From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_Muslims_during_the_Ottoman_contraction

During the decline and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Muslim (including Ottoman Turks, Albanians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Serb Muslims, Greek Muslims, Muslim Roma, Pomaks) inhabitants living in territories previously under Ottoman control, often found themselves as a persecuted minority after borders were re-drawn. These populations were subject to genocide, expropriation, massacres, and ethnic cleansing.

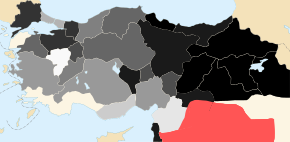

The 19th century saw the rise of nationalism in the Balkans coincident with the decline of Ottoman power, which resulted in the establishment of an independent Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria and Romania. At the same time, the Russian Empire expanded into previously Ottoman-ruled or Ottoman-allied regions of the Caucasus and the Black Sea region. These conflicts created large numbers of Muslim refugees. Persecutions of Muslims resumed during World War I by the invading Russian troops in the east and during the Turkish War of Independence in the west, east, and south of Anatolia by Greeks and Armenians. After the Greco-Turkish War, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey took place, and most Muslims of Greece left. During these times many Muslim refugees, called Muhacir, settled in Turkey.

Background

Turkish presence and Islamisation of native peoples in the Balkans

For the first time, Ottoman military expeditions shifted from Anatolia to Europe and the Balkans with the occupation of the Gallipoli peninsula in the 1350s. After the region was conquered by the Muslim Ottoman Empire, the Turkish presence grew. Some of the settlers were Yörüks, nomads who quickly became sedentary, and others were from urban classes. They settled in almost all of the towns, but the majority of them settled in the Eastern Balkans. The main areas of settlement were Ludogorie, Dobrudzha, the Thracian plain, the mountains and plains of northern Greece and Eastern Macedonia around the Vardar river.

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, large numbers of native Balkan peoples converted to Islam. Places of mass conversions were in Bosnia, Albania, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Crete, and the Rhodope Mountains. Some of the native population converted to Islam and became Turkish over time, mainly those in Anatolia.

Motives for persecution

Hall points out that atrocities were committed by all sides during the Balkan conflicts. Deliberate terror was designed to instigate population movements out of particular territories. The aim of targeting the civilian population was to carve ethnically homogeneous countries.

Great Turkish War

Even before the Great Turkish War (1683—1699) Austrians and Venetians supported Christian irregulars and rebellious highlanders of Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania to raid Muslim Slavs.

The end of the Great Turkish War marked the first time the Ottoman Empire lost large areas of territory to Christians. Most of Hungary, Podolia, and the Morea was lost. The Ottomans regained the Morea quickly, and Muslims soon became part of the population or were never thoroughly displaced in the first place.

Most of the Christians who lived in the Ottoman Empire were Orthodox, so Russia was particularly interested in them. In 1711 Peter the Great invited Balkan Christians to revolt against Ottoman Muslim rule.

Hungary

After the Siege of Pécs, local Muslims were forced to convert to Catholicism between 1686 and 1713, or left the region. The city of Hatvan became a haven for Turkish merchants and became a majority Muslim settlement, but after it fell to the Hungarian troops in 1686, all Turkish settlers were forcibly expelled and their holds in the city became property of foreign mercenaries that fought in the Liberation of Buda.

Croatia

About one quarter of all people living in Slavonia in the 16th century were Muslims who mostly lived in towns, with Osijek and Požega being the largest Muslim settlements. Like other Muslims who lived in Croatia (Lika and Kordun) and Dalmatia, they were all forced to leave their homes by the end of 1699. This was the first example of the cleansing of Muslims in this region. This cleansing of Muslims "enjoyed the benediction of Catholic church". Around 130,000 Muslims from Croatia and Slavonia were driven to Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina. Basically, all Muslims who lived in Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia were either forced to exile, murdered or enslaved.

Thousands of Serb refugees crossed the Danube and populated territories of Habsburg Monarchy left by Muslims. Leopold I granted ethno-religious autonomy to them without giving any privileges to the remaining Muslim population who therefore fled to Bosnia, Herzegovina and Serbia spreading anti-Christian sentiment among other Muslims there. The relations between non-Muslim and Muslim population of Ottoman held Balkans became progressively worse.

At the beginning of the 18th century remaining Muslims of Slavonia moved to Posavina. The Ottoman authorities encouraged hopes of expelled Muslims for a quick return to their homes and settled them in the border regions. The Muslims comprised about 2/3 population of Lika. All of them, like Muslims who lived in other parts of Croatia, were forced to convert to Catholicism or to be expelled. Almost all Ottoman buildings were destroyed in Croatia, after the Ottomans left.

Northern Bosnia

In 1716, Austria occupied northern Bosnia alongside northern Serbia until 1739 when those lands were ceded back to the Ottoman Empire at the Treaty of Belgrade. During this era, the Austrian Empire outlined its position to the Bosnian Muslim population about living within its administration. Two options were offered by Charles VI such as a conversion to Christianity while retaining property and remaining on Austrian territory, or for a departure of those remaining Muslim to other lands.

Montenegro

At the beginning of the 18th century (1709 or 1711) Orthodox Serbs massacred their Muslim neighbors in Montenegro.

National movements

Serbian Revolution

After the Dahije, renegade janissaries who defied the Sultan and ruled the Sanjak of Smederevo in tyranny (beginning in 1801), imposing harsh taxes and forced labour, went on to execute leading Serbs throughout the sanjak in 1804, the Serbs rose up against the Dahije. The revolt, known as the First Serbian Uprising, subsequently reached national level after the quick success of the Serbs. The Porte, seeing the Serbs as a threat, ordered their disbandment. The revolutionaries took over Belgrade in 1806 where an armed uprising against a Muslim garrison, including civilians, took place. During the uprising urban centers with sizeable Muslim populations were violently targeted such as Užice and Valjevo, as the Serbian peasantry held a class hatred of the urban Muslim elite. In the end, Serbia became an autonomous country and most of the Muslims were expelled. During the revolts 15,000–20,000 Muslims fled or were expelled. In Belgrade and the rest of Serbia there remained a Muslim population of some 23,000 who were also forcibly expelled after 1862, following a massacre of Serbian civilians by Ottoman soldiers near Kalemegdan. Some Muslim families then migrated and resettled in Bosnia, where their descendants today reside in urban centres such as Šamac, Tuzla, Foča and Sarajevo.

Greek Revolution

In 1821, a major Greek revolt broke out in Southern Greece. Insurgents gained control of most of the countryside while the Muslims and Jews sheltered themselves in the fortified towns and castles. Each one of them was besieged and gradually through starvation or surrender most were taken over by the Greeks. In the massacres of April 1821 some 15,000 were killed. The worst massacre happened in Tripolitsa, some 8,000 Muslims and Jews died. In response, massive reprisals against Greeks in Constantinople, Smyrna, Cyprus, and elsewhere, took place; thousands were killed and the Ottoman Sultan even considered a policy of total extermination of all Greeks in the Empire. In the end an independent Greece was set up. Most of the Muslims in its area had been killed or expelled during the conflict. British historian William St Clair argues that what he calls "the genocidal process" ended when there were no more Turks to kill in what would become independent Greece.

Bulgarian uprising

In 1876 a Bulgarian uprising broke out in dozens of villages. The first attacks were made against the local Muslims but in a short time the Ottomans violently suppressed the uprising.

From 1876 until 1989, Muslims from Bulgaria (Turks, Tatars, Pomaks and Muslim Roma) were expelled to Turkey; such as during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Balkan Wars (1912-1913), and the 1989 expulsion of Turks from Bulgaria.

Russo-Turkish war

Bulgaria

The Bulgarian uprising eventually lead to a war between Russia and the Ottomans. Russia invaded the Ottoman Balkans through Dobrudzha and northern Bulgaria attacking the Muslim population. In this war the Ottomans were defeated, and in the process nearly half of the Muslims in Bulgaria fled to Constantinople and Anatolia. It was a cold winter and a large part of them died. Some of them returned after the war but most of these left again. The Bulgarian Muslims (part of them Turks) settled mostly around the Sea of Marmara. Some of them had been wealthy and they played an important part in the Ottoman elite in later years. Almost half of the pre-war 1,5 million Muslim population of Bulgaria was gone, an estimated 200,000 died and the rest fled.

Migration continued in the peacetime, some 350,000 Bulgarian Muslims left the country between 1880 and 1911.

Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78)

On the eve of the outbreak of a second round of hostilities between Serbia and the Ottoman Empire in 1877, a notable Muslim population existed in the districts of Niš, Pirot, Vranje, Leskovac, Prokuplje and Kuršumlija. The rural parts of Toplica, Kosanica, Pusta Reka and Jablanica valleys and adjoining semi-mountainous interior was inhabited by compact Muslim Albanian population while Serbs in those areas lived near the river mouths and mountain slopes and both peoples inhabited other regions of the South Morava river basin. The Muslim population of most of the area was composed out of ethnic Gheg Albanians and with Turks located in urban centres. Part of the Turks were of Albanian origin. The Muslims in the cities of Niš and Pirot were Turkish-speaking; Vranje and Leskovac were Turkish- and Albanian-speaking; Prokuplje and Kuršumlija were Albanian-speaking. There was also a minority of Circassian refugees settled by the Ottomans during the 1860s, near the then border around the environs of Niš. Estimates vary on the size of the Muslim population on the eve of the war within these areas ranging from as high as 200,000 to as low as 131,000. Estimates as to the number of the Muslim refugees that left the region for the Ottoman Empire due to the war range from 60–70,000 to as low as 30,000. The departure of the Albanian population from these regions was done in a manner that today would be characterized as ethnic cleansing.

Hostilities between Serbian and Ottoman forces broke out on 15 December 1877, after a Russian request for Serbia to enter the Russo-Turkish war. The Serbian military had two objectives: capturing Niš and breaking the Niš-Sofia Ottoman lines of communication. Serbian forces entered the wider Toplica and Morava valleys capturing urban centres such as Niš, Kuršumlija, Prokuplije, Leskovac, and Vranje and their surrounding rural and mountainous districts. In these regions, the Albanian population depending on the area they resided had fled into nearby mountains, leaving livestock, property and other belongings behind. Some Albanians returned and submitted to Serbian authorities, while others continued their flight southward toward Ottoman Kosovo. Serbian forces also encountered heavy Albanian resistance in certain areas which slowed their advance into these regions resulting in having to take villages one by one that became vacant. A small Albanian population remained the Medveđa area, where their descendants still reside today. The retreat of these refugees toward Ottoman Kosovo was halted at the Goljak Mountains when an armistice was declared. The Albanian population was resettled in Lab area and other parts of northern Kosovo alongside the new Ottoman-Serbian border. Most Albanian refugees were resettled in over 30 large rural settlements in central and southeastern Kosovo and in urban centres that increased their populations substantially. Tensions between Albanian refugees and local Kosovo Albanians arose over resources, as the Ottoman Empire found it difficult to accommodate to their needs and meager conditions. Tensions in the form of revenge attacks also arose by incoming Albanian refugees on local Kosovo Serbs that contributed to the beginnings of the ongoing Serbian-Albanian conflict in coming decades.

Bosnia

In 1875, a conflict between Muslims and Christians broke out in Bosnia. After the Ottoman Empire signed the treaty at the 1878 Berlin Congress, Bosnia was occupied by Austria-Hungary. Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) perceived this as a betrayal by the Ottomans and left on their own, felt that they were defending their homeland and not the wider Empire. From 9 July until 20 October 1878 or for almost three months, Bosnian Muslims resisted Austro-Hungarian forces in nearly sixty military engagements with 5,000 casualties either wounded or killed. Some Bosnian Muslims concerned about their future and well being under the new non-Muslim administration, left Bosnia for the Ottoman Empire. From 1878 until 1918, between 130,000 and 150,000 Bosnian Muslims departed Bosnia to areas under Ottoman control, some to the Balkans, others to Anatolia, the Levant and Maghreb. Today, these Bosnian populations in the Arab world have become assimilated although they have retained memories of their origins and some bear the ethnonym Bosniak (rendered in Arabic as Bushnak) as a surname.

Circassia

The Russo-Circassian War was the 101 year-long military conflict between Circassia and Russia. Circassia was de jure part of the Ottoman Empire but de facto independent. The conflict started in 1763, when the Russian Empire attempted to establish hostile forts in Circassian territory and quickly annex Circassia, followed by the Circassian refusal of the annexation; only ending 101 years later when the last resistance army of Circassia was defeated on 21 May 1864, making it exhausting and casualty heavy for the Russian Empire as well as being the single longest war Russia ever waged in history.

The end of the war saw the Circassian genocide take place in which Imperial Russia aimed to systematically destroy the Circassian people where several war crimes were committed by the Russian forces and up to 1.5 million Circassians were killed or expelled to the Middle East, especially modern-day Turkey. Russian generals such as Grigory Zass described the Circassians as "subhuman filth", and justified their killing and use in scientific experiments.

South Caucasus

The area around Kars was ceded to Russia. This resulted in a large number of Muslims leaving and settling in remaining Ottoman lands. Batum and its surrounding area was also ceded to Russia causing many local Georgian Muslims to migrate to the west. Most of them settled around the Anatolian Black Sea coast.

Balkan Wars

In 1912 Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro declared war on the Ottomans. The Ottomans quickly lost territory. According to Geert-Hinrich Ahrens, "the invading armies and Christian insurgents committed a wide range of atrocities upon the Muslim population." In Kosovo and Albania most of the victims were Albanians while in other areas most of the victims were Turks and Pomaks. A large number of Pomaks in the Rhodopes were forcibly converted to Orthodoxy but later allowed to reconvert, most of them did. During this war hundreds of thousands of the Turks and Pomaks fled their villages and became refugees. The Report of the International Commission on the Balkan Wars reported that in many districts the Moslem villages were systematically burned by their Christian neighbors. In Monastir 80% of the Muslim villages were burned by the Serbian and Greek army according to a British report. While in Giannitsa the Muslim quarter was burned alongside many Muslim villages in the Salonica province by the Greek army. Massacres and rapes are also reported by the Greek and Bulgarian armies towards Turks. Arnold Toynbee gives the number of Muslim refugees who fled the region that fell under Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek control between 1912–1915 as 297,918. Justin Mccarthy gives the number of refugees during and after the Balkan Wars (1912–20) as 413,922, and further states that in the period between 1911–1926 out of the 2,315,293 Muslims that lived in the areas taken from the Ottoman Empire in Europe (excluding Albania), 812,771 ended up in Turkey (including those of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey), 632,408 died, and 870,114 remained. By 1923, only 38% of the Muslim population of 1912 still lived in the Balkans. According to Emre Erol, 410,000 Muslims were displaced to the Ottoman Empire and more than 100,000 died during their flight. Salonika (Thessaloniki) and Adrianople (Edirne) were crowded with them. By sea and land mostly they settled in Ottoman Thrace and Anatolia.

World War I and the Turkish War of Independence

Caucasus Campaign

Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör noted that during the Russian invasion of Ottoman lands, "many atrocities were carried out against the local Turks and Kurds by the Russian army and Armenian volunteers." General Liakhov gave the order to kill any Turk on sight and destroy any mosque. According to Boris Shakhovskoi the Armenian nationalists wanted to exterminate the Muslims in the occupied regions. A large part of the local Muslim Turks and Kurds fled west after the Russian invasion of 1914–1918, in Talaat Pasha's Notebook the given number is at 702,905 Turks. J. Rummel estimates that 128,000-600,000 Muslim Turks and Kurds were killed by Russian troops and Armenian irregulars; at least 128,000 of them between 1914–1915 according to Turkish statistician Ahmet Emin Yalman. After the formation of the Provisional Government in 1917, some 30,000–40,000 Muslims were killed by irregular Armenian units as retribution. Turkish-German historian Taner Akçam in book A Shameful Act writes of Vehip Pasha's detailed account of the reprisals against Muslims during the retreat of Armenian and Russian forces from Western Armenia in 1917–1918, setting the death figure at 3,000 in the Erzincan and Bayburt areas. Writing also of another eyewitness testimony claiming 3,000 dead in the Erzurum area, and 20,000 dead in Kars in the spring of 1918. Akçam also makes mention of a study of the Vilayet of Erzurum which sets the number of massacred Muslims as 25,000 in the spring of 1918, however, providing the examination of Armenian historian Vahakn Dadrian who claims from the wartime records of the Ottoman Third Army that "altogether some 5,000–5,500 victims are involved." Akçam writes of a Turkish source which describes the number of Muslim deaths during the winter and spring of 1919 in Kars as 6,500, whereas on 22 March 1920, Kâzım Karabekir put the number at 2,000 in certain villages and regions in Kars. In April 1918, 800 Muslims were massacred in the Iğdır Province—In 5 July 1920, 25,000 Muslims had been killed in Kars and Iğdır since 1918. Halil Bey in a 1919 letter to Karabekir claimed 24 villages in Iğdır had been razed.

Franco-Turkish War

Cilicia was occupied by the British after World War I, who were later replaced by the French. The French Armenian Legion armed returning Armenian refugees of the Armenian genocide to the region and assisting them. Eventually the Turks responded with resistance against the French occupation, battles took place in Marash, Aintab, and Urfa. Most of these cities were destroyed during the process with large civilian suffering. In Marash, 4.500 Turks died. The French left the area together with the Armenians after 1920. The retribution for the Armenian Genocide served as justification for armed Armenians.

Also during the Franco-Turkish War, the Kaç Kaç incident occurred, which refers to the escape of 40,000 Turks from the city of Adana into more mountainous regions due to the Franco-Armenian operation of July 20, 1920. During the escape, French-Armenian airplanes bombed the fleeing population and the Belemedik hospital.

Greco–Turkish War

After the Greek landing and the following occupation of Western Anatolia during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), the Turkish resistance activity was answered with terror against the local Muslims. Killings, rapes, and village burnings took place as the Greek Army advanced. However, as reported in a British intelligence report at the time, in general "the [Turkish] inhabitants of the occupied zone have in most cases accepted the advent of Greek rule without demur and in some cases undoubtedly prefer it to the [Turkish] Nationalist regime which seems to have been founded on terrorism". British military personnel observed that the Greek army near Uşak was warmly welcomed by the Muslim population for "being freed from the license and oppression of the [Turkish] Nationalist troops"; there were "occasional cases of misconduct" by the Greek troops against the Muslim population, and the perpetrators were prosecuted by the Greek authorities, while the "worst miscreants" were "a handful of Armenians recruited by the Greek army", who were then sent back to Constantinople.

During the Greek occupation, Greek troops and local Greeks, Armenian, and Circassian groups committed the Yalova Peninsula Massacres in early 1921 against the local Muslim population. These resulted, according to some sources, in the deaths of c. 300 of the local Muslim populace, as well c. 27 villages. Precise number of casualties is not exactly known. Statements gathered by Ottoman official, reveal a relatively low number of casualties: based on the Ottoman enquiry to which 177 survivors responded, only 35 were reported as killed, wounded or beaten or missing. This is also in accordance with Toynbee's accounts that one to two murders were enough to drive out the population. Another source estimates that barely 1.500 Muslims out of 7,000 survived in the environment of Yalova.

The Greeks advanced all the way to Central Anatolia. After the Turkish attack in 1922 the Greeks retreated and Norman M. Naimark notes that "the Greek retreat was even more devastating for the local population than the occupation". During the retreat, towns and villages were burned as part of a scorched earth policy, accompanied with massacres and rapes. During this war, a part of Western Anatolia was destroyed, large towns such as Manisa, Salihli together with many villages being burned. 3000 houses in Alaşehir. The Inter-Allied commission, consisting of British, French, American and Italian officers found that "there is a systematic plan of destruction of Turkish villages and extinction of the Muslim population." According to Marjorie Housepian, 4000 Muslims were executed in Izmir under Greek occupation.

During the war, in East Thrace (which was ceded to Greece with the Treaty of Sèvres), around 90,000 Turkish villagers fled to Bulgaria and Istanbul from the Greeks.

After the war, peace talks between Greece and Turkey started with the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923. At the Conference, the chief negotiator of the Turkish delegation, Ismet Pasha, gave an estimate of 1.5 million Anatolian Turks that had been exiled or died in the area of Greek occupation. Of these, McCarthy estimates that 860,000 fled and 640,000 died; with many, if not most of those who died, being refugees as well. The comparison of census figures shows that 1,246,068 Anatolian Muslims had become refugees or had died. Furthermore, Ismet Pasha shared statistics showing the destruction of 141,874 buildings, and the slaughter or theft of 3,291,335 farm animals in the area of Greek occupation. The peace that followed the Greco–Turkish War resulted in a population exchange between Greece and Turkey. As a result, the Muslim population of Greece, with the exception of Western Thrace, and partially, the Muslim Cham Albanians, was relocated to Turkey.

Total casualties

The forced mass displacement of Muslims out of the Balkans during the era of territorial contraction of the Ottoman Empire has only become a topic of recent scholarly interest in the 21st century.

Death toll

According to historian Justin McCarthy, between the years 1821–1922, from the beginning of the Greek War of Independence to the end of the Ottoman Empire, five million Muslims were driven from their lands and another five and a half million died, some of them killed in wars, others perishing as refugees from starvation or disease. However, McCarthy's work has faced harsh criticism by many scholars who have characterized his views as indefensibly biased towards Turkey and defending Turkish atrocities against Armenians, as well as engaging in genocide denial.

According to Matthew Gibney, the total Muslim refugees during these centuries are estimated to be several millions. Roger Owen estimates that during the last decade of the Ottoman Empire (1912–1922) when the Balkan wars, World War I and war of Independence took place, close to 2 million Muslims, civilian and military, died in the area of modern Turkey.

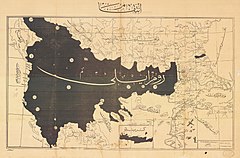

Settlement of refugees

The Ottoman authorities and charities provided some help to the immigrants and sometimes settled them in certain locations. In Turkey most of the Balkan refugees settled in Western Turkey and Thrace. The Caucasians, in addition to these areas also settled in Central Anatolia and around the Black Sea coast. Eastern Anatolia was not largely settled with the exception of some Circassian and Karapapak villages. There were also completely new villages founded by refugees, for example in uninhabited forested areas. Many people of the 1924 exchange were settled in former Greek villages along the Aegean coast. Outside of Turkey, Circassians were settled along the Hedjaz Railway and some Cretan Muslims at Syria's coast.

Academic debate

According to Michael Mann McCarthy is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate over Balkan Muslim death figures. Mann however states that even if those figures were reduced "by as much as 50 percent, they still would horrify". In the discussion about the Armenian Genocide, McCarthy denies the genocide and is considered as the leading pro-Turkish scholar. Scholarly critics of McCarthy acknowledge that his research on Muslim civilian casualties and refugee numbers (19th and early 20th centuries) has brought forth a valuable perspective, previously neglected in the Christian West: that millions of Muslims and Jews also suffered and died during these years. Donald W. Bleacher, though acknowledging that McCarthy is pro-Turkish nonetheless has called his scholarly study Death and Exile on Muslim civilian casualties and refugee numbers "a necessary corrective" challenging the West's model of all victims being Christians and all perpetrators as being Muslims.

Historian Mark Biondich estimates that from 1878–1912 up to two million Muslims left the Balkans either voluntarily or involuntarily while Muslims casualties in the Balkans during 1912–1923 within the context of those killed and expelled exceeded some three million.

Destruction of Muslim heritage

Muslim heritage was extensively targeted during the persecutions. During their long rule the Ottomans had built numerous mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, bath-houses and other types of building. According to current research, around 20,000 buildings of all sizes have been documented in official Ottoman registers. However very little survives of this Ottoman heritage in most Balkan countries. Most of the Ottoman era mosques of the Balkans have been destroyed; the ones still standing often had their minarets destroyed. Before the Habsburg conquest, Osijek had 8–10 mosques, none of which remain today. During the Balkan wars there were cases of desecration, destruction of mosques and Muslim cemeteries. Of the 166 madrasas in the Ottoman Balkans in the 17th century, only eight remain and five of them are near Edirne. It is estimated that 95–98% were destroyed. The same is also valid for other types of buildings, such as markethalls, caravanserais and baths. From a chain of caravanserais across the Balkans only one is preserved while there are vague ruins of four others. There were in the area of Negroponte in 1521: 34 large and small mosques, six hamams, ten schools, and 6 dervish convents. Today only the ruin of one hamam remains.

| Town | During Ottoman rule | Still standing |

|---|---|---|

| Shumen | 40 | 3 |

| Serres | 60 | 3 |

| Belgrade | >100 | 1 |

| Sofia | >100 | 1 |

| Ruse | 36 | 1 |

| Sremska Mitrovica | 17 | 0 |

| Osijek | 7 | 0 |

| Požega | 14—15 | 0 |

Commemoration

There exists literature in Turkey dealing with these events, but outside of Turkey, the events are largely unknown to the world public.

Impact on Europe

According to Mark Levene, the Victorian public in the 1870s paid much more attention to the massacres and expulsions of Christians than to massacres and expulsions of Muslims, even if on a greater scale. He further suggests that such massacres were even favored by some circles. Mark Levene also argues that the dominant powers, by supporting "nation-statism" at the Congress of Berlin, legitimized "the primary instrument of Balkan nation-building": ethnic cleansing.

Memorials

There is a monument in Iğdır, Turkey, called Iğdır Genocide Memorial and Museum, remembering the Muslim victims of World War I.

A monument was erected in Anaklia, Georgia on 21 May 2012, to commemorate the expulsion of the Circassians.