A Markov chain is "a stochastic model describing a sequence of possible events in which the probability of each event depends only on the state attained in the previous event".[1]

In probability theory and related fields, a Markov process, named after the Russian mathematician Andrey Markov, is a stochastic process that satisfies the Markov property[2][3] (sometimes characterized as "memorylessness"). Roughly speaking, a process satisfies the Markov property if one can make predictions for the future of the process based solely on its present state just as well as one could knowing the process's full history, hence independently from such history; i.e., conditional on the present state of the system, its future and past states are independent.

A Markov chain is a type of Markov process that has either discrete state space or discrete index set (often representing time), but the precise definition of a Markov chain varies.[4] For example, it is common to define a Markov chain as a Markov process in either discrete or continuous time with a countable state space (thus regardless of the nature of time),[5][6][7][8] but it is also common to define a Markov chain as having discrete time in either countable or continuous state space (thus regardless of the state space).[4]

Markov studied Markov processes in the early 20th century, publishing his first paper on the topic in 1906.[9][10][11] Random walks on integers and the gambler's ruin problem are examples of Markov processes.[12][13] Some variations of these processes were studied hundreds of years earlier in the context of independent variables.[14][15] Two important examples of Markov processes are the Wiener process, also known as the Brownian motion process, and the Poisson process,[16] which are considered the most important and central stochastic processes in the theory of stochastic processes,[17][18][19] and were discovered repeatedly and independently, both before and after 1906, in various settings.[20][21] These two processes are Markov processes in continuous time, while random walks on the integers and the gambler's ruin problem are examples of Markov processes in discrete time.[12][13]

Markov chains have many applications as statistical models of real-world processes,[22][23][24] such as studying cruise control systems in motor vehicles, queues or lines of customers arriving at an airport, exchange rates of currencies, storage systems such as dams, and population growths of certain animal species.[25] The algorithm known as PageRank, which was originally proposed for the internet search engine Google, is based on a Markov process.[26][27] Furthermore, Markov processes are the basis for general stochastic simulation methods known as Gibbs sampling and Markov Chain Monte Carlo, are used for simulating random objects with specific probability distributions, and have found extensive application in Bayesian statistics.[25][28][29]

The adjective Markovian is used to describe something that is related to a Markov process.[30]

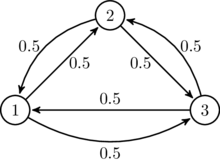

A diagram representing a two-state Markov process, with the states

labelled E and A. Each number represents the probability of the Markov

process changing from one state to another state, with the direction

indicated by the arrow. For example, if the Markov process is in state

A, then the probability it changes to state E is 0.4, while the

probability it remains in state A is 0.6.

Introduction

Russian mathematician Andrey Markov.

A Markov chain is a stochastic process with the Markov property. The term "Markov chain" refers to the sequence of random variables such a process moves through, with the Markov property defining serial dependence only between adjacent periods (as in a "chain"). It can thus be used for describing systems that follow a chain of linked events, where what happens next depends only on the current state of the system.

The system's state space and time parameter index need to be specified. The following table gives an overview of the different instances of Markov processes for different levels of state space generality and for discrete time v. continuous time:

| Countable state space | Continuous or general state space | |

|---|---|---|

| Discrete-time | (discrete-time) Markov chain on a countable or finite state space | Harris chain (Markov chain on a general state space) |

| Continuous-time | Continuous-time Markov process or Markov jump process | Any continuous stochastic process with the Markov property, e.g., the Wiener process |

Note that there is no definitive agreement in the literature on the use of some of the terms that signify special cases of Markov processes. Usually the term "Markov chain" is reserved for a process with a discrete set of times, i.e. a discrete-time Markov chain (DTMC),[31][31] but a few authors use the term "Markov process" to refer to a continuous-time Markov chain (CTMC) without explicit mention.[32][33][34] In addition, there are other extensions of Markov processes that are referred to as such but do not necessarily fall within any of these four categories (see Markov model). Moreover, the time index need not necessarily be real-valued; like with the state space, there are conceivable processes that move through index sets with other mathematical constructs. Notice that the general state space continuous-time Markov chain is general to such a degree that it has no designated term.

While the time parameter is usually discrete, the state space of a Markov chain does not have any generally agreed-on restrictions: the term may refer to a process on an arbitrary state space.[35] However, many applications of Markov chains employ finite or countably infinite state spaces, which have a more straightforward statistical analysis. Besides time-index and state-space parameters, there are many other variations, extensions and generalizations (see Variations). For simplicity, most of this article concentrates on the discrete-time, discrete state-space case, unless mentioned otherwise.

The changes of state of the system are called transitions. The probabilities associated with various state changes are called transition probabilities. The process is characterized by a state space, a transition matrix describing the probabilities of particular transitions, and an initial state (or initial distribution) across the state space. By convention, we assume all possible states and transitions have been included in the definition of the process, so there is always a next state, and the process does not terminate.

A discrete-time random process involves a system which is in a certain state at each step, with the state changing randomly between steps. The steps are often thought of as moments in time, but they can equally well refer to physical distance or any other discrete measurement. Formally, the steps are the integers or natural numbers, and the random process is a mapping of these to states. The Markov property states that the conditional probability distribution for the system at the next step (and in fact at all future steps) depends only on the current state of the system, and not additionally on the state of the system at previous steps.

Since the system changes randomly, it is generally impossible to predict with certainty the state of a Markov chain at a given point in the future. However, the statistical properties of the system's future can be predicted. In many applications, it is these statistical properties that are important.

A famous Markov chain is the so-called "drunkard's walk", a random walk on the number line where, at each step, the position may change by +1 or −1 with equal probability. From any position there are two possible transitions, to the next or previous integer. The transition probabilities depend only on the current position, not on the manner in which the position was reached. For example, the transition probabilities from 5 to 4 and 5 to 6 are both 0.5, and all other transition probabilities from 5 are 0. These probabilities are independent of whether the system was previously in 4 or 6.

Another example is the dietary habits of a creature who eats only grapes, cheese, or lettuce, and whose dietary habits conform to the following rules:

- It eats exactly once a day.

- If it ate cheese today, tomorrow it will eat lettuce or grapes with equal probability.

- If it ate grapes today, tomorrow it will eat grapes with probability 1/10, cheese with probability 4/10 and lettuce with probability 5/10.

- If it ate lettuce today, tomorrow it will eat grapes with probability 4/10 or cheese with probability 6/10. It will not eat lettuce again tomorrow.

A series of independent events (for example, a series of coin flips) satisfies the formal definition of a Markov chain. However, the theory is usually applied only when the probability distribution of the next step depends non-trivially on the current state.

History

Andrey Markov studied Markov chains in the early 20th century. Markov was interested in studying an extension of independent random sequences, motivated by a disagreement with Pavel Nekrasov who claimed independence was necessary for the weak law of large numbers to hold.[36] In his first paper on Markov chains, published in 1906, Markov showed that under certain conditions the average outcomes of the Markov chain would converge to a fixed vector of values, so proving a weak law of large numbers without the independence assumption,[9][10][11] which had been commonly regarded as a requirement for such mathematical laws to hold.[11] Markov later used Markov chains to study the distribution of vowels in Eugene Onegin, written by Alexander Pushkin, and proved a central limit theorem for such chains.[9]In 1912 Poincaré studied Markov chains on finite groups with an aim to study card shuffling. Other early uses of Markov chains include a diffusion model, introduced by Paul and Tatyana Ehrenfest in 1907, and a branching process, introduced by Francis Galton and Henry William Watson in 1873, preceding the work of Markov.[9][10] After the work of Galton and Watson, it was later revealed that their branching process had been independently discovered and studied around three decades earlier by Irénée-Jules Bienaymé.[37] Starting in 1928, Maurice Fréchet became interested in Markov chains, eventually resulting in him publishing in 1938 a detailed study on Markov chains.[9][38]

Andrei Kolmogorov developed in a 1931 paper a large part of the early theory of continuous-time Markov processes.[39][40] Kolmogorov was partly inspired by Louis Bachelier's 1900 work on fluctuations in the stock market as well as Norbert Wiener's work on Einstein's model of Brownian movement.[39][41] He introduced and studied a particular set of Markov processes known as diffusion processes, where he derived a set of differential equations describing the processes. Independent of Kolmogorov's work, Sydney Chapman derived in a 1928 paper an equation, now called the Chapman–Kolmogorov equation, in a less mathematically rigorous way than Kolmogorov, while studying Brownian movement.[43] The differential equations are now called the Kolmogorov equations[44] or the Kolmogorov–Chapman equations.[45] Other mathematicians who contributed significantly to the foundations of Markov processes include William Feller, starting in 1930s, and then later Eugene Dynkin, starting in the 1950s.[40]

Examples

Gambling

Suppose that you start with $10, and you wager $1 on an unending, fair, coin toss indefinitely, or until you lose all of your money. If represents the number of dollars you have after n tosses, with

represents the number of dollars you have after n tosses, with  , then the sequence

, then the sequence  is a Markov process. If I know that you have $12 now, then it would be

expected that with even odds, you will either have $11 or $13 after the

next toss. This guess is not improved by the added knowledge that you

started with $10, then went up to $11, down to $10, up to $11, and then

to $12.

is a Markov process. If I know that you have $12 now, then it would be

expected that with even odds, you will either have $11 or $13 after the

next toss. This guess is not improved by the added knowledge that you

started with $10, then went up to $11, down to $10, up to $11, and then

to $12.

The process described here is a Markov chain on a countable state space that follows a random walk.

A birth-death process

If one pops one hundred kernels of popcorn in an oven, each kernel popping at an independent exponentially-distributed time, then this would be a continuous-time Markov process. If denotes the number of kernels which have popped up to time t,

the problem can be defined as finding the number of kernels that will

pop in some later time. The only thing one needs to know is the number

of kernels that have popped prior to the time "t". It is not necessary

to know when they popped, so knowing

denotes the number of kernels which have popped up to time t,

the problem can be defined as finding the number of kernels that will

pop in some later time. The only thing one needs to know is the number

of kernels that have popped prior to the time "t". It is not necessary

to know when they popped, so knowing  for previous times "t" is not relevant.

for previous times "t" is not relevant.

The process described here is an approximation of a Poisson point process - Poisson processes are also Markov processes.

A non-Markov example

Suppose that there is a coin purse containing five quarters (each worth 25¢), five dimes (each worth 10¢), and five nickels (each worth 5¢), and one-by-one, coins are randomly drawn from the purse and are set on a table. If represents the total value of the coins set on the table after n draws, with

represents the total value of the coins set on the table after n draws, with  , then the sequence

, then the sequence  is not a Markov process.

is not a Markov process.To see why this is the case, suppose that in the first six draws, all five nickels and a quarter are drawn. Thus

. If we know not just

. If we know not just  ,

but the earlier values as well, then we can determine which coins have

been drawn, and we know that the next coin will not be a nickel; so we

can determine that

,

but the earlier values as well, then we can determine which coins have

been drawn, and we know that the next coin will not be a nickel; so we

can determine that  with probability 1. But if we do not know the earlier values, then based only on the value

with probability 1. But if we do not know the earlier values, then based only on the value  we might guess that we had drawn four dimes and two nickels, in which

case it would certainly be possible to draw another nickel next. Thus,

our guesses about

we might guess that we had drawn four dimes and two nickels, in which

case it would certainly be possible to draw another nickel next. Thus,

our guesses about  are impacted by our knowledge of values prior to

are impacted by our knowledge of values prior to  .

.Markov property

Formal definition

Discrete-time Markov chain

A discrete-time Markov chain is a sequence of random variables X1, X2, X3, ... with the Markov property, namely that the probability of moving to the next state depends only on the present state and not on the previous states,

- if both conditional probabilities are well defined, i.e. if

-

.

Markov chains are often described by a sequence of directed graphs, where the edges of graph n are labeled by the probabilities of going from one state at time n to the other states at time n + 1,

. The same information is represented by the transition matrix from time n to time n + 1.

However, Markov chains are frequently assumed to be time-homogeneous

(see variations below), in which case the graph and matrix are

independent of n and are thus not presented as sequences.

. The same information is represented by the transition matrix from time n to time n + 1.

However, Markov chains are frequently assumed to be time-homogeneous

(see variations below), in which case the graph and matrix are

independent of n and are thus not presented as sequences.These descriptions highlight the structure of the Markov chain that is independent of the initial distribution

.

When time-homogeneous, the chain can be interpreted as a state machine

assigning a probability of hopping from each vertex or state to an

adjacent one. The probability

.

When time-homogeneous, the chain can be interpreted as a state machine

assigning a probability of hopping from each vertex or state to an

adjacent one. The probability  of the machine's state can be analyzed as the statistical behavior of the machine with an element

of the machine's state can be analyzed as the statistical behavior of the machine with an element  of the state space as input, or as the behavior of the machine with the initial distribution

of the state space as input, or as the behavior of the machine with the initial distribution ![\Pr(X_{1}=y)=[x_{1}=y]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f630bd6c1d1563504ad0817cfaa48a0ebe2be938) of states as input, where

of states as input, where ![[P]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/25d78ad4ad13872df07ac9b02a2574250a0e54fd) is the Iverson bracket.

is the Iverson bracket.The fact that some sequences of states might have zero probability of occurring corresponds to a graph with multiple connected components, where we omit edges that would carry a zero transition probability. For example, if a has a nonzero probability of going to b, but a and x lie in different connected components of the graph, then

is defined, while

is defined, while  is not.

is not.Variations

- Time-homogeneous Markov chains (or stationary Markov chains) are processes where

- for all n. The probability of the transition is independent of n.

- A Markov chain with memory (or a Markov chain of order m)

- In other words, the future state depends on the past m states. It is possible to construct a chain (Yn) from (Xn) which has the 'classical' Markov property by taking as state space the ordered m-tuples of X values, ie. Yn = (Xn, Xn−1, ..., Xn−m+1).

Example

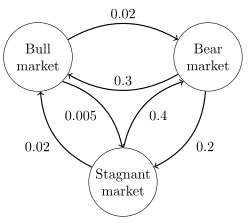

A state diagram for a simple example is shown in the figure on the right, using a directed graph to picture the state transitions. The states represent whether a hypothetical stock market is exhibiting a bull market, bear market, or stagnant market trend during a given week. According to the figure, a bull week is followed by another bull week 90% of the time, a bear week 7.5% of the time, and a stagnant week the other 2.5% of the time. Labelling the state space {1 = bull, 2 = bear, 3 = stagnant} the transition matrix for this example isA finite state machine can be used as a representation of a Markov chain. Assuming a sequence of independent and identically distributed input signals (for example, symbols from a binary alphabet chosen by coin tosses), if the machine is in state y at time n, then the probability that it moves to state x at time n + 1 depends only on the current state.

Continuous-time Markov chain

A continuous-time Markov chain (Xt)t ≥ 0 is defined by a finite or countable state space S, a transition rate matrix Q with dimensions equal to that of the state space and initial probability distribution defined on the state space. For i ≠ j, the elements qij are non-negative and describe the rate of the process transitions from state i to state j. The elements qii are chosen such that each row of the transition rate matrix sums to zero.There are three equivalent definitions of the process.[47]

Infinitesimal definition

The continuous time Markov chain is characterized by the transition

rates, the derivatives with respect to time of the transition

probabilities between states i and j.

Let Xt be the random variable describing the state of the process at time t, and assume that the process is in a state i at time t.

Then, knowing Xt = i, Xt + h is independent of previous values (Xs : s< t), and as h → 0 for all j and for all t:

,

,

using the little-o notation. The qij can be seen as measuring how quickly the transition from i to j happens.

Jump chain/holding time definition

Define a discrete-time Markov chain Yn to describe the nth jump of the process and variables S1, S2, S3, ... to describe holding times in each of the states where Si follows the exponential distribution with rate parameter −qYiYi.Transition probability definition

For any value n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ... and times indexed up to this value of n: t0, t1, t2, ... and all states recorded at these times i0, i1, i2, i3, ... it holds thatTransient evolution

The probability of going from state i to state j in n time steps isThe marginal distribution Pr(Xn = x) is the distribution over states at time n. The initial distribution is Pr(X0 = x). The evolution of the process through one time step is described by

Properties

Reducibility

A Markov chain is said to be irreducible if it is possible to get to any state from any state. The following explains this definition more formally.A state j is said to be accessible from a state i (written i → j) if a system started in state i has a non-zero probability of transitioning into state j at some point. Formally, state j is accessible from state i if there exists an integer nij ≥ 0 such that

A state i is said to communicate with state j (written i ↔ j) if both i → j and j → i. A communicating class is a maximal set of states C such that every pair of states in C communicates with each other. Communication is an equivalence relation, and communicating classes are the equivalence classes of this relation.

A communicating class is closed if the probability of leaving the class is zero, namely if i is in C but j is not, then j is not accessible from i. The set of communicating classes forms a directed, acyclic graph by inheriting the arrows from the original state space. A communicating class is closed if and only if it has no outgoing arrows in this graph.

A state i is said to be essential or final if for all j such that i → j it is also true that j → i. A state i is inessential if it is not essential.[48] A state is final if and only if its communicating class is closed.

A Markov chain is said to be irreducible if its state space is a single communicating class; in other words, if it is possible to get to any state from any state.

Periodicity

A state i has period k if any return to state i must occur in multiples of k time steps. Formally, the period of a state is defined asIf k = 1, then the state is said to be aperiodic. Otherwise (k > 1), the state is said to be periodic with period k. A Markov chain is aperiodic if every state is aperiodic. An irreducible Markov chain only needs one aperiodic state to imply all states are aperiodic.

Every state of a bipartite graph has an even period.

Transience and recurrence

A state i is said to be transient if, given that we start in state i, there is a non-zero probability that we will never return to i. Formally, let the random variable Ti be the first return time to state i (the "hitting time"):Mean recurrence time

Even if the hitting time is finite with probability 1, it need not have a finite expectation. The mean recurrence time at state i is the expected return time Mi:Expected number of visits

It can be shown that a state i is recurrent if and only if the expected number of visits to this state is infinite, i.e.,Absorbing states

A state i is called absorbing if it is impossible to leave this state. Therefore, the state i is absorbing if and only ifErgodicity

A state i is said to be ergodic if it is aperiodic and positive recurrent. In other words, a state i is ergodic if it is recurrent, has a period of 1, and has finite mean recurrence time. If all states in an irreducible Markov chain are ergodic, then the chain is said to be ergodic.It can be shown that a finite state irreducible Markov chain is ergodic if it has an aperiodic state. More generally, a Markov chain is ergodic if there is a number N such that any state can be reached from any other state in any number of steps greater than or equal to a number N. In case of a fully connected transition matrix, where all transitions have a non-zero probability, this condition is fulfilled with N = 1.

A Markov chain with more than one state and just one out-going transition per state is either not irreducible or not aperiodic, hence cannot be ergodic.

Steady-state analysis and limiting distributions

If the Markov chain is a time-homogeneous Markov chain, so that the process is described by a single, time-independent matrix , then the vector

, then the vector  is called a stationary distribution (or invariant measure) if

is called a stationary distribution (or invariant measure) if  it satisfies

it satisfies ) if and only if all of its states are positive recurrent.[49] In that case, π is unique and is related to the expected return time:

) if and only if all of its states are positive recurrent.[49] In that case, π is unique and is related to the expected return time: is the normalizing constant. Further, if the positive recurrent chain is both irreducible and aperiodic, it is said to have a limiting distribution; for any i and j,

is the normalizing constant. Further, if the positive recurrent chain is both irreducible and aperiodic, it is said to have a limiting distribution; for any i and j, is called the equilibrium distribution of the chain.

is called the equilibrium distribution of the chain.If a chain has more than one closed communicating class, its stationary distributions will not be unique (consider any closed communicating class

in the chain; each one will have its own unique stationary distribution

in the chain; each one will have its own unique stationary distribution  .

Extending these distributions to the overall chain, setting all values

to zero outside the communication class, yields that the set of

invariant measures of the original chain is the set of all convex

combinations of the

.

Extending these distributions to the overall chain, setting all values

to zero outside the communication class, yields that the set of

invariant measures of the original chain is the set of all convex

combinations of the  's). However, if a state j is aperiodic, then

's). However, if a state j is aperiodic, thenSteady-state analysis and the time-inhomogeneous Markov chain

A Markov chain need not necessarily be time-homogeneous to have an equilibrium distribution. If there is a probability distribution over states such that

such that is an equilibrium distribution of the Markov chain. Such can occur in Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

methods in situations where a number of different transition matrices

are used, because each is efficient for a particular kind of mixing, but

each matrix respects a shared equilibrium distribution.

is an equilibrium distribution of the Markov chain. Such can occur in Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

methods in situations where a number of different transition matrices

are used, because each is efficient for a particular kind of mixing, but

each matrix respects a shared equilibrium distribution.Finite state space

If the state space is finite, the transition probability distribution can be represented by a matrix, called the transition matrix, with the (i, j)th element of P equal toStationary distribution relation to eigenvectors and simplices

A stationary distribution π is a (row) vector, whose entries are non-negative and sum to 1, is unchanged by the operation of transition matrix P on it and so is defined by ) multiple of a left eigenvector e of the transition matrix PT with an eigenvalue

of 1. If there is more than one unit eigenvector then a weighted sum of

the corresponding stationary states is also a stationary state. But for

a Markov chain one is usually more interested in a stationary state

that is the limit of the sequence of distributions for some initial

distribution.

) multiple of a left eigenvector e of the transition matrix PT with an eigenvalue

of 1. If there is more than one unit eigenvector then a weighted sum of

the corresponding stationary states is also a stationary state. But for

a Markov chain one is usually more interested in a stationary state

that is the limit of the sequence of distributions for some initial

distribution.The values of a stationary distribution

are associated with the state space of P and its eigenvectors have their relative proportions preserved. Since the components of π are positive and the constraint that their sum is unity can be rewritten as

are associated with the state space of P and its eigenvectors have their relative proportions preserved. Since the components of π are positive and the constraint that their sum is unity can be rewritten as  we see that the dot product of π with a vector whose components are all 1 is unity and that π lies on a simplex.

we see that the dot product of π with a vector whose components are all 1 is unity and that π lies on a simplex.Time-homogeneous Markov chain with a finite state space

If the Markov chain is time-homogeneous, then the transition matrix P is the same after each step, so the k-step transition probability can be computed as the k-th power of the transition matrix, Pk.If the Markov chain is irreducible and aperiodic, then there is a unique stationary distribution π. Additionally, in this case Pk converges to a rank-one matrix in which each row is the stationary distribution π, that is,

is found, then the stationary distribution of the Markov chain in

question can be easily determined for any starting distribution, as will

be explained below.

is found, then the stationary distribution of the Markov chain in

question can be easily determined for any starting distribution, as will

be explained below.For some stochastic matrices P, the limit

does not exist while the stationary distribution does, as shown by this example:

does not exist while the stationary distribution does, as shown by this example:Because there are a number of different special cases to consider, the process of finding this limit if it exists can be a lengthy task. However, there are many techniques that can assist in finding this limit. Let P be an n×n matrix, and define

It is always true that

Here is one method for doing so: first, define the function f(A) to return the matrix A with its right-most column replaced with all 1's. If [f(P − In)]−1 exists then[50][citation needed]

- Explain: The original matrix equation is equivalent to a system of n×n linear equations in n×n variables. And there are n more linear equations from the fact that Q is a right stochastic matrix whose each row sums to 1. So it needs any n×n independent linear equations of the (n×n+n) equations to solve for the n×n variables. In this example, the n equations from “Q multiplied by the right-most column of (P-In)” have been replaced by the n stochastic ones.

Convergence speed to the stationary distribution

As stated earlier, from the equation (if exists) the stationary (or steady state) distribution π is a left eigenvector of row stochastic matrix P. Then assuming that P is diagonalizable or equivalently that P has n linearly independent eigenvectors, speed of convergence is elaborated as follows. (For non-diagonalizable, i.e. defective matrices, one may start with the Jordan normal form of P and proceed with a bit more involved set of arguments in a similar way.)

(if exists) the stationary (or steady state) distribution π is a left eigenvector of row stochastic matrix P. Then assuming that P is diagonalizable or equivalently that P has n linearly independent eigenvectors, speed of convergence is elaborated as follows. (For non-diagonalizable, i.e. defective matrices, one may start with the Jordan normal form of P and proceed with a bit more involved set of arguments in a similar way.)Let U be the matrix of eigenvectors (each normalized to having an L2 norm equal to 1) where each column is a left eigenvector of P and let Σ be the diagonal matrix of left eigenvalues of P, i.e. Σ = diag(λ1,λ2,λ3,...,λn). Then by eigendecomposition

we can write

we can write hence λ2/λ1 is the dominant term. Random noise in the state distribution π can also speed up this convergence to the stationary distribution.[52]

hence λ2/λ1 is the dominant term. Random noise in the state distribution π can also speed up this convergence to the stationary distribution.[52]Reversible Markov chain

A Markov chain is said to be reversible if there is a probability distribution π over its states such thatConsidering a fixed arbitrary time n and using the shorthand

As n was arbitrary, this reasoning holds for any n, and therefore for reversible Markov chains π is always a steady-state distribution of Pr(Xn+1 = j | Xn = i) for every n.

If the Markov chain begins in the steady-state distribution, i.e., if Pr(X0 = i) = πi, then Pr(Xn = i) = πi for all n and the detailed balance equation can be written as

Kolmogorov's criterion gives a necessary and sufficient condition for a Markov chain to be reversible directly from the transition matrix probabilities. The criterion requires that the products of probabilities around every closed loop are the same in both directions around the loop.

Reversible Markov chains are common in Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approaches because the detailed balance equation for a desired distribution π necessarily implies that the Markov chain has been constructed so that π is a steady-state distribution. Even with time-inhomogeneous Markov chains, where multiple transition matrices are used, if each such transition matrix exhibits detailed balance with the desired π distribution, this necessarily implies that π is a steady-state distribution of the Markov chain.

Closest reversible Markov chain

For any time-homogeneous Markov chain given by a transition matrix , any norm

, any norm  on

on  which is induced by a scalar product, and any probability vector

which is induced by a scalar product, and any probability vector  , there exists a unique transition matrix

, there exists a unique transition matrix  which is reversible according to

which is reversible according to  and which is closest to

and which is closest to  according to the norm

according to the norm  The matrix

The matrix  can be computed by solving a quadratic-convex optimization problem.[54] A GNU licensed Matlab script that computes the nearest reversible Markov chain can be found here.

can be computed by solving a quadratic-convex optimization problem.[54] A GNU licensed Matlab script that computes the nearest reversible Markov chain can be found here.For example, consider the following Markov chain:

This Markov chain is not reversible. According to the Frobenius Norm the closest reversible Markov chain according to

can be computed as

can be computed asIf we choose the probability vector randomly as

, then the closest reversible Markov chain according to the Frobenius norm is approximately given by

, then the closest reversible Markov chain according to the Frobenius norm is approximately given byBernoulli scheme

A Bernoulli scheme is a special case of a Markov chain where the transition probability matrix has identical rows, which means that the next state is even independent of the current state (in addition to being independent of the past states). A Bernoulli scheme with only two possible states is known as a Bernoulli process.General state space

For an overview of Markov chains on a general state space, see the article Markov chains on a measurable state space.Harris chains

Many results for Markov chains with finite state space can be generalized to chains with uncountable state space through Harris chains. The main idea is to see if there is a point in the state space that the chain hits with probability one. Generally, it is not true for continuous state space, however, we can define sets A and B along with a positive number ε and a probability measure ρ, such thatThe use of Markov chains in Markov chain Monte Carlo methods covers cases where the process follows a continuous state space.

Locally interacting Markov chains

Considering a collection of Markov chains whose evolution takes in account the state of other Markov chains, is related to the notion of locally interacting Markov chains. This corresponds to the situation when the state space has a (Cartesian-) product form. See interacting particle system and stochastic cellular automata (probabilistic cellular automata). See for instance Interaction of Markov Processes[55] or[56]Markovian representations

In some cases, apparently non-Markovian processes may still have Markovian representations, constructed by expanding the concept of the 'current' and 'future' states. For example, let X be a non-Markovian process. Then define a process Y, such that each state of Y represents a time-interval of states of X. Mathematically, this takes the form:An example of a non-Markovian process with a Markovian representation is an autoregressive time series of order greater than one.[57]

Transient behaviour

Write P(t) for the matrix with entries pij = P(Xt = j | X0 = i). Then the matrix P(t) satisfies the forward equation, a first-order differential equationStationary distribution

The stationary distribution for an irreducible recurrent CTMC is the probability distribution to which the process converges for large values of t. Observe that for the two-state process considered earlier with P(t) given byExample 1

Directed graph representation of a continuous-time Markov chain

describing the state of financial markets (note: numbers are made-up).

The image to the right describes a continuous-time Markov chain with state-space {Bull market, Bear market, Stagnant market} and transition rate matrix

Example 2

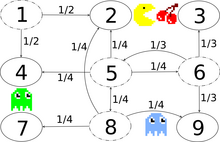

Transition graph with transition probabilities, exemplary for the states

1, 5, 6 and 8. There is a bidirectional secret passage between states 2

and 8.

The image to the right describes a discrete-time Markov chain with state-space {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9}. The player controls Pac-Man through a maze, eating pac-dots. Meanwhile, he is being hunted by ghosts. For convenience, the maze shall be a small 3x3-grid and the monsters move randomly in horizontal and vertical directions. A secret passageway between states 2 and 8 can be used in both directions. Entries with probability zero are removed in the following transition matrix:

This Markov chain is irreducible, because the ghosts can fly from every state to every state in a finite amount of time. Due to the secret passageway, the Markov chain is also aperiodic, because the monsters can move from any state to any state both in an even and in an uneven number of state transitions. Therefore, a unique stationary distribution exists and can be found by solving π Q = 0 subject to the constraint that elements must sum to 1. The solution of this linear equation subject to the constraint is

The central state and the border states 2 and 8 of the adjacent secret

passageway are visited most and the corner states are visited least.

The central state and the border states 2 and 8 of the adjacent secret

passageway are visited most and the corner states are visited least.Hitting times

The hitting time is the time, starting in a given set of states until the chain arrives in a given state or set of states. The distribution of such a time period has a phase type distribution. The simplest such distribution is that of a single exponentially distributed transition.Expected hitting times

For a subset of states A ⊆ S, the vector kA of hitting times (where element represents the expected value, starting in state i that the chain enters one of the states in the set A) is the minimal non-negative solution to[58]

represents the expected value, starting in state i that the chain enters one of the states in the set A) is the minimal non-negative solution to[58]Time reversal

For a CTMC Xt, the time-reversed process is defined to be . By Kelly's lemma this process has the same stationary distribution as the forward process.

. By Kelly's lemma this process has the same stationary distribution as the forward process.A chain is said to be reversible if the reversed process is the same as the forward process. Kolmogorov's criterion states that the necessary and sufficient condition for a process to be reversible is that the product of transition rates around a closed loop must be the same in both directions.

Embedded Markov chain

One method of finding the stationary probability distribution, π, of an ergodic continuous-time Markov chain, Q, is by first finding its embedded Markov chain (EMC). Strictly speaking, the EMC is a regular discrete-time Markov chain, sometimes referred to as a jump process. Each element of the one-step transition probability matrix of the EMC, S, is denoted by sij, and represents the conditional probability of transitioning from state i into state j. These conditional probabilities may be found byTo find the stationary probability distribution vector, we must next find

such that

such that being a row vector, such that all elements in

being a row vector, such that all elements in  are greater than 0 and

are greater than 0 and  = 1. From this, π may be found as

= 1. From this, π may be found asAnother discrete-time process that may be derived from a continuous-time Markov chain is a δ-skeleton—the (discrete-time) Markov chain formed by observing X(t) at intervals of δ units of time. The random variables X(0), X(δ), X(2δ), ... give the sequence of states visited by the δ-skeleton.

Applications

Research has reported the application and usefulness of Markov chains in a wide range of topics such as physics, chemistry, medicine, music, game theory and sports.Physics

Markovian systems appear extensively in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, whenever probabilities are used to represent unknown or unmodelled details of the system, if it can be assumed that the dynamics are time-invariant, and that no relevant history need be considered which is not already included in the state description.The paths, in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, are Markov chains.[60]

Markov chains are used in lattice QCD simulations.[61]

Chemistry

Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The enzyme (E) binds a substrate (S) and produces a product (P). Each reaction is a state transition in a Markov chain.

Markov chains and continuous-time Markov processes are useful in chemistry when physical systems closely approximate the Markov property. For example, imagine a large number n of molecules in solution in state A, each of which can undergo a chemical reaction to state B with a certain average rate. Perhaps the molecule is an enzyme, and the states refer to how it is folded. The state of any single enzyme follows a Markov chain, and since the molecules are essentially independent of each other, the number of molecules in state A or B at a time is n times the probability a given molecule is in that state.

The classical model of enzyme activity, Michaelis–Menten kinetics, can be viewed as a Markov chain, where at each time step the reaction proceeds in some direction. While Michaelis-Menten is fairly straightforward, far more complicated reaction networks can also be modeled with Markov chains.

An algorithm based on a Markov chain was also used to focus the fragment-based growth of chemicals in silico towards a desired class of compounds such as drugs or natural products.[62] As a molecule is grown, a fragment is selected from the nascent molecule as the "current" state. It is not aware of its past (i.e., it is not aware of what is already bonded to it). It then transitions to the next state when a fragment is attached to it. The transition probabilities are trained on databases of authentic classes of compounds.

Also, the growth (and composition) of copolymers may be modeled using Markov chains. Based on the reactivity ratios of the monomers that make up the growing polymer chain, the chain's composition may be calculated (e.g., whether monomers tend to add in alternating fashion or in long runs of the same monomer). Due to steric effects, second-order Markov effects may also play a role in the growth of some polymer chains.

Similarly, it has been suggested that the crystallization and growth of some epitaxial superlattice oxide materials can be accurately described by Markov chains.[63]

Testing

Several theorists have proposed the idea of the Markov chain statistical test (MCST), a method of conjoining Markov chains to form a "Markov blanket", arranging these chains in several recursive layers ("wafering") and producing more efficient test sets—samples—as a replacement for exhaustive testing. MCSTs also have uses in temporal state-based networks; Chilukuri et al.'s paper entitled "Temporal Uncertainty Reasoning Networks for Evidence Fusion with Applications to Object Detection and Tracking" (ScienceDirect) gives a background and case study for applying MCSTs to a wider range of applications.Speech recognition

Hidden Markov models are the basis for most modern automatic speech recognition systems.Information and computer science

Markov chains are used throughout information processing. Claude Shannon's famous 1948 paper A Mathematical Theory of Communication, which in a single step created the field of information theory, opens by introducing the concept of entropy through Markov modeling of the English language. Such idealized models can capture many of the statistical regularities of systems. Even without describing the full structure of the system perfectly, such signal models can make possible very effective data compression through entropy encoding techniques such as arithmetic coding. They also allow effective state estimation and pattern recognition. Markov chains also play an important role in reinforcement learning.Markov chains are also the basis for hidden Markov models, which are an important tool in such diverse fields as telephone networks (which use the Viterbi algorithm for error correction), speech recognition and bioinformatics (such as in rearrangements detection[64]).

The LZMA lossless data compression algorithm combines Markov chains with Lempel-Ziv compression to achieve very high compression ratios.

Queueing theory

Markov chains are the basis for the analytical treatment of queues (queueing theory). Agner Krarup Erlang initiated the subject in 1917.[65] This makes them critical for optimizing the performance of telecommunications networks, where messages must often compete for limited resources (such as bandwidth).[66]Numerous queueing models use continuous-time Markov chains. For example, an M/M/1 queue is a CTMC on the non-negative integers where upward transitions from i to i + 1 occur at rate λ according to a Poisson process and describe job arrivals, while transitions from i to i – 1 (for i > 1) occur at rate μ (job service times are exponentially distributed) and describe completed services (departures) from the queue.

Internet applications

The PageRank of a webpage as used by Google is defined by a Markov chain.[67] It is the probability to be at page in the stationary distribution on the following Markov chain on all (known) webpages. If

in the stationary distribution on the following Markov chain on all (known) webpages. If  is the number of known webpages, and a page

is the number of known webpages, and a page  has

has  links to it then it has transition probability

links to it then it has transition probability  for all pages that are linked to and

for all pages that are linked to and  for all pages that are not linked to. The parameter

for all pages that are not linked to. The parameter  is taken to be about 0.85.[68]

is taken to be about 0.85.[68]Markov models have also been used to analyze web navigation behavior of users. A user's web link transition on a particular website can be modeled using first- or second-order Markov models and can be used to make predictions regarding future navigation and to personalize the web page for an individual user.

Statistics

Markov chain methods have also become very important for generating sequences of random numbers to accurately reflect very complicated desired probability distributions, via a process called Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). In recent years this has revolutionized the practicability of Bayesian inference methods, allowing a wide range of posterior distributions to be simulated and their parameters found numerically.Economics and finance

Markov chains are used in finance and economics to model a variety of different phenomena, including asset prices and market crashes. The first financial model to use a Markov chain was from Prasad et al. in 1974.[dubious ][69] Another was the regime-switching model of James D. Hamilton (1989), in which a Markov chain is used to model switches between periods high and low GDP growth (or alternatively, economic expansions and recessions).[70] A more recent example is the Markov Switching Multifractal model of Laurent E. Calvet and Adlai J. Fisher, which builds upon the convenience of earlier regime-switching models.[71][72] It uses an arbitrarily large Markov chain to drive the level of volatility of asset returns.Dynamic macroeconomics heavily uses Markov chains. An example is using Markov chains to exogenously model prices of equity (stock) in a general equilibrium setting.[73]

Credit rating agencies produce annual tables of the transition probabilities for bonds of different credit ratings.[74]

Social sciences

Markov chains are generally used in describing path-dependent arguments, where current structural configurations condition future outcomes. An example is the reformulation of the idea, originally due to Karl Marx's Das Kapital, tying economic development to the rise of capitalism. In current research, it is common to use a Markov chain to model how once a country reaches a specific level of economic development, the configuration of structural factors, such as size of the middle class, the ratio of urban to rural residence, the rate of political mobilization, etc., will generate a higher probability of transitioning from authoritarian to democratic regime.[75]Mathematical biology

Markov chains also have many applications in biological modelling, particularly population processes, which are useful in modelling processes that are (at least) analogous to biological populations. The Leslie matrix, is one such example used to describe the population dynamics of many species, though some of its entries are not probabilities (they may be greater than 1). Another example is the modeling of cell shape in dividing sheets of epithelial cells.[76] Yet another example is the state of ion channels in cell membranes.Markov chains are also used in simulations of brain function, such as the simulation of the mammalian neocortex.[77] Markov chains have also been used to model viral infection of single cells.[78]

Genetics

Markov chains have been used in population genetics in order to describe the change in gene frequencies in small populations affected by genetic drift, for example in diffusion equation method described by Motoo Kimura.[79]Games

Markov chains can be used to model many games of chance. The children's games Snakes and Ladders and "Hi Ho! Cherry-O", for example, are represented exactly by Markov chains. At each turn, the player starts in a given state (on a given square) and from there has fixed odds of moving to certain other states (squares).Music

Markov chains are employed in algorithmic music composition, particularly in software such as CSound, Max and SuperCollider. In a first-order chain, the states of the system become note or pitch values, and a probability vector for each note is constructed, completing a transition probability matrix (see below). An algorithm is constructed to produce output note values based on the transition matrix weightings, which could be MIDI note values, frequency (Hz), or any other desirable metric.[80]| Note | A | C♯ | E♭ |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| C♯ | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.7 |

| E♭ | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Notes | A | D | G |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 0.18 | 0.6 | 0.22 |

| AD | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| AG | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.1 |

| DD | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| DA | 0.25 | 0 | 0.75 |

| DG | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 |

| GG | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| GA | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| GD | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Markov chains can be used structurally, as in Xenakis's Analogique A and B.[82] Markov chains are also used in systems which use a Markov model to react interactively to music input.[83]

Usually musical systems need to enforce specific control constraints on the finite-length sequences they generate, but control constraints are not compatible with Markov models, since they induce long-range dependencies that violate the Markov hypothesis of limited memory. In order to overcome this limitation, a new approach has been proposed.[84]

![{\displaystyle M_{i}=E[T_{i}]=\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }n\cdot f_{ii}^{(n)}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/40a59758d6b3e435f8b501e513653d1387277ae1)

![\mathbf {Q} =f(\mathbf {0} _{n,n})[f(\mathbf {P} -\mathbf {I} _{n})]^{-1}.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/23b90f245a33e8814743118543f81825ce084a5f)

![Y(t) = \big\{ X(s): s \in [a(t), b(t)] \, \big\}.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/09d6e381d59b76a48ff453d6a16129ba7f2fd239)