The good news is that the government of

Bangladesh is about to approve Golden Rice for commercial release some time in the next three months.

First and foremost this is fantastic news for Southeast Asia for

humanitarian and economic development reasons. On a less consequential

level this is great news for the overall debate surrounding the use of

biotech in agriculture. Golden Rice occupied a space in the debate as

the

Great Golden Hope of Biotech Crops, a wholly virtuous crop

devoid of the grubby commercial concerns of intellectual property or

profit motive. In this case, the IP had been donated, the rice was being

developed by a non-profit NGO and the rice will be given freely to

farmers and local breeding programs—a trait of value directly to

consumers, among them some of the most vulnerable people on the planet.

Because of this history, it is a crop not linked to so-called

‘industrial agriculture’ and its key trait is not tied to pesticide use.

Golden Rice has long been promoted as an application of biotech that

is seemingly beyond reproach, although that didn’t stop critics from

coming up with cynical and loopy objections: e.g. Golden Rice is a

stalking horse for corporate control of agriculture in Southeast Asia;

it is a distraction from solving the problems of poverty and equitable

food distribution, etc, etc. But the halo that surrounded Golden Rice

had faded considerably in recent years, as its release date, which has

been ‘just around the corner’ for the last decade and a half kept

getting pushed back into what seemed like a permanently receding future.

For the entire time that I’ve been paying close attention to the GMO

debate, beginning around 2011, Golden Rice has been both just around the

corner and long overdue, which has made it an easy target for

environmental NGO critics. Advocates often had an unfortunate way of

referring to Golden Rice in a weirdly liminal space between a pipeline

crop with theoretical benefits that would probably bear out and a

already existing commercially released crop already in production. There

has also been an unfortunate tendency to over-estimate how much the

destruction of crop trials set back the time-line and impute them with

genocidal consequences. One

2014 paper calculated “1.4

million life years lost over the past decade in India” but was

predicated on the idea that Golden Rice had been available since 2000

and was entirely held back by critics of genetic engineering, in the

form of overly precautionary regulations of field trials. This became a

trope that circulated widely in pro-GMO circles and formed the

foundation for many a hysterical charge of genocide against GMO critics,

even those who questioned the wisdom of herbicide tolerant crops who’d

registered no objection to Golden Rice. But it is not the case that

Golden Rice has been available since 2000 or that regulation rather than

formidable technical challenges have been the main bottleneck.

This

anti-biotech blog post from 2011 highlights the way appeals to the

potential of Golden Rice became less and less persuasive as the release

date seemed to perpetually recede into the future.

This

anti-biotech blog post from 2011 highlights the way appeals to the

potential of Golden Rice became less and less persuasive as the release

date seemed to perpetually recede into the future.

The most straightforward criticism from opponents became increasingly

difficult to parry over time, “If genetic engineering is so great, why

is Golden Rice taking forever to get right?” The appropriate response to

that question illustrates the quandary faced by biotech advocates, for

it is both reasonable and factually correct, but to the ears of an

opponent of biotech in agriculture, unpersuasive.

First, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) should be

applauded for setting a high bar in terms of the amount of beta-carotene

and yield required for them to seek commercial release. They apparently

have never felt pressure to release a product not up to the task at

hand simply to “get something out there”. Most outrageously, its rich

for critics to blame shortcomings of the technology for the delay when

the most extreme critics have been destroying test fields of Golden Rice

for decades, with each destruction setting researcher back a full

growing season, sometimes back years for a given cultivar/trait pairing.

But most consequentially, the main reason that Golden Rice has taken so

long is that ambitious crop breeding programs take a long time.

Consider. The world conquering Honeycrisp apple took 31 years to go from the

first crosses made in 1960 to an official test designation in 1974 by the University of Minnesota apple breeder David Bedford to the

patent

in 1988 (a patent, BTW, for a conventionally breed apple 6 years before

the first GE crop hit the market) to the commercial release in 1991. A

sweet crunchy apple is a truly wonderful thing,

but nowhere near the ambition of coaxing a cornerstone, staple crop to

express beta-carotene in its endosperm without giving up any agronomic

characteristics.

Likewise, when founder of the Land Institute,

Wes Jackson, talks about

their progress over 40 years in attempting to develop a commercially

viable perennial wheat, he is lauded in food movement circles as a sage,

and far seeing prophet:

When I first started working on this 40 years ago, I said

this is going to take 50 to 100 years. The yields are lower now, but my

bet is that in the long run perennial grains will out-yield annuals.

Remember, the annual grains we have now have been 10,000 years in the

making [since farmers first started breeding wild grains]. We’ve been at

this less than half a century. So I think we are ahead of the curve.

Yet, Golden Rice, a project that began fourteen years after Jackson’s

and is ready for full, rather than niche, commercialization, is dogged

by scorn for taking so long.

Granted,

Jackson has done a much better job of managing expectations. When he

started 40 years ago, he was up front that he was beginning a half

century project. Now it’s a century project, but who’s going to quibble

over another a half century given the current crisis of soil degradation

and erosion? Golden Rice has been perpetually just around the corner

nearly from its inception.

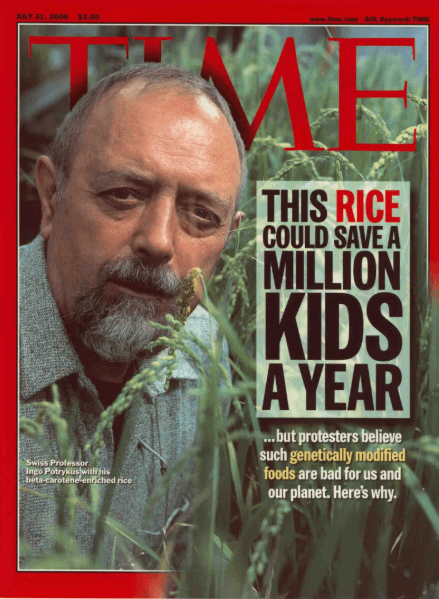

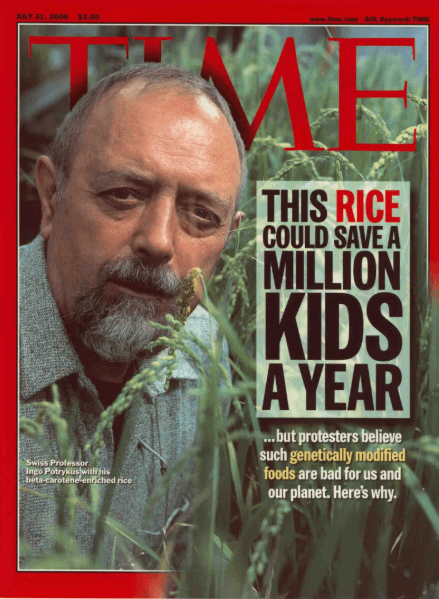

Ingo Potrykus,

the Swiss scientist who first conceived of Golden Rice, began thinking

about using genetic engineering to improve the nutrition of rice in the

1980s. In 1993 he received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to

begin work on Golden Rice. By the time he was featured on the cover of

Time Magazine in July of 2000 with the headline

“This Rice Could Save a Million Kids a Year” he and his research partner Peter Beyer had successfully introgressed genes from bacteria and daffodils into

Oryza sativa

— the most commonly consumed species of rice — and coaxed the plant

into producing beta-carotene in the endosperm. Golden Rice was presented

in the article as more or less complete in its development. That wasn’t

the case, but it certainly was the impression one got from reading the

article.

One person who apparently got that impression was organic food writer

Michael Pollan, who by March of 2001, was already braying in a New York

Times article titled “

The Great Yellow Hype”

that Golden Rice was taking too long, the rice didn’t yet deliver

enough beta-carotene, and the money invested in its development could be

better spent on other solutions. The whole thing was just an elaborate

public relations scheme for corporate biotech.

Eventually the daffodil genes were abandoned in favor of genes from maize which brought the amount of beta-carotene. By 2005,

Golden Rice 2 delivered up to 23 times the amount of beta-carotene as the daffodil gene based rice. A

2009 study

found that a cup of cooked Golden Rice delivered the equivalent of half

a days worth of required vitamin A for adults. Getting the biofortified

rice to maintain the same yield as its non-biofortified parent

continued to be a challenge, a yield gap they only recently seemed to

have closed. As recently as 2016, they were on record as still facing

yield drag. A thoughtful, well researched article in February 2016 by

environmental agriculture writer Tom Philpott of Mother Jones asked the

question,

“WTF Happened to Golden Rice?”:

On its website, the IRRI reports that in the latest field

trials, golden rice varieties “showed that beta carotene was produced

at consistently high levels in the grain, and that grain quality was

comparable to the conventional variety.” However, the website continues,

“yields of candidate lines were not consistent across locations and

seasons.” Translation: The golden rice varieties exhibited what’s known

in agronomy circles as a “yield drag”—they didn’t produce as much rice

as the non-GM varieties they’d need to compete with in farm fields. So

the IRRI researchers are going back to the drawing board.

Via email, I asked the IRRI how that effort is going. “So far, both

agronomic and laboratory data look very promising,” a spokeswoman

replied. But she declined to give a time frame for when the IRRI thinks

it will have a variety that’s ready for prime time.