Climate resilience can be generally defined as the capacity for a socio-ecological system to: (1) absorb stresses and maintain function in the face of external stresses imposed upon it by climate change and (2) adapt, reorganize, and evolve into more desirable configurations that improve the sustainability of the system, leaving it better prepared for future climate change impacts.

With the rising awareness of climate change impacts by both national and international bodies, building climate resilience has become a major goal for these institutions. The key focus of climate resilience efforts is to address the vulnerability that communities, states, and countries currently have with regards to the environmental consequences of climate change. Currently, climate resilience efforts encompass social, economic, technological, and political strategies that are being implemented at all scales of society. From local community action to global treaties, addressing climate resilience is becoming a priority, although it could be argued that a significant amount of the theory has yet to be translated into practice. Despite this, there is a robust and ever-growing movement fueled by local and national bodies alike geared towards building and improving climate resilience.

With the rising awareness of climate change impacts by both national and international bodies, building climate resilience has become a major goal for these institutions. The key focus of climate resilience efforts is to address the vulnerability that communities, states, and countries currently have with regards to the environmental consequences of climate change. Currently, climate resilience efforts encompass social, economic, technological, and political strategies that are being implemented at all scales of society. From local community action to global treaties, addressing climate resilience is becoming a priority, although it could be argued that a significant amount of the theory has yet to be translated into practice. Despite this, there is a robust and ever-growing movement fueled by local and national bodies alike geared towards building and improving climate resilience.

Overview

Definition of climate resilience

In

actuality, there is still a great deal of abstract discussion and

debate regarding a number of subtle nuances associated with the precise

definition of the climate resilience perspective, such as its relation

to climate change adaptation,

the extent to which it should encompass actor-based versus

systems-based approaches to improving stability, and its relationship

with the balance of nature theory or homeostatic equilibrium view of ecological systems.

Currently, the majority of work regarding climate resilience has

been centered around examining the capacity for social-ecological

systems to sustain shocks and maintain the integrity of functional

relationships in the face of external forces. However, there is a

growing consensus in academic literature which argues that greater

attention needs to be focused on investigating the other critical aspect

of climate resilience, which is the capacity for social-ecological

systems to renew and develop, and to utilize disturbances as

opportunities for innovation and evolution of new pathways that improve

the system's ability to adapt to macroscopic changes.

Climate resilience vs. climate adaptation

The

fact that climate resilience encompasses a dual function, to absorb

shock as well as to self-renew, is the primary means by which it can be

differentiated from the concept of climate adaptation. In general, adaptation

is viewed as a group of processes and actions that help a system absorb

changes that have already occurred, or may be predicted to occur in the

future. For the specific case of environmental change and climate

adaptation, it is argued by many that adaptation should be defined

strictly as encompassing only active decision-making processes and

actions - in other words, deliberate changes made in response to climate

change.

Of course, this characterization is highly debatable: after all,

adaptation can also be used to describe natural, involuntary processes

by which organisms, populations, ecosystems

and perhaps even social-ecological systems evolve after the application

of certain external stresses. However, for the purposes of

differentiating climate adaptation and climate resilience from a

policymaking standpoint, we can contrast the active, actor-centric

notion of adaptation with resilience, which would be a more

systems-based approach to building social-ecological networks that are

inherently capable of not only absorbing change, but utilizing those

changes to develop into more efficient configurations.

Inter-connectivity between climate resilience, climate change, adaptability, and vulnerability

A graphic displaying the inter-connectivity between climate change, adaptability, vulnerability, and resilience.

A conversation about climate resilience is incomplete without also

incorporating the concepts of adaptations, vulnerability, and climate change.

If the definition of resiliency is the ability to recover from a

negative event, in this case climate change, then talking about

preparations beforehand and strategies for recovery (aka adaptations),

as well as populations that are more less capable of developing and

implementing a resiliency strategy (aka vulnerable populations) are

essential. This is framed under the assumed detrimental impacts of

climate change to ecosystems and ecosystem services.

Historical overview of climate resilience

Climate

resilience is a relatively novel concept that is still in the process

of being established by academia and policymaking institutions. However,

the theoretical basis for many of the ideas central to climate

resilience have actually existed since the 1960s. Originally an idea

defined for strictly ecological systems, resilience

was initially outlined by C.S. Holling as the capacity for ecological

systems and relationships within those systems to persist and absorb

changes to “state variables, driving variables, and parameters.” This definition helped form the foundation for the notion of ecological equilibrium:

the idea that the behavior of natural ecosystems is dictated by a

homeostatic drive towards some stable set point. Under this school of

thought (which maintained quite a dominant status during this time

period), ecosystems were perceived to respond to disturbances largely

through negative feedback

systems – if there is a change, the ecosystem would act to mitigate

that change as much as possible and attempt to return to its prior

state. However, the idea of resilience began evolving relatively quickly

in the coming years.

As greater amounts of scientific research in ecological

adaptation and natural resource management was conducted, it became

clear that oftentimes, natural systems were subjected to dynamic,

transient behaviors that changed how they reacted to significant changes

in state variables: rather than work back towards a predetermined

equilibrium, the absorbed change was harnessed to establish a new

baseline to operate under. Rather than minimizes imposed changes,

ecosystems could integrate and manage those changes, and use them fuel

the evolution of novel characteristics. This new perspective of

resilience as a concept that inherently works synergistically with

elements of uncertainty and entropy first began to facilitate changes in the field of adaptive management and environmental resources, through work whose basis was built by Holling and colleagues yet again.

By the mid 1970s, resilience began gaining momentum as an idea in anthropology, culture theory, and other social sciences.

Even more compelling is the fact that there was significant work in

these relatively non-traditional fields that helped facilitate the

evolution of the resilience perspective as a whole. Part of the reason

resilience began moving away from an equilibrium-centric view and

towards a more flexible, malleable description of social-ecological

systems was due to work such as that of Andrew Vayda and Bonnie McCay

in the field of social anthropology, where more modern versions of

resilience were deployed to challenge traditional ideals of cultural

dynamics.

Eventually by the late 1980s and early 1990s, resilience had

fundamentally changed as a theoretical framework. Not only was it now

applicable to social-ecological systems, but more importantly,

resilience now incorporated and emphasized ideas of management,

integration, and utilization of change rather than simply describing

reactions to change. Resilience was no longer just about absorbing

shocks, but also about harnessing the changes triggered by external

stresses to catalyze the evolution the social-ecological system in

question.

As the issues of global warming

and climate change have gained traction and become more prominent since

the early 1990s, the question of climate resilience has also emerged.

Considering the global implications of the impacts induced by climate

change, climate resilience has become a critical concept that scientific

institutions, policymakers, governments, and international

organizations have begun to rally around as a framework for designing

the solutions that will be needed to address the effects of global warming.

Climate resilience and environmental justice

Applications of a resilience framework: addressing vulnerability

A

climate resilience framework offers a rich plethora of contributions

that can improve our understanding of environmental processes, and

better equip governments and policymakers to develop sustainable

solutions that combat the effects of climate change. To begin with,

climate resilience establishes the idea of multi-stable socio-ecological

systems. As discussed earlier, resilience originally began as an idea

that extended from the stable equilibrium view – systems only acted to

return to their pre-existing states when exposed to a disturbance. But

with modern interpretations of resilience, it is now established that

socio-ecological systems can actually stabilize around a multitude of

possible states. Secondly, climate resilience has played a critical role

in emphasizing the importance of preventive action

when assessing the effects of climate change. Although adaptation is

always going to be a key consideration, making changes after the fact

has a limited capability to help communities and nations deal with

climate change. By working to build climate resilience, policymakers and

governments can take a more comprehensive stance that works to mitigate

the harms of global warming impacts before they happen.

Finally, a climate resilience perspective encourages greater cross-scale

connectedness of systems. Climate change scholars have argued that

solely relying on theories of adaptation is also limiting because

inherently, this perspective does not necessitate as much full-system

cohesion as a resilience perspective would. Creating mechanisms of

adaptation that occur in isolation at local, state, or national levels

may leave the overall social-ecological system vulnerable. A

resilience-based framework would require far more cross-talk, and the

creation of environmental protections that are more holistically

generated and implemented.

Vulnerability

Negative

impacts of climate change are those that are least capable of

developing robust and comprehensive climate resiliency infrastructure

and response systems. However what exactly constitutes a vulnerable

community is still open to debate.

The International Panel on Climate Change has defined vulnerability

using three characteristics: the “adaptive capacity, sensitivity, and

exposure” to the effects of climate change. The adaptive capacity

refers to a community's capacity to create resiliency infrastructure,

while the sensitivity and exposure elements are both tied to economic

and geographic elements that vary widely in differing communities. There

are, however, many commonalities between vulnerable communities.

Vulnerability can mainly be broken down into 2 major categories, economic vulnerability, based on socioeconomic factors, and geographic vulnerability. Neither are mutually exclusive.

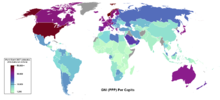

Economic vulnerability

World gross national income per capita.

At its basic level, a community that is economically vulnerable is

one that is ill-prepared for the effects of climate change because it

lacks the needed financial resources. Preparing a climate resilient

society will require huge investments in infrastructure, city planning,

engineering sustainable energy sources, and preparedness systems. From a

global perspective, it is more likely that people living at or below

poverty will be affected the most by climate change and are thus the

most vulnerable, because they will have the least amount of resource

dollars to invest in resiliency infrastructure. They will also have

the least amount of resource dollars for cleanup efforts after more

frequently occurring natural climate change related disasters.

Geographic vulnerability

A

second definition of vulnerability relates to geographic vulnerability.

The most geographically vulnerable locations to climate change are

those that will be impacted by side effects of natural hazards, such as

rising sea levels and by dramatic changes in ecosystem services,

including access to food. Island nations are usually noted as more

vulnerable but communities that rely heavily on a sustenance based

lifestyle are also at greater risk.

Abaco

Islands- An example of a low elevation island community likely to be

impacted by rising sea level associated with changing climate.

Roger E. Kasperson and Jeanne X. Kasperson of the Stockholm

Environmental Institute compiled a list of vulnerable communities as

having one or more of these characteristics.

- food insecure

- water scarce

- delicate marine ecosystem

- fish dependent

- small island community

Vulnerability and equity: environmental justice and climate justice

Equity is another essential component of vulnerability and is closely tied to issues of environmental justice and climate justice.

Who participates in and who has access to climate resiliency services

and infrastructure are more than likely going to fall along

historically unequitable patterns of distribution. As the most

vulnerable communities are likely to be the most heavily impacted, a climate justice

movement is coalescing in response. There are many aspects of climate

justice that relate to resiliency and many climate justice advocates

argue that justice should be an essential component of resiliency

strategies.

Similar frameworks that have been applied to the Climate Justice

movement can be utilized to address some of these equity issues. The

frameworks are similar to other types of justice movements and include-

contractariansim which attempts to allocate the most benefits for the

poor, utilitarianism which seeks to find the most benefits for the most

people, egalitarianism which attempts to reduce inequality, and

libertarianism which emphasizes a fair share of burden but also

individual freedoms.

The Act for Climate Justice Campaign has defined climate justice as “a vision to dissolve and alleviate the

unequal burdens created by climate change. As a form of environmental

justice, climate justice is the fair treatment of all people and freedom

from discrimination with the creation of policies and projects that

address climate change and the systems that create climate change and

perpetuate discrimination”.

Climate Justice can incorporate both grassroots as well as international and national level organizing movements.

Local level issues of equity

Many

indigenous peoples live sustenance based lifestyles, relying heavily on

local ecosystem services for their livelihoods. According to some

definitions, indigenous peoples are often some of the most vulnerable to

the impacts of climate change and advocating for participation of

marginalized groups is one goal of the indigenous people's climate

justice movement. Climate change will likely dramatically alter local

food production capacity, which will impact those people who are more

dependent on local food sources and less dependent on global or regional

food supplies. The greatest injustice is that people living this type

of lifestyle are least likely to have contributed to the causes of

global climate change in the first place. Indigenous peoples movements

often involve protests and calling on action from world leaders to

address climate change concerns.

Another local level climate justice movement is the adaptation

finance approach which has been found in some studies to be a positive

solution by providing resource dollars directly to communities in need.

International and national climate justice

The carbon market

approach is one international and national concept proposed that tries

to solve the issue by using market forces to make carbon use less

affordable, but vulnerable host communities that are the intended

beneficiaries have been found to receive little to no benefit.

One problem noted with the carbon market approach is the inherent

conflict of interest embedded between developed and sustenance based

communities. Developed nations that have often prioritized growth of

their own gross national product over implementing changes that would address climate change concerns by taxing carbon which might damage GDP.

In addition the pace of change necessary to implement a carbon market

approach is too slow to be effective at most international and national

policy levels.

Alternatively, a study by V.N Mather, et al. proposes a

multi-level approach that focuses on addressing some primary issues

concerning climate justice at local and international levels. The

approach includes:

- developing the capacity for a carbon market approach

- focusing on power dynamics within local and regional government

- managing businesses in regard to carbon practices

- special attention given to developing countries

Climate justice, environmental justice, and the United States

The issue of environmental justice and climate justice

is relevant within the United States because historically communities

of color and low socioeconomic communities have been under served and

underrepresented in terms of distribution and participation. The question of “by and for whom” resiliency strategies are targeted and implemented is of great concern. Inadequate response and resiliency strategies to recent natural disasters in communities of color, such as Hurricane Katrina, are examples of environmental injustices and inadequate resilience strategies in already vulnerable communities.

New Orleans post Hurricane Katrina levee damage.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has recently begun a Climate Justice campaign

in response to events such as Hurricane Katrina and in preparation for

future climate change related natural disasters. The goal of this

campaign is to address the 3 R's of climate justice: resilience,

resistance, and revisioning. The NAACP's climate justice initiative

will address climate resilience through advocacy, outreach, political

actions, research and education.

Climate gap

Another concept important for understanding vulnerability in the United States is the climate gap.

The climate gap is the inequitably negative impact on poor people and

people of color due to the effects of climate change. Some of these

negative impacts include higher cost of living expenses, higher

incidences of heat related health consequences in urban areas that are

likely to experience urban heat island

effects, increased pollution in urban areas, and decreases in available

jobs for poor people and people of color. Some suggested solutions to

close the climate gap include suggesting legislative policies that would

reduce the impact of climate change by reducing carbon emissions with the emphasis of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and toxic air pollution

in neighborhoods that are already heavily impacted, usually urban

centers. Other solutions include increasing access to quality health

care for poor people and people of color, preparedness planning for

urban heat island effects, identifying neighborhoods that are most

likely to be impacted, investing in alternative fuel and energy

research, and measuring the results of policy impacts.

Theoretical foundations for building climate resilience

As the threat of environmental disturbances due to climate change

becomes more and more relevant, so does the need for strategies to

build a more resilient society. As climate resiliency literature has

revealed, there are different strategies and suggestions that all work

towards the overarching goal of building and maintaining societal

resiliency.

Urban resilience

There is increasing concern on an international level with regards to addressing and combating the impending implications of climate change

for urban areas, where populations of these cities around the world are

growing disproportionately high. There is even more concern for the

rapidly growing urban centers in developing countries, where the

majority of urban inhabitants are poor or “otherwise vulnerable to

climate-related disturbances.”

Urban centers around the world house important societal and economic

sectors, so resiliency framework has been augmented to specifically

include and focus on protecting these urban systems.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC) defines resilience as “the ability of a social or ecological

system to absorb disturbances while retaining the same basic structure

and ways of functioning, the capacity of self-organization, and the

capacity to adapt to stress and change.”

One of the most important notions emphasized in urban resiliency

theory is the need for urban systems to increase their capacity to

absorb environmental disturbances. By focusing on three generalizable

elements of the resiliency movement, Tyler and Moench's urban resiliency

framework serves as a model that can be implemented for local planning

on an international scale.

The first element of urban climate resiliency focuses on

“systems’ or the physical infrastructure embedded in urban systems. A

critical concern of urban resiliency is linked to the idea of

maintaining support systems that in turn enable the networks of

provisioning and exchange for populations in urban areas.

These systems concern both physical infrastructure in the city and

ecosystems within or surrounding the urban center; while working to

provide essential services like food production, flood control, or

runoff management.

For example, city electricity, a necessity of urban life, depends on

the performance of generators, grids, and distant reservoirs. The

failure of these core systems jeopardizes human well-being in these

urban areas, with that being said, it is crucial to maintain them in the

face of impending environmental disturbances. Societies need to build

resiliency into these systems in order to achieve such a feat. Resilient

systems work to “ensure that functionality is retained and can be

re-instated through system linkages”

despite some failures or operational disturbances. Ensuring the

functionality of these important systems is achieved through instilling

and maintaining flexibility in the presence of a “safe failure.”

Resilient systems achieve flexibility by making sure that key

functions are distributed in a way that they would not all be affected

by a given event at one time, what is often referred to as spatial

diversity, and has multiple methods for meeting a given need, what is

often referred to as functional diversity.

The presence of safe failures also plays a critical role in

maintaining these systems, which work by absorbing sudden shocks that

may even exceed design thresholds.

Environmental disturbances are certainly expected to challenge the

dexterity of these systems, so the presence of safe failures almost

certainly appears to be a necessity.

Further, another important component of these systems is

bounce-back ability. In the instance where dangerous climatic events

affect these urban centers, recovering or "bouncing-back" is of great

importance. In fact, in most disaster studies, urban resilience is often

defined as "the capacity of a city to rebound from destruction." This

idea of bounce-back for urban systems is also engrained in governmental

literature of the same topic. For example, the former government's first

Intelligence and Security Coordinator of the United States described

urban resilience as "the capacity to absorb shocks and to bounce back

into functioning shape, or at the least, sufficient resilience to

prevent...system collapse." Keeping these quotations in mind,

bounce-back discourse has been and should continue to be an important

part of urban climate resiliency framework.

Other theorists have critiqued this idea of bounce-back, citing this as

privileging the status quo, rather advocating the notion of ‘bouncing

forward’, permitting system evolution and improvement.

The next element of urban climate resiliency focuses on the

social agents (also described as social actors) present in urban

centers. Many of these agents depend on the urban centers for their very

existence, so they share a common interest of working towards

protecting and maintaining their urban surroundings.

Agents in urban centers have the capacity to deliberate and rationally

make decisions, which plays an important role in climate resiliency

theory. One cannot overlook the role of local governments and community

organizations, which will be forced to make key decisions with regards

to organizing and delivering key services and plans for combating the

impending effects of climate change.

Perhaps most importantly, these social agents must increase their

capacities with regards to the notions of “resourcefulness and

responsiveness.

Responsiveness refers to the capacity of social actors and groups to

organize and re-organize, as well as the ability to anticipate and plan

for disruptive events. Resourcefulness refers to the capacity of social

actors in urban centers to mobilize varying assets and resources in

order to take action.

Urban centers will be able to better fend for themselves in the heat

of climatic disturbances when responsiveness and resourcefulness is

collectively achieved in an effective manner.

The final component of urban climate resiliency concerns the

social and political institutions present in urban environments.

Governance, the process of decision making, is a critical element

affecting climate resiliency. As climate justice has revealed, the

individual areas and countries that are least responsible for the

phenomenon of climate change are also the ones who are going to be most

negatively affected by future environmental disturbances.

The same is true in urban centers. Those who are most responsible for

climate change are going to disproportionately feel the negative effects

of climatic disturbances when compared to their poorer, more vulnerable

counterparts in society. Just like the wealthier countries have worked

to create the most pollution, the wealthier subpopulations of society

who can afford carbon-emitting luxuries like cars and homes undoubtedly

produce a much more significant carbon footprint. It is also important

to note that these more vulnerable populations, because of their

inferior social statuses, are unable to participate in the

decision-making processes with regards to these issues. Decision-making

processes must be augmented to be more participatory and inclusive,

allowing those individuals and groups most affected by environmental

disturbances to play an active role in determining how to best avoid

them.

Another important role of these social and political institutions will

concern the dissemination of public information. Individual communities

who have access to timely information with regards to hazards are

better able to respond to these threats.

Human resilience

Global

climate change is going to increase the probability of extreme weather

events and environmental disturbances around the world, needless to say,

future human populations are going to have to confront this issue.

Every society around the world differs in its capacity with regards to

combating climate change because of certain pre-existing factors such as

having the proper monetary and institutional mechanisms in place to

execute preparedness and recovery plans. Despite these differences,

communities around the world are on a level-playing field with regards

to building and maintaining at least some degree “human resilience”.

Resilience has two components: that provided by nature, and that

provided through human action and interaction. An example of climate

resilience provided by nature is the manner in which porous soil more

effectively allows for the drainage of flood water than more compact

soil. An example of human action that affects climate resilience would

be the facilitation of response and recovery procedures by social

institutions or organizations. This theory of human resilience largely

focuses on the human populations and calls for building towards the

overall goal of decreasing human vulnerability in the face of climate

change and extreme weather events. Vulnerability to climatic

disturbances has two sides: the first deals with the degree of exposure

to dangerous hazards, which one can effectively identify as

susceptibility. The second side deals with the capacity to recover from

disaster consequences, or resilience in other words.

The looming threat of environmental disturbances and extreme weather

events certainly calls for some action, and human resiliency theory

seeks to solve the issue by largely focusing on decreasing the

vulnerability of human populations.

How do human populations work to decrease their vulnerability to

impending and dangerous climatic events? Up until recently, the

international approach to environmental emergencies focused largely on

post-impact activities such as reconstruction and recovery.

However, the international approach is changing to a more

comprehensive risk assessment that includes “pre-impact disaster risk

reduction - prevention, preparedness, and mitigation.”

In the case of human resiliency, preparedness can largely be defined

as the measures taken in advance to ensure an effective response to the

impact of environmental hazards.

Mitigation, when viewed in this context, refers to the structural and

nonstructural measures undertaken to limit the adverse impacts of

climatic disturbances.

This is not to be confused to mitigation with regards to the overall

topic of climate change, which refers to reduction of carbon or

greenhouse emissions. By accounting for these impending climate

disasters both before and after the occur, human populations are able to

decrease their vulnerability to these disturbances.

A major element of building and maintaining human resilience is public health.

The institution of public health as a whole is uniquely placed at the

community level to foster human resilience to climate-related

disturbances. As an institution, public health can play an active part

in reducing human vulnerability by promoting “healthy people and healthy

homes.”)

Healthy people are less likely to suffer from disaster-related

mortality and are therefore viewed as more disaster-resilient. Healthy

homes are designed and built to maintain its structure and withstand

extreme climate events. By merely focusing on the individual health of

populations and assuring the durability of the homes that house these

populations, at least some degree human resiliency towards climate

change can be achieved.

Climate resilience in practice

The

building of climate resilience is a highly comprehensive undertaking

that involves of an eclectic array of actors and agents: individuals, community organizations, micropolitical bodies, corporations, governments at local, state, and national levels as well as international organizations.

In essence, actions that bolster climate resilience are ones that will

enhance the adaptive capacity of social, industrial, and environmental

infrastructures that can mitigate the effects of climate change.

Currently, research indicates that the strongest indicator of

successful climate resilience efforts at all scales is a well-developed,

pre-existing network of social, political, economic and financial

institutions that is already positioned to effectively take on the work

of identifying and addressing the risks posed by climate change. Cities,

states, and nations that have already developed such networks are, as

expected, to generally have far higher net incomes and GDP.

Therefore, it can be seen that embedded within the task of

building climate resilience at any scale will be the overcoming of

macroscopic socioeconomic

inequities: in many ways, truly facilitating the construction of

climate resilient communities worldwide will require national and

international agencies to address issues of global poverty, industrial development, and food justice.

However, this does not mean that actions to improve climate resilience

cannot be taken in real time at all levels, although evidence suggests

that the most climate resilient cities and nations have accumulated this

resilience through their responses to previous weather-based disasters.

Perhaps even more importantly, empirical evidence suggests that the

creation of the climate resilient structures is dependent upon an array

of social and environmental reforms that were only successfully passed

due to the presence of certain sociopolitical structures such as democracy, activist movements, and decentralization of government.

Thus it can be seen that to build climate resilience one must

work within a network of related social and economic decisions that can

have adverse effects on the success of a resilience effort given the

competing interests participating in the discussion. Given this, it is

clear that the social and economic scale play a vital role in shaping

the feasibility, costs, empirical success, and efficiency

of climate resilience initiatives. There is a wide variety of actions

that can be pursued to improve climate resilience at multiple scales –

the following subsections we will review a series of illustrative case

studies and strategies from a broad diversity of societal contexts that

are currently being implemented to strengthen climate resilience.

Local and community level

Housing and workplace conditions

Improving housing conditions in Kenya is a prime target for local climate resilience efforts

Housing inequality

is directly related to the ability for individuals and communities to

sustain adverse impacts brought on by extreme weather events that are

triggered by climate change, such as severe winds, storms, and flooding.

Especially for communities in developing nations and the Third World,

the integrity of housing structures is one of the most significant

sources of vulnerability currently.

However, even in more developed nations such as the US, there are still

multitudes of socioeconomically disadvantaged areas where outdated

housing infrastructure is estimated to provide poor climate resilience

at best, as well as numerous negative health outcomes.

Efforts to improve the resiliency of housing and workplace

buildings involves not only fortifying these buildings through use of

updated materials and foundation, but also establishing better standards

that ensure safer and health conditions for occupants. Better housing

standards are in the course of being established through calls for

sufficient space, natural lighting, provision for heating or cooling,

insulation, and ventilation. Another major issue faced more commonly by

communities in the Third World are highly disorganized and inconsistently enforced housing rights systems. In countries such as Kenya and Nicaragua, local militias

or corrupted government bodies that have reserved the right to seizure

of any housing properties as needed: the end result is the degradation

of any ability for citizens to develop climate resilient housing –

without property rights for their own homes, the people are powerless to

make changes to their housing situation without facing potentially

harmful consequences.

Grassroots community organizing and micropolitical action

Modern

climate resilience scholars have noted that contrary to conventional

beliefs, the communities that have been most effective in establishing

high levels of climate resilience have actually done so through

“bottom-up” political pressures. “Top-down” approaches involving state

or federal level decisions have empirically been marred with dysfunction

across different levels of government due to internal mismanagement and

political gridlock.

As a result, in many ways it is being found that the most efficient

responses to climate change have actually been initiated and mobilized

at local levels. Particularly compelling has been the ability of

bottom-up pressures from local civil society to fuel the creation of

micropolitical institutions that have compartmentalized the tasks

necessary for building climate resilience. For example, the city of Tokyo, Japan has developed a robust network of micropolitical agencies all dedicated to building resilience in specific industrial sectors: transportation, workplace conditions, emergency shelters, and more. Due to their compact size, local level micropolitical bodies can act

quickly without much stagnation and resistance from larger special

interests that can generate bureaucratic dysfunction at higher levels of

government.

Low-cost engineering solutions

Equally

important to building climate resilience has been the wide array of

basic technological solutions have been developed and implemented at

community levels. In developing countries such as Mozambique and Tanzania, the construction of concrete

“breaker” walls and concentrated use of sandbags in key areas such as

housing entrances and doorways has improved the ability of communities

to sustain the damages yielded by extreme weather events. Additional

strategies have included digging homemade drainage systems to protect

local infrastructure of extensive water damage and flooding.

An

aerial view of Dehli, India where urban forests are being developed to

improve the weather resistance and climate resilience of the city

In more urban areas, construction of a “green belt”

on the peripheries of cities has become increasingly common. Green

belts are being used as means of improving climate resilience – in

addition to provide natural air filtering, these belts of trees have

proven to be a healthier and sustainable means of mitigating the damages

created by heavy winds and storms.

State and national level

Climate-resilient infrastructure

Infrastructure

failures can have broad-reaching consequences extending away from the

site of the original event, and for a considerable duration after the

immediate failure. Furthermore, increasing reliance infrastructure

system interdependence, in combination with the effects of climate

change and population growth all contribute to increasing vulnerability

and exposure, and greater probability of catastrophic failures.

To reduce this vulnerability, and in recognition of limited resources

and future uncertainty about climate projections, new and existing

long-lasting infrastructure must undergo a risk-based engineering and

economic analyses to properly allocate resources and design for climate

resilience.

Incorporating climate projections into building and

infrastructure design standards, investment and appraisal criteria, and

model building codes is currently not common. Some resilience guidelines and risk-informed frameworks have been developed by public entities. For instance, the New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency,

New York City Transit Authority and Port Authority of New York and New

Jersey have each developed independent design guidelines for the

resiliency of critical infrastructure.

To address the need for consistent methodologies across

infrastructure sectors and to support development of standards for

adaptive design and risk management owing to climate change, the American Society of Civil Engineers

has published a Manual of Practice on Climate-Resilient

Infrastructure. The manual offers guidance for adaptive design methods,

characterization of extremes, development of flood design criteria,

flood load calculation and the application of adaptive risk management

principals account for more severe climate/weather extremes.

Infrastructural development disaster preparedness protocols

At larger governmental levels, general programs to improve climate resiliency through greater disaster preparedness are being implemented. For example, in cases such as Norway,

this includes the development of more sensitive and far-reaching early

warning systems for extreme weather events, creation of emergency electricity power sources, enhanced public transportation systems, and more.

To examine another case study, the state California

in the US has been pursuing more comprehensive federal financial aid

systems for communities afflicted by natural disaster, spurred in part

by the large amounts of criticism that was placed on the US federal

government after what was perceived by many to be a mishandling of Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy relief.

Additionally, a key focus of action at state and federal levels

is in improving water management infrastructure and access. Strategies

include the creation of emergency drinking water supplies, stronger sanitation technology and standards, as well as more extensive and efficient networks of water delivery.

Social services

Climate

resilience literature has also noted that one of the more indirect

sources of resilience actually lies in the strength of the social services and social safety net

that is provided for citizens by public institutions. This is an

especially critical aspect of climate resilience in more

socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, cities, and nations. It has

been empirically found that places with stronger systems of social security and pensions oftentimes have better climate resiliency. This is reasoning in the following manner: first of all, better social services for citizens translates to better access to healthcare, education, life insurance,

and emergency services. Secondly, stronger systems of social services

also generally increase the overall ownership of relevant economic

assets that are correlated with better quality of life such as savings,

house ownership, and more. Nations where residents are on more stable

economic footing are in situations where there is a far higher incentive

for private investment into climate resilience efforts.

Global level

International treaties

At

the global level, most action towards climate resilience has been

manifested in the signing of international agreements that set up

guidelines and frameworks to address the impacts of climate change.

Notable examples include the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, and the 2010 Cancun Agreement.

In some cases, as is the case with the Kyoto Protocol for example, these

international treaties involve placing legally binding requirements on

participant nations to reduce processes that contribute to global

warming such as greenhouse gas emissions.

In other cases, such as the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference

in Cancun, proposals for the creation of international funding pools to

assist developing nations in combating climate change are seen.

However, that enforcement of any of the requirements or principles that

are established in such international treaties has ambiguous: for

example, although the 2010 Cancun conference called for the creation of a

100 billion dollar “Green Climate Fund” for developing nations, if and

how this fund will actually be created still remains unclear.

Case studies

As the looming threat of climate change

and environmental disturbances becomes more and more immediate, so does

the need for policy to combat the issue. As a relatively new

phenomenon, climate change has yet to receive the political attention it

deserves. However, the climate justice and climate change

movements are gaining momentum on an international scale as both grass

roots campaigns and supranational organizations begin to gain influence.

However, the most significant and impacting changes come from national

and state governments around the world, as they have the political and

monetary power to more effectively enforce their proposals.

United States (as a country)

As

it stands today, there is no country-wide legislation with regards to

the topic of climate resiliency in the United States. However, in mid

February 2014, President Barack Obama announced his plan to propose a $1 billion “Climate Resilience Fund”.

The details of exactly what the fund will seek to accomplish are vague

since the fund is only in the stage of being proposed for Congress's

approval in 2015. However, in the speech given the day of the

announcement of this proposal, Obama claimed he will request “...new

funding for new technologies to help communities prepare for a changing

climate, set up incentives to build smarter, more resilient

infrastructure. And finally, my administration will work with tech

innovators and launch new challenges under our Climate Data Initiative,

focused initially on rising sea levels and their impact on the coasts,

but ultimately focused on how all these changes in weather patterns are

going to have an impact up and down the United States - not just on the

coast but inland as well - and how do we start preparing for that.”

Obama's fund incorporates facets of both urban resiliency and human

resiliency theories, by necessarily improving communal infrastructure

and by focusing on societal preparation to decrease the country's

vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix's large population and extremely dry climate make the city

particularly vulnerable to the threats of drought and extreme heat.

However, the city has recently incorporated climate change into current

(and future) water management and urban design. And by doing so, Phoenix

has taken steps to ensure sustainable water supplies and to protect

populations that are vulnerable to extreme heat, largely through

improving the sustainability and efficiency of communal infrastructure.

For example, Phoenix uses renewable surface water supplies and reserves

groundwater for use during the instance when extended droughts arise.

The city is also creating a task force to redesign the downtown core to

minimize the way buildings trap heat and increase local temperatures.

The

outdated infrastructure pictured here in the Phoenix downtown will be

undergoing drastic changes geared towards improvements in efficiency.

Denver, Colorado

The city of Denver

has made recent strides to combat the threat of extreme wildfires and

precipitation events. In the year 1996, a fire burned nearly 12,000

acres around Buffalo Creek,

which serves as the main source of the city's water supply. Two months

following this devastating wildfire, heavy thunderstorms caused flash

floods in the burned area, having the effect of washing sediment into

the city's reservoir. In fact, this event washed more sediment into the

reservoir than had accumulated in the 13 years prior. Water treatment

costs were estimated to be $20 million over the next decade following

the event. Denver needed a plan to make sure that the city would not be

devastated by future wildfire and flash flood events. DenverWater and

the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region are working together to

restore more than 40,000 acres of National Forests lands through processes like reforestation, erosion control, and the decommissioning of roads. Further, Denver

has installed sensors in the reservoirs in order to monitor the quality

of the water and quantity of debris or sediment. These accomplishments

will have the effect of building a more resilient Denver, Colorado

towards the impending increase of extreme weather events such as

wildfire and flooding.

China

Pictured

here is the conversion of three large rivers in Ningbo, China. The

country is taking substantial measures to combat the flash floods

predicted to intensify in the future.

China has been rapidly emerging as a new superpower, rivaling the United States.

As the most populated country in the world, and one of the leaders of

the global economy, China's response to the impending effects of climate

change is of great concern for the entire world. A number of

significant changes are expected to affect China as the looming threat

of climate change

becomes more and more imminent. Here's just one example; China has

experienced a seven-fold increase in the frequency of floods since the

1950s, rising every decade. The frequency of extreme rainfall has

increased and is predicted to continue to increase in the western and

southern parts of China. The country is currently undertaking efforts to

reduce the threat of these floods (which have the potential effect of

completely destroying vulnerable communities), largely focusing on

improving the infrastructure responsible for tracking and maintaining

adequate water levels. That being said, the country is promoting the

extension of technologies for water allocation and water-saving

mechanisms. In the country's National Climate Change Policy Program,

one of the goals specifically set out is to enhance the ability to bear

the impacts of climate change, as well as to raise the public awareness

on climate change. China's National Climate Change Policy states that

it will integrate climate change policies into the national development

strategy. In China, this national policy comes in the form of its "Five

Year Plans for Economic and Social Development". China's Five Year Plans

serve as the strategic road maps for the country's development. The

goals spelled out in the Five Year Plans are mandatory as government

officials are held responsible for meeting the targets.

India

As the world's second most populous country, India is taking action on a number of fronts in order to address poverty, natural resource management, as well as preparing for the inevitable effects of climate change.

India has made significant strides in the energy sector and the country

is now a global leader in renewable energy. In 2011 India achieved a

record $10.3 billion (USD) in clean energy investments, which the

country is now using to fund solar, wind, and hydropower projects around

the country. In 2008, India published its National Action Plan on

Climate Change (NAPCC), which contains several goals for the country.

These goals include but are not limited to: covering one third of the

country with forests and trees, increasing renewable energy supply to 6%

of total energy mix by 2022, and the further maintenance of disaster

management. All of the actions work to improve the resiliency of the

country as a whole, and this proves to be important because India has an

economy closely tied to its natural resource base and climate-sensitive

sectors such as agriculture, water, and forestry.