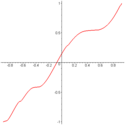

The slope field of  , showing three of the infinitely many solutions that can be produced by varying the arbitrary constant c.

, showing three of the infinitely many solutions that can be produced by varying the arbitrary constant c.

, showing three of the infinitely many solutions that can be produced by varying the arbitrary constant c.

, showing three of the infinitely many solutions that can be produced by varying the arbitrary constant c.In calculus, an antiderivative, primitive function, primitive integral or indefinite integral of a function f is a differentiable function F whose derivative is equal to the original function f. This can be stated symbolically as

. The process of solving for antiderivatives is called antidifferentiation (or indefinite integration) and its opposite operation is called differentiation, which is the process of finding a derivative.

. The process of solving for antiderivatives is called antidifferentiation (or indefinite integration) and its opposite operation is called differentiation, which is the process of finding a derivative.Antiderivatives are related to definite integrals through the fundamental theorem of calculus: the definite integral of a function over an interval is equal to the difference between the values of an antiderivative evaluated at the endpoints of the interval.

The discrete equivalent of the notion of antiderivative is antidifference.

Example

The function is an antiderivative of

is an antiderivative of  , as the derivative of

, as the derivative of  is

is  . As the derivative of a constant is zero,

. As the derivative of a constant is zero,  will have an infinite number of antiderivatives, such as

will have an infinite number of antiderivatives, such as  ,

,  ,

,  , etc. Thus, all the antiderivatives of

, etc. Thus, all the antiderivatives of  can be obtained by changing the value of c in

can be obtained by changing the value of c in  , where c is an arbitrary constant known as the constant of integration. Essentially, the graphs of antiderivatives of a given function are vertical translations of each other; each graph's vertical location depending upon the value c.

, where c is an arbitrary constant known as the constant of integration. Essentially, the graphs of antiderivatives of a given function are vertical translations of each other; each graph's vertical location depending upon the value c.In physics, the integration of acceleration yields velocity plus a constant. The constant is the initial velocity term that would be lost upon taking the derivative of velocity because the derivative of a constant term is zero. This same pattern applies to further integrations and derivatives of motion (position, velocity, acceleration, and so on).

Uses and properties

Antiderivatives can be used to compute definite integrals, using the fundamental theorem of calculus: if F is an antiderivative of the integrable function f over the interval![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) , then:

, then:

for all x. c is called the constant of integration. If the domain of F is a disjoint union of two or more (open) intervals, then a different constant of integration may be chosen for each of the intervals. For instance

for all x. c is called the constant of integration. If the domain of F is a disjoint union of two or more (open) intervals, then a different constant of integration may be chosen for each of the intervals. For instance

on its natural domain

on its natural domain

Every continuous function f has an antiderivative, and one antiderivative F is given by the definite integral of f with variable upper boundary:

There are many functions whose antiderivatives, even though they exist, cannot be expressed in terms of elementary functions (like polynomials, exponential functions, logarithms, trigonometric functions, inverse trigonometric functions and their combinations). Examples of these are

From left to right, the first four are the error function,

the Fresnel function, the trigonometric integral,

and the logarithmic integral function.

Techniques of integration

Finding antiderivatives of elementary functions is often considerably harder than finding their derivatives. For some elementary functions, it is impossible to find an antiderivative in terms of other elementary functions. See the articles on elementary functions and nonelementary integral for further information.There are various methods available:

- the linearity of integration allows us to break complicated integrals into simpler ones

- integration by substitution, often combined with trigonometric identities or the natural logarithm

- the inverse chain rule method, a special case of integration by substitution

- integration by parts to integrate products of functions

- Inverse function integration, a formula that expresses the antiderivative of the inverse

of an invertible and continuous function

in terms of the antiderivative of

and of

- the method of partial fractions in integration allows us to integrate all rational functions (fractions of two polynomials)

- the Risch algorithm

- when integrating multiple times, certain additional techniques can be used, see for instance double integrals and polar coordinates, the Jacobian and the Stokes' theorem

- if a function has no elementary antiderivative (for instance,

), its definite integral can be approximated using numerical integration

- it is often convenient to algebraically manipulate the integrand such that other integration techniques, such as integration by substitution, may be used.

- to calculate the (n times) repeated antiderivative of a function f, Cauchy's formula is useful:

Of non-continuous functions

Non-continuous functions can have antiderivatives. While there are still open questions in this area, it is known that:- Some highly pathological functions with large sets of discontinuities may nevertheless have antiderivatives.

- In some cases, the antiderivatives of such pathological functions may be found by Riemann integration, while in other cases these functions are not Riemann integrable.

- A necessary, but not sufficient, condition for a function f to have an antiderivative is that f have the intermediate value property. That is, if

is a subinterval of the domain of f and c is any real number between f(a) and f(b), then

for some c between a and b. This is a consequence of Darboux's theorem.

- The set of discontinuities of f must be a meagre set. This set must also be an F-sigma set (since the set of discontinuities of any function must be of this type). Moreover, for any meagre F-sigma set, one can construct some function f having an antiderivative, which has the given set as its set of discontinuities.

- If f has an antiderivative, is bounded on closed finite subintervals of the domain and has a set of discontinuities of Lebesgue measure 0, then an antiderivative may be found by integration in the sense of Lebesgue. In fact, using more powerful integrals like the Henstock–Kurzweil integral, every function for which an antiderivative exists is integrable, and its general integral coincides with its antiderivative.

- If f has an antiderivative F on a closed interval

, then for any choice of partition

, if one chooses sample points

as specified by the mean value theorem, then the corresponding Riemann sum telescopes to the value

.

- However if f is unbounded, or if f is bounded but the set of discontinuities of f has positive Lebesgue measure, a different choice of sample points

may give a significantly different value for the Riemann sum, no matter how fine the partition. See Example 4 below.

Some examples

- The function

withis not continuous at

but has the antiderivative

with. Since f is bounded on closed finite intervals and is only discontinuous at 0, the antiderivative F may be obtained by integration:

.

- The function

withis not continuous at

but has the antiderivative

with. Unlike Example 1, f(x) is unbounded in any interval containing 0, so the Riemann integral is undefined.

- If f(x) is the function in Example 1 and F is its antiderivative, and

is a dense countable subset of the open interval

, then the function

has an antiderivative

The set of discontinuities of g is precisely the set. Since g is bounded on closed finite intervals and the set of discontinuities has measure 0, the antiderivative G may be found by integration.

- Let

be a dense countable subset of the open interval

. Consider the everywhere continuous strictly increasing function

It can be shown that

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

for all values x where the series converges, and that the graph of F(x) has vertical tangent lines at all other values of x. In particular the graph has vertical tangent lines at all points in the set

.

.

Moreover

for all x where the derivative is defined. It follows that the inverse function

for all x where the derivative is defined. It follows that the inverse function  is differentiable everywhere and that

is differentiable everywhere and that

which is dense in the interval

which is dense in the interval ![\left[F\left(-1\right),F\left(1\right)\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d88b86159b2de44129d7b94b54e378bffa15a96d) . Thus g has an antiderivative G. On the other hand, it can not be true that

. Thus g has an antiderivative G. On the other hand, it can not be true that

![\left[F\left(-1\right),F\left(1\right)\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d88b86159b2de44129d7b94b54e378bffa15a96d) , one can choose sample points for the Riemann sum from the set

, one can choose sample points for the Riemann sum from the set  , giving a value of 0 for the sum. It follows that g has a set of discontinuities of positive Lebesgue measure. Figure 1 on the right shows an approximation to the graph of g(x) where

, giving a value of 0 for the sum. It follows that g has a set of discontinuities of positive Lebesgue measure. Figure 1 on the right shows an approximation to the graph of g(x) where  and the series is truncated to 8 terms. Figure 2 shows the graph of an approximation to the antiderivative G(x), also truncated to 8 terms. On the other hand if the Riemann integral is replaced by the Lebesgue integral, then Fatou's lemma or the dominated convergence theorem shows that g does satisfy the fundamental theorem of calculus in that context.

and the series is truncated to 8 terms. Figure 2 shows the graph of an approximation to the antiderivative G(x), also truncated to 8 terms. On the other hand if the Riemann integral is replaced by the Lebesgue integral, then Fatou's lemma or the dominated convergence theorem shows that g does satisfy the fundamental theorem of calculus in that context. . However, these examples can be easily modified so as to have sets of discontinuities which are dense on the entire real line

. However, these examples can be easily modified so as to have sets of discontinuities which are dense on the entire real line  . Let

. Let

has a dense set of discontinuities on

has a dense set of discontinuities on  and has antiderivative

and has antiderivative

![\left[a,b\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f30926fb280a9fdf66fd931e14d4363cb824feaa) is 0 whenever a and b are both rational, instead of

is 0 whenever a and b are both rational, instead of  .

. Thus the fundamental theorem of calculus will fail spectacularly.

![{\begin{aligned}\sum _{i=1}^{n}f(x_{i}^{*})(x_{i}-x_{i-1})&=\sum _{i=1}^{n}[F(x_{i})-F(x_{i-1})]\\&=F(x_{n})-F(x_{0})=F(b)-F(a)\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4321d3c55961ff5581fbbab0e33baeeef460cdd9)