Study points toward lifelong neuron formation in the human brain’s hippocampus, with implications for memory and disease

If the memory center of the human brain can grow new cells, it might help people recover from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), delay the onset of Alzheimer’s, deepen our understanding of epilepsy and offer new insights into memory and learning. If not, well then, it’s just one other way people are different from rodents and birds.

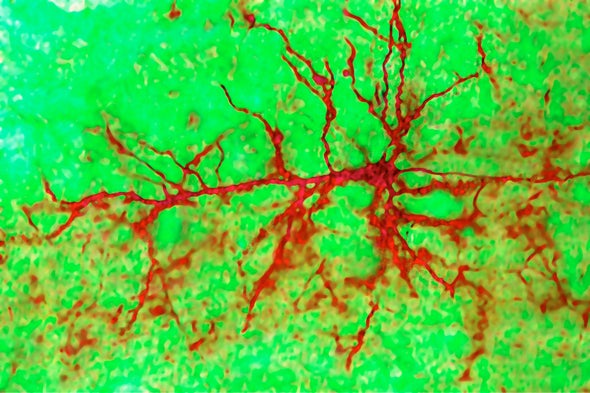

For decades, scientists have debated whether the birth of new neurons—called neurogenesis—was possible in an area of the brain that is responsible for learning, memory and mood regulation. A growing body of research suggested they could, but then a Nature paper last year raised doubts.

Now, a new study published today in another of the Nature family of journals—Nature Medicine—tips the balance back toward “yes.” In light of the new study, “I would say that there is an overwhelming case for the neurogenesis throughout life in humans,” Jonas Frisén, a professor at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, said in an e-mail. Frisén, who was not involved in the new research, wrote a News and Views about the study in the current issue of Nature Medicine.

Not everyone was convinced. Arturo Alvarez-Buylla was the senior author on last year’s Nature paper, which questioned the existence of neurogenesis. Alvarez-Buylla, a professor of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, says he still doubts that new neurons develop in the brain’s hippocampus after toddlerhood.

“I don’t think this at all settles things out,” he says. “I’ve been studying adult neurogenesis all my life. I wish I could find a place [in humans] where it does happen convincingly.”

For decades, some researchers have thought that the brain circuits of primates—including humans—would be too disrupted by the growth of substantial numbers of new neurons. Alvarez-Buylla says he thinks the scientific debate over the existence of neurogenesis should continue. “Basic knowledge is fundamental. Just knowing whether adult neurons get replaced is a fascinating basic problem,” he said.

New technologies that can locate cells in the living brain and measure the cells’ individual activity, none of which were used in the Nature Medicine study, may eventually put to rest any lingering questions.

A number of researchers praised the new study as thoughtful and carefully conducted. It’s a “technical tour de force,” and addresses the concerns raised by last year’s paper, says Michael Bonaguidi, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.

The researchers, from Spain, tested a variety of methods of preserving brain tissue from 58 newly deceased people. They found that different methods of preservation led to different conclusions about whether new neurons could develop in the adult and aging brain.

Brain tissue has to be preserved within a few hours after death, and specific chemicals used to preserve the tissue, or the proteins that identify newly developing cells will be destroyed, said Maria Llorens-Martin, the paper’s senior author. Other researchers have missed the presence of these cells, because their brain tissue was not as precisely preserved, says Llorens-Martin, a neuroscientist at the Autonomous University of Madrid in Spain.

Jenny Hsieh, a professor at the University of Texas San Antonio who was not involved in the new research, said the study provides a lesson for all scientists who rely on the generosity of brain donations. “If and when we go and look at something in human postmortem, we have to be very cautious about these technical issues.”

Rusty Gage, president of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and a neuroscientist and professor there, says he was impressed by the researchers’ attention to detail. “Methodologically, it sets the bar for future studies,” says Gage, who was not involved in the new research but was the senior author in 1998 of a paper that found the first evidence for neurogenesis. Gage says this new study addresses the concerns raised by Alvarez-Buylla’s research. “From my view, this puts to rest that one blip that occurred,” he says. “This paper in a very nice way… systematically evaluates all the issues that we all feel are very important.”

Neurogenesis in the hippocampus matters, Gage says, because evidence in animals shows that it is essential for pattern separation, “allowing an animal to distinguish between two events that are closely associated with each other.” In people, Gage says, the inability to distinguish between two similar events could explain why patients with PTSD keep reliving the same experiences, even though their circumstances have changed. Also, many deficits seen in the early stages of cognitive decline are similar to those seen in animals whose neurogenesis has been halted, he says.

In healthy animals, neurogenesis promotes resilience in stressful situations, Gage says. Mood disorders, including depression, have also been linked to neurogenesis.

Hsieh says her research on epilepsy has found that newborn neurons get miswired, disrupting brain circuits and causing seizures and potential memory loss. In rodents with epilepsy, if researchers prevent the abnormal growth of new neurons, they prevent seizures, Hsieh says, giving her hope that something similar could someday help human patients. Epilepsy increases someone’s risk of Alzheimer’s as well as depression and anxiety, she says. “So, it’s all connected somehow. We believe that the new neurons play a vital role connecting all of these pieces,” Hsieh says.

In mice and rats, researchers can stimulate the growth of new neurons by getting the rodents to exercise more or by providing them with environments that are more cognitively or socially stimulating, Llorens-Martin says. “This could not be applied to advanced stages of Alzheimer’s disease. But if we could act at earlier stages where mobility is not yet compromised,” she says, “who knows, maybe we could slow down or prevent some of the loss of plasticity [in the brain].”