From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

1918 flu pandemic (January 1918 – December 1920) was an unusually deadly

influenza pandemic, the first of the two pandemics Involving

H1N1 influenza virus.

[1] It infected 500 million people around the world,

including remote Pacific islands and the Arctic, and resulted in the

deaths of 50 to 100 million (three to five percent of the world's

population

[3]), making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history. Disease had already greatly limited

life expectancy

in the early 20th century. A considerable spike occurred at the time of

the pandemic, specifically the year 1918. Life expectancy in the United

States alone dropped by about 12 years.

[7][8][9][10]

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill juvenile, elderly,

or already weakened patients; in contrast, the 1918 pandemic

predominantly killed previously healthy young adults.

There are several possible explanations for the high mortality rate

of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Some research suggests that the specific

variant of the virus had an unusually aggressive nature. One group of

researchers recovered the original virus from the bodies of frozen

victims, and found that transfection in animals caused a rapid

progressive respiratory failure and death through a

cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's

immune system).

It was then postulated that the strong immune reactions of young adults

ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune systems of children and

middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths among those groups.

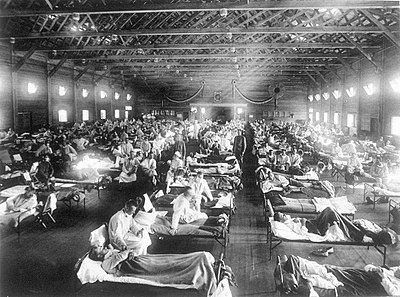

More recent investigations, mainly based on original medical reports from the period of the pandemic,

[12][13]

found that the viral infection itself was not more aggressive than any

previous influenza, but that the special circumstances (malnourishment,

overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, poor hygiene) promoted

bacterial superinfection that killed most of the victims typically after

a somewhat prolonged death bed.

[14][15]

Historical and

epidemiological data are inadequate to identify the pandemic's geographic origin. It was implicated in the outbreak of

encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.

To maintain morale,

wartime censors minimized early reports of illness and mortality in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and the United States.

[18] However, papers were free to report the epidemic's effects in neutral Spain (such as the grave illness of

King Alfonso XIII). This reporting dichotomy created a false impression of Spain as especially hard hit, thereby giving rise to the pandemic's nickname,

Spanish Flu. In Spain, a different nickname was adopted, the Naples Soldier (

Soldado de Nápoles), which came from a musical operetta (zarzuela) titled

La canción del olvido (

The Song of Forgetting), which premiered in Madrid during the first epidemic wave.

Federico Romero, one of the librettists, quipped that the play's most popular musical number,

Naples Soldier, was as catchy as the flu.

History

Hypotheses about source

The site of the very first confirmed outbreak was at Camp Funston,

Fort Riley,

Kansas,

then a military training facility preparing American troops for

involvement in World War I. The first victim diagnosed with the new

strain of flu on Monday, March 11, 1918, was mess cook Private Albert

Gitchell.

[23][24] Historian

Alfred W. Crosby recorded that the flu originated in Kansas, and popular writer

John Barry echoed Crosby in describing

Haskell County, Kansas, as the point of origin.

In contrast, investigative work in 1999 by a British team led by

virologist John Oxford[27] of

St Bartholomew's Hospital and the

Royal London Hospital identified the major troop staging and hospital camp in

Étaples,

France, as being the center of the 1918 flu pandemic. These researchers

postulated that a significant precursor virus, harbored in birds,

mutated to pigs that were kept near the front.

[28]

Earlier hypotheses of the epidemic's origin have varied. Some hypothesized the flu originated in East Asia.

[29][30] Dr. C. Hannoun, leading expert of the 1918 flu for the

Institut Pasteur, asserted the former virus was likely to have come from China, mutating in the United States near

Boston and spreading to

Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, Europe, and the world using Allied soldiers and sailors as main spreaders.

[31] He considered several other hypotheses of origin, such as Spain,

Kansas, and Brest, as being possible, but not likely.

Political scientist

Andrew Price-Smith published data from the

Austrian archives suggesting the influenza had earlier origins, beginning in

Austria in the spring of 1917.

In 2014, historian Mark Humphries of Canada's

Memorial University of Newfoundland stated that newly unearthed records confirmed that one of the side stories of the war, the mobilization of 96,000

Chinese laborers

to work behind the British and French lines on World War I's western

front, might have been the source of the pandemic. In the report,

Humphries found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck

northern China in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese

health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.

[34] However, a report published in 2016 in the Journal of the

Chinese Medical Association

found no evidence that the 1918 virus was imported to Europe from

Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers. In fact, it found

evidence that the virus had been circulating in the European armies for

months and potentially years before the 1918 pandemic.

[35]

Spread

When an infected person sneezes or coughs, more than half a million virus particles can be spread to those close by.

[36] The close quarters and massive troop movements of

World War I

hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and

augmented mutation; the war may also have increased the lethality of the

virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by

malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks,

increasing their susceptibility.

A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of this flu was increased

travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers,

sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease.

[38]

In the United States, the disease was first observed in

Haskell County, Kansas,

in January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the U.S.

Public Health Service's academic journal. On 4 March 1918, company cook

Albert Gitchell reported sick at

Fort Riley, Kansas. By noon on 11 March 1918, over 100 soldiers were in the hospital.

[39] Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick.

[40] By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached

Queens, New York.

[41] Failure to take preventative measures in March/April was later criticised.

In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in

Brest, France; in

Freetown, Sierra Leone; and in the U.S. in

Boston, Massachusetts. The Spanish flu also spread through Ireland, carried there by returning Irish soldiers. The

Allies of World War I

came to call it the Spanish flu, primarily because the pandemic

received greater press attention after it moved from France to Spain in

November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed

wartime

censorship.

[42]

Mortality

Around the globe

The difference between the influenza mortality age-distributions of the

1918 epidemic and normal epidemics – deaths per 100,000 persons in each

age group, United States, for the interpandemic years 1911–1917 (dashed

line) and the pandemic year 1918 (solid line)

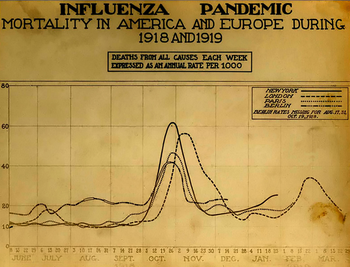

Three pandemic waves: weekly combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, United Kingdom, 1918–1919

The global

mortality rate

from the 1918/1919 pandemic is not known, but an estimated 10% to 20%

of those who were infected died. With about a third of the world

population infected, this

case-fatality ratio means 3% to 6% of the entire global population died.

Influenza may have killed as many as 25 million people in its first 25

weeks. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people, while current estimates say 50–100 million people worldwide were killed.

This

pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed more people than the

Black Death.

It is said that this flu killed more people in 24 weeks than AIDS

killed in 24 years, and more in a year than the Black Death killed in a

century.

The disease killed in every corner of the globe. As many as 17 million died in

India, about 5% of the population.

[47] The death toll in

India's British-ruled districts alone was 13.88 million.

[48]

In Japan, of the 23 million people who were affected, 390,000 died.

[49] In the

Dutch East Indies (now

Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died among 30 million inhabitants.

[50] In

Tahiti 13% of the population died during only a month. Similarly, in

Samoa 22% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.

In the U.S., about 28% of the population became infected, and 500,000 to 675,000 died.

[52] Native American tribes were particularly hard hit. In the

Four Corners area alone, 3,293 deaths were registered among Native Americans.

[53] Entire village communities perished in

Alaska.

[54] In Canada 50,000 died.

[55] In Brazil 300,000 died, including president

Rodrigues Alves.

[56] In Britain, as many as 250,000 died; in France, more than 400,000.

[57] In West Africa an influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people in

Ghana. Tafari Makonnen (the future

Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia) was one of the first

Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived,

[59] although many of his family's subjects did not; estimates for the fatalities in the capital city,

Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher. In

British Somaliland one official estimated that 7% of the native population died.

This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate

of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be

caused by

cytokine storms. Symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as

dengue,

cholera, or

typhoid.

One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was

hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and

intestine. Bleeding from the ears and

petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred". The majority of deaths were from

bacterial pneumonia,

[63] a common

secondary infection associated with influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, by causing massive

hemorrhages and

edema in the lung.

The unusually severe disease killed up to 20% of those infected, as opposed to the usual flu epidemic

mortality rate of 0.1%.

Patterns of fatality

An unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young

adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of pandemic influenza deaths in the US

occurred in people under 65, and nearly half in young adults 20 to

40 years old. In 1920 the mortality rate among people under 65 had

decreased six-fold to half the mortality rate of people over 65, but

still 92% of deaths occurred in people under 65. This is noteworthy, since influenza is normally most deadly to weak individuals, such as

infants (under age two), the very old (over age 70), and the

immunocompromised. In 1918, older adults may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the

1889–1890 flu pandemic, known as the Russian flu.

[66] According to historian John M. Barry, the most vulnerable of all –

"those most likely, of the most likely", to die – were pregnant women.

He reported that in thirteen studies of hospitalized women in the

pandemic, the death rate ranged from 23% to 71%.

[67] Of the pregnant women who survived childbirth, over one-quarter (26%) lost the child.

Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the

Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.

[69]

Modern analysis has shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a

cytokine storm, which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults.

In fast-progressing cases, mortality was primarily from

pneumonia, by virus-induced pulmonary

consolidation. Slower-progressing cases featured secondary bacterial pneumonias, and there may have been

neural involvement that led to

mental disorders in some cases. Some deaths resulted from malnourishment.

A study – conducted by He et al. – used a mechanistic modelling

approach to study the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. They

tried to study the factors that underlie variability in temporal

patterns, and the patterns of mortality and morbidity. Their analysis

suggests that temporal variations in transmission rate provide the best

explanation and the variation in transmission required to generate these

three waves is within biologically plausible values.

Another study by He et al. used a simple epidemic model, to

incorporate three factors including: school opening and closing,

temperature changes over the course of the outbreak, and human

behavioral changes in response to the outbreak to infer the cause of the

three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Their modelling results

showed that all three factors are important but human behavioral

responses showed the largest effects.

Deadly second wave

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much deadlier than the

first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at

risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people

recovered easily. But in August, when the second wave began in France,

Sierra Leone and the United States,

[72] the virus had

mutated to a much deadlier form.

This increased severity has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War.

In civilian life, natural selection favours a mild strain. Those who

get very ill stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives,

preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, natural

selection was reversed. Soldiers with a mild strain stayed where they

were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded

field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. The second wave began and

the flu quickly spread around the world again. Consequently, during

modern pandemics health officials pay attention when the virus reaches

places with social upheaval (looking for deadlier strains of the virus).

The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections were now

immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu. This was most dramatically illustrated in

Copenhagen,

which escaped with a combined mortality rate of just 0.29% (0.02% in

the first wave and 0.27% in the second wave) because of exposure to the

less-lethal first wave.

[75]

On the rest of the population it was far more deadly now; the most

vulnerable people were those like the soldiers in the trenches – young

previously healthy adults.

Devastated communities

A chart of deaths in major cities, showing a peak in the autumn of 1918.

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many were incapacitated

that much of everyday life was hampered. Some communities closed all

stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There were reports

that the health-care workers could not tend the sick nor the

gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were

dug by

steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.

[77]

Several

Pacific island

territories were particularly hard-hit. The pandemic reached them from

New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent

ships carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand, the flu reached

Tonga (killing 8% of the population),

Nauru (16%) and

Fiji (5%, 9,000 people).

Worst affected was

German Samoa, today the independent state of

Samoa, which had been

occupied by New Zealand

in 1914. A crippling 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult

men, 22% of adult women and 10% of children died. By contrast, the flu

was kept away from

American Samoa when

Governor John Martin Poyer imposed a blockade.

In New Zealand itself, 8,573 deaths were attributed to the 1918

pandemic influenza, resulting in a total population fatality rate of

0.74%.

In Ireland, the Spanish Flu accounted for 10% of the total deaths in

1918 which can be seen as quite detrimental considering World War 1 was

still occurring.

Less-affected areas

In Japan, 257,363 deaths were attributed to influenza by July 1919,

giving an estimated 0.425% mortality rate, much lower than nearly all

other Asian countries for which data are available. The Japanese

government severely restricted maritime travel to and from the home

islands when the pandemic struck.

In the Pacific,

American Samoa[80] and the French colony of

New Caledonia[81] also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective

quarantines. In Australia, nearly 12,000 perished.

[82]

By the end of the pandemic, the isolated island of

Marajó, in Brazil's Amazon River Delta had not reported an outbreak.

[83]

Aspirin poisoning

In a 2009 paper published in the journal

Clinical Infectious Diseases, Karen Starko proposed that

aspirin poisoning

had contributed substantially to the fatalities. She based this on the

reported symptoms in those dying from the flu, as reported in the post

mortem reports still available, and also the timing of the big "death

spike" in October 1918 which happened right after the

Surgeon General of the United States Army, and the

Journal of the American Medical Association both recommended very large doses of 8.0–31.2 g of aspirin per day. Starko also suggests that the wave of aspirin poisonings was due to a "

perfect storm" of events:

Bayer's

patent on aspirin expired, so that many companies rushed in to make a

profit and greatly increased the supply; this coincided with the flu

pandemic; and the symptoms of aspirin poisoning were not known at the

time.

As an explanation for the

universally high mortality rate,

this hypothesis was questioned in a letter to the journal published in

April 2010 by Andrew Noymer and Daisy Carreon of the

University of California, Irvine, and Niall Johnson of the

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

They questioned this universal applicability given the high mortality

rate in countries such as India, where there was little or no access to

aspirin at the time. They concluded that "the

salicylate

[aspirin] poisoning hypothesis [was] difficult to sustain as the

primary explanation for the unusual virulence of the 1918–1919 influenza

pandemic".

But they overlooked that inexpensive aspirin had become available in

India and other places after October 1918, when the Bayer patent

expired. In responding, Starko pointed to anecdotal evidence of aspirin

over-prescription in India and argued that even if aspirin

over-prescription had not contributed to the high Indian mortality rate,

it could still have been a major factor for other high rates in areas

where other exacerbating factors present in India played less of a role.

End of the pandemic

After the lethal second wave struck in late 1918, new cases dropped

abruptly – almost to nothing after the peak in the second wave.

In Philadelphia, for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending 16

October, but by 11 November, influenza had almost disappeared from the

city. One explanation for the rapid decline of the lethality of the

disease is that doctors simply got better at preventing and treating the

pneumonia that developed after the victims had contracted the virus,

although John Barry stated in his book that researchers have found no

evidence to support this.

Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to

a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza

viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less

lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out (see also

"Deadly Second Wave", above).

Legacy

Academic

Andrew Price-Smith

has made the argument that the virus helped tip the balance of power in

the later days of the war towards the Allied cause. He provides data

that the viral waves hit the Central Powers before they hit the Allied

powers, and that both

morbidity and

mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.

In the United States, Britain and other countries, despite the

relatively high morbidity and mortality rates that resulted from the

epidemic in 1918–1919, the Spanish flu began to fade from public

awareness over the decades until the arrival of news about

bird flu and other pandemics in the 1990s and 2000s. This has led some historians to label the Spanish flu a "forgotten pandemic".

Various theories of why the Spanish flu was "forgotten" include the

rapid pace of the pandemic, which killed most of its victims in the

United States, for example, within a period of less than nine months,

resulting in limited media coverage. The general population was familiar

with patterns of pandemic disease in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries:

typhoid,

yellow fever,

diphtheria, and

cholera all occurred near the same time. These outbreaks probably lessened the significance of the influenza pandemic for the public. In some areas, the flu was not reported on, the only mention being that of advertisements for medicines claiming to cure it.

In addition, the outbreak coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War.

Another explanation involves the age group affected by the disease. The

majority of fatalities, from both the war and the epidemic, were among

young adults. The deaths caused by the flu may have been overlooked due

to the large numbers of deaths of young men in the war or as a result of

injuries. When people read the obituaries, they saw the war or postwar

deaths and the deaths from the influenza side by side. Particularly in

Europe, where the war's toll was extremely high, the flu may not have

had a great, separate, psychological impact, or may have seemed a mere

extension of the war's tragedies.

The duration of the pandemic and the war could have also played a

role. The disease would usually only affect a certain area for a month

before leaving, while the war, which most had initially expected to end

quickly, had lasted for four years by the time the pandemic struck. This

left little time for the disease to have a significant impact on the

economy.

Regarding global economic effects, many businesses in the

entertainment and service industries suffered losses in revenue, while

the health care industry reported profit gains.

Historian Nancy Bristow has argued that the pandemic, when combined

with the increasing number of women attending college, contributed to

the success of women in the field of nursing. This was due in part to

the failure of medical doctors, who were predominantly men, to contain

and prevent the illness. Nursing staff, who were predominantly women,

felt more inclined to celebrate the success of their patient care and

less inclined to identify the spread of the disease with their own work.

[92]

In Spain, sources from the period explicitly linked the Spanish flu to the cultural figure of

Don Juan. The nickname for the flu, the "Naples Soldier", was adopted from Federico Romero and

Guillermo Fernández Shaw's operetta,

The Song of Forgetting (

La canción del olvido),

the protagonist of which is a stock Don Juan type. Davis has argued the

Spanish flu–Don Juan connection served a cognitive function, allowing

Spaniards to make sense of their epidemic experience by interpreting it

through a familiar template, namely the Don Juan story.

Spanish flu research

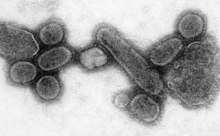

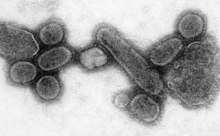

An electron micrograph showing recreated 1918 influenza virions.

The origin of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the relationship between

the near-simultaneous outbreaks in humans and swine, have been

controversial. One hypothesis is that the virus strain originated at

Fort Riley,

Kansas,

in viruses in poultry and swine which the fort bred for food; the

soldiers were then sent from Fort Riley around the world, where they

spread the disease.

[94]

Similarities between a reconstruction of the virus and avian viruses,

combined with the human pandemic preceding the first reports of

influenza in swine, led researchers to conclude the influenza virus

jumped directly from birds to humans, and swine caught the disease from

humans.

[95]

Others have disagreed, and more recent research has suggested the strain may have originated in a nonhuman, mammalian species. An estimated date for its appearance in mammalian hosts has been put at the period 1882–1913. This ancestor virus diverged about 1913–1915 into two

clades (or biological groups), which gave rise to the classical swine and human

H1N1

influenza lineages. The last common ancestor of human strains dates to

between February 1917 and April 1918. Because pigs are more readily

infected with avian influenza viruses than are humans, they were

suggested as the original recipients of the virus, passing the virus to

humans sometime between 1913 and 1918.

An effort to recreate the 1918 flu strain (a subtype of avian strain H1N1) was a collaboration among the

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the

USDA ARS Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory and

Mount Sinai School of Medicine in

New York City.

The effort resulted in the announcement (on 5 October 2005) that the

group had successfully determined the virus's genetic sequence, using

historic tissue samples recovered by pathologist

Johan Hultin from a female flu victim buried in the Alaskan

permafrost and samples preserved from American soldiers.

[100]

On 18 January 2007, Kobasa et al. (2007) reported that monkeys (

Macaca fascicularis) infected with the recreated flu strain exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic, and died from a

cytokine storm—an overreaction of the

immune system.

This may explain why the 1918 flu had its surprising effect on younger,

healthier people, as a person with a stronger immune system would

potentially have a stronger overreaction.

[102]

On 16 September 2008, the body of British politician and diplomat

Sir Mark Sykes was exhumed to study the RNA of the flu virus in efforts to understand the genetic structure of modern

H5N1 bird flu. Sykes had been buried in 1919 in a lead coffin which scientists hoped had helped preserve the virus.

[103]

However, the coffin was found to be split because of the weight of soil

over it, and the cadaver was badly decomposed. Nonetheless, samples of

lung and brain tissue were taken through the split, with the coffin

remaining

in situ in the grave during this process.

[104]

In December 2008, research by

Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the

University of Wisconsin

linked the presence of three specific genes (termed PA, PB1, and PB2)

and a nucleoprotein derived from 1918 flu samples to the ability of the

flu virus to invade the lungs and cause pneumonia. The combination

triggered similar symptoms in animal testing.

In June 2010, a team at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported the

2009 flu pandemic vaccine provided some cross-protection against the 1918 flu pandemic strain.

One of the few things known for certain about the influenza in 1918

and for some years after was that it was, out of the laboratory,

exclusively a disease of human beings.

In 2013, the AIR Worldwide Research and Modeling Group "characterized

the historic 1918 pandemic and estimated the effects of a similar

pandemic occurring today using the AIR Pandemic Flu Model". In the

model, "a modern day "Spanish flu" event would result in additional life

insurance losses of between USD 15.3–27.8 billion in the United States

alone" with 188,000–337,000 deaths in the United States.

In popular culture

The 1995 film

Outbreak,

[109] the 2011 film

Contagion and the 2013 film

World War Z make reference to the pandemic.

[110]

The television show

Resurrection

uses the pandemic, in the episode "Afflictions" that aired on November

2, 2014, as the explanation for why many of the Returned were getting

sick and disappearing.

In season four of British drama

Upstairs, Downstairs,

Hazel Bellamy dies of Spanish flu in 1918, after her husband James

Bellamy survives injuries in the "Great War" (World War I). Her funeral

takes place on 11 November, the day the war ends.

In season two of British drama

Downton Abbey, Lavinia Swire dies of the Spanish flu in April 1919, after her fiancé

Matthew Crawley recovers from injuries and temporary paralysis from the Great War.

Twentieth-century fiction includes at least three novels with the flu pandemic as a major theme: Katherine Anne Porter's

Pale Horse, Pale Rider, Thomas Mullen's

The Last Town on Earth, and Thomas Wolfe's

Look Homeward, Angel.

In the one-act play

1918 by

Horton Foote (part of his

Orphans' Home Cycle

(1979)), the presence and threat of the flu (and the tragedy it

ultimately causes) is a major element of the plot. The play was made

into a

film of the same title, released in 1985, which was subsequently edited for broadcast by

PBS as the last part of the miniseries "The Story of A Marriage".

![\frac{N_i}{N} =

\frac{1}{Z}

\exp \left[

-\frac{p_{i, x}^2 + p_{i, y}^2 + p_{i, z}^2}{2mkT}

\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8dc173ee0113a100c4713d64801c5f4d028cff71)

![f_\mathbf{p} (p_x, p_y, p_z) =

\frac{c}{Z}

\exp \left[

-\frac{p_x^2 + p_y^2 + p_z^2}{2mkT}

\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c4d3859f110a3d7bdfd33719a5aaf1e6227212ed)

![f_\mathbf{p} (p_x, p_y, p_z) =

\left( 2 \pi mkT \right)^{-3/2}

\exp \left[

-\frac{p_x^2 + p_y^2 + p_z^2}{2mkT}

\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/76fdc75e9040e7fa2bb88d60729f7183c2b1bf1a)

![{\displaystyle f_{\epsilon }(\epsilon )\,d\epsilon ={\sqrt {\frac {1}{\pi \epsilon kT}}}~\exp \left[{\frac {-\epsilon }{kT}}\right]\,d\epsilon }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9d0b957722f14b4f35ca02434218927e2ffff4d4)

![f_{{\mathbf {v}}}(v_{x},v_{y},v_{z})=\left({\frac {m}{2\pi kT}}\right)^{{3/2}}\exp \left[-{\frac {m(v_{x}^{2}+v_{y}^{2}+v_{z}^{2})}{2kT}}\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efc0617ed7d78e1282e9dffef06398cadf8b74b9)

![f_v (v_i) =

\sqrt{\frac{m}{2 \pi kT}}

\exp \left[

\frac{-mv_i^2}{2kT}

\right].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86a6d2151bda2079488be11059d0320477fb8eb8)