Slow motion computer simulation of the black hole binary system

GW150914 as seen by a nearby observer, during 0.33 s of its final

inspiral, merge, and ringdown. The star field behind the black holes is

being heavily distorted and appears to rotate and move, due to extreme gravitational lensing, as spacetime itself is distorted and dragged around by the rotating black holes.

General relativity (GR, also known as the general theory of relativity or GTR) is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and the current description of gravitation in modern physics. General relativity generalizes special relativity and Newton's law of universal gravitation, providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time, or spacetime. In particular, the curvature of spacetime is directly related to the energy and momentum of whatever matter and radiation are present. The relation is specified by the Einstein field equations, a system of partial differential equations.

Some predictions of general relativity differ significantly from those of classical physics, especially concerning the passage of time, the geometry of space, the motion of bodies in free fall, and the propagation of light. Examples of such differences include gravitational time dilation, gravitational lensing, the gravitational redshift of light, and the gravitational time delay. The predictions of general relativity in relation to classical physics have been confirmed in all observations and experiments to date. Although general relativity is not the only relativistic theory of gravity, it is the simplest theory that is consistent with experimental data. However, unanswered questions remain, the most fundamental being how general relativity can be reconciled with the laws of quantum physics to produce a complete and self-consistent theory of quantum gravity.

Einstein's theory has important astrophysical

implications. For example, it implies the existence of black

holes—regions of space in which space and time are distorted in such a

way that nothing, not even light, can escape—as an end-state for massive stars.

There is ample evidence that the intense radiation emitted by certain

kinds of astronomical objects is due to black holes; for example, microquasars and active galactic nuclei result from the presence of stellar black holes and supermassive black holes,

respectively. The bending of light by gravity can lead to the

phenomenon of gravitational lensing, in which multiple images of the

same distant astronomical object are visible in the sky. General

relativity also predicts the existence of gravitational waves, which have since been observed directly by the physics collaboration LIGO. In addition, general relativity is the basis of current cosmological models of a consistently expanding universe.

Widely acknowledged as a theory of extraordinary beauty, general relativity has often been described as the most beautiful of all existing physical theories.

History

Soon after publishing the special theory of relativity in 1905, Einstein started thinking about how to incorporate gravity into his new relativistic framework. In 1907, beginning with a simple thought experiment

involving an observer in free fall, he embarked on what would be an

eight-year search for a relativistic theory of gravity. After numerous

detours and false starts, his work culminated in the presentation to the

Prussian Academy of Science in November 1915 of what are now known as the Einstein field equations.

These equations specify how the geometry of space and time is

influenced by whatever matter and radiation are present, and form the

core of Einstein's general theory of relativity.

The Einstein field equations are nonlinear

and very difficult to solve. Einstein used approximation methods in

working out initial predictions of the theory. But as early as 1916, the

astrophysicist Karl Schwarzschild found the first non-trivial exact solution to the Einstein field equations, the Schwarzschild metric.

This solution laid the groundwork for the description of the final

stages of gravitational collapse, and the objects known today as black

holes. In the same year, the first steps towards generalizing

Schwarzschild's solution to electrically charged objects were taken, which eventually resulted in the Reissner–Nordström solution, now associated with electrically charged black holes. In 1917, Einstein applied his theory to the universe

as a whole, initiating the field of relativistic cosmology. In line

with contemporary thinking, he assumed a static universe, adding a new

parameter to his original field equations—the cosmological constant—to match that observational presumption. By 1929, however, the work of Hubble

and others had shown that our universe is expanding. This is readily

described by the expanding cosmological solutions found by Friedmann in 1922, which do not require a cosmological constant. Lemaître used these solutions to formulate the earliest version of the Big Bang models, in which our universe has evolved from an extremely hot and dense earlier state. Einstein later declared the cosmological constant the biggest blunder of his life.

During that period, general relativity remained something of a curiosity among physical theories. It was clearly superior to Newtonian gravity,

being consistent with special relativity and accounting for several

effects unexplained by the Newtonian theory. Einstein himself had shown

in 1915 how his theory explained the anomalous perihelion advance of the planet Mercury without any arbitrary parameters ("fudge factors"). Similarly, a 1919 expedition led by Eddington confirmed general relativity's prediction for the deflection of starlight by the Sun during the total solar eclipse of May 29, 1919, making Einstein instantly famous. Yet the theory entered the mainstream of theoretical physics and astrophysics only with the developments between approximately 1960 and 1975, now known as the golden age of general relativity. Physicists began to understand the concept of a black hole, and to identify quasars as one of these objects' astrophysical manifestations. Ever more precise solar system tests confirmed the theory's predictive power, and relativistic cosmology, too, became amenable to direct observational tests.

Over the years, general relativity has acquired a reputation as a theory of extraordinary beauty. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar has noted that at multiple levels, general relativity exhibits what Francis Bacon has termed, a "strangeness in the proportion" (i.e. elements that excite wonderment and surprise). It juxtaposes fundamental concepts (space and time versus

matter and motion) which had previously been considered as entirely

independent. Chandrasekhar also noted that Einstein's only guides in his

search for an exact theory were the principle of equivalence and his

sense that a proper description of gravity should be geometrical at its

basis, so that there was an "element of revelation" in the manner in

which Einstein arrived at his theory.

Other elements of beauty associated with the general theory of

relativity are its simplicity, symmetry, the manner in which it

incorporates invariance and unification, and its perfect logical

consistency.

From classical mechanics to general relativity

General

relativity can be understood by examining its similarities with and

departures from classical physics. The first step is the realization

that classical mechanics and Newton's law of gravity admit a geometric

description. The combination of this description with the laws of

special relativity results in a heuristic derivation of general

relativity.

Geometry of Newtonian gravity

According

to general relativity, objects in a gravitational field behave

similarly to objects within an accelerating enclosure. For example, an

observer will see a ball fall the same way in a rocket (left) as it does

on Earth (right), provided that the acceleration of the rocket is equal

to 9.8 m/s2 (the acceleration due to gravity at the surface of the Earth).

At the base of classical mechanics is the notion that a body's motion can be described as a combination of free (or inertial)

motion, and deviations from this free motion. Such deviations are

caused by external forces acting on a body in accordance with Newton's

second law of motion, which states that the net force acting on a body is equal to that body's (inertial) mass multiplied by its acceleration. The preferred inertial motions are related to the geometry of space and time: in the standard reference frames

of classical mechanics, objects in free motion move along straight

lines at constant speed. In modern parlance, their paths are geodesics, straight world lines in curved spacetime.

Conversely, one might expect that inertial motions, once

identified by observing the actual motions of bodies and making

allowances for the external forces (such as electromagnetism or friction), can be used to define the geometry of space, as well as a time coordinate.

However, there is an ambiguity once gravity comes into play. According

to Newton's law of gravity, and independently verified by experiments

such as that of Eötvös and its successors (see Eötvös experiment), there is a universality of free fall (also known as the weak equivalence principle, or the universal equality of inertial and passive-gravitational mass): the trajectory of a test body in free fall depends only on its position and initial speed, but not on any of its material properties. A simplified version of this is embodied in Einstein's elevator experiment,

illustrated in the figure on the right: for an observer in a small

enclosed room, it is impossible to decide, by mapping the trajectory of

bodies such as a dropped ball, whether the room is at rest in a

gravitational field, or in free space aboard a rocket that is

accelerating at a rate equal to that of the gravitational field.

Given the universality of free fall, there is no observable

distinction between inertial motion and motion under the influence of

the gravitational force. This suggests the definition of a new class of

inertial motion, namely that of objects in free fall under the influence

of gravity. This new class of preferred motions, too, defines a

geometry of space and time—in mathematical terms, it is the geodesic

motion associated with a specific connection which depends on the gradient of the gravitational potential. Space, in this construction, still has the ordinary Euclidean geometry. However, spacetime

as a whole is more complicated. As can be shown using simple thought

experiments following the free-fall trajectories of different test

particles, the result of transporting spacetime vectors that can denote a

particle's velocity (time-like vectors) will vary with the particle's

trajectory; mathematically speaking, the Newtonian connection is not integrable. From this, one can deduce that spacetime is curved. The resulting Newton–Cartan theory is a geometric formulation of Newtonian gravity using only covariant concepts, i.e. a description which is valid in any desired coordinate system. In this geometric description, tidal effects—the

relative acceleration of bodies in free fall—are related to the

derivative of the connection, showing how the modified geometry is

caused by the presence of mass.

Relativistic generalization

As intriguing as geometric Newtonian gravity may be, its basis, classical mechanics, is merely a limiting case of (special) relativistic mechanics. In the language of symmetry: where gravity can be neglected, physics is Lorentz invariant as in special relativity rather than Galilei invariant as in classical mechanics. (The defining symmetry of special relativity is the Poincaré group,

which includes translations, rotations and boosts.) The differences

between the two become significant when dealing with speeds approaching

the speed of light, and with high-energy phenomena.

With Lorentz symmetry, additional structures come into play. They

are defined by the set of light cones (see image). The light-cones

define a causal structure: for each event A, there is a set of events that can, in principle, either influence or be influenced by A via signals or interactions that do not need to travel faster than light (such as event B in the image), and a set of events for which such an influence is impossible (such as event C in the image). These sets are observer-independent.

In conjunction with the world-lines of freely falling particles, the

light-cones can be used to reconstruct the space–time's semi-Riemannian

metric, at least up to a positive scalar factor. In mathematical terms,

this defines a conformal structure or conformal geometry.

Special relativity is defined in the absence of gravity, so for

practical applications, it is a suitable model whenever gravity can be

neglected. Bringing gravity into play, and assuming the universality of

free fall, an analogous reasoning as in the previous section applies:

there are no global inertial frames.

Instead there are approximate inertial frames moving alongside freely

falling particles. Translated into the language of spacetime: the

straight time-like

lines that define a gravity-free inertial frame are deformed to lines

that are curved relative to each other, suggesting that the inclusion of

gravity necessitates a change in spacetime geometry.

A priori, it is not clear whether the new local frames in free

fall coincide with the reference frames in which the laws of special

relativity hold—that theory is based on the propagation of light, and

thus on electromagnetism, which could have a different set of preferred

frames. But using different assumptions about the special-relativistic

frames (such as their being earth-fixed, or in free fall), one can

derive different predictions for the gravitational redshift, that is,

the way in which the frequency of light shifts as the light propagates

through a gravitational field.

The actual measurements show that free-falling frames are the ones in

which light propagates as it does in special relativity.

The generalization of this statement, namely that the laws of special

relativity hold to good approximation in freely falling (and

non-rotating) reference frames, is known as the Einstein equivalence principle, a crucial guiding principle for generalizing special-relativistic physics to include gravity.

The same experimental data shows that time as measured by clocks in a gravitational field—proper time,

to give the technical term—does not follow the rules of special

relativity. In the language of spacetime geometry, it is not measured by

the Minkowski metric.

As in the Newtonian case, this is suggestive of a more general

geometry. At small scales, all reference frames that are in free fall

are equivalent, and approximately Minkowskian. Consequently, we are now

dealing with a curved generalization of Minkowski space. The metric tensor

that defines the geometry—in particular, how lengths and angles are

measured—is not the Minkowski metric of special relativity, it is a

generalization known as a semi- or pseudo-Riemannian metric. Furthermore, each Riemannian metric is naturally associated with one particular kind of connection, the Levi-Civita connection,

and this is, in fact, the connection that satisfies the equivalence

principle and makes space locally Minkowskian (that is, in suitable locally inertial coordinates, the metric is Minkowskian, and its first partial derivatives and the connection coefficients vanish).

Einstein's equations

Having formulated the relativistic, geometric version of the effects

of gravity, the question of gravity's source remains. In Newtonian

gravity, the source is mass. In special relativity, mass turns out to be

part of a more general quantity called the energy–momentum tensor, which includes both energy and momentum densities as well as stress: pressure and shear.

Using the equivalence principle, this tensor is readily generalized to

curved spacetime. Drawing further upon the analogy with geometric

Newtonian gravity, it is natural to assume that the field equation for gravity relates this tensor and the Ricci tensor,

which describes a particular class of tidal effects: the change in

volume for a small cloud of test particles that are initially at rest,

and then fall freely. In special relativity, conservation of energy–momentum corresponds to the statement that the energy–momentum tensor is divergence-free. This formula, too, is readily generalized to curved spacetime by replacing partial derivatives with their curved-manifold counterparts, covariant derivatives

studied in differential geometry. With this additional condition—the

covariant divergence of the energy–momentum tensor, and hence of

whatever is on the other side of the equation, is zero— the simplest set

of equations are what are called Einstein's (field) equations:

| Einstein's field equations

|

On the left-hand side is the Einstein tensor, a specific divergence-free combination of the Ricci tensor and the metric. Where is symmetric. In particular,

is the curvature scalar. The Ricci tensor itself is related to the more general Riemann curvature tensor as

On the right-hand side, is the energy–momentum tensor. All tensors are written in abstract index notation. Matching the theory's prediction to observational results for planetary orbits

or, equivalently, assuring that the weak-gravity, low-speed limit is

Newtonian mechanics, the proportionality constant can be fixed as κ = 8πG/c4, with G the gravitational constant and c the speed of light. When there is no matter present, so that the energy–momentum tensor vanishes, the results are the vacuum Einstein equations,

Alternatives to general relativity

There are alternatives to general relativity

built upon the same premises, which include additional rules and/or

constraints, leading to different field equations. Examples are Whitehead's theory, Brans–Dicke theory, teleparallelism, f(R) gravity and Einstein–Cartan theory.

Definition and basic applications

The derivation outlined in the previous section contains all the

information needed to define general relativity, describe its key

properties, and address a question of crucial importance in physics,

namely how the theory can be used for model-building.

Definition and basic properties

General relativity is a metric theory of gravitation. At its core are Einstein's equations, which describe the relation between the geometry of a four-dimensional pseudo-Riemannian manifold representing spacetime, and the energy–momentum contained in that spacetime. Phenomena that in classical mechanics are ascribed to the action of the force of gravity (such as free-fall, orbital motion, and spacecraft trajectories),

correspond to inertial motion within a curved geometry of spacetime in

general relativity; there is no gravitational force deflecting objects

from their natural, straight paths. Instead, gravity corresponds to

changes in the properties of space and time, which in turn changes the

straightest-possible paths that objects will naturally follow. The curvature is, in turn, caused by the energy–momentum of matter. Paraphrasing the relativist John Archibald Wheeler, spacetime tells matter how to move; matter tells spacetime how to curve.

While general relativity replaces the scalar gravitational potential of classical physics by a symmetric rank-two tensor, the latter reduces to the former in certain limiting cases. For weak gravitational fields and slow speed relative to the speed of light, the theory's predictions converge on those of Newton's law of universal gravitation.

As it is constructed using tensors, general relativity exhibits general covariance: its laws—and further laws formulated within the general relativistic framework—take on the same form in all coordinate systems. Furthermore, the theory does not contain any invariant geometric background structures, i.e. it is background independent. It thus satisfies a more stringent general principle of relativity, namely that the laws of physics are the same for all observers. Locally, as expressed in the equivalence principle, spacetime is Minkowskian, and the laws of physics exhibit local Lorentz invariance.

Model-building

The core concept of general-relativistic model-building is that of a solution of Einstein's equations.

Given both Einstein's equations and suitable equations for the

properties of matter, such a solution consists of a specific

semi-Riemannian manifold (usually defined by giving the metric in

specific coordinates), and specific matter fields defined on that

manifold. Matter and geometry must satisfy Einstein's equations, so in

particular, the matter's energy–momentum tensor must be divergence-free.

The matter must, of course, also satisfy whatever additional equations

were imposed on its properties. In short, such a solution is a model

universe that satisfies the laws of general relativity, and possibly

additional laws governing whatever matter might be present.

Einstein's equations are nonlinear partial differential equations and, as such, difficult to solve exactly. Nevertheless, a number of exact solutions are known, although only a few have direct physical applications. The best-known exact solutions, and also those most interesting from a physics point of view, are the Schwarzschild solution, the Reissner–Nordström solution and the Kerr metric, each corresponding to a certain type of black hole in an otherwise empty universe, and the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker and de Sitter universes, each describing an expanding cosmos. Exact solutions of great theoretical interest include the Gödel universe (which opens up the intriguing possibility of time travel in curved spacetimes), the Taub-NUT solution (a model universe that is homogeneous, but anisotropic), and anti-de Sitter space (which has recently come to prominence in the context of what is called the Maldacena conjecture).

Given the difficulty of finding exact solutions, Einstein's field equations are also solved frequently by numerical integration on a computer, or by considering small perturbations of exact solutions. In the field of numerical relativity,

powerful computers are employed to simulate the geometry of spacetime

and to solve Einstein's equations for interesting situations such as two

colliding black holes.

In principle, such methods may be applied to any system, given

sufficient computer resources, and may address fundamental questions

such as naked singularities. Approximate solutions may also be found by perturbation theories such as linearized gravity and its generalization, the post-Newtonian expansion,

both of which were developed by Einstein. The latter provides a

systematic approach to solving for the geometry of a spacetime that

contains a distribution of matter that moves slowly compared with the

speed of light. The expansion involves a series of terms; the first

terms represent Newtonian gravity, whereas the later terms represent

ever smaller corrections to Newton's theory due to general relativity.

An extension of this expansion is the parametrized post-Newtonian (PPN)

formalism, which allows quantitative comparisons between the

predictions of general relativity and alternative theories.

Consequences of Einstein's theory

General

relativity has a number of physical consequences. Some follow directly

from the theory's axioms, whereas others have become clear only in the

course of many years of research that followed Einstein's initial

publication.

Gravitational time dilation and frequency shift

Schematic representation of the gravitational redshift of a light wave escaping from the surface of a massive body

Assuming that the equivalence principle holds, gravity influences the passage of time. Light sent down into a gravity well is blueshifted, whereas light sent in the opposite direction (i.e., climbing out of the gravity well) is redshifted;

collectively, these two effects are known as the gravitational

frequency shift. More generally, processes close to a massive body run

more slowly when compared with processes taking place farther away; this

effect is known as gravitational time dilation.

Gravitational redshift has been measured in the laboratory and using astronomical observations. Gravitational time dilation in the Earth's gravitational field has been measured numerous times using atomic clocks, while ongoing validation is provided as a side effect of the operation of the Global Positioning System (GPS). Tests in stronger gravitational fields are provided by the observation of binary pulsars. All results are in agreement with general relativity.

However, at the current level of accuracy, these observations cannot

distinguish between general relativity and other theories in which the

equivalence principle is valid.

Light deflection and gravitational time delay

Deflection of light (sent out from the location shown in blue) near a compact body (shown in gray)

General relativity predicts that the path of light will follow the

curvature of spacetime as it passes near a star. This effect was

initially confirmed by observing the light of stars or distant quasars

being deflected as it passes the Sun.

This and related predictions follow from the fact that light

follows what is called a light-like or null geodesic—a generalization of

the straight lines along which light travels in classical physics. Such

geodesics are the generalization of the invariance of lightspeed in special relativity.

As one examines suitable model spacetimes (either the exterior

Schwarzschild solution or, for more than a single mass, the

post-Newtonian expansion),

several effects of gravity on light propagation emerge. Although the

bending of light can also be derived by extending the universality of

free fall to light, the angle of deflection resulting from such calculations is only half the value given by general relativity.

Closely related to light deflection is the gravitational time

delay (or Shapiro delay), the phenomenon that light signals take longer

to move through a gravitational field than they would in the absence of

that field. There have been numerous successful tests of this

prediction. In the parameterized post-Newtonian formalism

(PPN), measurements of both the deflection of light and the

gravitational time delay determine a parameter called γ, which encodes

the influence of gravity on the geometry of space.

Gravitational waves

Ring of test particles deformed by a passing (linearized, amplified for better visibility) gravitational wave

Predicted in 1916

by Albert Einstein, there are gravitational waves: ripples in the

metric of spacetime that propagate at the speed of light. These are one

of several analogies between weak-field gravity and electromagnetism in

that, they are analogous to electromagnetic waves. On February 11, 2016, the Advanced LIGO team announced that they had directly detected gravitational waves from a pair of black holes merging.

The simplest type of such a wave can be visualized by its action

on a ring of freely floating particles. A sine wave propagating through

such a ring towards the reader distorts the ring in a characteristic,

rhythmic fashion (animated image to the right). Since Einstein's equations are non-linear, arbitrarily strong gravitational waves do not obey linear superposition,

making their description difficult. However, for weak fields, a linear

approximation can be made. Such linearized gravitational waves are

sufficiently accurate to describe the exceedingly weak waves that are

expected to arrive here on Earth from far-off cosmic events, which

typically result in relative distances increasing and decreasing by or less. Data analysis methods routinely make use of the fact that these linearized waves can be Fourier decomposed.

Some exact solutions describe gravitational waves without any approximation, e.g., a wave train traveling through empty space or Gowdy universes, varieties of an expanding cosmos filled with gravitational waves.

But for gravitational waves produced in astrophysically relevant

situations, such as the merger of two black holes, numerical methods are

presently the only way to construct appropriate models.

Orbital effects and the relativity of direction

General relativity differs from classical mechanics in a number of

predictions concerning orbiting bodies. It predicts an overall rotation (precession)

of planetary orbits, as well as orbital decay caused by the emission of

gravitational waves and effects related to the relativity of direction.

Precession of apsides

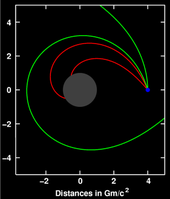

Newtonian (red) vs. Einsteinian orbit (blue) of a lone planet orbiting a star

In general relativity, the apsides of any orbit (the point of the orbiting body's closest approach to the system's center of mass) will precess; the orbit is not an ellipse, but akin to an ellipse that rotates on its focus, resulting in a rose curve-like

shape. Einstein first derived this result by using an

approximate metric representing the Newtonian limit and treating the

orbiting body as a test particle.

For him, the fact that his theory gave a straightforward explanation of

Mercury's anomalous perihelion shift, discovered earlier by Urbain Le Verrier in 1859, was important evidence that he had at last identified the correct form of the gravitational field equations.

The effect can also be derived by using either the exact Schwarzschild metric (describing spacetime around a spherical mass) or the much more general post-Newtonian formalism. It is due to the influence of gravity on the geometry of space and to the contribution of self-energy to a body's gravity (encoded in the nonlinearity of Einstein's equations).

Relativistic precession has been observed for all planets that allow

for accurate precession measurements (Mercury, Venus, and Earth), as well as in binary pulsar systems, where it is larger by five orders of magnitude.

In general relativity the perihelion shift σ, expressed in radians per revolution, is approximately given by:

where:

- is the semi-major axis

- is the orbital period

- is the speed of light

- is the orbital eccentricity

Orbital decay

Orbital decay for PSR1913+16: time shift in seconds, tracked over three decades.

According to general relativity, a binary system

will emit gravitational waves, thereby losing energy. Due to this loss,

the distance between the two orbiting bodies decreases, and so does

their orbital period. Within the Solar System or for ordinary double stars, the effect is too small to be observable. This is not the case for a close binary pulsar, a system of two orbiting neutron stars,

one of which is a pulsar: from the pulsar, observers on Earth receive a

regular series of radio pulses that can serve as a highly accurate

clock, which allows precise measurements of the orbital period. Because

neutron stars are immensely compact, significant amounts of energy are

emitted in the form of gravitational radiation.

The first observation of a decrease in orbital period due to the emission of gravitational waves was made by Hulse and Taylor, using the binary pulsar PSR1913+16

they had discovered in 1974. This was the first detection of

gravitational waves, albeit indirect, for which they were awarded the

1993 Nobel Prize in physics. Since then, several other binary pulsars have been found, in particular the double pulsar PSR J0737-3039, in which both stars are pulsars.

Geodetic precession and frame-dragging

Several relativistic effects are directly related to the relativity of direction. One is geodetic precession: the axis direction of a gyroscope

in free fall in curved spacetime will change when compared, for

instance, with the direction of light received from distant stars—even

though such a gyroscope represents the way of keeping a direction as

stable as possible ("parallel transport"). For the Moon–Earth system, this effect has been measured with the help of lunar laser ranging. More recently, it has been measured for test masses aboard the satellite Gravity Probe B to a precision of better than 0.3%.

Near a rotating mass, there are gravitomagnetic or frame-dragging effects. A distant observer will determine that objects close to the mass get "dragged around". This is most extreme for rotating black holes where, for any object entering a zone known as the ergosphere, rotation is inevitable. Such effects can again be tested through their influence on the orientation of gyroscopes in free fall. Somewhat controversial tests have been performed using the LAGEOS satellites, confirming the relativistic prediction. Also the Mars Global Surveyor probe around Mars has been used.

Astrophysical applications

Gravitational lensing

Einstein cross: four images of the same astronomical object, produced by a gravitational lens

The deflection of light by gravity is responsible for a new class of

astronomical phenomena. If a massive object is situated between the

astronomer and a distant target object with appropriate mass and

relative distances, the astronomer will see multiple distorted images of

the target. Such effects are known as gravitational lensing. Depending on the configuration, scale, and mass distribution, there can be two or more images, a bright ring known as an Einstein ring, or partial rings called arcs.

The earliest example was discovered in 1979; since then, more than a hundred gravitational lenses have been observed.

Even if the multiple images are too close to each other to be resolved,

the effect can still be measured, e.g., as an overall brightening of

the target object; a number of such "microlensing events" have been observed.

Gravitational lensing has developed into a tool of observational astronomy. It is used to detect the presence and distribution of dark matter, provide a "natural telescope" for observing distant galaxies, and to obtain an independent estimate of the Hubble constant. Statistical evaluations of lensing data provide valuable insight into the structural evolution of galaxies.

Gravitational wave astronomy

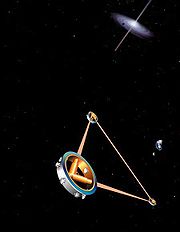

Artist's impression of the space-borne gravitational wave detector LISA

Observations of binary pulsars provide strong indirect evidence for the existence of gravitational waves (see Orbital decay, above). Detection of these waves is a major goal of current relativity-related research. Several land-based gravitational wave detectors are currently in operation, most notably the interferometric detectors GEO 600, LIGO (two detectors), TAMA 300 and VIRGO. Various pulsar timing arrays are using millisecond pulsars to detect gravitational waves in the 10−9 to 10−6 Hertz frequency range, which originate from binary supermassive blackholes. A European space-based detector, eLISA / NGO, is currently under development, with a precursor mission (LISA Pathfinder) having launched in December 2015.

Observations of gravitational waves promise to complement observations in the electromagnetic spectrum.

They are expected to yield information about black holes and other

dense objects such as neutron stars and white dwarfs, about certain

kinds of supernova implosions, and about processes in the very early universe, including the signature of certain types of hypothetical cosmic string. In February 2016, the Advanced LIGO team announced that they had detected gravitational waves from a black hole merger.

Black holes and other compact objects

Whenever the ratio of an object's mass to its radius becomes

sufficiently large, general relativity predicts the formation of a black

hole, a region of space from which nothing, not even light, can escape.

In the currently accepted models of stellar evolution, neutron stars of around 1.4 solar masses,

and stellar black holes with a few to a few dozen solar masses, are

thought to be the final state for the evolution of massive stars. Usually a galaxy has one supermassive black hole with a few million to a few billion solar masses in its center, and its presence is thought to have played an important role in the formation of the galaxy and larger cosmic structures.

Simulation

based on the equations of general relativity: a star collapsing to form

a black hole while emitting gravitational waves

Astronomically, the most important property of compact objects is

that they provide a supremely efficient mechanism for converting

gravitational energy into electromagnetic radiation. Accretion,

the falling of dust or gaseous matter onto stellar or supermassive

black holes, is thought to be responsible for some spectacularly

luminous astronomical objects, notably diverse kinds of active galactic

nuclei on galactic scales and stellar-size objects such as microquasars. In particular, accretion can lead to relativistic jets, focused beams of highly energetic particles that are being flung into space at almost light speed.

General relativity plays a central role in modelling all these phenomena, and observations provide strong evidence for the existence of black holes with the properties predicted by the theory.

Black holes are also sought-after targets in the search for gravitational waves (cf. Gravitational waves, above). Merging black hole binaries

should lead to some of the strongest gravitational wave signals

reaching detectors here on Earth, and the phase directly before the

merger ("chirp") could be used as a "standard candle" to deduce the distance to the merger events–and hence serve as a probe of cosmic expansion at large distances.

The gravitational waves produced as a stellar black hole plunges into a

supermassive one should provide direct information about the

supermassive black hole's geometry.

Cosmology

This

blue horseshoe is a distant galaxy that has been magnified and warped

into a nearly complete ring by the strong gravitational pull of the

massive foreground luminous red galaxy.

The current models of cosmology are based on Einstein's field equations, which include the cosmological constant Λ since it has important influence on the large-scale dynamics of the cosmos,

where is the spacetime metric. Isotropic and homogeneous solutions of these enhanced equations, the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker solutions, allow physicists to model a universe that has evolved over the past 14 billion years from a hot, early Big Bang phase. Once a small number of parameters (for example the universe's mean matter density) have been fixed by astronomical observation, further observational data can be used to put the models to the test. Predictions, all successful, include the initial abundance of chemical elements formed in a period of primordial nucleosynthesis, the large-scale structure of the universe, and the existence and properties of a "thermal echo" from the early cosmos, the cosmic background radiation.

Astronomical observations of the cosmological expansion rate

allow the total amount of matter in the universe to be estimated,

although the nature of that matter remains mysterious in part. About 90%

of all matter appears to be dark matter, which has mass (or,

equivalently, gravitational influence), but does not interact

electromagnetically and, hence, cannot be observed directly. There is no generally accepted description of this new kind of matter, within the framework of known particle physics or otherwise.

Observational evidence from redshift surveys of distant supernovae and

measurements of the cosmic background radiation also show that the

evolution of our universe is significantly influenced by a cosmological

constant resulting in an acceleration of cosmic expansion or,

equivalently, by a form of energy with an unusual equation of state, known as dark energy, the nature of which remains unclear.

An inflationary phase, an additional phase of strongly accelerated expansion at cosmic times of around 10−33

seconds, was hypothesized in 1980 to account for several puzzling

observations that were unexplained by classical cosmological models,

such as the nearly perfect homogeneity of the cosmic background

radiation. Recent measurements of the cosmic background radiation have resulted in the first evidence for this scenario. However, there is a bewildering variety of possible inflationary scenarios, which cannot be restricted by current observations.

An even larger question is the physics of the earliest universe, prior

to the inflationary phase and close to where the classical models

predict the big bang singularity. An authoritative answer would require a complete theory of quantum gravity, which has not yet been developed.

Time travel

Kurt Gödel showed that solutions to Einstein's equations exist that contain closed timelike curves

(CTCs), which allow for loops in time. The solutions require extreme

physical conditions unlikely ever to occur in practice, and it remains

an open question whether further laws of physics will eliminate them

completely. Since then, other—similarly impractical—GR solutions

containing CTCs have been found, such as the Tipler cylinder and traversable wormholes.

Advanced concepts

Causal structure and global geometry

Penrose–Carter diagram of an infinite Minkowski universe

In general relativity, no material body can catch up with or overtake a light pulse. No influence from an event A can reach any other location X before light sent out at A to X. In consequence, an exploration of all light worldlines (null geodesics) yields key information about the spacetime's causal structure. This structure can be displayed using Penrose–Carter diagrams in which infinitely large regions of space and infinite time intervals are shrunk ("compactified") so as to fit onto a finite map, while light still travels along diagonals as in standard spacetime diagrams.

Aware of the importance of causal structure, Roger Penrose and others developed what is known as global geometry.

In global geometry, the object of study is not one particular solution

(or family of solutions) to Einstein's equations. Rather, relations that

hold true for all geodesics, such as the Raychaudhuri equation, and additional non-specific assumptions about the nature of matter (usually in the form of energy conditions) are used to derive general results.

Horizons

Using global geometry, some spacetimes can be shown to contain boundaries called horizons,

which demarcate one region from the rest of spacetime. The best-known

examples are black holes: if mass is compressed into a sufficiently

compact region of space (as specified in the hoop conjecture, the relevant length scale is the Schwarzschild radius),

no light from inside can escape to the outside. Since no object can

overtake a light pulse, all interior matter is imprisoned as well.

Passage from the exterior to the interior is still possible, showing

that the boundary, the black hole's horizon, is not a physical barrier.

The ergosphere of a rotating black hole, which plays a key role when it comes to extracting energy from such a black hole

Early studies of black holes relied on explicit solutions of

Einstein's equations, notably the spherically symmetric Schwarzschild

solution (used to describe a static black hole) and the axisymmetric Kerr solution (used to describe a rotating, stationary

black hole, and introducing interesting features such as the

ergosphere). Using global geometry, later studies have revealed more

general properties of black holes. In the long run, they are rather

simple objects characterized by eleven parameters specifying energy, linear momentum, angular momentum, location at a specified time and electric charge. This is stated by the black hole uniqueness theorems:

"black holes have no hair", that is, no distinguishing marks like the

hairstyles of humans. Irrespective of the complexity of a gravitating

object collapsing to form a black hole, the object that results (having

emitted gravitational waves) is very simple.

Even more remarkably, there is a general set of laws known as black hole mechanics, which is analogous to the laws of thermodynamics.

For instance, by the second law of black hole mechanics, the area of

the event horizon of a general black hole will never decrease with time,

analogous to the entropy

of a thermodynamic system. This limits the energy that can be extracted

by classical means from a rotating black hole.

There is strong evidence that the laws of black hole mechanics are, in

fact, a subset of the laws of thermodynamics, and that the black hole

area is proportional to its entropy.

This leads to a modification of the original laws of black hole

mechanics: for instance, as the second law of black hole mechanics

becomes part of the second law of thermodynamics, it is possible for

black hole area to decrease—as long as other processes ensure that,

overall, entropy increases. As thermodynamical objects with non-zero

temperature, black holes should emit thermal radiation. Semi-classical calculations indicate that indeed they do, with the surface gravity playing the role of temperature in Planck's law. This radiation is known as Hawking radiation (cf. the quantum theory section, below).

There are other types of horizons. In an expanding universe, an

observer may find that some regions of the past cannot be observed ("particle horizon"), and some regions of the future cannot be influenced (event horizon). Even in flat Minkowski space, when described by an accelerated observer (Rindler space), there will be horizons associated with a semi-classical radiation known as Unruh radiation.

Singularities

Another general feature of general relativity is the appearance of

spacetime boundaries known as singularities. Spacetime can be explored

by following up on timelike and lightlike geodesics—all possible ways

that light and particles in free fall can travel. But some solutions of

Einstein's equations have "ragged edges"—regions known as spacetime singularities,

where the paths of light and falling particles come to an abrupt end,

and geometry becomes ill-defined. In the more interesting cases, these

are "curvature singularities", where geometrical quantities

characterizing spacetime curvature, such as the Ricci scalar, take on infinite values.

Well-known examples of spacetimes with future singularities—where

worldlines end—are the Schwarzschild solution, which describes a

singularity inside an eternal static black hole, or the Kerr solution with its ring-shaped singularity inside an eternal rotating black hole.

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker solutions and other spacetimes

describing universes have past singularities on which worldlines begin,

namely Big Bang singularities, and some have future singularities (Big Crunch) as well.

Given that these examples are all highly symmetric—and thus

simplified—it is tempting to conclude that the occurrence of

singularities is an artifact of idealization. The famous singularity theorems,

proved using the methods of global geometry, say otherwise:

singularities are a generic feature of general relativity, and

unavoidable once the collapse of an object with realistic matter

properties has proceeded beyond a certain stage and also at the beginning of a wide class of expanding universes.

However, the theorems say little about the properties of singularities,

and much of current research is devoted to characterizing these

entities' generic structure (hypothesized e.g. by the BKL conjecture). The cosmic censorship hypothesis

states that all realistic future singularities (no perfect symmetries,

matter with realistic properties) are safely hidden away behind a

horizon, and thus invisible to all distant observers. While no formal

proof yet exists, numerical simulations offer supporting evidence of its

validity.

Evolution equations

Each solution of Einstein's equation encompasses the whole history of

a universe — it is not just some snapshot of how things are, but a

whole, possibly matter-filled, spacetime. It describes the state of

matter and geometry everywhere and at every moment in that particular

universe. Due to its general covariance, Einstein's theory is not

sufficient by itself to determine the time evolution of the metric tensor. It must be combined with a coordinate condition, which is analogous to gauge fixing in other field theories.

To understand Einstein's equations as partial differential

equations, it is helpful to formulate them in a way that describes the

evolution of the universe over time. This is done in "3+1" formulations,

where spacetime is split into three space dimensions and one time

dimension. The best-known example is the ADM formalism. These decompositions show that the spacetime evolution equations of general relativity are well-behaved: solutions always exist, and are uniquely defined, once suitable initial conditions have been specified. Such formulations of Einstein's field equations are the basis of numerical relativity.

Global and quasi-local quantities

The notion of evolution equations is intimately tied in with another

aspect of general relativistic physics. In Einstein's theory, it turns

out to be impossible to find a general definition for a seemingly simple

property such as a system's total mass (or energy). The main reason is

that the gravitational field—like any physical field—must be ascribed a

certain energy, but that it proves to be fundamentally impossible to

localize that energy.

Nevertheless, there are possibilities to define a system's total

mass, either using a hypothetical "infinitely distant observer" (ADM mass) or suitable symmetries (Komar mass).

If one excludes from the system's total mass the energy being carried

away to infinity by gravitational waves, the result is the Bondi mass at null infinity. Just as in classical physics, it can be shown that these masses are positive. Corresponding global definitions exist for momentum and angular momentum. There have also been a number of attempts to define quasi-local

quantities, such as the mass of an isolated system formulated using

only quantities defined within a finite region of space containing that

system. The hope is to obtain a quantity useful for general statements

about isolated systems, such as a more precise formulation of the hoop conjecture.

Relationship with quantum theory

If

general relativity were considered to be one of the two pillars of

modern physics, then quantum theory, the basis of understanding matter

from elementary particles to solid state physics, would be the other. However, how to reconcile quantum theory with general relativity is still an open question.

Quantum field theory in curved spacetime

Ordinary quantum field theories,

which form the basis of modern elementary particle physics, are defined

in flat Minkowski space, which is an excellent approximation when it

comes to describing the behavior of microscopic particles in weak

gravitational fields like those found on Earth.

In order to describe situations in which gravity is strong enough to

influence (quantum) matter, yet not strong enough to require

quantization itself, physicists have formulated quantum field theories

in curved spacetime. These theories rely on general relativity to

describe a curved background spacetime, and define a generalized quantum

field theory to describe the behavior of quantum matter within that

spacetime. Using this formalism, it can be shown that black holes emit a blackbody spectrum of particles known as Hawking radiation leading to the possibility that they evaporate over time. As briefly mentioned above, this radiation plays an important role for the thermodynamics of black holes.

Quantum gravity

The demand for consistency between a quantum description of matter and a geometric description of spacetime,

as well as the appearance of singularities (where curvature length

scales become microscopic), indicate the need for a full theory of

quantum gravity: for an adequate description of the interior of black

holes, and of the very early universe, a theory is required in which

gravity and the associated geometry of spacetime are described in the

language of quantum physics.

Despite major efforts, no complete and consistent theory of quantum

gravity is currently known, even though a number of promising candidates

exist.

Projection of a Calabi–Yau manifold, one of the ways of compactifying the extra dimensions posited by string theory

Attempts to generalize ordinary quantum field theories, used in

elementary particle physics to describe fundamental interactions, so as

to include gravity have led to serious problems. Some have argued that at low energies, this approach proves successful, in that it results in an acceptable effective (quantum) field theory of gravity.

At very high energies, however, the perturbative results are badly

divergent and lead to models devoid of predictive power ("perturbative non-renormalizability").

Simple spin network of the type used in loop quantum gravity.

One attempt to overcome these limitations is string theory, a quantum theory not of point particles, but of minute one-dimensional extended objects. The theory promises to be a unified description of all particles and interactions, including gravity; the price to pay is unusual features such as six extra dimensions of space in addition to the usual three. In what is called the second superstring revolution, it was conjectured that both string theory and a unification of general relativity and supersymmetry known as supergravity form part of a hypothesized eleven-dimensional model known as M-theory, which would constitute a uniquely defined and consistent theory of quantum gravity.

Another approach starts with the canonical quantization procedures of quantum theory. Using the initial-value-formulation of general relativity (cf. evolution equations above), the result is the Wheeler–deWitt equation (an analogue of the Schrödinger equation) which, regrettably, turns out to be ill-defined without a proper ultraviolet (lattice) cutoff. However, with the introduction of what are now known as Ashtekar variables, this leads to a promising model known as loop quantum gravity. Space is represented by a web-like structure called a spin network, evolving over time in discrete steps.

Depending on which features of general relativity and quantum

theory are accepted unchanged, and on what level changes are introduced,

there are numerous other attempts to arrive at a viable theory of

quantum gravity, some examples being the lattice theory of gravity based

on the Feynman Path Integral approach and Regge Calculus, dynamical triangulations, causal sets, twistor models, or the path integral based models of quantum cosmology.

All candidate theories still have major formal and conceptual

problems to overcome. They also face the common problem that, as yet,

there is no way to put quantum gravity predictions to experimental tests

(and thus to decide between the candidates where their predictions

vary), although there is hope for this to change as future data from

cosmological observations and particle physics experiments becomes

available.

Current status

Observation of gravitational waves from binary black hole merger GW150914.

General relativity has emerged as a highly successful model of

gravitation and cosmology, which has so far passed many unambiguous

observational and experimental tests. However, there are strong

indications the theory is incomplete. The problem of quantum gravity and the question of the reality of spacetime singularities remain open. Observational data that is taken as evidence for dark energy and dark matter could indicate the need for new physics.

Even taken as is, general relativity is rich with possibilities for

further exploration. Mathematical relativists seek to understand the

nature of singularities and the fundamental properties of Einstein's

equations, while numerical relativists run increasingly powerful computer simulations (such as those describing merging black holes).

In February 2016, it was announced that the existence of gravitational

waves was directly detected by the Advanced LIGO team on September 14,

2015. A century after its introduction, general relativity remains a highly active area of research.