum of density fluctuations can be produced, and whether the Universe can successfully navigate the Big Bang/Big Crunch transition, remains a topic of controversy and current research. Ekpyrotic models avoid the

magnetic monopole problem as long as the temperature at the Big Crunch/Big Bang transition remains below the Grand Unified Scale, as this is the temperature required to produce magnetic monopoles in the first place. As things stand, there is no evidence of any 'slowing down' of the expansion, but this is not surprising as each cycle is expected to last on the order of a trillion years.

Another adjunct, the

varying speed of light model has also been theorized by

Jean-Pierre Petit in 1988,

John Moffat in 1992 as well

Andreas Albrecht and

João Magueijo in 1999, instead of superluminal expansion the speed of light was 60 orders of magnitude faster than its current value solving the horizon and homogeneity problems in the early universe.

Criticisms

Since its introduction by Alan Guth in 1980, the inflationary paradigm has become widely accepted. Nevertheless, many physicists, mathematicians, and philosophers of science have voiced criticisms, claiming untestable predictions and a lack of serious empirical support.

[106] In 1999, John Earman and Jesús Mosterín published a thorough critical review of inflationary cosmology, concluding, "we do not think that there are, as yet, good grounds for admitting any of the models of inflation into the standard core of cosmology."

[122]

In order to work, and as pointed out by

Roger Penrose from 1986 on, inflation requires extremely specific initial conditions of its own, so that the problem (or pseudo-problem) of initial conditions is not solved: "There is something fundamentally misconceived about trying to explain the uniformity of the early universe as resulting from a thermalization process. [...] For, if the thermalization is actually doing anything [...] then it represents a definite increasing of the entropy. Thus, the universe would have been even more special before the thermalization than after."

[123] The problem of specific or "fine-tuned" initial conditions would not have been solved; it would have gotten worse.

A recurrent criticism of inflation is that the invoked inflation field does not correspond to any known physical field, and that its

potential energy curve seems to be an ad hoc contrivance to accommodate almost any data obtainable.

Paul J. Steinhardt, one of the founding fathers of inflationary cosmology, has recently become one of its sharpest critics. He calls 'bad inflation' a period of accelerated expansion whose outcome conflicts with observations, and 'good inflation' one compatible with them: "Not only is bad inflation more likely than good inflation, but no inflation is more likely than either.... Roger Penrose considered all the possible configurations of the inflaton and gravitational fields. Some of these configurations lead to inflation ... Other configurations lead to a uniform, flat universe directly – without inflation. Obtaining a flat universe is unlikely overall. Penrose's shocking conclusion, though, was that obtaining a flat universe without inflation is much more likely than with inflation – by a factor of 10 to the googol (10 to the 100) power!"

[106][107]

component on a fixed radius sphere called the

component on a fixed radius sphere called the  towards the cosmological horizon, which they cross in a finite proper time. This means that any inhomogeneities are smoothed out, just as any bumps or matter on the surface of a black hole horizon are swallowed and disappear.

towards the cosmological horizon, which they cross in a finite proper time. This means that any inhomogeneities are smoothed out, just as any bumps or matter on the surface of a black hole horizon are swallowed and disappear. everywhere. In this case, the

everywhere. In this case, the  . The physical conditions from one moment to the next are stable: the rate of expansion, called the

. The physical conditions from one moment to the next are stable: the rate of expansion, called the  . Inflation is often called a period of accelerated expansion because the distance between two fixed observers is increasing exponentially (i.e. at an accelerating rate as they move apart), while

. Inflation is often called a period of accelerated expansion because the distance between two fixed observers is increasing exponentially (i.e. at an accelerating rate as they move apart), while