| Uses | Small sample observation |

|---|---|

| Notable experiments | Discovery of cells |

| Related items | Microscope Electron microscope Scanning probe microscope |

A modern microscope with a mercury bulb for fluorescence microscopy. The microscope has a digital camera, and is attached to a computer.

The optical microscope, often referred to as the light microscope, is a type of microscope that commonly uses visible light and a system of lenses

to magnify images of small objects. Optical microscopes are the oldest

design of microscope and were possibly invented in their present compound form in the 17th century. Basic optical microscopes can be very simple, although many complex designs aim to improve resolution and sample contrast. Often used in the classroom and at home unlike the electron microscope which is used for closer viewing.

The image from an optical microscope can be captured by normal, photosensitive cameras to generate a micrograph. Originally images were captured by photographic film, but modern developments in CMOS and charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras allow the capture of digital images. Purely digital microscopes

are now available which use a CCD camera to examine a sample, showing

the resulting image directly on a computer screen without the need for eyepieces.

Alternatives to optical microscopy which do not use visible light include scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy and scanning probe microscopy.

On 8 October 2014, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Eric Betzig, William Moerner and Stefan Hell for "the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy," which brings "optical microscopy into the nanodimension".

Types

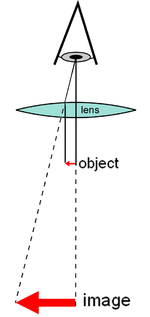

Diagram of a simple microscope

There are two basic types of optical microscopes: simple microscopes

and compound microscopes. A simple microscope is one which uses a single

lens for magnification, such as a magnifying glass. A compound

microscope uses several lenses to enhance the magnification of an

object. The vast majority of modern research microscopes are compound microscopes while some cheaper commercial digital microscopes

are simple single lens microscopes. Compound microscopes can be further

divided into a variety of other types of microscopes which differ in

their optical configurations, cost, and intended purposes.

Regular microscope

A

regular microscope uses a lens or set of lenses to enlarge an object

through angular magnification alone, giving the viewer an erect enlarged

virtual image. The use of a single convex lens or groups of lenses are found in simple magnification devices such as the magnifying glass, loupes, and eyepieces for telescopes and microscopes.

Compound microscope

Diagram of a compound microscope

A compound microscope uses a lens close to the object being viewed to collect light (called the objective lens) which focuses a real image of the object inside the microscope (image 1). That image is then magnified by a second lens or group of lenses (called the eyepiece) that gives the viewer an enlarged inverted virtual image of the object (image 2).

The use of a compound objective/eyepiece combination allows for much

higher magnification. Common compound microscopes often feature

exchangeable objective lenses, allowing the user to quickly adjust the

magnification. A compound microscope also enables more advanced illumination setups, such as phase contrast.

Other microscope variants

There

are many variants of the compound optical microscope design for

specialized purposes. Some of these are physical design differences

allowing specialization for certain purposes:

- Stereo microscope, a low-powered microscope which provides a stereoscopic view of the sample, commonly used for dissection.

- Comparison microscope, which has two separate light paths allowing direct comparison of two samples via one image in each eye.

- Inverted microscope, for studying samples from below; useful for cell cultures in liquid, or for metallography.

- Fiber optic connector inspection microscope, designed for connector end-face inspection

- Traveling microscope, for studying samples of high optical resolution.

Other microscope variants are designed for different illumination techniques:

- Petrographic microscope, whose design usually includes a polarizing filter, rotating stage and gypsum plate to facilitate the study of minerals or other crystalline materials whose optical properties can vary with orientation.

- Polarizing microscope, similar to the petrographic microscope.

- Phase contrast microscope, which applies the phase contrast illumination method.

- Epifluorescence microscope, designed for analysis of samples which include fluorophores.

- Confocal microscope, a widely used variant of epifluorescent illumination which uses a scanning laser to illuminate a sample for fluorescence.

- Two-photon microscope, used to image fluorescence deeper in scattering media and reduce photobleaching, especially in living samples.

- Student microscope – an often low-power microscope with simplified controls and sometimes low quality optics designed for school use or as a starter instrument for children.

- Ultramicroscope, an adapted light microscope that uses light scattering to allow viewing of tiny particles whose diameter is below or near the wavelength of visible light (around 500 nanometers); mostly obsolete since the advent of electron microscopes

Digital microscope

A miniature USB microscope.

A digital microscope is a microscope equipped with a digital camera allowing observation of a sample via a computer.

Microscopes can also be partly or wholly computer-controlled with

various levels of automation. Digital microscopy allows greater analysis

of a microscope image, for example measurements of distances and areas

and quantitaton of a fluorescent or histological stain.

Low-powered digital microscopes, USB microscopes, are also commercially available. These are essentially webcams with a high-powered macro lens and generally do not use transillumination. The camera attached directly to the USB

port of a computer, so that the images are shown directly on the

monitor. They offer modest magnifications (up to about 200×) without the

need to use eyepieces, and at very low cost. High power illumination is

usually provided by an LED source or sources adjacent to the camera lens.

Digital microscopy with very low light levels to avoid damage to vulnerable biological samples is available using sensitive photon-counting digital cameras. It has been demonstrated that a light source providing pairs of entangled photons may minimize the risk of damage to the most light-sensitive samples. In this application of ghost imaging

to photon-sparse microscopy, the sample is illuminated with infrared

photons, each of which is spatially correlated with an entangled partner

in the visible band for efficient imaging by a photon-counting camera.

History

Invention

The earliest microscopes were single lens magnifying glasses with limited magnification which date at least as far back as the widespread use of lenses in eyeglasses in the 13th century.

Compound microscopes first appeared in Europe around 1620 including one demonstrated by Cornelis Drebbel in London (around 1621) and one exhibited in Rome in 1624.

The actual inventor of the compound microscope is unknown

although many claims have been made over the years. These include a

claim 35 years after they appeared by Dutch spectacle-maker Johannes Zachariassen that his father, Zacharias Janssen, invented the compound microscope and/or the telescope as early as 1590. Johannes' (some claim dubious)

testimony pushes the invention date so far back that Zacharias would

have been a child at the time, leading to speculation that, for

Johannes' claim to be true, the compound microscope would have to have

been invented by Johannes' grandfather, Hans Martens. Another claim is that Janssen's competitor, Hans Lippershey (who applied for the first telescope patent in 1608) also invented the compound microscope. Other historians point to the Dutch innovator Cornelis Drebbel with his 1621 compound microscope.

Galileo Galilei

is also sometimes cited as a compound microscope inventor. After 1610

he found that he could close focus his telescope to view small objects,

such as flies, close up and/or could look through the wrong end in reverse to magnify small objects. The only drawback was that his 2 foot long telescope had to be extended out to 6 feet to view objects that close. After seeing the compound microscope built by Drebbel exhibited in Rome in 1624, Galileo built his own improved version. In 1625 Giovanni Faber coined the name microscope for the compound microscope Galileo submitted to the Accademia dei Lincei in 1624 (Galileo had called it the "occhiolino" or "little eye"). Faber coined the name from the Greek words μικρόν (micron) meaning "small", and σκοπεῖν (skopein) meaning "to look at", a name meant to be analogous with "telescope", another word coined by the Linceans.

Christiaan Huygens, another Dutchman, developed a simple 2-lens ocular system in the late 17th century that was achromatically

corrected, and therefore a huge step forward in microscope development.

The Huygens ocular is still being produced to this day, but suffers

from a small field size, and other minor disadvantages.

Popularization

The oldest published image known to have been made with a microscope: bees by Francesco Stelluti, 1630

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

(1632–1724) is credited with bringing the microscope to the attention

of biologists, even though simple magnifying lenses were already being

produced in the 16th century. Van Leeuwenhoek's home-made microscopes

were simple microscopes, with a single very small, yet strong lens. They

were awkward in use, but enabled van Leeuwenhoek to see detailed

images. It took about 150 years of optical development before the

compound microscope was able to provide the same quality image as van

Leeuwenhoek's simple microscopes, due to difficulties in configuring

multiple lenses. In the 1850s John Leonard Riddell, Professor of Chemistry at Tulane University,

invented the first practical binocular microscope while carrying out

one of the earliest and most extensive American microscopic

investigations of cholera.

Lighting techniques

While

basic microscope technology and optics have been available for over 400

years it is much more recently that techniques in sample illumination

were developed to generate the high quality images seen today.

In August 1893 August Köhler developed Köhler illumination.

This method of sample illumination gives rise to extremely even

lighting and overcomes many limitations of older techniques of sample

illumination. Before development of Köhler illumination the image of the

light source, for example a lightbulb filament, was always visible in the image of the sample.

The Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Dutch physicist Frits Zernike in 1953 for his development of phase contrast illumination which allows imaging of transparent samples. By using interference rather than absorption of light, extremely transparent samples, such as live mammalian cells, can be imaged without having to use staining techniques. Just two years later, in 1955, Georges Nomarski published the theory for differential interference contrast microscopy, another interference-based imaging technique.

Fluorescence microscopy

Modern biological microscopy depends heavily on the development of fluorescent probes for specific structures within a cell. In contrast to normal trans-illuminated light microscopy, in fluorescence microscopy

the sample is illuminated through the objective lens with a narrow set

of wavelengths of light. This light interacts with fluorophores in the

sample which then emit light of a longer wavelength. It is this emitted light which makes up the image.

Since the mid 20th century chemical fluorescent stains, such as DAPI which binds to DNA, have been used to label specific structures within the cell. More recent developments include immunofluorescence, which uses fluorescently labelled antibodies to recognize specific proteins within a sample, and fluorescent proteins like GFP which a live cell can express making it fluorescent.

Components

Basic optical transmission microscope elements (1990s)

All modern optical microscopes designed for viewing samples by

transmitted light share the same basic components of the light path. In

addition, the vast majority of microscopes have the same 'structural'

components (numbered below according to the image on the right):

- Eyepiece (ocular lens) (1)

- Objective turret, revolver, or revolving nose piece (to hold multiple objective lenses) (2)

- Objective lenses (3)

- Focus knobs (to move the stage)

- Coarse adjustment (4)

- Fine adjustment (5)

- Stage (to hold the specimen) (6)

- Light source (a light or a mirror) (7)

- Diaphragm and condenser (8)

- Mechanical stage (9)

Eyepiece (ocular lens)

The eyepiece,

or ocular lens, is a cylinder containing two or more lenses; its

function is to bring the image into focus for the eye. The eyepiece is

inserted into the top end of the body tube. Eyepieces are

interchangeable and many different eyepieces can be inserted with

different degrees of magnification. Typical magnification values for

eyepieces include 5×, 10× (the most common), 15× and 20×. In some high

performance microscopes, the optical configuration of the objective lens

and eyepiece are matched to give the best possible optical performance.

This occurs most commonly with apochromatic objectives.

Objective turret (revolver or revolving nose piece)

Objective

turret, revolver, or revolving nose piece is the part that holds the

set of objective lenses. It allows the user to switch between objective

lenses.

Objective

At the lower end of a typical compound optical microscope, there are one or more objective lenses

that collect light from the sample. The objective is usually in a

cylinder housing containing a glass single or multi-element compound

lens. Typically there will be around three objective lenses screwed into

a circular nose piece which may be rotated to select the required

objective lens. These arrangements are designed to be parfocal, which means that when one changes from one lens to another on a microscope, the sample stays in focus. Microscope objectives are characterized by two parameters, namely, magnification and numerical aperture. The former typically ranges from 5× to 100× while the latter ranges from 0.14 to 0.7, corresponding to focal lengths

of about 40 to 2 mm, respectively. Objective lenses with higher

magnifications normally have a higher numerical aperture and a shorter depth of field

in the resulting image. Some high performance objective lenses may

require matched eyepieces to deliver the best optical performance.

Oil immersion objective

Two Leica oil immersion microscope objective lenses: 100× (left) and 40× (right)

Some microscopes make use of oil-immersion objectives or water-immersion objectives for greater resolution at high magnification. These are used with index-matching material such as immersion oil

or water and a matched cover slip between the objective lens and the

sample. The refractive index of the index-matching material is higher

than air allowing the objective lens to have a larger numerical aperture

(greater than 1) so that the light is transmitted from the specimen to

the outer face of the objective lens with minimal refraction. Numerical

apertures as high as 1.6 can be achieved.

The larger numerical aperture allows collection of more light making

detailed observation of smaller details possible. An oil immersion lens

usually has a magnification of 40 to 100×.

Focus knobs

Adjustment

knobs move the stage up and down with separate adjustment for coarse

and fine focusing. The same controls enable the microscope to adjust to

specimens of different thickness. In older designs of microscopes, the

focus adjustment wheels move the microscope tube up or down relative to

the stand and had a fixed stage.

Frame

The whole

of the optical assembly is traditionally attached to a rigid arm, which

in turn is attached to a robust U-shaped foot to provide the necessary

rigidity. The arm angle may be adjustable to allow the viewing angle to

be adjusted.

The frame provides a mounting point for various microscope

controls. Normally this will include controls for focusing, typically a

large knurled wheel to adjust coarse focus, together with a smaller

knurled wheel to control fine focus. Other features may be lamp controls

and/or controls for adjusting the condenser.

Stage

The stage

is a platform below the objective which supports the specimen being

viewed. In the center of the stage is a hole through which light passes

to illuminate the specimen. The stage usually has arms to hold slides (rectangular glass plates with typical dimensions of 25×75 mm, on which the specimen is mounted).

At magnifications higher than 100× moving a slide by hand is not

practical. A mechanical stage, typical of medium and higher priced

microscopes, allows tiny movements of the slide via control knobs that

reposition the sample/slide as desired. If a microscope did not

originally have a mechanical stage it may be possible to add one.

All stages move up and down for focus. With a mechanical stage

slides move on two horizontal axes for positioning the specimen to

examine specimen details.

Focusing starts at lower magnification in order to center the

specimen by the user on the stage. Moving to a higher magnification

requires the stage to be moved higher vertically for re-focus at the

higher magnification and may also require slight horizontal specimen

position adjustment. Horizontal specimen position adjustments are the

reason for having a mechanical stage.

Due to the difficulty in preparing specimens and mounting them on

slides, for children it's best to begin with prepared slides that are

centered and focus easily regardless of the focus level used.

Light source

Many sources of light can be used. At its simplest, daylight is directed via a mirror. Most microscopes, however, have their own adjustable and controllable light source – often a halogen lamp, although illumination using LEDs and lasers are becoming a more common provision. Köhler illumination is often provided on more expensive instruments.

Condenser

The condenser

is a lens designed to focus light from the illumination source onto the

sample. The condenser may also include other features, such as a diaphragm and/or filters, to manage the quality and intensity of the illumination. For illumination techniques like dark field, phase contrast and differential interference contrast microscopy additional optical components must be precisely aligned in the light path.

Magnification

The actual power or magnification of a compound optical microscope is the product of the powers of the ocular (eyepiece)

and the objective lens. The maximum normal magnifications of the ocular

and objective are 10× and 100× respectively, giving a final

magnification of 1,000×.

Magnification and micrographs

When using a camera to capture a micrograph

the effective magnification of the image must take into account the

size of the image. This is independent of whether it is on a print from a

film negative or displayed digitally on a computer screen.

In the case of photographic film cameras the calculation is

simple; the final magnification is the product of: the objective lens

magnification, the camera optics magnification and the enlargement

factor of the film print relative to the negative. A typical value of

the enlargement factor is around 5× (for the case of 35 mm film and a 15 × 10 cm (6 × 4 inch) print).

In the case of digital cameras the size of the pixels in the CMOS or CCD

detector and the size of the pixels on the screen have to be known. The

enlargement factor from the detector to the pixels on screen can then

be calculated. As with a film camera the final magnification is the

product of: the objective lens magnification, the camera optics

magnification and the enlargement factor.

Operation

U.S. CBP Office of Field Operations agent checking the authenticity of a travel document at an international airport using a stereo microscope

Illumination techniques

Many techniques are available which modify the light path to generate an improved contrast image from a sample. Major techniques for generating increased contrast from the sample include cross-polarized light, dark field, phase contrast and differential interference contrast illumination. A recent technique (Sarfus) combines cross-polarized light and specific contrast-enhanced slides for the visualization of nanometric samples.

- Four examples of transilumination techniques used to generate contrast in a sample of tissue paper. 1.559 μm/pixel.

- Bright field illumination, sample contrast comes from absorbance of light in the sample.

- Cross-polarized light illumination, sample contrast comes from rotation of polarized light through the sample.

- Dark field illumination, sample contrast comes from light scattered by the sample.

- Phase contrast illumination, sample contrast comes from interference of different path lengths of light through the sample.

Other techniques

Modern

microscopes allow more than just observation of transmitted light image

of a sample; there are many techniques which can be used to extract

other kinds of data. Most of these require additional equipment in

addition to a basic compound microscope.

- Reflected light, or incident, illumination (for analysis of surface structures)

- Fluorescence microscopy, both:

- Microspectroscopy (where a UV-visible spectrophotometer is integrated with an optical microscope)

- Ultraviolet microscopy

- Near-Infrared microscopy

- Multiple transmission microscopy for contrast enhancement and aberration reduction.

- Automation (for automatic scanning of a large sample or image capture)

Applications

A 40x magnification image of cells in a medical smear test taken through an optical microscope using a wet mount technique, placing the specimen on a glass slide and mixing with a salt solution

Optical microscopy is used extensively in microelectronics,

nanophysics, biotechnology, pharmaceutic research, mineralogy and

microbiology.

Optical microscopy is used for medical diagnosis, the field being termed histopathology when dealing with tissues, or in smear tests on free cells or tissue fragments.

In industrial use, binocular microscopes are common. Aside from applications needing true depth perception, the use of dual eyepieces reduces eye strain associated with long workdays at a microscopy station. In certain applications, long-working-distance or long-focus microscopes are beneficial. An item may need to be examined behind a window, or industrial subjects may be a hazard to the objective. Such optics resemble telescopes with close-focus capabilities.

Measuring microscopes are used for precision measurement. There are two basic types.

One has a reticle graduated to allow measuring distances in the focal plane. The other (and older) type has simple crosshairs and a micrometer mechanism for moving the subject relative to the microscope.

Limitations

At very high magnifications with transmitted light, point objects are seen as fuzzy discs surrounded by diffraction rings. These are called Airy disks. The resolving power

of a microscope is taken as the ability to distinguish between two

closely spaced Airy disks (or, in other words the ability of the

microscope to reveal adjacent structural detail as distinct and

separate). It is these impacts of diffraction that limit the ability to

resolve fine details. The extent and magnitude of the diffraction

patterns are affected by both the wavelength of light (λ), the refractive materials used to manufacture the objective lens and the numerical aperture

(NA) of the objective lens. There is therefore a finite limit beyond

which it is impossible to resolve separate points in the objective

field, known as the diffraction limit. Assuming that optical aberrations in the whole optical set-up are negligible, the resolution d, can be stated as:

Usually a wavelength of 550 nm is assumed, which corresponds to green light. With air as the external medium, the highest practical NA is 0.95, and with oil, up to 1.5. In practice the lowest value of d

obtainable with conventional lenses is about 200 nm. A new type of lens

using multiple scattering of light allowed to improve the resolution to

below 100 nm.

Surpassing the resolution limit

Multiple

techniques are available for reaching resolutions higher than the

transmitted light limit described above. Holographic techniques, as

described by Courjon and Bulabois in 1979, are also capable of breaking

this resolution limit, although resolution was restricted in their

experimental analysis.

Using fluorescent samples more techniques are available. Examples include Vertico SMI, near field scanning optical microscopy which uses evanescent waves, and stimulated emission depletion. In 2005, a microscope capable of detecting a single molecule was described as a teaching tool.

Despite significant progress in the last decade, techniques for surpassing the diffraction limit remain limited and specialized.

While most techniques focus on increases in lateral resolution

there are also some techniques which aim to allow analysis of extremely

thin samples. For example, sarfus

methods place the thin sample on a contrast-enhancing surface and

thereby allows to directly visualize films as thin as 0.3 nanometers.

Structured illumination SMI

SMI (spatially modulated illumination microscopy) is a light optical process of the so-called point spread function (PSF) engineering. These are processes which modify the PSF of a microscope in a suitable manner to either increase the optical resolution, to maximize the precision of distance measurements of fluorescent objects that are small relative to the wavelength of the illuminating light, or to extract other structural parameters in the nanometer range.

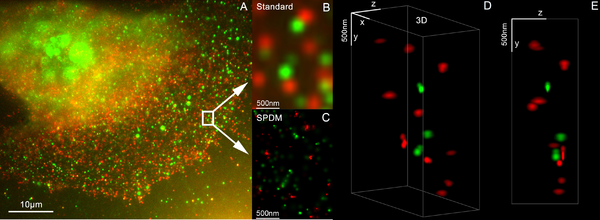

Localization microscopy SPDMphymod

3D dual color super resolution microscopy with Her2 and Her3 in breast cells, standard dyes: Alexa 488, Alexa 568 LIMON

SPDM (spectral precision distance microscopy), the basic localization microscopy technology is a light optical process of fluorescence microscopy

which allows position, distance and angle measurements on "optically

isolated" particles (e.g. molecules) well below the theoretical limit of resolution

for light microscopy. "Optically isolated" means that at a given point

in time, only a single particle/molecule within a region of a size

determined by conventional optical resolution (typically approx.

200–250 nm diameter) is being registered. This is possible when molecules within such a region all carry different spectral markers (e.g. different colors or other usable differences in the light emission of different particles).

Many standard fluorescent dyes like GFP,

Alexa dyes, Atto dyes, Cy2/Cy3 and fluorescein molecules can be used

for localization microscopy, provided certain photo-physical conditions

are present. Using this so-called SPDMphymod (physically modifiable

fluorophores) technology a single laser wavelength of suitable intensity

is sufficient for nanoimaging.

3D super resolution microscopy

3D

super resolution microscopy with standard fluorescent dyes can be

achieved by combination of localization microscopy for standard

fluorescent dyes SPDMphymod and structured illumination SMI.

STED

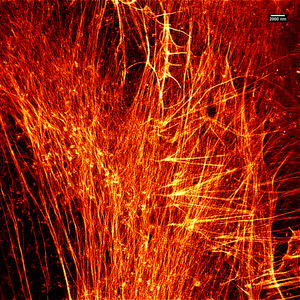

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy image of actin filaments within a cell.

Stimulated emission depletion

is a simple example of how higher resolution surpassing the diffraction

limit is possible, but it has major limitations. STED is a fluorescence

microscopy technique which uses a combination of light pulses to induce

fluorescence in a small sub-population of fluorescent molecules in a

sample. Each molecule produces a diffraction-limited spot of light in

the image, and the centre of each of these spots corresponds to the

location of the molecule. As the number of fluorescing molecules is low

the spots of light are unlikely to overlap and therefore can be placed

accurately. This process is then repeated many times to generate the

image. Stefan Hell

of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry was awarded the

10th German Future Prize in 2006 and Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2014

for his development of the STED microscope and associated methodologies.

Alternatives

In

order to overcome the limitations set by the diffraction limit of

visible light other microscopes have been designed which use other

waves.

- Atomic force microscope (AFM)

- Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

- Scanning ion-conductance microscopy (SICM)

- Scanning tunneling microscope (STM)

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

- Ultraviolet microscope

- X-ray microscope

It is important to note that higher frequency waves have limited

interaction with matter, for example soft tissues are relatively

transparent to X-rays resulting in distinct sources of contrast and

different target applications.

The use of electrons and X-rays in place of light allows much

higher resolution – the wavelength of the radiation is shorter so the

diffraction limit is lower. To make the

short-wavelength probe non-destructive, the atomic beam imaging system (atomic nanoscope) has been proposed and widely discussed in the literature, but it is not yet competitive with conventional imaging systems.

STM and AFM are scanning probe techniques using a small probe

which is scanned over the sample surface. Resolution in these cases is

limited by the size of the probe; micromachining techniques can produce

probes with tip radii of 5–10 nm.

Additionally, methods such as electron or X-ray microscopy use a

vacuum or partial vacuum, which limits their use for live and biological

samples (with the exception of an environmental scanning electron microscope).

The specimen chambers needed for all such instruments also limits

sample size, and sample manipulation is more difficult. Color cannot be

seen in images made by these methods, so some information is lost. They

are however, essential when investigating molecular or atomic effects,

such as age hardening in aluminium alloys, or the microstructure of polymers.