| Much Ado About Nothing | |

|---|---|

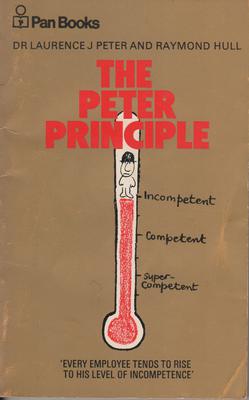

The title page from the first quarto edition of Much Adoe About Nothing, printed in 1600 | |

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Characters | Antonio Balthasar Beatrice Benedick Borachio Claudio Conrade Dogberry Don John Don Pedro Friar Frances Hero Innogen Leonato Margaret Ursula Verges |

| Date premiered | 1600 |

| Original language | Early Modern English |

| Genre | Comedy |

| Setting | Messina, Italy |

Much Ado About Nothing is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599. The play was included in the First Folio, published in 1623.

The play is set in Messina and revolves around two romantic pairings that emerge when a group of soldiers arrive in the town. The first, between Claudio and Hero, is nearly scuppered by the accusations of the villain, Don John. The second, between Claudio's friend Benedick and Hero's cousin Beatrice, takes centre stage as the play continues, with both characters' wit and banter providing much of the humour.

Through "noting" (sounding like "nothing" and meaning gossip, rumour, overhearing), Benedick and Beatrice are tricked into confessing their love for each other, and Claudio is tricked into believing that Hero is not a maiden (virgin). The title's play on words references the secrets and trickery that form the backbone of the play's comedy, intrigue, and action.

Characters

- Benedick, a lord and soldier from Padua; companion of Don Pedro

- Beatrice, niece of Leonato

- Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon

- Don John, "the Bastard Prince", brother of Don Pedro

- Claudio, of Florence; a count, companion of Don Pedro, friend to Benedick

- Leonato, governor of Messina; Hero's father

- Antonio, brother of Leonato

- Balthasar, attendant on Don Pedro, a singer

- Borachio, follower of Don John

- Conrade, follower of Don John

- Innogen, a 'ghost character' in early editions as Leonato's wife

- Hero, daughter of Leonato

- Margaret, waiting-gentlewoman attendant on Hero

- Ursula, waiting-gentlewoman attendant on Hero

- Dogberry, the constable in charge of Messina's night watch

- Verges, the Headborough, Dogberry's partner

- Friar Francis, a priest

- a Sexton, the judge of the trial of Borachio

- a Boy, serving Benedick

- The Watch, watchmen of Messina

- Attendants and Messengers

Synopsis

In Messina, a messenger brings news that Don Pedro will return that night from a successful battle, along with Claudio and Benedick. Beatrice asks the messenger about Benedick and mocks Benedick's ineptitude as a soldier. Leonato explains, "There is a kind of merry war betwixt Signor Benedick and her."

On the soldiers' arrival, Don Pedro tells Leonato that they will stay a month at least, and Benedick and Beatrice resume their "merry war". Pedro's illegitimate brother, Don John, is also introduced. Claudio first lays eyes on Hero, and he informs Benedick of his intention to court her. Benedick, who openly despises marriage, tries to dissuade him. Don Pedro encourages the marriage. Benedick swears that he will never marry. Don Pedro laughs at him and tells him he will when he finds the right person.

A masquerade ball is planned. Therein a disguised Don Pedro woos Hero on Claudio's behalf. Don John uses this situation to sow chaos by telling Claudio that Don Pedro is wooing Hero for himself. Claudio rails against the entrapments of beauty. But the misunderstanding is later resolved, and Claudio is promised Hero's hand in marriage.

Meanwhile, Benedick and Beatrice have danced together, trading disparaging remarks under the cover of their masks. Beatrice knows who Benedick is under his mask, but Benedick does not recognize the mystery lady. Benedick is stung at hearing himself described as "the prince's jester, a very dull fool", and yearns to be spared the company of "Lady Tongue". Don Pedro and his men, bored at the prospect of waiting a week for the wedding, concoct a plan to match-make between Benedick and Beatrice. They arrange for Benedick to overhear a conversation in which they declare that Beatrice is madly in love with him but too afraid to tell him. Hero and Ursula likewise ensure that Beatrice overhears a conversation in which they discuss Benedick's undying love for her. Both Benedick and Beatrice are delighted to think that they are the object of unrequited love, and both resolve to mend their faults and declare their love.

Meanwhile, Don John plots to stop the wedding, embarrass his brother, and wreak misery on Leonato and Claudio. He tells Don Pedro and Claudio that Hero is "disloyal", and arranges for them to see his associate, Borachio, enter her bedchamber and engage amorously with her (it is actually Hero's chambermaid). Claudio and Don Pedro are duped, and Claudio vows to humiliate Hero publicly.

The next day, at the wedding, Claudio denounces Hero before the stunned guests and storms off with Don Pedro. Hero faints. A humiliated Leonato expresses his wish for her to die. The presiding friar intervenes, believing Hero innocent. He suggests that the family fake Hero's death to fill Claudio with remorse. Prompted by the stressful events, Benedick and Beatrice confess their love for each other. Beatrice then asks Benedick to kill Claudio as proof of his devotion. Benedick hesitates but is swayed. Leonato and Antonio blame Claudio for Hero's supposed death and threaten him, to little effect. Benedick arrives and challenges him to a duel.

On the night of Don John's treachery, the local Watch overheard Borachio and Conrade discussing their "treason" and "most dangerous piece of lechery that ever was known in the commonwealth", and arrested them therefore. Despite their ineptitude (headed by constable Dogberry), they obtain a confession and inform Leonato of Hero's innocence. Don John has fled, but a force is sent to capture him. Remorseful and thinking Hero dead, Claudio agrees to her father's demand that he marry Antonio's daughter, "almost the copy of my child that's dead".

After Claudio swears to marry this other bride, she is revealed to be Hero. Claudio is overjoyed. Beatrice and Benedick publicly confess their love for each other. Don Pedro taunts "Benedick the married man", and Benedick counters that he finds the Prince sad, advising him: "Get thee a wife". As the play draws to a close, a messenger arrives with news of Don John's capture, but Benedick proposes to postpone deciding Don John's punishment until tomorrow so that the couples can enjoy their newfound happiness. The couples dance and celebrate as the play ends.

Sources

Shakespeare's immediate source may have been one of Matteo Bandello of Mantua's Novelle ("Tales"), possibly the translation into French by François de Belleforest,[6] which dealt with the tribulations of Sir Timbreo and his betrothed Fenicia Lionata, in Messina, after Peter III of Aragon's defeat of Charles of Anjou. Another version, featuring lovers Ariodante and Ginevra, with the servant Dalinda impersonating Ginevra on the balcony, appears in Book V Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso (published in an English translation in 1591). The character of Benedick has a counterpart in a commentary on marriage in Orlando Furioso. But the witty wooing of Beatrice and Benedick is apparently original and very unusual in style and syncopation. Edmund Spenser tells one version of the Claudio–Hero plot in The Faerie Queene (Book II, Canto iv).

Date and text

According to the earliest printed text, Much Ado About Nothing was "sundry times publicly acted" before 1600. The play likely debuted in the autumn or winter of 1598–99. The earliest recorded performances are two at Court in the winter of 1612–13, during festivities preceding the Wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick V of the Palatinate (14 February 1613). In 1600, the stationers Andrew Wise and William Aspley published the play in quarto. This was the only edition prior to the First Folio in 1623.

Analysis and criticism

Style

The play is predominantly written in prose. The substantial verse sections achieve a sense of decorum.

Setting

Much Ado About Nothing is set in Messina, a port city on the island of Sicily, when Sicily is ruled by Aragon. Its action takes place mainly at the home and grounds of Leonato's Estate.

Themes and motifs

Gender roles

Benedick and Beatrice quickly became the main interest of the play. They are considered the leading roles even though their relationship is given equal or lesser weight in the script than Claudio's and Hero's situation. Charles I wrote, 'Benedick and Beatrice' beside the title of the play in his copy of the Second Folio. The provocative treatment of gender is central and should be considered in its Renaissance context. This was reflected and emphasized in certain plays of the period but was also challenged. Amussen notes that the undoing of traditional gender clichés seems to have inflamed anxieties about the erosion of social order. It seems that comic drama could be a means of calming such anxieties. Ironically, the play's popularity suggests that this only increased interest in such behavior. Benedick wittily gives voice to male anxieties about women's "sharp tongues and proneness to sexual lightness". In the play's patriarchal society, the men's loyalties are governed by conventional codes of honour, camaraderie, and a sense of superiority over women. Assumptions that women are by nature prone to inconstancy are shown in the repeated jokes about cuckoldry, and partly explain Claudio's readiness to believe the slander against Hero. This stereotype is turned on its head in Balthasar's song "Sigh No More", which presents men as the deceitful and inconstant sex that women must abide.

Infidelity

Several characters seem obsessed with the idea that a man cannot know whether his wife is faithful and that women can take full advantage of this. Don John plays upon Claudio's pride and fear of cuckoldry, leading to the disastrous first wedding. Many of the men readily believe that Hero is impure; even her father condemns her with very little evidence. This motif runs through the play, often referring to horns (a symbol of cuckoldry).

In contrast, Balthasar's song "Sigh No More" tells women to accept men's infidelity and continue to live joyfully. Some interpretations say that Balthasar sings poorly, undercutting the message. This is supported by Benedick's cynical comments about the song, comparing it to a howling dog. In Kenneth Branagh's 1993 film, Balthasar sings it beautifully: it is given a prominent role in the opening and finale, and the women seem to embrace its message.

Deception

The play has many examples of deception and self-deception. The games and tricks played on people often have the best intentions: to make people fall in love, to help someone get what they want, or to lead someone to realize their mistake. But not all are well-meant: Don John convinces Claudio that Don Pedro wants Hero for himself, and Borachio meets 'Hero' (actually Margaret) in Hero's bedroom window. These modes of deceit play into a complementary theme of emotional manipulation, the ease with which the characters' sentiments are redirected and their propensities exploited as a means to an end. The characters' feelings for each other are played as vehicles to reach the goal of engagement rather than as an end in themselves.

Masks and mistaken identity

Characters are constantly pretending to be others or mistaken for others. Margaret is mistaken for Hero, leading to Hero's disgrace. During a masked ball (in which everyone must wear a mask), Beatrice rants about Benedick to a masked man who is actually Benedick, but she acts unaware of this. During the same celebration, Don Pedro pretends to be Claudio and courts Hero for him. After Hero is proclaimed dead, Leonato orders Claudio to marry his 'niece', who is actually Hero.

Nothing

Another motif is the play on the words nothing and noting. These were near-homophones in Shakespeare's day. Taken literally, the title implies that a great fuss ('much ado') is made of something insignificant ('nothing'), such as the unfounded claims of Hero's infidelity and that Benedick and Beatrice are in love with each other. Nothing is also a double entendre: 'an O-thing' (or 'n othing' or 'no thing') was Elizabethan slang for "vagina", derived from women having 'nothing' between their legs. The title can also be understood as Much Ado About Noting: much of the action centres on interest in others and the critique of others, written messages, spying, and eavesdropping. This attention is mentioned several times directly, particularly concerning 'seeming', 'fashion', and outward impressions.

Examples of noting as noticing occur in the following instances: (1.1.131–132)

Claudio: Benedick, didst thou note the daughter of Signor Leonato?

Benedick: I noted her not, but I looked on her.

and (4.1.154–157).

Friar: Hear me a little,

For I have only been silent so long

And given way unto this course of fortune

By noting of the lady.

At (3.3.102–104), Borachio indicates that a man's clothing doesn't reveal his character:

Borachio: Thou knowest that the fashion of a doublet, or a hat, or a cloak is nothing to a man.

A triple play on words in which noting signifies noticing, musical notes, and nothing, occurs at (2.3.47–52):

Don Pedro: Nay pray thee, come;

Or if thou wilt hold longer argument,

Do it in notes.

Balthasar: Note this before my notes:

There's not a note of mine that's worth the noting.

Don Pedro: Why, these are very crotchets that he speaks –

Note notes, forsooth, and nothing!

Don Pedro's last line can be understood to mean 'Pay attention to your music and nothing else!' The complex layers of meaning include a pun on 'crotchets', which can mean both 'quarter notes' (in music) and whimsical notions.

The following are puns on notes as messages: (2.1.174–176),

Claudio: I pray you leave me.

Benedick: Ho, now you strike like the blind man – 'twas the boy that stole your meat, and you'll beat the post.

in which Benedick plays on the word post as a pole and as mail delivery in a joke reminiscent of Shakespeare's earlier advice 'Don't shoot the messenger'; and (2.3.138–142)

Claudio: Now you talk of a sheet of paper, I remember a pretty jest your daughter told us of.

Leonato: O, when she had writ it and was reading it over, she found Benedick and Beatrice between the sheet?

in which Leonato makes a sexual innuendo, concerning sheet as a sheet of paper (on which Beatrice's love note to Benedick is to have been written), and a bedsheet.

William Davenant staged The Law Against Lovers (1662), which inserted Beatrice and Benedick into an adaptation of Measure for Measure. Another adaptation, The Universal Passion, combined Much Ado with a play by Molière (1737). John Rich had revived Shakespeare's text at Lincoln's Inn Fields (1721). David Garrick first played Benedick in 1748 and continued to play him until 1776.

In 1836, Helena Faucit played Beatrice at the very beginning of her career at Covent Garden, opposite Charles Kemble as Benedick in his farewell performances. The great 19th-century stage team Henry Irving and Ellen Terry counted Benedick and Beatrice as their greatest triumph. John Gielgud made Benedick one of his signature roles between 1931 and 1959, playing opposite Diana Wynyard, Peggy Ashcroft, and Margaret Leighton. The longest-running Broadway production is A. J. Antoon's 1972 staging, starring Sam Waterston, Kathleen Widdoes, and Barnard Hughes. Derek Jacobi won a Tony Award for playing Benedick in 1984. Jacobi had also played Benedick in the Royal Shakespeare Company's highly praised 1982 production, with Sinéad Cusack playing Beatrice. Director Terry Hands produced the play on a stage-length mirror against an unchanging backdrop of painted trees. In 2013, Vanessa Redgrave and James Earl Jones (then in their seventies and eighties, respectively) played Beatrice and Benedick onstage at The Old Vic, London.

Actors, theatres, and awards

- c. 1598: In the original production by the Lord Chamberlain's Men, William Kempe played Dogberry and Richard Cowley played Verges.

- 1613: Wedding festivities of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick V of the Palatinate.

- 1748: David Garrick played Benedick for the first time.

- 1836: Helena Faucit and Charles Kemble as Beatrice and Benedick, Covent Garden.

- 1882: Henry Irving and Ellen Terry played Benedick and Beatrice at the Lyceum Theatre.

- 1931: John Gielgud played Benedick for the first time at the Old Vic Theatre, and it stayed in his repertory until 1959.

- 1960: A Tony Award Nomination for "Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play" went to Margaret Leighton for her role played in Much Ado.

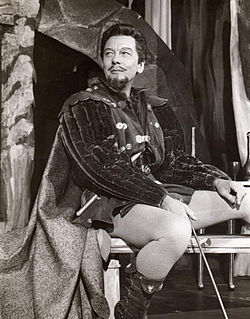

- 1965: A National Theatre production directed by Franco Zeffirelli with Maggie Smith, Robert Stephens, Ian McKellen, Lynn Redgrave, Albert Finney, Michael York and Derek Jacobi among others

- 1965: A Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word or Drama Recording nomination went to a recording of a National Theatre production with Maggie Smith and Robert Stephens

- 1973: A Tony Award Nomination for "Best Featured Actor in a Play" went to Barnard Hughes as Dogberry in the New York Shakespeare Festival production.

- 1973: A Tony Award Nomination for "Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play" went to Kathleen Widdoes.

- 1980: Sinéad Cusack and Derek Jacobi in a Royal Shakespeare Company production directed by Terry Hands.

- 1983: The Evening Standard Award for the "Best Actor" went to Derek Jacobi.

- 1985: A Tony Award Nomination for "Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play" was received by Sinéad Cusack.

- 1985: The Tony Award for "Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play" went to Derek Jacobi as Benedick.

- 1987: Tandy Cronyn as Beatrice and Richard Monette as Benedick in a production at the Stratford Festival directed by Peter Moss

- 1989: The Evening Standard Award for "Best Actress" went to Felicity Kendal as Beatrice in Elijah Moshinsky's production at the Strand Theatre.

- 1994: The Laurence Olivier Award for "Best Actor" went to Mark Rylance as Benedick in Matthew Warchus' production at the Queen's Theatre.

- 2006: The Laurence Olivier Award for "Best Actress" was received by Tamsin Greig as Beatrice in the Royal Shakespeare Company's production in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, directed by Marianne Elliott.

- 2007: Zoë Wanamaker appeared as Beatrice and Simon Russell Beale as Benedick in a National Theatre production directed by Nicholas Hytner.

- 2011: Eve Best appeared as Beatrice and Charles Edwards as Benedick at Shakespeare's Globe, directed by Jeremy Herrin.

The official poster for the 2011 production starring David Tennant and Catherine Tate - 2011: David Tennant as Benedick alongside Catherine Tate as Beatrice in a production of the play at the Wyndham's Theatre, directed by Josie Rourke. An authorized recording of this production is available to download and watch from Digital Theatre.

- 2012: Meera Syal as Beatrice and Paul Bhattacharjee as Benedick in an Indian setting, directed by Iqbal Khan for the Royal Shakespeare Company, part of the World Shakespeare Festival.

- 2013: Vanessa Redgrave as Beatrice and James Earl Jones as Benedick in a production at The Old Vic directed by Mark Rylance.

- 2013: A German-language production (Viel Lärm um Nichts), translated and directed by Marius von Mayenburg at the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, Berlin.

- 2017: Beatriz Romilly as Beatrice and Matthew Needham as Benedick in a Mexican setting, at Shakespeare's Globe, directed by Matthew Dunster.

- 2018: Mel Giedroyc as Beatrice and John Hopkins as Benedick in a modern Sicilian setting, at the Rose Theatre, Kingston, directed by Simon Dormandy.

- 2019: Danielle Brooks as Beatrice and Grantham Coleman as Benedick with an all-Black cast set in contemporary Georgia, at The Public Theater, directed by Kenny Leon. This version was broadcast on PBS Great Performances on 22 November 2019.

- 2022: Jennifer Paredes as Hero and Gerrard James as Claudio at Denver Center for the Performing Arts.

- 2023: Maev Beaty as Beatrice and Graham Abbey as Benedick in a production at the Stratford Festival directed by Chris Abraham.

- 2025: Hayley Atwell as Beatrice and Tom Hiddleston as Benedick at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane directed by Jamie Lloyd.

Adaptations

Music

The operas Montano et Stéphanie (1799) by Jean-Élie Bédéno Dejaure and Henri-Montan Berton, Béatrice et Bénédict (1862) by Hector Berlioz, Beaucoup de bruit pour rien (pub. 1898) by Paul Puget, Viel Lärm um Nichts (1896) by Árpád Doppler, and Much Ado About Nothing by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1901) are based upon the play.

The composer Edward MacDowell said he was inspired by Ellen Terry's portrayal of Beatrice in this play for the scherzo of his Piano Concerto No. 2.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold composed music for a 1917 production at the Vienna Burgtheater by Max Reinhardt.

In 2006 the American Music Theatre Project produced The Boys Are Coming Home, a musical adaptation by Berni Stapleton and Leslie Arden that sets Much Ado About Nothing in America during the Second World War.

The title track of the 2009 Mumford & Sons album Sigh No More uses quotes from this play in the song. The title of the album is also a quotation from Act 2 Scene 3 of the play.

A 2015 rock opera adaptation of the play, These Paper Bullets, was written by Rolin Jones with music by Billie Joe Armstrong.

Opera McGill have commissioned an opera based on the play, with music by James Garner and libretto adapted by Patrick Hansen.

Film

The first cinematic version in English may have been the 1913 silent film directed by Phillips Smalley.

Martin Hellberg's 1964 East German film Viel Lärm um nichts was based on the play. In 1973 a Soviet film adaptation was directed by Samson Samsonov, starring Galina Jovovich and Konstantin Raikin.

A version of the 1967 National Theatre Company Production, directed for television by Alan Cooke. The play was originally directed for the stage by Franco Zeffirelli. With Maggie Smith (Beatrice), Derek Jacobi (Don Pedro). Music by Nino Rota

The first sound version in English released to cinemas was the 1993 film by Kenneth Branagh. It starred Branagh as Benedick, Branagh's then-wife Emma Thompson as Beatrice, Denzel Washington as Don Pedro, Keanu Reeves as Don John, Richard Briers as Leonato, Michael Keaton as Dogberry, Robert Sean Leonard as Claudio, Imelda Staunton as Margaret, and Kate Beckinsale in her film debut as Hero.

The 2001 Hindi film Dil Chahta Hai is a loose adaptation of the play.

In 2011, Joss Whedon completed filming an adaptation, which was released in June 2013. The cast includes Amy Acker as Beatrice, Alexis Denisof as Benedick, Nathan Fillion as Dogberry, Clark Gregg as Leonato, Reed Diamond as Don Pedro, Fran Kranz as Claudio, Jillian Morgese as Hero, Sean Maher as Don John, Spencer Treat Clark as Borachio, Riki Lindhome as Conrade, Ashley Johnson as Margaret, Tom Lenk as Verges, and Romy Rosemont as the sexton. Whedon's adaptation is a contemporary revision with an Italian-mafia theme.

In 2012 a filmed version of the live 2011 performance at The Globe was released to cinemas and on DVD. The same year, a filmed version of the 2011 performance at Wyndham's Theatre was made available for download or streaming on the Digital Theatre website.

In 2015, Owen Drake created a modern movie version of the play, Messina High, starring Faye Reagan.

The 2023 romantic comedy Anyone but You, directed by Will Gluck and co-written by Ilana Wolpert, is a loose adaptation principally set in contemporary Australia. It stars Sydney Sweeney and Glen Powell as analogues of Beatrice and Benedick.

Television and web series

The 1973 New York Shakespeare Festival production by Joseph Papp, shot on videotape and released on VHS and DVD, includes more of the text than Branagh's version. It is directed by A. J. Antoon and stars Sam Waterston, Kathleen Widdoes, and Barnard Hughes.

The 1984 BBC Television version stars Lee Montague as Leonato, Cherie Lunghi as Beatrice, Katharine Levy as Hero, Jon Finch as Don Pedro, Robert Lindsay as Benedick, Robert Reynolds as Claudio, Gordon Whiting as Antonio and Vernon Dobtcheff as Don John. An earlier BBC television version with Maggie Smith and Robert Stephens, adapted from Franco Zeffirelli's stage production for the National Theatre Company's London stage production, was broadcast in February 1967.

In 2005, the BBC adapted the story as part of the ShakespeaRe-Told season. This version is set in the modern-day studios of Wessex Tonight, a fictional regional news programme. The cast includes Damian Lewis, Sarah Parish, and Billie Piper.

The 2014 YouTube web series Nothing Much to Do is a modern retelling of the play set in New Zealand.

In 2019, PBS recorded a live production of the Public Theater's 2019 Shakespeare in the Park production at the Delacorte Theater in New York City's Central Park for Great Performances. The all-Black cast features Danielle Brooks and Grantham Coleman as Beatrice and Benedick, with Chuck Cooper as Leonato. It was directed by Kenny Leon, with choreography by Camille A. Brown.

Young adult fiction

There are several young adult novels adapting Much Ado About Nothing. Lily Anderson's 2016 novel The Only Thing Worse Than Me Is You is about Trixie Watson and Ben West, who attend a "school for geniuses". In Speak Easy, Speak Love (2017) by Mckelle George, the play's events take place in the 1920s; it is focused around a failing speakeasy. In Nothing Happened (2018) by Molly Booth, Claudio and Hero are a queer couple, Claudia and Hana. Under a Dancing Star (2019) by Laura Wood is a modernized version set in Florence. Two Wrongs Make a Right (2022) by Chloe Liese is another contemporary version.

Citations

In his text on Jonathan Swift from 1940, Johannes V. Jensen cited Don John's line

I am trusted with a muzzle and enfranchised with a clog; therefore I have decreed not to sing in my cage. If I had my mouth, I would bite; if I had my liberty, I would do my liking: in the meantime let me be that I am and seek not to alter me.

Jensen later explained that this was a reference to the censorship imposed after the German invasion of Denmark in 1940.