From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The thorium fuel cycle is a nuclear fuel cycle that uses the isotope of thorium, 232Th, as the fertile material. In the reactor, 232Th is transmuted into the fissile artificial uranium isotope 233U which is the nuclear fuel. Unlike natural uranium, natural thorium contains only trace amounts of fissile material (such as 231Th), which are insufficient to initiate a nuclear chain reaction. Additional fissile material or another neutron source are necessary to initiate the fuel cycle. In a thorium-fueled reactor, 232Th absorbs neutrons eventually to produce 233U. This parallels the process in uranium breeder reactors whereby fertile 238U absorbs neutrons to form fissile 239Pu. Depending on the design of the reactor and fuel cycle, the generated 233U either fissions in situ or is chemically separated from the used nuclear fuel and formed into new nuclear fuel.

The thorium fuel cycle claims several potential advantages over a uranium fuel cycle, including thorium's greater abundance, superior physical and nuclear properties, better resistance to nuclear weapons proliferation[1][2][3] and reduced plutonium and actinide production.[3]

History

Concerns about the limits of worldwide uranium resources motivated initial interest in the thorium fuel cycle.[4] It was envisioned that as uranium reserves were depleted, thorium would supplement uranium as a fertile material. However, for most countries uranium was relatively abundant and research in thorium fuel cycles waned. A notable exception was India's three-stage nuclear power programme.[5] In the twenty-first century thorium's potential for improving proliferation resistance and waste characteristics led to renewed interest in the thorium fuel cycle.[6][7][8]At Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the 1960s, the Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment used 233U as the fissile fuel as an experiment to demonstrate a part of the Molten Salt Breeder Reactor that was designed to operate on the thorium fuel cycle. Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) experiments assessed thorium's feasibility, using thorium(IV) fluoride dissolved in a molten salt fluid that eliminated the need to fabricate fuel elements. The MSR program was defunded in 1976 after its patron Alvin Weinberg was fired.[9]

In 2006, Carlo Rubbia proposed the concept of an energy amplifier or "accelerator driven system" (ADS), which he saw as a novel and safe way to produce nuclear energy that exploited existing accelerator technologies. Rubbia's proposal offered the potential to incinerate high-activity nuclear waste and produce energy from natural thorium and depleted uranium.[10][11]

Kirk Sorensen, former NASA scientist and Chief Nuclear Technologist at Teledyne Brown Engineering, has been a long-time promoter of thorium fuel cycle and particularly liquid fluoride thorium reactors (LFTRs). He first researched thorium reactors while working at NASA, while evaluating power plant designs suitable for lunar colonies. In 2006 Sorensen started "energyfromthorium.com" to promote and make information available about this technology.[12]

A 2011 MIT study concluded that, although there is little in the way of barriers to a thorium fuel cycle, with current or near term light-water reactor designs there is also little incentive for any significant market penetration to occur. As such they conclude there is little chance of thorium cycles replacing conventional uranium cycles in the current nuclear power market, despite the potential benefits.[13]

Nuclear reactions with thorium

"Thorium is like wet wood […it] needs to be turned into fissile uranium just as wet wood needs to be dried in a furnace."

n+232 90Th→233 90Th−→−β−233 91Pa−→−β−233 92U

Fission product wastes

Nuclear fission produces radioactive fission products which can have half-lives from days to greater than 200,000 years. According to some toxicity studies,[15] the thorium cycle can fully recycle actinide wastes and only emit fission product wastes, and after a few hundred years, the waste from a thorium reactor can be less toxic than the uranium ore that would have been used to produce low enriched uranium fuel for a light water reactor of the same power. Other studies assume some actinide losses and find that actinide wastes dominate thorium cycle waste radioactivity at some future periods.[16]Actinide wastes

In a reactor, when a neutron hits a fissile atom (such as certain isotopes of uranium), it either splits the nucleus or is captured and transmutes the atom. In the case of 233U, the transmutations tend to produce useful nuclear fuels rather than transuranic wastes. When 233U absorbs a neutron, it either fissions or becomes 234U. The chance of fissioning on absorption of a thermal neutron is about 92%; the capture-to-fission ratio of 233U, therefore, is about 1:12 — which is better than the corresponding capture vs. fission ratios of 235U (about 1:6), or 239Pu or 241Pu (both about 1:3).[4][17] The result is less transuranic waste than in a reactor using the uranium-plutonium fuel cycle.| 230Th | → | 231Th | ← | 232Th | → | 233Th | (White actinides: t½<27d p=""> | |||||||

| ↓ | ↓ | |||||||||||||

| 231Pa | → | 232Pa | ← | 233Pa | → | 234Pa | (Colored : t½>68y) | |||||||

| ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||||||||||

| 231U | ← | 232U | ↔ | 233U | ↔ | 234U | ↔ | 235U | ↔ | 236U | → | 237U | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||||||||||

| (Fission products with t½<90y or="" sub="" t="">½ | ||||||||||||||

However, the 231Pa (with a half-life of 3.27×104 years) formed via (n,2n) reactions with 232Th (yielding 231Th that decays to 231Pa), while not a transuranic waste, is a major contributor to the long-term radiotoxicity of spent nuclear fuel.

Uranium-232 contamination

Uranium-232 is also formed in this process, via (n,2n) reactions between fast neutrons and 233U, 233Pa, and 232Th:

n+232 90Th→233 90Th−→−β−233 91Pa−→−β−233 92U+n→232 92U+2n n+232 90Th→233 90Th−→−β−233 91Pa+n→232 91Pa+2n−→−β−232 92U

232 92U−→ α 228 90Th (68.9 years) 228 90Th−→ α 224 88Ra (1.9 year)

224 88Ra−→ α 220 86Rn (3.6 day, 0.24 MeV)

220 86Rn−→ α 216 84Po (55 s, 0.54 MeV)

216 84Po−→ α 212 82Pb (0.15 s)

212 82Pb−→−β− 212 83Bi (10.64 h)

212 83Bi−→ α 208 81Tl (61 m, 0.78 MeV)

Nuclear fuel

As a fertile material thorium is similar to 238U, the major part of natural and depleted uranium. The thermal neutron absorption cross section (σa) and resonance integral (average of neutron cross sections over intermediate neutron energies) for 232Th are about three times and one third of the respective values for 238U.Advantages

Thorium is estimated to be about three to four times more abundant than uranium in Earth's crust,[18] although present knowledge of reserves is limited. Current demand for thorium has been satisfied as a by-product of rare-earth extraction from monazite sands.Although the thermal neutron fission cross section (σf) of the resulting 233U is comparable to 235U and 239Pu, it has a much lower capture cross section (σγ) than the latter two fissile isotopes, providing fewer non-fissile neutron absorptions and improved neutron economy. Finally, the ratio of neutrons released per neutron absorbed (η) in 233U is greater than two over a wide range of energies, including the thermal spectrum; as a result, thorium-based fuels can be the basis for a thermal breeder reactor.[4] A breeding reactor in the uranium - plutonium cycle needs to use a fast neutron spectrum, because in the thermal spectrum one neutron absorbed by 239Pu on average leads to less than two neutrons.

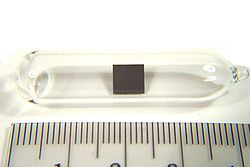

Thorium-based fuels also display favorable physical and chemical properties that improve reactor and repository performance. Compared to the predominant reactor fuel, uranium dioxide (UO

2), thorium dioxide (ThO

2) has a higher melting point, higher thermal conductivity, and lower coefficient of thermal expansion. Thorium dioxide also exhibits greater chemical stability and, unlike uranium dioxide, does not further oxidize.[4]

Because the 233U produced in thorium fuels is inevitably contaminated with 232U, thorium-based used nuclear fuel possesses inherent proliferation resistance. 232U can not be chemically separated from 233U and has several decay products that emit high-energy gamma radiation. These high-energy photons are a radiological hazard that necessitate the use of remote handling of separated uranium and aid in the passive detection of such materials. 233U can be denatured by mixing it with natural or depleted uranium, requiring isotope separation before it could be used in nuclear weapons.

The long-term (on the order of roughly 103 to 106 years) radiological hazard of conventional uranium-based used nuclear fuel is dominated by plutonium and other minor actinides, after which long-lived fission products become significant contributors again. A single neutron capture in 238U is sufficient to produce transuranic elements, whereas six captures are generally necessary to do so from 232Th. 98–99% of thorium-cycle fuel nuclei would fission at either 233U or 235U, so fewer long-lived transuranics are produced. Because of this, thorium is a potentially attractive alternative to uranium in mixed oxide (MOX) fuels to minimize the generation of transuranics and maximize the destruction of plutonium.[19]

Disadvantages

There are several challenges to the application of thorium as a nuclear fuel, particularly for solid fuel reactors:Unlike uranium, natural thorium contains no fissile isotopes; fissile material, generally 233U, 235U or plutonium, must be added to achieve criticality. This, along with the high sintering temperature necessary to make thorium-dioxide fuel, complicates fuel fabrication. Oak Ridge National Laboratory experimented with thorium tetrafluoride as fuel in a molten salt reactor from 1964–1969, which was expected to be easier to process and separate from contaminants that slow or stop the chain reaction.

In an open fuel cycle (i.e. utilizing 233U in situ), higher burnup is necessary to achieve a favorable neutron economy. Although thorium dioxide performed well at burnups of 170,000 MWd/t and 150,000 MWd/t at Fort St. Vrain Generating Station and AVR respectively,[4] challenges complicate achieving this in light water reactors (LWR), which compose the vast majority of existing power reactors.

In a once-through thorium fuel cycle the residual 233U is a long-lived radioactive isotope in the waste.

Another challenge associated with the thorium fuel cycle is the comparatively long interval over which 232Th breeds to 233U. The half-life of 233Pa is about 27 days, which is an order of magnitude longer than the half-life of 239Np. As a result, substantial 233Pa develops in thorium-based fuels. 233Pa is a significant neutron absorber, and although it eventually breeds into fissile 235U, this requires two more neutron absorptions, which degrades neutron economy and increases the likelihood of transuranic production.

Alternatively, if solid thorium is used in a closed fuel cycle in which 233U is recycled, remote handling is necessary for fuel fabrication because of the high radiation levels resulting from the decay products of 232U. This is also true of recycled thorium because of the presence of 228Th, which is part of the 232U decay sequence. Further, unlike proven uranium fuel recycling technology (e.g. PUREX), recycling technology for thorium (e.g. THOREX) is only under development.

Although the presence of 232U complicates matters, there are public documents showing that 233U has been used once in a nuclear weapon test. The United States tested a composite 233U-plutonium bomb core in the MET (Military Effects Test) blast during Operation Teapot in 1955, though with much lower yield than expected.[20]

Though thorium-based fuels produce far less long-lived transuranics than uranium-based fuels,[15] some long-lived actinide products constitute a long-term radiological impact, especially 231Pa.[16]

Advocates for liquid core and molten salt reactors such as LFTR claim that these technologies negate thorium's disadvantages present in solid fueled reactors. As only two liquid-core fluoride salt reactors have been built (the ORNL ARE and MSRE) and neither have used thorium, it is hard to validate the exact benefits.[4]

Reactors

Thorium fuels have fueled several different reactor types, including light water reactors, heavy water reactors, high temperature gas reactors, sodium-cooled fast reactors, and molten salt reactors.[21]List of thorium-fueled reactors[edit]

From IAEA TECDOC-1450 "Thorium Fuel Cycle - Potential Benefits and Challenges", Table 1: Thorium utilization in different experimental and power reactors.[4] Additionally, Dresden 1 in the USA used "thorium oxide corner rods".[22]| Name | Country | Type | Power | Fuel | Operation period |

| AVR | Germany | HTGR, experimental (pebble bed reactor) | 15 MW(e) | Th+235U Driver fuel, coated fuel particles, oxide & dicarbides | 1967–1988 |

| THTR-300 | Germany | HTGR, power (pebble type) | 300 MW(e) | Th+235U, Driver fuel, coated fuel particles, oxide & dicarbides | 1985–1989 |

| Lingen | Germany | BWR irradiation-testing | 60 MW(e) | Test fuel (Th,Pu)O2 pellets | 1968-1973 |

| Dragon (OECD-Euratom) | UK (also Sweden, Norway & Switzerland) | HTGR, Experimental (pin-in-block design) | 20 MWt | Th+235U Driver fuel, coated fuel particles, oxide & dicarbides | 1966–1973 |

| Peach Bottom | USA | HTGR, Experimental (prismatic block) | 40 MW(e) | Th+235U Driver fuel, coated fuel particles, oxide & dicarbides | 1966–1972 |

| Fort St Vrain | USA | HTGR, Power (prismatic block) | 330 MW(e) | Th+235U Driver fuel, coated fuel particles, Dicarbide | 1976–1989 |

| MSRE ORNL | USA | MSBR | 7.5 MWt | 233U molten fluorides | 1964–1969 |

| BORAX-IV & Elk River Station | USA | BWR (pin assemblies) | 2.4 MW(e); 24 MW(e) | Th+235U Driver fuel oxide pellets | 1963 - 1968 |

| Shippingport | USA | LWBR PWR, (pin assemblies) | 100 MW(e) | Th+233U Driver fuel, oxide pellets | 1977–1982 |

| Indian Point 1 | USA | LWBR PWR, (pin assemblies) | 285 MW(e) | Th+233U Driver fuel, oxide pellets | 1962–1980 |

| SUSPOP/KSTR KEMA | Netherlands | Aqueous homogenous suspension (pin assemblies) | 1 MWt | Th+HEU, oxide pellets | 1974–1977 |

| NRX & NRU | Canada | MTR (pin assemblies) | 20MW; 200MW (see) | Th+235U, Test Fuel | 1947 (NRX) + 1957 (NRU); Irradiation–testing of few fuel elements |

| CIRUS; DHRUVA; & KAMINI | India | MTR thermal | 40 MWt; 100 MWt; 30 kWt (low power, research) | Al+233U Driver fuel, ‘J’ rod of Th & ThO2, ‘J’ rod of ThO2 | 1960-2010 (CIRUS); others in operation |

| KAPS 1 & 2 KGS 1 & 2 RAPS 2, 3 & 4 | India | PHWR, (pin assemblies) | 220 MW(e) | ThO2 pellets (for neutron flux flattening of initial core after start-up) | 1980 (RAPS 2) +; continuing in all new PHWRs |

| FBTR | India | LMFBR, (pin assemblies) | 40 MWt | ThO2 blanket | 1985; in operation |