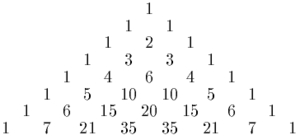

The binomial coefficients appear as the entries of Pascal's triangle where each entry is the sum of the two above it.

In elementary algebra, the binomial theorem (or binomial expansion) describes the algebraic expansion of powers of a binomial. According to the theorem, it is possible to expand the polynomial (x + y)n into a sum involving terms of the form a xb yc, where the exponents b and c are nonnegative integers with b + c = n, and the coefficient a of each term is a specific positive integer depending on n and b. For example (for n = 4),

or

or  (the two have the same value). These coefficients for varying n and b can be arranged to form Pascal's triangle. These numbers also arise in combinatorics, where

(the two have the same value). These coefficients for varying n and b can be arranged to form Pascal's triangle. These numbers also arise in combinatorics, where  gives the number of different combinations of b elements that can be chosen from an n-element set.

gives the number of different combinations of b elements that can be chosen from an n-element set.

History

Special cases of the binomial theorem were known since at least the 4th century B.C. when Greek mathematician Euclid mentioned the special case of the binomial theorem for exponent 2. There is evidence that the binomial theorem for cubes was known by the 6th century in India.Binomial coefficients, as combinatorial quantities expressing the number of ways of selecting k objects out of n without replacement, were of interest to the ancient Indian mathematicians. The earliest known reference to this combinatorial problem is the Chandaḥśāstra by the Indian lyricist Pingala (c. 200 B.C.), which contains a method for its solution. The commentator Halayudha from the 10th century A.D. explains this method using what is now known as Pascal's triangle. By the 6th century A.D., the Indian mathematicians probably knew how to express this as a quotient

, and a clear statement of this rule can be found in the 12th century text Lilavati by Bhaskara.

, and a clear statement of this rule can be found in the 12th century text Lilavati by Bhaskara.The first formulation of the binomial theorem and the table of binomial coefficients, to our knowledge, can be found in a work by Al-Karaji, quoted by Al-Samaw'al in his "al-Bahir". Al-Karaji described the triangular pattern of the binomial coefficients and also provided a mathematical proof of both the binomial theorem and Pascal's triangle, using an early form of mathematical induction. The Persian poet and mathematician Omar Khayyam was probably familiar with the formula to higher orders, although many of his mathematical works are lost. The binomial expansions of small degrees were known in the 13th century mathematical works of Yang Hui and also Chu Shih-Chieh. Yang Hui attributes the method to a much earlier 11th century text of Jia Xian, although those writings are now also lost.

In 1544, Michael Stifel introduced the term "binomial coefficient" and showed how to use them to express

in terms of

in terms of  , via "Pascal's triangle". Blaise Pascal studied the eponymous triangle comprehensively in the treatise Traité du triangle arithmétique

(1653). However, the pattern of numbers was already known to the

European mathematicians of the late Renaissance, including Stifel, Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia, and Simon Stevin.

, via "Pascal's triangle". Blaise Pascal studied the eponymous triangle comprehensively in the treatise Traité du triangle arithmétique

(1653). However, the pattern of numbers was already known to the

European mathematicians of the late Renaissance, including Stifel, Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia, and Simon Stevin.Isaac Newton is generally credited with the generalized binomial theorem, valid for any rational exponent.

Theorem statement

According to the theorem, it is possible to expand any power of x + y into a sum of the formwhere each

is a specific positive integer known as a binomial coefficient.

(When an exponent is zero, the corresponding power expression is taken

to be 1 and this multiplicative factor is often omitted from the term.

Hence one often sees the right side written as

is a specific positive integer known as a binomial coefficient.

(When an exponent is zero, the corresponding power expression is taken

to be 1 and this multiplicative factor is often omitted from the term.

Hence one often sees the right side written as  .) This formula is also referred to as the binomial formula or the binomial identity. Using summation notation, it can be written as

.) This formula is also referred to as the binomial formula or the binomial identity. Using summation notation, it can be written as

The final expression follows from the previous one by the symmetry of x and y in the first expression, and by comparison it follows that the sequence of binomial coefficients in the formula is symmetrical. A simple variant of the binomial formula is obtained by substituting 1 for y, so that it involves only a single variable. In this form, the formula reads

or equivalently

Examples

Pascal's triangle

The most basic example of the binomial theorem is the formula for the square of x + y:

The binomial coefficients 1, 2, 1 appearing in this expansion correspond to the second row of Pascal's triangle. (Note that the top "1" of the triangle is considered to be row 0, by convention.) The coefficients of higher powers of x + y correspond to lower rows of the triangle:

^{4}&=x^{4}+4x^{3}y+6x^{2}y^{2}+4xy^{3}+y^{4},\\[8pt](x+y)^{5}&=x^{5}+5x^{4}y+10x^{3}y^{2}+10x^{2}y^{3}+5xy^{4}+y^{5},\\[8pt](x+y)^{6}&=x^{6}+6x^{5}y+15x^{4}y^{2}+20x^{3}y^{3}+15x^{2}y^{4}+6xy^{5}+y^{6},\\[8pt](x+y)^{7}&=x^{7}+7x^{6}y+21x^{5}y^{2}+35x^{4}y^{3}+35x^{3}y^{4}+21x^{2}y^{5}+7xy^{6}+y^{7}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e30228a99653e6b9a65ae6640a3b7f85e2fdf144)

Several patterns can be observed from these examples. In general, for the expansion (x + y)n:

- the powers of x start at n and decrease by 1 in each term until they reach 0 (with x0 = 1, often unwritten);

- the powers of y start at 0 and increase by 1 until they reach n;

- the nth row of Pascal's Triangle will be the coefficients of the expanded binomial when the terms are arranged in this way;

- the number of terms in the expansion before like terms are combined is the sum of the coefficients and is equal to 2n; and

- there will be n + 1 terms in the expression after combining like terms in the expansion.

For a binomial involving subtraction, the theorem can be applied by using the form (x − y)n = (x + (−y))n. This has the effect of changing the sign of every other term in the expansion:

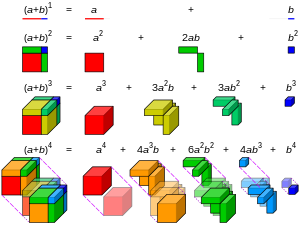

Geometric explanation

Visualisation of binomial expansion up to the 4th power

For positive values of a and b, the binomial theorem with n = 2 is the geometrically evident fact that a square of side a + b can be cut into a square of side a, a square of side b, and two rectangles with sides a and b. With n = 3, the theorem states that a cube of side a + b can be cut into a cube of side a, a cube of side b, three a×a×b rectangular boxes, and three a×b×b rectangular boxes.

In calculus, this picture also gives a geometric proof of the derivative

if one sets

if one sets  and

and  interpreting b as an infinitesimal change in a, then this picture shows the infinitesimal change in the volume of an n-dimensional hypercube,

interpreting b as an infinitesimal change in a, then this picture shows the infinitesimal change in the volume of an n-dimensional hypercube,  where the coefficient of the linear term (in

where the coefficient of the linear term (in  ) is

) is  the area of the n faces, each of dimension

the area of the n faces, each of dimension

and higher, become negligible, and yields the formula

and higher, become negligible, and yields the formula  interpreted as

interpreted as

- "the infinitesimal rate of change in volume of an n-cube as side length varies is the area of n of its

-dimensional faces".

– see proof of Cavalieri's quadrature formula for details.

– see proof of Cavalieri's quadrature formula for details.

Binomial coefficients

The coefficients that appear in the binomial expansion are called binomial coefficients. These are usually written , and pronounced “n choose k”.

, and pronounced “n choose k”.

Formulae

The coefficient of xn−kyk is given by the formulawith k factors in both the numerator and denominator of the fraction. Note that, although this formula involves a fraction, the binomial coefficient

is actually an integer.

is actually an integer.

Combinatorial interpretation

The binomial coefficient can be interpreted as the number of ways to choose k elements from an n-element set. This is related to binomials for the following reason: if we write (x + y)n as a product

can be interpreted as the number of ways to choose k elements from an n-element set. This is related to binomials for the following reason: if we write (x + y)n as a product

Proofs

Combinatorial proof

Example

The coefficient of xy2 in

equals

because there are three x,y strings of length 3 with exactly two y's, namely,

because there are three x,y strings of length 3 with exactly two y's, namely,

General case

Expanding (x + y)n yields the sum of the 2 n products of the form e1e2 ... e n where each e i is x or y. Rearranging factors shows that each product equals xn−kyk for some k between 0 and n. For a given k, the following are proved equal in succession:- the number of copies of xn − kyk in the expansion

- the number of n-character x,y strings having y in exactly k positions

- the number of k-element subsets of { 1, 2, ..., n}

(this is either by definition, or by a short combinatorial argument if one is defining

as

).

Inductive proof

Induction yields another proof of the binomial theorem. When n = 0, both sides equal 1, since x0 = 1 and .

Now suppose that the equality holds for a given n; we will prove it for n + 1.

For j, k ≥ 0, let [ƒ(x, y)] j,k denote the coefficient of xjyk in the polynomial ƒ(x, y).

By the inductive hypothesis, (x + y)n is a polynomial in x and y such that [(x + y)n] j,k is

.

Now suppose that the equality holds for a given n; we will prove it for n + 1.

For j, k ≥ 0, let [ƒ(x, y)] j,k denote the coefficient of xjyk in the polynomial ƒ(x, y).

By the inductive hypothesis, (x + y)n is a polynomial in x and y such that [(x + y)n] j,k is  if j + k = n, and 0 otherwise.

The identity

if j + k = n, and 0 otherwise.

The identity

Generalizations

Newton's generalized binomial theorem

Around 1665, Isaac Newton generalized the binomial theorem to allow real exponents other than nonnegative integers. (The same generalization also applies to complex exponents.) In this generalization, the finite sum is replaced by an infinite series. In order to do this, one needs to give meaning to binomial coefficients with an arbitrary upper index, which cannot be done using the usual formula with factorials. However, for an arbitrary number r, one can define is the Pochhammer symbol, here standing for a falling factorial. This agrees with the usual definitions when r is a nonnegative integer. Then, if x and y are real numbers with |x| greater than |y|, and r is any complex number, one has

is the Pochhammer symbol, here standing for a falling factorial. This agrees with the usual definitions when r is a nonnegative integer. Then, if x and y are real numbers with |x| greater than |y|, and r is any complex number, one has

When r is a nonnegative integer, the binomial coefficients for k > r are zero, so this equation reduces to the usual binomial theorem, and there are at most r + 1 nonzero terms. For other values of r, the series typically has infinitely many nonzero terms.

For example, r = 1/2 gives the following series for the square root:

Taking

, the generalized binomial series gives the geometric series formula, valid for

, the generalized binomial series gives the geometric series formula, valid for  :

:

More generally, with r = −s:

So, for instance, when

,

,

Further generalizations

The generalized binomial theorem can be extended to the case where x and y are complex numbers. For this version, one should again assume |x| > |y| and define the powers of x + y and x using a holomorphic branch of log defined on an open disk of radius |x| centered at x. The generalized binomial theorem is valid also for elements x and y of a Banach algebra as long as xy = yx, x is invertible, and ||y/x|| less than 1.A version of the binomial theorem is valid for the following Pochhammer symbol-like family of polynomials: for a given real constant c, define

and

and ![{\displaystyle x^{(n)}=\prod _{k=1}^{n}[x+(k-1)c]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fb041571bc1f80d3b23d148bd04e4245ebf4c9) for

for  . Then

. Then

The case c = 0 recovers the usual binomial theorem.

More generally, a sequence

of polynomials is said to be binomial if

of polynomials is said to be binomial if

for all

,

, and

for all

,

, and

.

on the space of polynomials is said to be the basis operator of the sequence

on the space of polynomials is said to be the basis operator of the sequence  if

if  and

and  for all

for all  . A sequence

. A sequence  is binomial if and only if its basis operator is a Delta operator. Writing

is binomial if and only if its basis operator is a Delta operator. Writing  for the shift by

for the shift by  operator, the Delta operators corresponding to the above "Pochhammer" families of polynomials are the backward difference

operator, the Delta operators corresponding to the above "Pochhammer" families of polynomials are the backward difference  for

for  , the ordinary derivative for

, the ordinary derivative for  , and the forward difference

, and the forward difference  for

for  .

.

Multinomial theorem

The binomial theorem can be generalized to include powers of sums with more than two terms. The general version iswhere the summation is taken over all sequences of nonnegative integer indices k1 through km such that the sum of all ki is n. (For each term in the expansion, the exponents must add up to n). The coefficients

are known as multinomial coefficients, and can be computed by the formula

are known as multinomial coefficients, and can be computed by the formula

Combinatorially, the multinomial coefficient

counts the number of different ways to partition an n-element set into disjoint subsets of sizes k1, ..., km.

counts the number of different ways to partition an n-element set into disjoint subsets of sizes k1, ..., km.

Multi-binomial theorem

It is often useful when working in more dimensions, to deal with products of binomial expressions. By the binomial theorem this is equal toThis may be written more concisely, by multi-index notation, as

Applications

Multiple-angle identities

For the complex numbers the binomial theorem can be combined with De Moivre's formula to yield multiple-angle formulas for the sine and cosine. According to De Moivre's formula,Series for e

The number e is often defined by the formulaDerivative of the power function

In finding the derivative of the power function f(x) = xn for integer n using the definition of derivative, one can expand the binomial (x + h)n.Nth derivative of a product

To indicate the formula for the derivative of order n of the product of two functions, the formula of the binomial theorem is used symbolically.Probability

The binomial theorem is closely related to the probability mass function of the negative binomial distribution. The probability of a (countable) collection of independent Bernoulli trials with probability of success

with probability of success ![{\displaystyle p\in [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/33c3a52aa7b2d00227e85c641cca67e85583c43c) all not happening is

all not happening is

A useful upper bound for this quantity is

.

.

The binomial theorem in abstract algebra

Formula (1) is valid more generally for any elements x and y of a semiring satisfying xy = yx. The theorem is true even more generally: alternativity suffices in place of associativity.The binomial theorem can be stated by saying that the polynomial sequence { 1, x, x2, x3, ... } is of binomial type.

In popular culture

- The binomial theorem is mentioned in the Major-General's Song in the comic opera The Pirates of Penzance.

- Professor Moriarty is described by Sherlock Holmes as having written a treatise on the binomial theorem.

- The Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, using the heteronym Álvaro de Campos, wrote that "Newton's Binomial is as beautiful as the Venus de Milo. The truth is that few people notice it."

- In the 2014 film The Imitation Game, Alan Turing makes reference to Isaac Newton's work on the Binomial Theorem during his first meeting with Commander Denniston at Bletchley Park.

![[(x+y)^{n+1}]_{j,k}=[(x+y)^{n}]_{j-1,k}+[(x+y)^{n}]_{j,k-1},](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/518ebfbee0b81ffcd211d9d6bc1bd574da3e1f40)